36° 44' 31"N, 78° 14' 02"W (Topo map) - SOUTH HILL quad.

Submitted by June Banks Evans 8 Aug 2003

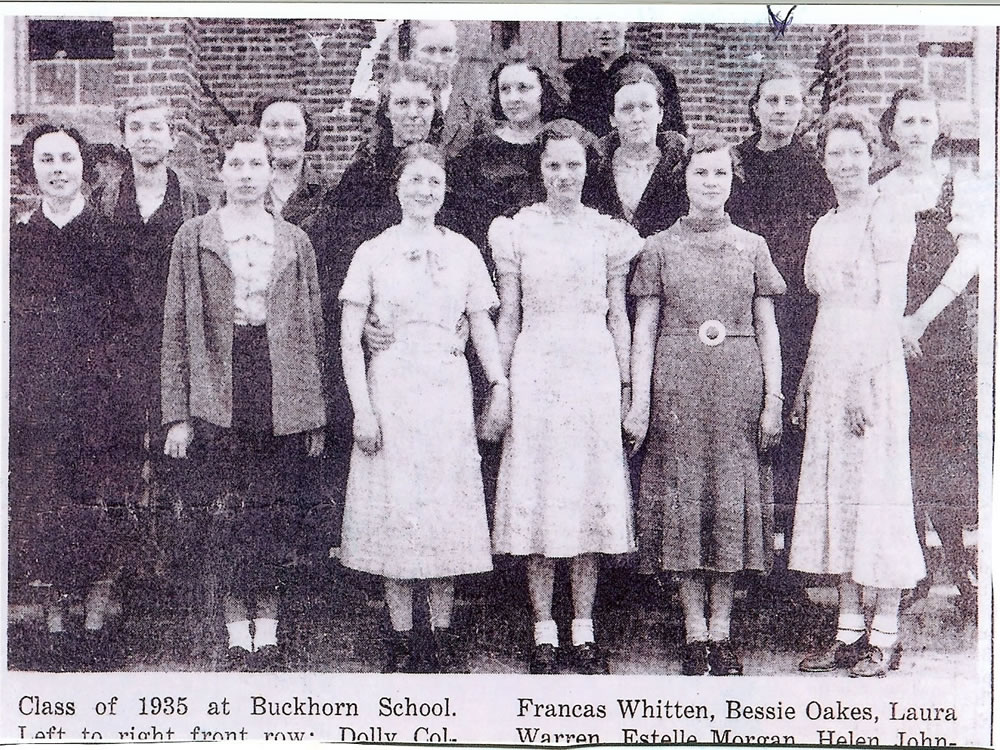

Buckhorn High School Class of 1935

Dec 2006: Thanks to Marshall Styles for contributing the photo.

Annie Lou Colley is third from the right, and has a "V"-shaped arrow marked

just over her head. Annie was born 14 January 1914, the daughter of Henry Lee Colley and Almeyda Lee Royster of

Mecklenburg County.

July 10, 2007: Thanks to Heather Chaney,

daughter-in-law of Annie Lou Colley Chaney, for these identifications:

The two young men in the background are Marvin Jordan on the left and

Ogburn Powell on the right.

Back row of the girls: Frances Whitten,

Bessie Oaks, Laura Warren, Estell Morgan, Helen Johnson, Annie Lou

Colley, Eleanor Barnes

Front row: Dolly Collins, Lilly Whitten, Helen

Newman, Gertie Creedle, Delma, Holmes, Virginia Dare Crowder

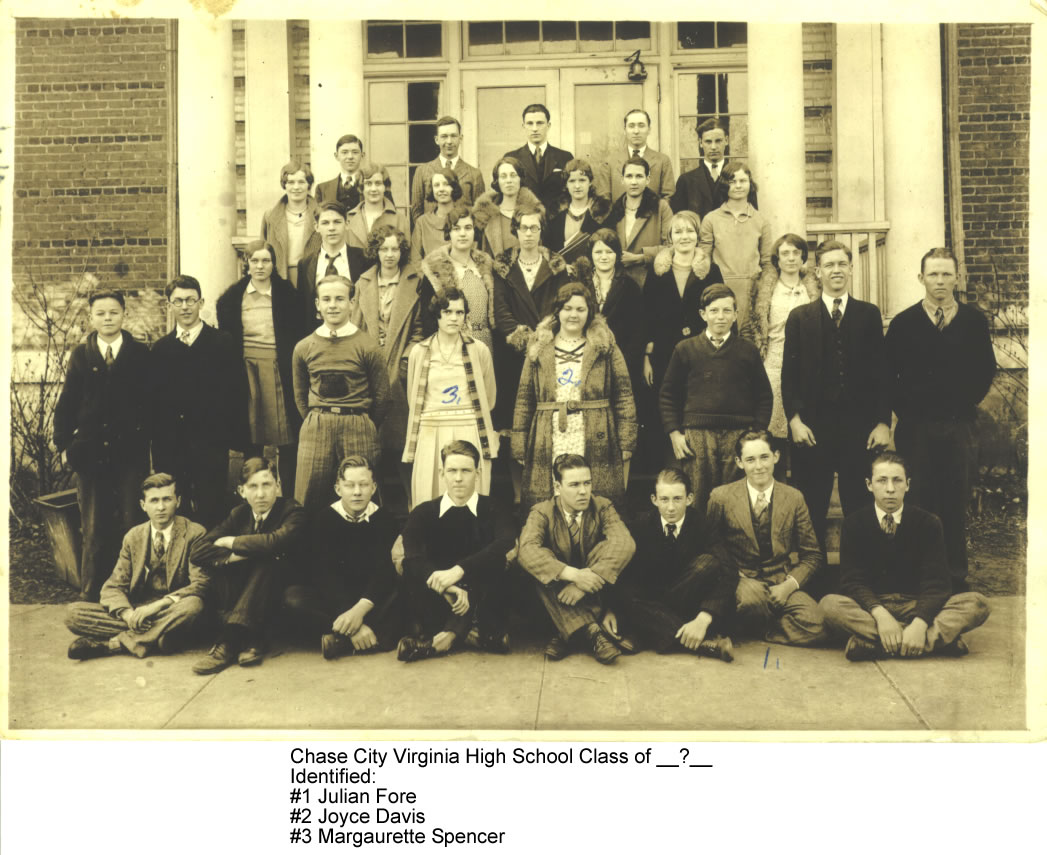

Bessie Lee GREGORY, daughter of E. J. & Ida GREGORY

Contributed by JoLee Gregory-Spears

1. Julian FORE

2. Joyce DAVIS

3. Margaurette SPENCER

Contributed by JoLee Gregory-Spears

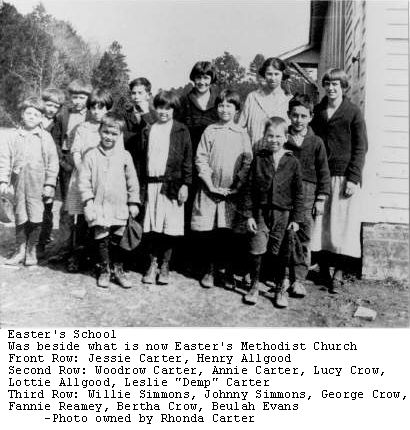

Easter's School was beside what is now Easter's Methodist Church

Front Row: Jessie CARTER, Henry ALLGOOD

Second Row: Woodrow CARTER, Annie CARTER, Lucy CROW, Lottie ALLGOOD, Leslie "Demp" CARTER

Third Row: Willie SIMMONS, Johnny SIMMONS, George CROW, Fannie REAMEY, Bertha CROW, Beulah EVANS

Contributed by Rhonda Carter

This was pointed out to me as "Finneywood School." Is this the "Freedmen School"?

Life By the Roaring Roanoke, Bracey, pp 248 & 250, refers to a school on the Burwell plantation, a one-room frame structure that replaced the old log building ... "and Isaac Craighead became the first Negro teacher in the school. Long known as the Burwell School, it was located near the village of Finneywood and near the white Finneywood Christian Church. Before closing around 1960, the school's name may have been changed to Finneywood, after the white school of that name closed in the 1930's."

We need verification to place the photo as a landmark in the Finneywood area of Mecklenburg Co., VA.

A senior person believes the white Finneywood school was near a Mock home, and not at this exact site.

Any input is very welcomed.

Contributed by JoLee Gregory Spears

Forksville School [demolished], was located at 36° 45' 24"N, 78° 03' 24"W, Route #638, Wilson Road (old U.S. Route #1, Route #31, Boydton-Petersburg Plank Road), in Mecklenburg County. This building was on 1½ acres deeded from Edmund Mitchell Hite on 01 Oct 1891 to R. J. Montgomery and others as trustees of the South Hill District. [MDB 142:196]

"Recent" photo of Booker School in Forksville

Submitted 2003 Aug 09 by June Banks Evans

Item 1:

In the article "Sesquicentennial of Methodism in Southside

Virginia," The Richmond Christian Advocate, 21 June 1934, it was noted

that in "1874 the first free school in this section was held in old

Providence Church. Jesse Q. Gee was principal and his daughter, Miss

Alice, assistant."

Item 2:

Quoting from The Journals of

William Emmanuel Bugg, 1848-1935, transcribed by June Banks Evans, New

Orleans: Bryn Ffyliaid Publications, 1986, with additional material on

lines Bugg, Davis, Hudgins Nicholson, Smith, and Walker:

[page 7]

Preface: Written Forksville, Virginia, March 28, 1928 The first school I

ever went to was taught by Miss Bettie Nash in 1857 and 1858, near the

Union Mills on the Meherrin River three quarters of a mile south of the

Harper place. The schoolhouse was built of pine poles or logs and had

only a dirt floor. Its stick and dirt chimney had a fireplace, five or

six feet wide, covered with three-foot riven pine boards.

Every

Monday morning I went on horseback from the old Hundley Hudgins place,

where I lived with my grandmother Ann Harper Hudgins, to her brother

Davie (David) Harper’s place, where I boarded from Monday to Friday with

my great-grandmother Harper. Mr. Billie (William K.) Nash attended to

Davie Harper’s business as overseer. Armistead, a Colored boy, always

went with me, to carry the horse back, and on Friday he would bring me

the horse so I could return home. I loved him very much.

During

the third year of my schooling, when my grandmother died, I went to

school in the old South-Hill Methodist Episcopal Church, near the

Benjamin (Jenkins) Smith place, which was then occupied by Wesley

McAdden. The teacher was William A. Wilder, a Yankee from Petersburg,

Virginia.

In 1860 and part of 1861 my teacher at the South-Hill

school was James A. Riddick, but in June he closed the school and

enlisted in the Confederate War between the States, which lasted four

years, 1861 to 1865. For the remainder of 1861 and 1862 I went to school

in North Carolina, to my Uncle Aaron’s wife, Mrs. Caroline [Williams]

Hudgins, who only taught her sister, Miss Pattie Williams, and myself.

The next year, 1863, I went to school to the widow Mrs. Sarah

Moseley Jeter, a daughter of E. J. Moseley, deceased. She taught at

South-Hill in the old Wilson place and in a house in the yard, later

called the Loveland place.

In 1864 I went to school in the old

Providence Methodist Episcopal Church. My teacher was Mr. James

Northington, who lived at Forksville. The next year I went to school

near Forksville to Virginius Q. Gee at the house of his father J. Q.

Gee. In 1866 and 1867 I went to school to Mr. Jesse Q. Gee at his house,

Safe Retreat, and this was the last of my going to school, except for

the four or five months in 1874 when I went to Maj. W. C. Drake in

Oakville, North Carolina, for a review of studies in order to teach.

Submitted by June Banks Evans

Margaret Elizabeth Campbell, Matron, 1903 - 1908

Margaret Elizabeth Campbell was appointed as Matron

at Thyne Institute in Chase City, Virginia on July 6, 1903 at the annual meeting

of the United Presbyterian Church of North America Board of Missions to the

Freedmen in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania (United Presbyterian Church of North

America, 1904, p.172-173). She was reappointed for 9 months each year 1904-1907

at a salary of $50 per month (United Presbyterian Church of North America, 1911,

pp. 49-50, 84-86). After her appointment on July 2, 1907, there is no further

record of her service (United Presbyterian Church of North America, 1911,

p.122).

Her duties included responsibility for the dormitories for the

boarding students, Vincent Hall with 18 to 28 girls and Hunter Hall with 20 to

21 boys. She also had responsibility for the dining room in Vincent Hall and for

many of the evening and weekend activities. She conducted the Literary Society

on Saturday evening and Prayer Meeting on Sabbath evening and took the students

to chapel on Sabbath afternoon for sermon and Sabbath school. On the last

Tuesday of each month, she took them to the Temperance League, on first Friday

to Farmer's Conference, and weekly she assisted with the boys' Debating Society

(Campbell, 1906; Campbell, 1907).

In the Report of the Secretary of the

Freedmen's Missions for the year ending April 15, 1906 published in the Women's

General Mission Society Magazine, the secretary reports:

"At Chase City,

Va., Miss M. E. Campbell has care of Vincent Hall with 18 girls and Hunter Hall

with 20 boys, and has proved a careful manager. All dine together in Vincent

Hall dining room, and here, too, they hold their literary society on Saturday

evening, and prayer meeting every Sabbath evening, under the care of the

matron." (p.539)

In her 1905 report, Campbell reports that, in

addition to their regular school work, domestic science, and sewing, the girls

were instructed in "cooking, dish-washing, baking, sweeping, bed-making, and all

of the duties pertaining to housekeeping" (Campbell, 1905, p. 444). She also

describes the work of the Literary Society. "After singing and prayer, roll is

called, and each member is expected to answer to his name by reporting any

incorrect use of language he has heard by other members of the society during

the week and any irreverent conduct during religious services" (Campbell, 1905,

p. 444). She also notes that she conducted Family Worship each morning and, in

the evening, she called on someone to volunteer in prayer. Her report concludes,

"We feel that God is blessing the work in this part of His vineyard" (Campbell,

1905, p. 444).

Another of her duties must have been to raise money and

donations for the school. Her reports always included thanks to the Women's

Missionary Society at various churches, including Ninth Avenue United

Presbyterian in Monmouth, Illinois for gifts. She also acknowledged gifts given

in memory of women, including her older sister, Elizabeth A. Campbell Henderson,

who died in 1905. Among the items mentioned are carpet, pillowcases, sheets,

towels, and tables purchased with a $25 donation (Campbell, 1906, p. 542). Books

and clothing were frequently requested as well. When she returned to Monmouth in

the summers, Margaret gave talks at churches to help raise money and solicit

donations of clothes and books.

In her report for 1906-1907, Matron

Campbell tells about a fire that occurred in the girls' dormitory on the night

of January 28th. She reports:

"The fire threw 23 girls and one teacher

out of a home and deprived 20 boys of a dining room. The boys very

good-naturedly vacated the second floor of Hunter Hall, which was converted into

a girls' dormitory, the boys being content with very cramped quarters on the

first floor. The building is so constructed that the two dormitories are

entirely separate. We utilized the old laundry as kitchen and dining room,

serving breakfast there the morning after the fire. The boys and some of the

girls worked nobly to save the building. The spirit shown by Miss Annie Wilson

was especially praiseworthy, unselfishly fighting the flames, with no thought of

saving her own belongings. In it all, we feel very grateful to our Heavenly

Father that He spared the lives of all the students, the matron and the nine

teachers who were in the building, and, notwithstanding the severe cold, the

ground covered with snow, and most of them poorly clad, having lost much of

their wearing apparel, no sickness followed." (Campbell, 1907, p. 470).

Margaret Elizabeth Campbell was born in West Newton

(Westmoreland County southeast of Pittsburgh), Pennsylvania on November 7, 1846

the sixth of 10 children of Mungo Dick Campbell and Maryann L. Mabon Campbell.

In 1856, the family went by boat to Burlington, Iowa and settled in Monmouth,

Illinois where Mungo Dick Campbell ran a grain elevator and coal business. The

family lived at 513 South 4th Street in Monmouth and were active members of the

United Presbyterian Church, initially the Second Church and later the Ninth

Avenue Church. Margaret, as well as her brothers James and Robert, attended

Monmouth College in the 1860s. The College had been founded in 1856 by the

United Presbyterian Church as a liberal arts college with a firm religious base

(Nurss, 1993, pp. 4-5).

In 1903, Margaret was President of the Women's

Missionary Society at Ninth Avenue United Presbyterian Church. She also was a

delegate to the Women's General Missionary Society 20th Annual Convention held

in Allegheny, Pennsylvania on May 12-15, 1903. She was nearly 57 years old when

she went to Virginia to work at Thyne Institute.

[Editor's note: My

assumption is that, as the only unmarried daughter in the family, she stayed at

home to care for her parents until they died in 1894-her mother in August at age

78 and her father in October at age 85.]

In considering Margaret's

motivation for going to Thyne Institute, it is interesting to speculate on the

influence her older brother, Robert M. Campbell, may have had on her decision to

work with Black children. She had been an active correspondent with him when he

served in the Union Army during the Civil War, including the period when he was

a Captain in charge of a regiment of "Colored" soldiers after Emancipation. He

had frequently written to Maggie about attending the black soldiers' prayer

meetings and especially enjoyed their singing. He also had been involved in

setting up a school for the men in camp whenever possible to teach them to read

and write. He hired teachers and requested Maggie to send spelling books for his

school (Nurss, 1993, pp. 45-46). Robert had enlisted in the army for patriotic

reasons with peer pressure and excitement as added factors (Nurss, 1993, p. 8).

Her joined the black regiment "because he felt it was his duty and

responsibility to do so for both his country and for the men he would be

leading...[and] because it meant a promotion to the rank of captain which

resulted in higher pay, greater responsibility, and greater prestige" (Nurss,

1993, p. 42). His later diaries do not mention "his attitude toward racial

equality or his men's role in the war effort" (Nurss, 1993, p. 120).

For

Margaret, it appears that religious reasons were the primary motivation for her

work at Thyne Institute. She, and the wider church, clearly saw her role as a

missionary. She writes that the greatest factor upon which the success of work

with the Junior Missionary Society depends is:

"the work of the Holy

Spirit...We may have bright boys and girls in our society; we may have rooms

suitably arranged for our meetings; we may have maps, blackboards and other

desirable equipments; we may have money at our command for books, magazines and

other needed supplies; we may have time for studying new methods, preparing the

lessons and visiting the children in their homes, and yet we may fail. These

things are all very important but unless we have received from God His first and

greatest gift, His Holy Spirit, and are willing to be led by Him, it will be of

no avail" (Campbell, 1905, p. 140).

Following her five years at Thyne

Institute, Margaret Campbell returned to Monmouth where she died October

14,1936, three weeks short of her 90th birthday.

The United Presbyterian Church of North America, through its Board of Missions

to the Freedmen, established Knoxville College and 16 other schools in

Tennessee, Alabama, Virginia, and North Carolina. The Board had been established

by the General Assembly in 1863 and the first school was organized in Nashville,

Tennessee that same year. Several of the early missions, for one reason or

another, had to be closed. In 1876 a normal school, Knoxville College, was

opened in Tennessee. Also in 1876, Thyne Institute was opened in Chase City,

Virginia to provide education and spiritual and moral training to Negro

children. Summarizing the work of the Freedmen's Missions, Witherspoon (1910)

quotes a report to the board:

"The problem of the Negro is one that is

discussed on every hand, and his place in the social, industrial, and political

scale, especially, is more and more receiving the attention of thoughtful people

throughout the land. Unfortunately, a great many whose intentions are good, and

who have at heart the desire to uplift this race, are directing their efforts

along lines that ignore the necessity of moral and spiritual foundations"

(Witherspoon, p. 216).

The Rev. J. Y. Ashenhurst of Chase City, Virginia

petitioned the General Assembly of the United Presbyterian Church of North

America in 1876 indicating that there was a great need for a mission to the

Freedmen in the area. Mr. John Thyne offered 5 acres of land with his home for

use as a school. In the first year there were 73 students enrolled with an

average daily attendance of 40. A Sabbath School was also organized with 78

students enrolled. Mr. Thyne also offered to build a school on the property with

materials provided by the church as "a good, comfortable home for missionaries"

(United Presbyterian Church of North America, 1878, pp. 475-476). The following

year the work was disrupted by opposition from a "colored" Baptist preacher who

sought to be employed at the mission. The work continued, however, with the

"prudent and careful" work of the missionary, Mr. J. J. Ashenhurst, and with the

"help of the Lord" (United Presbyterian Church of North America, 1878, p.613).

Thyne Institute was the only high school for Negroes in Mecklenburg County,

Virginia. The first building built on the property was a two-story building with

a chapel and three classrooms. The Rev. John A. Ramsey was director from

1881-1883, followed by the Rev. J. H. Veasey who served until 1893. During that

time the school added a normal department (teacher training) and a primary

training school, emphasized industrial work, and built a "Girls' Industrial

Home" to house girls from long distances. The initial building (originally the

Thyne's home) was destroyed by fire in 1883. "The building was insured and was

soon replaced by another better adapted to the needs of the work" (McGranahan,

1904, p. 65). The Rev. J. M. Moore, Ph.D., became director in 1893 (Parker,

1977). The school continued to grow under his leadership, enrolling 335 in the

Sabbath School and 332 in the day school with a monthly average attendance of

185 in 1903 (Board of Freedmen's Mission, 1904, p. 36). In 1904-5, the school

year was severely interrupted by smallpox. The school was closed to day students

for two months and, when it reopened, many of the students were afraid to

return.

By 1913, the school had an enrollment of 262 with 76 boarding

students. For the first time the boys dormitory was full. The instruction

continued to emphasize industrial work, agriculture, and domestic science. There

were seven graduates all of whom were expected to teach or to take "some higher

course." The school was recognized by the State Board of Education and the

graduates were granted High School Certificates. There was a need for more

qualified teachers, leading to the formation of a Normal School held on the

premises during the summer for Thyne Institute teachers as well as teachers from

elsewhere in the state (Board of Freedmen's Missions, 1913, pp. 16-17).

Thyne Institute continued its work for the education of the Negro youth and for

the moral and spiritual uplifting of the entire community until 1946.

Mecklenburg County purchased the property and took over full support of the

school running it as a public high school for black students (Stewart, 1950).

When the local public schools were integrated in 1969, the school became the

Chase City Primary School (Kindergarten-grade 3) (Bracey, 1977, p. 251). In the

mid-80's the original Thyne Institute buildings were replaced by a new Chase

City Elementary School (Kindergarten - grade 5) continuing education on the same

land donated by John Thyne.

The Mission to the Freedmen

by the United Presbyterian Church of North America established Thyne Institute,

and its other schools as well, for the purpose of providing for the spiritual

and moral welfare of Negro children. The goal was to provide general education

of a very pragmatic sort--to prepare teachers and to teach specific skills such

as industrial work, agriculture, domestic science, sewing, and general

housekeeping. This approach to education fit well with the model proposed by

Booker T. Washington of Tuskegee Normal and Industrial Institute in Alabama.

Washington was praised by Andrew Carnegie as "the modern Moses who leads his

race and lifts it through education to even better and higher things." United

Presbyterians were encouraged to support the work of the Freedmen's Mission

noting the success of Negroes such as Booker T. Washington, Paul Lawrence

Dunbar, Frederick Douglass, Henry Ossian Tanner, Granville T. Woods, and Elijah

T. McCoy, all educated and successful Negroes of the time (Women's General

Missionary Society, 1905, pp. 40-43).

Margaret Campbell appears to have

felt called to participate in the work of the United Presbyterian

Church's Freedmen's Mission, to develop the spiritual and moral

character of the students as well as to teach homemaking skills and

provide religious instruction.

Board of Freedman's Mission. (1904). Report of Secretary

of Freedmen's Missions. Women's General Missionary Society, Board of Freedmen's

Mission Report, United Presbyterian Church of North America,1903-1905, vol. 18,

# 12, p. 36.

Board of Freedman's Mission. (1906). Report of Secretary of

Freedmen's Missions for the Year Ending April 15, 1906. In Women's General

Missionary Society, Board of Freedmen's Mission Report, United Presbyterian

Church of North America,1905-1906, vol. 19, # 12, pp. 538-542.

Board of

Freedmen's Missions of the United Presbyterian Church of North America. (1913).

Our Southland Missions. Pittsburgh, PA: United Presbyterian Church of North

America.

Bracey, Susan L. (1977). Life by the Roaring Roanoke.

Clarksville, VA: Prestwould Foundation.

Campbell, Margaret E. (1905).

Thyne Institute. Girls' Industrial Home. In Women's General Missionary Society,

United Presbyterian Church of North America, vol. 18, # 12, p. 444.

Campbell, Margaret E. (1906). Thyne Institute. Vincent Hall. In Women's General

Missionary Society, United Presbyterian Church of North America,1905-1906, vol.

19, # 12, p. 542.

Campbell, Margaret E. (1907). Thyne Institute. Vincent

Hall. In Women's General Missionary Society, United Presbyterian Church of North

America,1906-1907, vol. 20, # 12, pp. 470-471.

McGranahan, Ralph W., Ed.

(1904). Historical Sketch of the Freedmen's Mission of the United Presbyterian

Church in North America, 1862-1904. Knoxville, TN: Knoxville College.

Nurss, Kristin L. (1993). Robert M. Campbell: Civil War Diaries. Unpublished

graduate research paper. Cooperstown, NY: State University of New York at

Cooperstown.

Parker, Inez M. (1977). Rise & Decline of the Program of

Education for Black Presbyterians of the United Presbyterian Church U. S. A.,

1965-1970. San Antonio, TX: Trinity University Press.

Stewart, Archibald

K. (1950). May We Introduce... Negro Missions. Pittsburgh, PA: The Board of

American Missions, United Presbyterian Church of North America.

United

Presbyterian Church of North America. (1878). Minutes of the General Assembly of

the United Presbyterian Church of North America, 1874-1878, vol. 4. Pittsburgh:

United Presbyterian Board of Publications.

United Presbyterian Church of

North America. Board of Missions to the Freedmen. (1904). Minutes, 1894-1904,

vol. 3, pp. 174-175.

United Presbyterian Church of North America. Board

of Missions to the Freedmen. (1911). Minutes, 1904-1911, vol. 4, pp. 49-50,

84-86, 122.

Witherspoon, J. W. (1910). The Christian Education of the

Negro. In Hartshorn, W. N., Ed. & Penniman, George W., Assoc. Ed. (1910). An Era

of Progress & Promise: 1863-1910. The Religious, Moral, & Educational

Development of the American Negro Since His Emancipation. Pp. 215-216 + 227.

Boston, MA: The Priscilla Publishing Co.

Women's General Missionary

Society (1905). A Plea for the Negro. Women's General Missionary Society, United

Presbyterian Church of North America, vol. 18, pp. 40-43

Submitted 1999 June by Joanne Nurss, great-great niece of Margaret Campbell, Decatur, Georgia

Copyright © 1996 - The USGenWeb® Project, VAGenWeb, Mecklenburg County