CHAPTER I II III IV V VI VII VIII IX X XI XII XIII XIV XV XVI XVII XVIII XIX XX XXI ]

CHAPTER IX.

THE "WESTMINSTER MASSACRE."

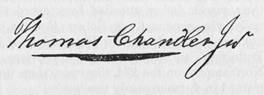

An Ante-Revolution Event — Westminster — The "Street" — The Old Meeting-house — The Pulpit — The Sounding-board — The Powder-hole — The Whips — The Collection-box — The Choir — The Foot-stove — The Burying-ground — The Grave of William French — The Epitaph — Condition of the Colonies before the Revolution — The Feeling in Cumberland County — Distrust of the Courts — Remonstrance with Judge Chandler — The Whigs assemble at Westminster — Scenes of the Night of March 13th — Norton's Tavern — The Sheriff's Posse — The Attempt to enter the Court-house — The "Massacre" — The Frolic — The Statement of Facts — Couriers — The Gathering — Appearance of the Court-house — Inhuman Suggestions — Excitement of the Yeomanry — Robert Cockran — Treatment of the Tories — Sketches of the Liberty-men — William French — His Character — Reminiscences concerning him — His Death — The Inquest — The Burial — Daniel Houghton — Jonathan Knight — Philip Safford — Tory Depositions — Weapons of the Whigs — Incidents connected with the "Massacre" — Joseph Temple — John Hooker — John Arms, the Poet — The "Massacre" in Rhyme — Thomas Chandler, Jr. — The Punishment of the Court Officers — Their Imprisonment — Their Release — Action of the Legislature of New York — Lieutenant-Governor Colden's Message — Appropriation of £1,000 — Colden to Lord Dartmouth — The Influence of Massachusetts Bay in producing the "Massacre" — What justifies an Insurrection? — Claims of William French to the title of the Proto-martyr of the Revolution.

AMONG the important events immediately preceding and connected with the war of the Revolution, which served to show the feelings of the great mass of the American people, and prognosticated the impending struggle, none has been buried in deeper obscurity than that which occurred at Westminster, on the night of the 13th of March, 1775. In some minds, the words "Westminster Massacre" may perchance awaken recollections of the venerable grandsire, who, with his descendants gathered around him,

"Wept o'er his wounds, and tales of sorrow done,

Shouldered his crutch, and showed how fields were won;"

210 HISTORY OF EASTERN VERMONT. [1775.

or who, during the long winter evenings, was wont to depict, in his own expressive language, to the listening group, the scenes of the battles of Bennington or Saratoga, or, it may be, those of the night to which allusion has been made. The descendants of a revolutionary ancestry who have been thus favored, will not forget the glow which burned on the countenance of the old patriot, nor the enthusiasm with which he referred to these and similar events, as the greatest eras in his own life and in the history of his country. To the minds of others, these words may convey but little meaning beyond their etymological signification.

When we consider the hardy character of the early settlers on the western banks of the Connecticut, their uncompromising hatred of oppression, and their holy love of freedom — which principles, originating in Massachusetts and Connecticut, had, among the hills of the adopted province, attained their full strength and reached their complete proportions — when we reflect on these considerations, we need look no further for the cause which obtained for Vermont the honor — though late accorded, yet none the less real on that account — of being the State which gave to the American States the proto-martyrs of American independence.

The most casual observer, as he passes through the towns in the south-eastern part of Vermont that border the shores of the Connecticut, cannot but notice the picturesque beauty which distinguishes, in so marked a degree, the location of Westminster. The east village; to which particular reference is made, stands principally on an, elevated plain, nearly a mile in extent, divided by a broad and beautiful avenue, along whose sides are built the comfortable and commodious dwellings of the inhabitants, back of which to the hills on the one side, and the river on the other, extend rich farms and fertile meadows. Seldom is there any noise on the "Street" at Westminster. It does not resemble Broadway, nor does it find its representative on State street at Boston. The schoolboy, it is true, shouts at noon-time and even-tide, and the shrill whistle of the engine screams through the neighboring valley, a reminder of the whoop of earlier days. But these appertain to almost every place, and tell of the universality of steam and the schoolmaster.

Of those objects in this quiet village which would most naturally attract the attention of an admirer of the infant civilization of the past century, none is more prominent than

1775.] THE OLD MEETING-HOUSE. 211

the old meeting-house. This building was commenced in 1769, and was completed in the year following. The superintendence of the work was given to a man named Brown, who dwelt at Westmoreland, New Hampshire, and who fulfilled his contract to the satisfaction of his employers. The church was formerly placed, as was the custom of the times, in the middle of the high road, but it was afterwards removed, and now stands on the line of the street. For many years the people of the village, united in faith and doctrine, were accustomed to assemble within its walls, for the purpose of worshipping in conformity with the usages of the New England Congregationalists,* but when, in the lapse of time, some of the people had embraced an oppugnant belief, vexatious disputes arose as to which of the two denominations should have possession of the building. In the end, a new edifice was erected by the Congregationalists, and their opponents, after retaining possession of the original structure for a few years, left it tenantless. Thus it remained for years undisturbed, except on town-meeting and election-days, and by the occasional visits of the peering antiquarian, the summer loiterer, or the leisurely-going traveller.

* The first minister settled in Westminster, is said to have been a man by the name of Goodell, and the year 1766 or 1767 is generally regarded as the time of his coming. Tradition affirms, that his wife was the daughter of a man distinguished in the annals of New Hampshire. In the year 1769 his faithlessness to her became known, and this discovery was soon after followed by his secret departure from the town. Mrs. Goodell's brothers, on being informed of these circumstances, took her and her two children to their home in New Hampshire, and made provision for their future support. It is not known who first occupied the pulpit of the "old meeting-house." Mice — those lovers and digesters of literature of every kind, sacred and profane — have destroyed the early records of the church, and the memory of the oldest inhabitant is at fault to supply the blank thus occasioned. The division in the church at Westminster is, with a few modifications, the history of almost all the religious societies in New England The causes which led to the formation of Christian unions were identical, with a few exceptions, in all, and the same is also true of the causes which in the end created dissensions and division.

212 HISTORY OF EASTERN VERMONT. [1775.

Although lately used for educational purposes, it still stands a model of its kind, a monument of former days. Its architecture is simple, and the soundness of its timbers bears witness to the excellence of the materials which were used in its construction. Within, all is strange to the eye of a modern. The minister's desk, placed directly in front of the huge bow-window, is overshadowed by the umbrella-like sounding-board, from which, in former days, words of wisdom and truth were often reverberated. Our ancestors were a frugal people. They regarded the air, not as an element in which to waste words, but as a medium by which ideas were to be conveyed and in order that nothing, especially of a sacred character, should be lost, they fell upon this contrivance, designed to give to the hearer the full benefit of all that the preacher might choose to utter. As one stands beneath this impending projection, a stifling sensation will steal over the senses, and a ludicrous dread lest its massiveness may descend and crush him as he gazes, is not entirely absent from. the mind. One might also feel like comparing it in situation, with the sword of Damocles. But otherwise, the comparison fails, for the hair which holds it is a bar of iron, and the structure itself bears a striking resemblance to a stemless toadstool. Modern theologians might find in it a personification of the cloud which in ancient times overhung the mercy-seat, and this, perhaps, is the most orthodox view in which it can be regarded.

Underneath the pulpit is a small apartment, in which the powder and lead belonging to the village were usually stored. Who can describe the feelings which now and then must have shot across the mind of the preacher, or imagine the nature of his secret thoughts, as Sunday after Sunday he warned his hearers of the dangers of this world and besought them to seek for safety in the next, while latent death lay barrelled beneath his feet? Immediately in front of and below the desk, are arranged the benches where once sat the deacons. Beside them, stood long whips, with which they were wont to drive from the temple the farmers' dogs which would sometimes intrude during the protracted service. Terrible instruments were these long whips to the little boys, and the least wriggle of their utmost tip, although caused by the breathing of some kind-natured zephyr, was more potent to them than the most pointed denunciations winged with fire and sulphur, and impelled by the breath of "brazen lungs." Above the deacons'

1775.] THE CHOIR. 213

seats, on a couple of nails, rested a pole, at the end of which was attached a silken pouch. This was the collection-box, which, like the spear of Ithuriel, brought forth from those whom it touched, solid, though not always willing confessions, to the cause of truth.

If there were any exercises of the sanctuary, which more than others received attention, it was those which were under the care of the village choir. There sat the young men clad in homespun and the young women gay in ribbons, occupying the whole front of the long gallery, and at the announcement of the hymn, the confusion into which they would be thrown, might have appeared to a stranger to be almost inextricable. The loud voice of the choragus proclaiming the page on which the tune was to be found in the selection "adapted to Congregational Worship by Andrew Law, A.B.," the preparatory scraping of the fiddle with a "heavenly squeak," or the premonitory key-note of the flute as it went

"——— cantering through the minor keys,"

always afforded infinite amusement to the young children, and were regarded by the old men as necessary evils, to be endured patiently and without complaint. Then would succeed a moment of silence, to be broken by the discordant harmony of ear-piercing falsettos, belching bassos, and airs, by no means as gentle as those which float

" ——— from Araby the blest."

But the music was inspiriting, if not to the listeners, yet to the performers; and when the excited fiddler, who was also the leader, became wholly penetrated with the melodies which his vocal followers were exhaling, regardless of the injunction of the minister to "omit the last stanza in singing," he would, with an extra shake of his bow and a resonant, Young America "put her through," conclude the hymn as the poet intended it should end, winding up with a grand flourish, the intensity of which was sure to excite, even in the breasts of the "oldest fogies," the most ecstatic fervor.

For years, every old lady used regularly to bring her footstove to meeting, and the warmth of her feet was of great service, no doubt, in increasing the warmth of her heart. But

214 HISTORY OF EASTERN VERMONT. [1775.

when a new-fashioned, square-box, iron stove was introduced within those sacred precincts, with a labyrinth of pipe, bending and crooking in every direction, the effect was fearful. Two or three fainted from the heat it occasioned, and shutters sufficient would not have been found to convey the expectant swooners to more airy places, had not an old deacon gravely informed the congregation, that the stove was destitute of both fire and fuel.

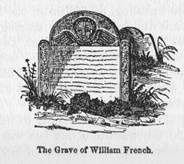

Just beyond the meeting-house lies the old burying-ground, crowded with the silent dwellers of the last hundred years. These tenants pay no rent for their lodgings, and shall never know any reckoning day but the last. The paradises of the dead which are found to-day in the suburbs of almost every American city, speak well for the taste and refinement of the age; but beautiful as they may be, there is a coldness around them of which the marble piles that adorn them are fitly emblematic. More acceptable to a chastened taste, is the village graveyard with its truthfulness and simplicity. The humble stone, with its simple story simply told, conveys to the contemplative mind a pleasanter impression than the monument with its weary length of undeserved panegyric. There is a quaintness, too, in the old inscriptions, which is more heart-touching than the formality and stiffness of the epitaphs of a modern diction. Sometimes, too, there is noticed an original or phonetic way of spelling; and again, when poetry is attempted, the noble disdain of metre which is often seen, is sure evidence that Pegasus was either lame or was driven without bit or bridle.

Enter now this old burial-place. At the right of the path, but a short distance from the gate, stands an unpretending stone, not half as attractive by its appearance as many of its fellows. Some there are, who, like Old Mortality, take a certain innocent pleasure in endeavoring to preserve these milestones to eternity from the decay of which they are commemorative. Such may be the inclination of the reader. Stop then for a moment in this consecrated spot. Brush off the moss which has covered with verdure the letters of this simple slate stone. Put aside the long grass which is waving in rank luxuriance at its foot, and now read its patriotic record:

1775.] CONDITION OF THE COLONIES BEFORE THE REVOLUTION. 215

"IN Memory of WILLIAM FRENCH.

Son to Mr, Nathaniel French. Who

Was Shot at Westminster March ye 13th,

1775 by the hands of Cruel Ministereal tools.

of Georg ye 3d, in the Corthouse at a 11 a Clock

at Night in the 22d, year of his Age.

HERE WILLIAM FRENCH his Body lies.

For Murder his Blood for Vengance cries.

King Georg the third his Tory crew

tha with a bawl his head Shot threw.

For Liberty and his Countrys Good.

he Lost his Life his Dearest blood."

Starting with the indignant language of this epitaph as a text, it will not be amiss to explain its meaning, and collate some of the circumstances connected with the tragedy to which it refers. A correct estimate of the feelings of many of the inhabitants of Cumberland county, may be formed from the conduct of the people of Dummerston in the rescue of Lieut. Spaulding, as related in the preceding chapter. The fuel which success on that occasion added to the flame which before was not dimly burning, did not fail to increase a desire to attempt other and mare important deeds.

By the old French War, and by the depreciation of bills of credit consequent thereupon, many, in all the colonies, had become reduced in their circumstances. The sufferers were mostly those who had been officers or soldiers in the colonial service, and who now returning from their toils and struggles, found themselves weakened by suffering, their families starving around them, parliamentary acts of unusual severity enforced in the cities, creditors clamoring for their dues, and their own hands filled with paper-money worthless as rags, to pay them with. "In Boston," remarks an historian of those times, "the presence of the royal forces kept the people from acts of violence, but in the country they were under no such restraint. The courts of justice expired one after another, or were unable to proceed on business. The Inhabitants were exasperated against the Soldiers, and they against the Inhabitants; the former looked on the latter as the instruments of tyranny, and the latter on the former as seditious rioters."* In Cumberland

* MS. History of the American Revolution, among the papers of Governor William Livingston, of New Jersey, chap. iv. p. 75, in N. Y. Hist. Soc. Lib.

216 HISTORY OF EASTERN VERMONT. [1775.

county, the higher civil officers had received their appointments directly from the Legislature of New York, and still remained, as they had ever been, loyal to the King. For these reasons, and because the Colonial Assembly had refused to adopt the "non-importation, non-consumption, and non-exportation" association, there were many in the county who mingled with their enmity to Great Britain a dislike to the jurisdiction of New York and to the officers of her choice. The unfriendliness of these feelings was in no wise diminished by the disputes in regard to land titles, which since the year 1764 had at times disturbed the equanimity of the people.

As may have been already inferred from the reforms which had been proposed, the maladministration of the courts of justice in the county had become almost insufferable. So unhappy was the feeling between the people on the one hand, and the judges, sheriff, and other officers of the court, and their adherents, on the other, that the former were generally stigmatized as "the Mob," while the latter assumed the title of "the Court Party." But the time had now come when the Whigs, as the mob preferred to be called, must assert their rights as freemen, or submit to the oppressive sway of the Tories, as they chose to call their opponents. Already had the Tories begun to plan in secret measures by which "to bring the lower sort of the people into a state of bondage and slavery." "They saw," says a narrator of the events of this period, "that there was no cash stirring, and they took that opportunity to collect debts, knowing that men had no other way to pay them than by having their estates taken by execution and sold at vendue."

1775.] THE FEELING IN CUMBERLAND COUNTY. 217

differently, as "guilty of high treason." The "good people" were of opinion that men who held such sentiments "were not suitable to rule over them."

As has been previously said, the General Assembly of the province had rejected the Association of the Continental Congress. On the other hand, the inhabitants of the county had, in open convention, adopted it. By its fourteenth article, they had resolved to have "no trade, commerce, dealings, or intercourse whatsoever, with any colony or province in North America" which should not accept of, or which should in the future violate the association, and had promised to hold such as should act thus, "as unworthy of the rights of freemen, and as inimical to the liberties of their country." For these reasons they judged it "dangerous to trust their lives and fortunes in the hands of such enemies to American liberty," or to allow men who would betray them to rule in their courts of justice. Thus was their determination taken. In duty to God, to themselves, and to their posterity, they resolved "to resist and to oppose all authority that would not accede to the resolves of the Continental Congress."*

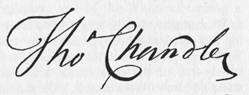

Such was the state of feeling in Cumberland county immediately previous to the commencement of the Revolution. Determined to evince by action the principles which they had openly avowed, the Whigs resolved that the administration of justice should no longer remain in the hands of the Tories, and the 14th of March, 1775, the day on which the county court was to convene at Westminster, was fixed upon as the time for carrying into execution their plans. Anxious to free themselves from the charges of haste and rashness, and to proceed as peaceably as possible, they deemed it prudent to request the judges to stay at home. For this purpose, on the 10th of March, "about forty good, true men" from Rockingham, visited Col. Thomas Chandler, the chief judge, at his residence in Chester. To their expostulations he replied that "he believed it would be for the good of the county not to have any court, as things were," but added, that there was one case of murder to be tried, which should be the only business transacted, if

* Slade's Vt. State Papers, 56. Journals Am. Cong. i. 25.

218 HISTORY OF EASTERN VERMONT. [1775.

such was the wish of the people. One of the company then remarked that the sheriff would oppose the people with an armed force, and that there would be bloodshed. The colonel declared, "he would give his word and honor," that no arms should be brought against the people, and said that he should be at Westminster on the day previous to the opening of the court. His visitors informed him that they would wait on him at that time, "if it was his will." He assured them that their presence would be "very agreeable," returned them "hearty thanks" for their civility, and parted with them in a friendly manner. Noah Sabin, one of the associate judges, firm in the performance of what he deemed his duty, was very desirous that the court should sit as usual. Many of the petty officers of the court were of the same opinion. Samuel Wells, the other associate, was, as representative, in attendance on the General Assembly at New York. Among the leaders of the Whigs there was much debate as to the course they should pursue in carrying their plans into execution. Depending on the statements of Judge Chandler, they at first decided to let the court assemble, and then to lay before it their reasons for not wishing it to sit. But having heard that the Tories were resolved to take possession of the court-house with armed guards, they changed their plans, and determined to precede them in occupation, in order that they might make known their grievances before the session should be regularly opened.

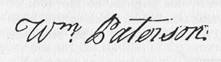

The intentions of the Whigs soon became known, especially in the southern towns of the county. On Sunday, March 12th, the day previous to the night of the "massacre," William Paterson, the High Sheriff, in conformity with the views of Judge Sabin and others, went to Brattleborough, and desired the people to accompany him on the following day to Westminster, that he might have their assistance in preserving the peace, and in suppressing any tumult that might arise. To his proposal a number assented, and on the 13th, about twenty-five of the inhabitants unarmed, except with clubs, attended him to Westminster. On the road they were joined by such as were friendly to them, and the destructive power of the company was increased by the addition of fourteen muskets. On the afternoon of the same day, a party of Whigs from Rockingham arrived at Westminster. On their way down to

1775.] THE COURT-HOUSE OCCUPIED BY THE WHIGS. 219

the Court-house they halted at the house of Capt. Azariah Wright. But the log dwelling in which the captain resided was too small to accommodate them. They therefore repaired to the log school-house, which was situated on the opposite side of the "street," and there entered into a consultation as to the best manner in which they could prevent the court from sitting. Having finished their conference, they armed themselves with sticks, obtained from Capt. Wright's wood-pile, and continued their march. On their way they were joined by a number of the inhabitants of Westminster, armed like themselves with cudgels, and having gained the point of destination, the whole party numbering nearly a hundred entered the Court-house between the hours of four and five, with a determination to stay there until the next morning, that they might present their grievances to the judges at an early hour, and endeavor to dissuade them from holding the court. Soon after this, and a little before sunset, Sheriff Paterson marched up to the Courthouse at the head of a body of sixty or seventy men, some of whom carried "guns, swords, or pistols," and others clubs or sticks.

When the sheriff had approached within about five yards of the door, he commanded the "rioters" to disperse. To this order the Whigs made no reply. Finding that he should not be able to gain admittance to the building by ordinary means, as the Whigs had placed a strong guard at all the entrances, he caused the "King's proclamation" to be read, and ordered the "mob" to depart within fifteen minutes, threatening, in case of refusal, to "blow a lane" through them, wide enough to afford an easy exit for all whom the bullets might spare. The Whigs, in reply, made known their firm determination to remain where they were, but at the same time informed the sheriff that he and his men might enter without their arms, but on no other condition. At this juncture, one of the Whigs advancing a little from the doorway, turned to the sheriff's party and asked them if they were come for war?" adding, that he and his friends had "come for peace," and should be glad to hold a parley with them. Upon this, Samuel Gale, the Clerk of the Court, drew a pistol, and holding it up, exclaimed, "damn the parley with such damned rascals as you are. I will hold no parley with such damned rascals but by this," referring to the pistol. Both parties being by this time much exasperated, a wordy rencounter ensued, in which the clerk and the sheriff

220 HISTORY OF EASTERN VERMONT. [1775.

found their equal in the tongue of Charles Davenport, a skilful carpenter from the patriotic little village of Dummerston; for when the Tories informed the "rioters" that they "should be in hell before morning," the ready carpenter replied, that if the sheriff should offer to take possession of the Court-house, the Whigs "would send him and all his men" to the same place "in fifteen minutes." The Tories now drew off a short distance, and seemed to be engaged in consultation. Regarding this as a favorable sign, the Whigs deputized three of their men to treat with them. But they soon returned, wiser only in being assured that they were "damned rascals."

About seven o'clock in the evening, Judge Chandler came into the Court-house, and was immediately asked whether he and his associate, Sabin, would consult with a committee of the Whigs as to the expediency of convening the court on the morrow. To this inquiry Chandler replied, that the judges could not enter into a discussion as to "whether his Majesty's business should be done or not, but that if they thought themselves aggrieved, and would apply to them in a proper way, they would give them redress if it was in their power." A conversation then ensued between Chandler and Azariah Wright of Westminster, who for several years had been the captain of the militia of that town, and was now the leader of the Whigs. To the statement that arms had been brought to the Court-house by the Tories, when he had given his word that such an act should not be tolerated, Chandler answered, by acknowledging the truth of what was said, but declared that this proceeding had been without his consent. To prevent an outbreak, he gave his pledge that the Tories should be deprived of their weapons, that the Whigs should "enjoy the house" without molestation until morning, and that the court would then assemble and hear what those who were aggrieved might wish to offer. Having made these promises, he departed. The Whigs thereupon left the house, and chose a committee who drew up a schedule of the subjects in regard to which they should demand redress from the court. The report was then read to the company, and was adopted without any dissent. After this Capt. Wright and his associates went, some to their homes, some to the neighboring houses, leaving, however, a guard in the Court-house to give notice in case an attack should be made in the night. The sheriff, that he might increase his own forces as much as possible, sent word to all

1775.] NORTON'S TAVERN. 221

the Tories in the neighborhood to join him without delay, and that he might lessen the power of his opponents, arrested such of the Whigs as he could take without endangering himself.

Meantime the majority of the sheriff's posse having assembled at Norton's tavern* — the Royal inn of the village — were holding a consultation as to the course they should pursue, and over their punch-bowls, filled in honor of George were deciding the fate of the "rebels." Loudly they talked of the spirit of anarchy which, originating in the disturbances of the stamped paper act of 1765, was now culminating in general dissatisfaction. Heated by their angry discussions, and inflamed by their deep potations, they were more than ready to perform the deeds of which the following hours were witness. Nor was their leader dissatisfied to find men so willing to second his murderous intentions.

Ceasing from their revelry, they, at the command of the sheriff, left the tavern in small parties, and proceeded stealthily up the hill on whose brow stood the Court-house. Unobserved as they supposed in their approach, they reached the building, and at the hour before midnight presented themselves at its doors, armed, and prepared for action. But the waning moon, tipping their bayonets with her light as they marched, had

* This tavern, which is still standing, was probably built as early as the year 1770, and was kept for many years by its owner, John Norton, who for that period was a man of wealth and influence. He belonged to an Irish-Scotch family, who in Ireland were accustomed to write the name MacNaughton. When John removed to Westminster, he omitted the prefix, and changed the orthography of the surname. After this alteration, nothing would more offend him than to be addressed by his former name. He secretly favored the cause of Great Britain during the Revolution, and was generally regarded as a Tory. Being in conversation with Ethan Allen concerning Universalism at the time of the introduction of that doctrine into Vermont, Norton remarked concerning it, "that religion will suit you, will it not, General Allen?" "No, no," replied Allen, in his most contemptuous tone, "for there must be a hell in the other world for the punishment of Tories."

222 HISTORY OF EASTERN VERMONT. [1775.

warned the sentry of their coming, and they now found guards stationed at the doors, ready to dispute with them the passages which they had hoped to find undefended. Advancing towards the door, the sheriff demanded entrance in his Majesty's name. His words were without effect. He then informed the "rioters" that he should enter, quietly if he could, or if necessary, by force, and commanding the posse to follow him, proceeded to do as he had said he would. Having gained the uppermost of the three steps, which from the outside afforded approach to the main door, he was pushed back by the guards stationed to defend it. Recovering, he renewed the attempt, but with no better success than before. To the second repulse were added blows from the clubs of the "rioters," which, though comparatively harmless, served to exasperate him on whom they fell. The sheriff now ordered his men to fire, and three guns were discharged, yet with so high an aim that the balls passed above the heads of those in the house, and lodged in the upper parts of the rooms. At the second fire the aim was lower, and the sentries were driven from their posts. The assailants having in this manner effected an entrance, pushed forward with "guns, swords, and clubs," and in the quaint words of an eye-witness, "did most cruelly mammoc" such as opposed them. Crowded in the narrow passages of the lower story of the building, on the stairs, and among the benches of the court-room, the hostile parties amid total darkness sustained for a time a hand-to-hand conflict. But the strife was of short duration. The shouts of the sheriff and his men soon announced that their deadly weapons and superior numbers had given them the victory.

Some of the Whigs escaped by a side passage, ten were wounded, two of them mortally, and seven were made prisoners. Of the sheriff's posse, two received slight flesh wounds. In the south-west corner of the Court-house, on the lower floor, was a bar-room, arranged most conveniently for those among the "judges, jury-men, and pleaders," who were inclined to be bibacious. The Tories, who immediately before the assault had aroused their courage by copious draughts, not only at the Royal tavern but at this place also, now renewed their drinking-bout, being served by the jailor, Pollard Whipple, who also acted in the capacity of bar-tender, and a brawling frolic was kept up until morning. Meanwhile the wounded and suffering prisoners, crowded in two narrow, dungeon-like rooms, destitute of the necessities which their situation demanded,

1775.] THE STATEMENT OF FACTS. 223

and deprived of light and heat, were compelled during the long and dark watches of the night, to bear the insane taunts of the victors, and listen to their vile abuse.

On the morning of the 14th, all was tumult and confusion. The judges, however, opened the court at the appointed hour, but instead of proceeding with business, spent the little time they were together in preparing "a true state of the Facts Exactly as they happened," in the "very melancholy and unhappy affair" of the evening previous. This account, which was in the main fair and impartial, was dated "in open court," and was signed by Thomas Chandler and Noah Sabin, judges; Stephen Greenleaf and Benjamin Butterfield, assistant justices; Bildad Andross, justice of the peace; and Samuel Gale, clerk of the court. It closed with this appeal: — "We humbly submit to every Reasonable Inhabitant, whether his Majesty's courts of justice, the Grand and only security For the life, liberty, and property of the publick, should Be trampled on and Destroyed, whereby said Persons and properties of individuals must at all times be exposed to the Rage of a Riotous and Tumultuous assembly, or whether it Does not Behove Every of his Majesty's Liege subjects In the said county, to assemble themselves forthwith for the Protection of the Laws, and maintenance of Justice." Public feeling being much excited, the judges did not deem it prudent to call the docket, and adjourned the court until three o'clock in the afternoon. This adjournment was on the same day continued until the June term. But the court had seen its last meeting. The second Tuesday in June came, the judges have never held the session appointed for that occasion.

Meanwhile, the Whigs who had been driven from the Courthouse by the sheriff's party had not been idle. Messengers were despatched in every direction to carry the news and procure assistance. Dr. Jones, zealous in the cause of liberty, rode hatless to Dummerston, and others performed longer journeys with as little preparation. As in olden times, when the Cross of Fire — the emblem of impending war — was borne from village to village, so now, at the approach of the courier —

"In arms the huts and hamlets rise;

From winding glen, from upland brown

They poured each hardy tenant down.

* * * * *

The fisherman forsook the strand,

224 HISTORY OF EASTERN VERMONT. [1775.

The swarthy smith took dirk and brand;

With changed cheer, the mower blithe

Left in the half-cut swathe his scythe;

The herds without a keeper strayed,

The plough was in mid-furrow stayed;

Prompt at the signal of alarms,

Each son of freedom rushed to arms."

By noon, more than four hundred persons had assembled in Westminster, of whom about one-half were from New Hampshire. One company from Walpole was commanded by Capt., afterwards Col. Benjamin Bellows, of revolutionary distinction. Capt. Stephen Sargeant brought his company from Rockingham. Guilford furnished an organized band, and the Westminster militia were in full force under their old leader, Azariah Wright. Such a body as this, the adherents of the court were not prepared to encounter. Those of the Whigs who had been imprisoned the night previous, were soon liberated, and before evening the judges with their assistants, and such of their retainers as could be taken, were placed in arrest. The court-room in which they were confined, and which had been the scene of a part of the struggle, presented a spectacle which told but too plainly of the rage which had characterized the actions of the combatants. The benches were broken, and the braces, timbers, and studs of the unfinished room, were cut and battered by the bullets which had been fired by the Tories, after they had obtained entrance into the building. Blood was to be seen in the passages, and the stairs were stained with stiffened gore. Visitors curious to see how judges and justices appeared in prison, were admitted, four or five at a time. As night set in, the darkness seemed to render the Whigs furious. Many who had come from Dummerston and Putney "were instant with loud voices," requiring that the judges should be brought out before them, and compelled to "make acknowledgements to their satisfaction;" that the Courthouse should be pulled down or burned, and that all who had been engaged in "perpetrating the horrid massacre" should be put in irons. They even went so far in their exasperation, as to vow they would fire upon every person they should find in the Court-house, who had participated in the scenes of the preceding night. These inhuman suggestions, although seconded by the leader of the Guilford militia, and winked at by Dr. Jones, met with a strong opposition from Capt. Bellows. Firm in the cause of the people, he did not forget what was

1775.] EXCITEMENT OF THE YEOMANRY. 225

due to justice. Inflexible in his purpose, he appeared as the guardian of rights, and while he desired the punishment of the prisoners in a legal manner, he took especial care that they should suffer no violence at the hands of infuriated men.

The morning of the 15th brought with it a renewal of the scenes and feelings of the day before. In one part of the town, Leonard Spaulding, the Dummerston farmer, who a few months previous had been committed "to the Common goal for high treason against the British tyrant, George the Third," was busily engaged in examining all persons who he suspected had come to reinforce the sheriff's party. In another quarter, the beating of a drum heralded the approach of Solomon Harvey, "Practitioner of Physic," at the head of a body of three hundred men. In the centre walked four of the sheriff's posse, who had been intercepted on their way home. The whole party halted in front of the Court-house. An investigation was had, which ended more favorably than the poor prisoners had expected. The stern old doctor disarmed them, and dismissed them with a pass signed with his own name, to which was prefixed the title of Colonel.

Loud and deep were the curses which the yeomen, as they gathered from hill and valley, poured forth, when they had been correctly informed of what had occurred. Some were anxious to riddle the Court-house with ball, others begged that the sheriff might be placed in their power, so that they might punish him as it should please them. One man, with a demoniacal grill, declared that "his flesh crawled to be tomahawking" the prisoners, and frequent was the wish that murderers might be treated as such. To the presence of Capt. Bellows the officers of the court owed the security which they enjoyed, amid this maelstrom of human passion. A legal inquest having been held on the body of William French, and the guilt of his death having been charged upon the sheriff and some of his party, he and those who were already imprisoned with him were put in close confinement. On the evening of the same day, Robert Cockran, who had rendered himself conspicuous in being engaged with Ethan Allen in persecuting his Bennington neighbors who had settled under charters from New York, reached Westminster, having left his residence on the other side of the mountains, as soon as he had received information of the movements of the hostile parties. Armed with sword and pistols, he entered the village at the

226 HISTORY OF EASTERN VERMONT. [1775.

head of forty or more of the Green Mountain Boys. A year before, Governor Tryon had offered a reward of fifty pounds for his arrest. As he advanced, he tauntingly asked of those who he supposed were favorers of the court party, why they did not take him, and obtain the compensation. In loud tones he declared his intentions of seizing certain men who had aided the sheriff, provided "they continued upon earth," and in an incorrect citation from Scripture, expressed a determination of ascertaining "who was for the Lord, and who was for Balaam."

Mrs. Gale having obtained an opportunity of speaking with her husband, was requested by him to inform her mother of his imprisonment, and transmit the same information to her father, Col. Wells, and to Crean Brush, who, as representatives, were then in attendance on the General Assembly in the city of New York. This message having been delivered to Mrs. Wells at Brattleborough, she immediately made arrangements with Oliver Church of that town, and Joseph Hancock, of Hopkinton, Massachusetts, to act as couriers, and a little after midnight they started on their journey.*

By the morning of Thursday, the 16th, "five hundred good martial soldiers, well equipped for war," had assembled in Westminster, besides others who had come as private citizens. After consultation, it was decided that some permanent disposition ought to be made of the prisoners then in jail. In order to satisfy the people who had collected, a large committee was chosen to represent them, which committee was composed both of residents and non-residents of the county. The accused were then examined, and a decree was passed that those who had been the leaders in the "massacre" should be confined in the jail at Northampton, Massachusetts, until "they could have a fair trial." Those who were less guilty, were required to give bonds with security to John Hazeltine, to appear at the next court of Oyer and Terminer to be holden in the county, and on these conditions were released. Meantime the town became so much crowded with visitors, that there were not houses or barns sufficient to shelter them, and food enough to support them was with difficulty obtained. It was not until the follow‑

* They arrived at New York on the following Monday, having been one hundred and ten hours in travelling a distance which is now accomplished in an eleventh part of that time. John Griffin, Arad Hunt, and Malachi Church, were afterwards sent express to the same place with confirmatory information.

1775.] SKETCHES OF THE LIBERTY-MEN. 227

ing Sunday that preparations could be completed for conveying the prisoners down the river. In this interval they were visited by hundreds of those whom they had formerly oppressed, and who, now that their persecutors were bound, were ready to return upon them the bitterness which they had so lavishly expended when in power.

Regarding the Whigs or Liberty-men who were killed and wounded in the affray, the following facts have been collected. William French,* son of Nathaniel French, resided in Brattleborough, but so near the southern line of Dummerston, that he was sometimes claimed as an inhabitant of that town.† In the

* Many of the facts in this biographical notice were obtained from the Honorable Theophilus Crawford, of Putney, who was born at Union, Connecticut, April 25th, 1764. In the year 1769, his father, James Crawford, moved with his family to Westminster. At that time no large boats ran above Hadley Falls, and the journey thence up the river, was performed in a log boat or canoe. On the evening of May 25th, the adventurers made Fort Dummer, in the midst of a heavy rain-storm. This old defence was then inhabited by the French family. As soon as the arrival of the strangers had been made known, William French hurried down to the boat, took the little Theophilus in his arms, and carried him to the fort. Here the young traveller spent the first night of his Vermont life. On reaching Westminster, James Crawford took up his abode in a log building which formerly stood on the site of the residence of John May, Esq., lately deceased. At the time of the "massacre," he lived in the west part of the town. He was present at the burial of French, having previously assisted in laying out the corpse. On the morning after the affray, Luke Knowlton of New Fane, who was then a favorer of the court faction, set out with eleven others on his return home. Passing along a cross-road leading from Westminster to New Fane, the party stopped at the house of James Crawford, and asked for something to drink. Mrs. Crawford, whose sentiments were the same as her husband's, replied, "we have no drink for murderers," and refused compliance with the request. Knowlton, who was a polite man, bowed as this answer was given, and went his way, as did his companions theirs, thirsting. Theophilus Crawford was a member of the Council from 1816-1819; held the office of sheriff of Windham county in the year 1819; received the appointment of delegate to the State Constitutional Convention in 1822; and represented the town of Putney in the Assembly at the session of 1823. His death occurred in January, 1856.

† When, in the year 1784, Theophilus Crawford was on his way to Guilford to assist in quelling the disturbances which had arisen from the insubordination of the "Yorkers," he stopped at the French house, then "the most north-eastern dwelling in Brattleborough." Mrs. French, who was still living, and in whose mind the remembrance of the loss of her son was still fresh, entreated him not to expose himself to the rage of the enemy, and warned him to shun the dangers which threatened him from the infuriated "Guilfordites." Her fears, though more imaginary in this instance than real, afford a proof of the terror with which she must at all times have regarded the scenes of that March night — a night so fatal to her highest and best expectations. The site of the French house forms a portion of the farm which is now familiarly known as "the Old Wellington Place," and is on the right hand side of what was, a few years ago, the stage road.

228 HISTORY OF EASTERN VERMONT. [1775.

census of 1771, his father's name appears in the lists of both towns. The people of Brattleborough who lived in his immediate neighborhood, were mainly favorers of the court party, and "some of them were in the sheriff's band, that officer being himself an inhabitant of that town." As for young French, his principles were those which he had received from his father.* Finding sympathy in the opinions of the liberty-loving people of Dummerston, he generally acted with them on questions relating to the public weal. He held no official station, but appears to have been much esteemed for his bravery and patriotism, "and the treatment he afterwards received from his opponents, sufficiently attests how much they feared his influence." At the time of his death he was not twenty-two years of age. In person, he was of a medium size and stature, and in the words of one who knew him, was esteemed as "a clever, steady, honest, working farmer." He had come to Westminster with a number of others, his companions, in order to obtain and secure what he had before supposed he had a right to demand, namely, the privilege of being governed by sound laws and sound principles, and of restraining the advance of oppression. Being, undoubtedly, more ardent than others in expressing and enforcing his sentiments, he was among the first to attract attention, and in the issue was most mercilessly butchered. He was shot with five bullets in as many different places. One of the balls lodged in the calf of the leg, and another in the thigh. A third striking him in the mouth, broke out several of his teeth. He received the fourth in his forehead, and that which caused his death, entered the brain just behind the ear. In this horrible condition, still alive, he was dragged like a dog to the jail-room, and thrust in among the well and wounded. So closely was the prison crowded, that those who would have gladly bound up his wounds and spoken peace and consolation to the soul that still lingered in that bleeding and mangled body, were unable to act their wishes. Through the prison doors, his enemies vented their curses upon him, telling him that they wished "there were forty more" in his condition, and shouting to his companions "that they should all be in hell before the next night." When execration failed, they mocked him as he gasped for the failing breath, and made "sport for

* At the Westminster Convention, held February 7th, 1775, Nathaniel French was chosen to represent Brattleborough in the Standing Committee of Correspondence.

230 HISTORY OF EASTERN VERMONT. [1775.

And, dying, mention it within their wills,

Bequeathing it, as a rich legacy,"

Unto their issue."

Although the courts had been stopped, yet the spirit of law had not fled from the county. A coroner's jury was assembled to inquire into the cause of the death of French, and the proceedings on that occasion were conducted in the most solemn and deliberate manner. The original report of the investigation is still preserved, and is in these words:—

"New York

Cumberland County.

An Inquision* Indented & Taken at Westminster the fifteenth Day of March one Thousand Seven Hundred and Seventy five before me Tim° Olcott Gent one of the Corroners of the County afore Said upon the Veiw of the Body of William French then and there Lying Dead upon the oaths of Thos Amsden, John Avorll, Joseph Pierce, Nathael Robertson, Edward Hoton, Michal Law, George Earll, Daniel Jewet, Zachriah Gilson, Ezra Robenson, Nathaniel Davis, Nathaniel DoubleDee, John Wise, Silas Burk, Elihue Newel, Alexr Pammerly, Joseph Fuller Good and Lawfull men of the County afore Said who being Sworn to Enquire on the part of our Said Lord the King when where how and after what manner the Said Wm French Came to his Death Do Say upon their oaths that on the thirteenth Day of March Instant William Paterson Esqr Mark Langdon Cristopher Orsgood Benjamin Gorton Samuel Night and others unknown to them assisting with force and arms made an assalt on the Body of the Said Wm French and Shot him Through the Head with a Bullet of which wound he Died and Not Otherways in witness where of the Coroner as well as the Juryors have to this Inquision put their hands and Seals att the place afore Said."

On the same day, he was buried with military honors, his funeral being attended by all the militia of the surrounding country, who paid their final adieu to the ennobled dead in the salute which they fired above his grave. The smoke rolled off from the freshly turned earth, and, as the thunder of the musketry echoed over the beautiful plains of Westminster and reverberating among the distant hills, finally died away into silence those determined men who had gathered at the sepul‑

* Inquisition was intended, same as inquest.

1775.] SKETCHES OF THE LIBERTY-MEN. 231

ture of the first victim to American Liberty and the principles of freedom, vowed to avenge the wrongs of their oppressed country, and kindled in imagination the torch of war, which so soon after blazed like a beacon-light at Lexington and Bunker Hill.

Daniel Houghton, who was mortally wounded during the "massacre," came originally from Petersham, Massachusetts, and previous to his death was a resident of Dummerston. The idea was general, for a time, that he would recover from his injuries, and it is for this reason that his name is not oftener found in connection with that of French. But in the records of Dummerston, the "murthering of William French and Daniel Houghton" is spoken of as an article of history, which was then received without doubt or disagreement, and in the account of a meeting held in that town on the 6th of April, less than a month after the event, is a memorandum of a committee who were appointed to "go to Westminster there to meet other committees, to consult on the best methods for dealing with the inhuman and unprovoked murtherers of William French and Daniel Houghton." Houghton, who was wounded in the body, survived only nine days.* He was buried in the old graveyard at Westminster, not far from the last resting-place of French. For many years there was a stone, shapeless and unhewn, which marked the spot where he lay; but even this slight memorial has at length disappeared from its place, and no one can now mark with accuracy the locality of his grave.

Jonathan Knight, of Dummerston, received a charge in the right shoulder, and for more than thirty years carried one of the buck-shot in his body. One White, of Rockingham, was severely wounded in the knee by a ball, and was in consequence for a long time incapacitated for labor.† Philip Safford, a lieutenant of the Rockingham militia, was in the Court-house at the time the attack was made. Most of the Whigs who were in his situation fled by a side entrance after a short conflict with their

* Houghton died at Westminster in a house situated a little northwest of the Court-house, and but a short distance from it. It was then occupied by Eleazer Harlow. Most of those who were wounded were taken to the house of Azariah Wright, and were treated with the most careful consideration by the patriotic captain.

† After remaining three months at Capt. Wright's house, he was taken to the river on a litter, and was conveyed by water to some place where he could obtain the services of a more skilful physician, than was to be had at Westminster

1775.] SKETCHES OF THE LIBERTY-MEN. 229

themselves at his dying motions." Between the hours of three and four on the next morning, Dr. William Hill, of Westminster, was allowed to visit him; but assistance had come too late. Death had released the martyr from his sufferings.* On the day after the affray the name of French was on every lip, and hundreds visited his corpse, anxious to

" ——— dip their napkins in his sacred blood;

Yea, beg a hair of him for memory,

* Calvin Webb, of Rockingham, whose retentive memory supplied several facts which have been, and others which will be recorded, and who was nearly eighteen years old when the events above narrated occurred, has said: "At the time of the Court-house affray, I lived in Westminster, but was not present at the scene. Heard of it the next day from a little man, familiarly known as Hussian Walker, a mighty flax-dresser, who was in the engagement. Soon after this I started off in company with several other youngsters, whose names I have forgotten. Many people were going in the same direction. It was about the middle of the day when I reached the Court-house, and soon after my arrival, I saw the body of French, who had been shot the night before. A sentry was stationed to guard the corpse, as it lay on the jail-room floor. The clothes were still upon it, as in life. The wounds seemed to be. mostly about the head; the mouth was bloody, and the lips were swollen and blubbered."

Joshua Webb, the father of Calvin, was for several years a merchant or trader, at Union, Connecticut, but failing in business removed to Ashford, an adjoining town, where he continued a few years, being engaged in paying his debts and settling his affairs. In October, 1765, he came to Westminster, and was employed by the town to teach school the succeeding winter. The house which he occupied was "a large, open building," and the school was probably the first kept in Westminster. In the spring of 1766, having sent for his wife and children, young Calvin among the number, he with them took up his abode in Rockingham, where he resided a year. Displeased with the locality he went back to Westminster, and hired of Col. Benjamin Bellows a tract of land in the north part of the town, which had been previously improved by one Farwell, and is now known as "the Church farm." There he lived ten years. At the expiration of this period, he bought a farm and built him a house at Rockingham, where he lived until his death, which occurred in 1808. He was very active in the formation of the new state of Vermont, and was a member of the Dorset Conventions of September 25th, 1776, and January 15th, 1777. On the latter of these occasions, the district of Vermont was declared free and independent. He afterwards represented the people of Rockingham in the state Assembly, during the years 1778 and 1783, and was the first clerk of that town.

His son Calvin was born at Union, July 31st, 1757, and having removed with his father to the "New Hampshire Grants," became a citizen of Rockingham at the time of his father's removal to that town. Here, he passed the remainder of his life, respected by all who knew him. His death occurred in the year 1854. The assistance obtained from him and acknowledged in this note, was communicated in the winter of 1852. Although the narrator was then in his ninety-fifth year, yet his mental faculties appeared unimpaired, and the vividness with which he would describe the scenes of his youth, bore, evidence to the strength of the impressions which the mind receives in its early freshness.

232 HISTORY OF EASTERN VERMONT. [1775.

opponents. But he, determined to depart by a more honorable passage, sallied out at the main door, bludgeon in hand, knocked down eight or ten who endeavored to arrest him, and received in return several severe cuts on the head from a sabre wielded by Sheriff Patterson.

From a deposition made before the Council of New York, by Oliver Church and Joseph Hancock, the messengers who bore the news of the "massacre" southward, it would appear that, after the first volley from the sheriff's party, for the purpose of intimidating the "rioters," the latter returned the fire from the Court-house; that "one of their Balls entered the Cuff of the Coat of Benjamin Butterfield, Esquire, one of his Majesty's Justices of the Peace for the said County of Cumberland, which went out of the elbow without hurting him, and another went through his Coat Sleeve and just grazed the skin. That a pistol was discharged by one of the Rioters at Benjamin Butterfield, the Son of the above named Justice Butterfield, so near that the Powder burnt a large hole in the breast of his Coat, and one William Williams received a large wound in the head by one of the Balls discharged by the said Rioters." Another deposition made by John Griffin, contains a declaration that the Rioters returned a Discharge of Guns or Pistols on their part," and in the statement of the judges, it is asserted that the "rioters fought Violently with their clubs, and fired some few fire-arms at the Posse, by which Mr. Justice Butterfield received a slight shot in the arm, and another of the Posse received a slight shot in the head with Pistol Bullets." The account of one of the newspapers* of the time, is, that the first fire of the sheriff's posse "was immediately returned from the Court-house, by which one of the Magistrates was slightly wounded, and another person shot through his clothes." In another,† it is recorded that "the rioters fired once or twice on the sheriff's party, but did no damage."

As opposed to a part of these assertions, the Whigs declared that they had no fire-arms at the time of the attack, and this statement is substantiated by eye-witnesses, some of whom were, until within a few years, alive, and by a sufficient amount of unbiased evidence. That some of the Court party were wounded in the affray, there is no doubt; but the injuries they received, except those "inflicted by bludgeons," were from

* New York Journal, or General Advertiser: Thursday, March 23d, 1775.

† Essex Gazette, Salem, Massachusetts; vol. vii., March 14th-21st, 1775.

1775.] TORY DEPOSITIONS. 233

their own friends. The fight, it will be remembered, was carried on in darkness. To explain this contradiction in regard to the use of fire-arms by the Whigs, and to furnish a clue to all the other discrepancies which appear in the narrations of the opposing parties, a knowledge of accompanying circumstances is alone requisite. The newspaper press, controlled by those favorable to royal government, and opposed to revolutionary action, sided with the supporters of established law, regardless of its corrupt administration, and concealed or misrepresented the true causes which were forcing the lovers of liberty throughout the colonies to throw off the burdens which were oppressing them. The depositions, although given under oath, had been previously supervised by the Tory representatives in the Legislature of New York from Cumberland county, and were, no doubt, colored by them in such a manner as to make the cause of the Whigs appear in its worst light. Men, most violent in the measures which they were ready to adopt to suppress the first outbreathings of liberty and right, were not those who would scruple to exaggerate and falsify in order to achieve the ends they had proposed.*

* As testimony corroborative of the position assumed in the text, the following extracts from printed and MS. documents and verbal relations, are presented. In the report of the committee who were chosen by the people of Cumberland county and others, to prepare an account of the affray, occur these words: "We, in the house, had not any weapons of war among us, and were determined that they [the sheriff and his posse] should not come in with their weapons of war, except by the force of them." The testimony of Theophilus Crawford was, that "the Whigs had not so much as a pistol among them," and in proof of the state of feeling previous to the fight, he declared that "a man named Gates, of Dummerston, started for Westminster, armed with a sword," and that "the people would not let him proceed until he had laid aside the offensive weapon." To the same effect Calvin Webb. "The liberty men had no guns when they first came, but after French was killed, they went home and got them." Azariah Wright, a grandson of the sturdy captain of the same name, who was so active in the cause of the sons of freedom, has written to the author, by the dictation of his father, Salmon Wright, who, a lad of twelve or thirteen, was present at the burial of French, in these words: "There were no arms carried by the liberty party, except clubs which were obtained by the Rockingham Company at my grandfather's wood-pile. There were no Tories wounded, save those knocked down by the club of Philip Safford." When questioned with reference to the assertions of Hancock and Church, his language, dictated as before, was this: "In regard to the statements in the Tory depositions, father says they are all fudge! that there were no weapons carried or used by the liberty men, except the afore-mentioned clubs. This is a fixed fact." Additional proof might be accumulated; but it is probable that enough has been said to satisfy the reader that the only weapons, offensive or defensive, carried by the Whigs, were clubs and staves.

234 HISTORY OF EASTERN VERMONT. [1775.

As furnishing the less important incidents connected with the affray, tradition affirms, that a certain Joseph Temple of Dummerston, carried his food in a quart pewter basin, which, placed in a kind of a knapsack, was strapped over his shoulders. During the firing the basin was struck twice by the bullets, which left their marks upon it but did not perforate it, and its owner escaped unhurt. This novel life-preserver was kept in the family of his descendants for many years, but finally found its way to that place of deposit of articles valuable for their antiquity, the cart of a tin pedlar. Another brave man of the same town, hight John Hooker, escaped with the loss of the soles of his boots, which were raked off by a chance shot from the enemy. But the discomfiture was only temporary; the art of the shoemaker was potent to restore the wanting portions, and the boots were afterwards worn by their owner with feelings of pride and satisfaction. Many a man more distinguished but less valiant than John Hooker, has in the time of battle found safety in trusting to his soles, and that, too, in a manner not one half as honorable!

To dignify the events of the 13th of March, the Muses were not ashamed to lend their assistance. The following lines, exhumed from the brain of an old man, where they had slept undisturbed for more than three quarters of a century, afford not only a rare specimen of Hipponactic composition, but, as far as they go, contain a spirited and concise account of the affray.*

"March ye thirteenth, in Westminster there was a dismal clamor,

A mob containing five hundred men, they came in a riotous manner,

Swearing the courts they should not set, not even to adjournment,

But for fear of the Sheriff and his valiant men, they for their fire-arms sent.

* These lines are supposed to have been the production of John Arms, a young man who resided in Brattleborough, and who was a favorer of the Court party. They were communicated orally by Calvin Webb, of whom mention has been already made. Regarding them as expressing the sentiments of an opposer of the "mob," the eleventh verse furnishes another proof that stout cudgels were the only weapons which the mob carried. Arias is said to have possessed mental qualities of no mean order. Physically, he was not strong, and died young. By a vote of the Council of Vermont passed June 15th, 1782, it appears that John Arms of Brattleborough, who, at the age of fifteen, in the year 1775, joined the "enemies of this and other American States," and afterwards returned and asked pardon, was forgiven "and restored to the privileges of the State "on taking the oath of allegiance. The person referred to in this vote, and the poet of the "Westminster Massacre," are supposed to he identical.

1775.] THOMAS CHANDLER, JR. 235

The Protestants that stood by the law, they all came here well armed;

They demanded the house which was their own, of which they were debarred.

The Sheriff then drew off his men to consult upon the matter,

How he might best enter the house and not to make a slaughter.

The Sheriff then drew up his men in order for a battle,

And told them for to leave the house or they should feel his bullets rattle.

But they resisted with their clubs until the Sheriff fired,

Then with surprise and doleful cries they all with haste retired.

Our valiant men entered the house, not in the least confounded,

And cleared the rooms of every one, except of those who were wounded."

With one exception the officers of the Court were opposed to any interference on the part of the people. Thomas Chandler Junior, one of the assistant justices and a son of the chief judge, held views repugnant to those of his colleagues and superiors. On the day of the outbreak, a large body of the inhabitants of Chester having started to go to Westminster, Chandler was questioned as to the object of their journey. In reply, he stated that they had gone "to petition the Inferior Court of Common Pleas not to sit or proceed on business." Being asked whether it would not have been better had a committee been delegated to proffer the request of the people, he answered, that if those who had gone committed no violence, they could not be indicted for riot, and further remarked, that the court ought not to sit because "the attorneys vexed the People with a multiplicity of suits," the "sheriff of the County was undeserving to hold his office," and "had bad men for his deputies." He also gave it as his opinion, that if the court should attempt to proceed on "business of a civil nature," the people would put a period to the session. So thoroughly was he convinced of the injustice and petty tyranny that had attended the administration of law, that he was "very zealous" that the people should apply the remedies which they subsequently used with so much effect.*

Of the court party who had been imprisoned, Thomas Chandler, the chief judge, Bildad Easton, a deputy sheriff, Capt. Benjamin Burt, Thomas Sergeant, Oliver Wells, Joseph Willard,

* MS. deposition of Elijah Grout, relative to Thomas Chandler, Jr.

236 HISTORY OF EASTERN VERMONT. [1775.

and John Morse, were released on the 17th, having given bonds with security to John Hazeltine, to appear and take their trial at such time as should be appointed. Thomas Ellis, against whom no charge was found, was set at liberty, unconditioned Noah Sabin, one of the side judges, Benjamin Butterfield, an assistant justice, William Willard, a justice of the peace, William Paterson, the high sheriff, Samuel Gale, the clerk, Benjamin Gorton, a deputy sheriff, Richard Hill, William Williams, and one Cunningham, were, by a vote of the committee of the people, reserved for confinement in the jaol at Northampton, Massachusetts. On Sunday the 19th, these nine prisoners set out on their march, being attended by a guard of twenty-five men under the command of Robert Cockran, and by an equal number of men from New Hampshire, led by a certain Capt. Butterfield, an inhabitant of that province. Having reached Northampton on the 23d, they were there imprisoned, and remained in durance nearly two weeks.

A paragraph in a New York paper of this period, declared that "the gentlemen who had fallen into the hands of the insurgents" were to be removed by virtue of a writ of habeas corpus from Northampton to that city, where they would be "regularly tried in order to their enlargement." On the 3d of May, they had reached New York, but it is not probable that the offences with which they were charged were ever subjected to a legal investigation. The war of the Revolution had now become a reality, and the causes which produced it began to be merged in the results to which those causes had given birth.*

The news of the affray reached New York on the 21st of March, through the medium of the expresses, Church and Hancock. The Council were immediately summoned, and were informed by Lieutenant-Governor Colden, that "violent Outrages and Disorders" had lately happened in Cumberland county. At his desire, Samuel Wells and Crean Brush were called in, who repeated the statements they had received. By the advice of the Council, the messengers were directed to embody their account in the form of depositions, and the Lieutenant-Governor was requested to send the depositions to the General Assembly then in session, together with a message "warmly urging them to proceed immediately to the consideration" of such measures

* New York Gazette, Monday, April 10th, 1775.

1775.] MESSAGE FROM THE LIEUTENANT-GOVERNOR. 237

as would prevent the recurrence of "Evils of so Alarming a Nature," and bring "the principal Aiders and Abettors of such Violent Outrages to Condign Punishment."

The depositions were prepared on the 22d, and having been witnessed by Daniel Horsmanden, the secretary of the province, were sent on the 23d to the General Assembly, accompanied by a message from the Lieutenant-Governor, of which the following is a copy:—

"GENTLEMEN: You will see, with just indignation, from the papers I have ordered to be laid before you, the dangerous state of anarchy and confusion which has lately arisen in Cumberland county, as well as the little respect which has been paid to the provisions of the Legislature, at their last sessions, for suppressing the disorders which have for some time greatly disturbed the north-eastern districts of the county of Albany and part of the county of Charlotte.*

"You are called upon, gentlemen, by every motive of duty, prudence, policy, and humanity, to assist me in applying the remedy proper for a case so dangerous and alarming.

"The negligence of government will ever produce a contempt of authority, and by fostering a spirit of disobedience, compel, in the sequel, to greater severity. It will therefore be found to be not only true benevolence, but also real frugality, to resist these enormities at their commencement; and I am persuaded, from your known regard to the dignity of government, and your humanity to the distressed, that you will readily strengthen the hands of civil authority, and enable me to extend the succour and support which are necessary for the relief and protection of his Majesty's suffering and obedient subjects, the vindication of the honour, and the promotion of the peace and felicity of the colony."

The message, and the papers connected with it, were referred to the consideration of a committee of the whole house. On the 30th, the house resolved itself into a committee of that nature. The message and depositions were again read, and the witnesses were re-examined. By a vote of fourteen to nine, the committee advised that a provision should be made "to enable the inhabit‑

* Reference is had to a series of outrages which had been committed on the New York settlers residing west of the Green Mountains, by Ethan Allen, Seth Warner, and the "Bennington Mob," as they and their adherents were termed. See Doc. Hist. N. Y., iv. 891-903.

238 HISTORY OF EASTERN VERMONT. [1775.

ants of the county of Cumberland to reinstate and maintain the due administration of justice in that county, and for the suppression of riots." The Speaker having resumed the chair, the chairman of the committee presented his report, whereupon Crean Brush moved, "that the sum of one thousand pounds be granted to his majesty, to be applied for the purposes enumerated in the report." A stirring debate ensued, but the motion was finally carried, twelve voting for and ten against it. Every Whig member present, and several of the ministerial party, voted against the measure, and in the majority of two the vote of the Speaker was included.

On the 3d of April, the last day of the last session of the General Assembly of the province of New York, the Treasurer of the Colony, on a warrant from the Lieutenant-Governor or the Commander-in-Chief, and by the advice of the Council, was directed to pay the sum which had been voted for the benefit of the people of the county. Soon after this appropriation had been made, some of the officers of the court presented an account of the expenses which had been incurred by them and persons in their employ, in suppressing the disturbances in the month of March previous. By an order of the Council, the sum of one hundred and ninety-two pounds nineteen shillings and one farthing, the amount claimed, was paid to Samuel Wells, William Paterson, and Samuel Gale. This was the first draft made upon the funds which had been set apart for such purposes. Although a few of the sufferers were reimbursed by the appropriation, yet the general effect upon the county, as far as the control of the conduct of the inhabitants was concerned, was scarcely perceptible.

In presenting to Lord Dartmouth an account of his official conduct, contained in a report dated April 5th, Lieutenant-Governor Colden referred to the course he had pursued in endeavoring to protect the rights of the crown in Cumberland county, in these words: "It was necessary for me, my Lord, to call upon the Assembly for aid, to reinstate the authority of government in that county, and to bring the atrocious offenders to punishment. They have given but one thousand pounds for this purpose, which is much too small a sum; but the party in the Assembly who have opposed every measure that has a tendency to strengthen or support government, by working on the parsimonious disposition of some of the country members, had too much influence on this occasion. I am now

1775.] LIEUT.-GOV. COLDEN'S DISPATCHES. 239

waiting for an answer from General Gage, to whom I have wrote on this affair in Cumberland. By his assistance I hope I shall soon be able to hold a court of Oyer and Terminer in that county, where I am assured there are some hundreds of the inhabitants well affected to government; and that if the debts of the people who have been concerned in this outrage, were all paid, there would not be a sixpence of property left among them."

In answer to the request of Colden, it was commonly reported at the time, that Gage, who was then at Boston, sent a number of arms to New York by a vessel named "the King's Fisher." Whatever may have been the fact, "the affair at Lexington" diverted the attention of government from the proposed method of re-establishing the authority of the crown in the interior of the province, and led to a different disposition of the bayonets, at whose point obedience and submission were to have been secured.*

Inasmuch as the inhabitants of Bennington and the vicinity who held under New Hampshire, had for some years previous been engaged in quarrels with the New York settlers, there are those who have supposed that the doings at Westminster must have originated in disputes regarding the titles of land. This opinion is very erroneous. Less than a month from the time of the affray, Colden, in his official dispatches to Lord Dartmouth, commenced an account of the "dangerous insurrection," by declaring that a number of people in Cumberland county had been worked up by the example and influence of Massachusetts Bay, "to such a degree, that they had embraced the dangerous resolution of shutting up the courts of justice." After a concise description of attending circumstances, he concluded in these words: "It is proper your Lordship should be informed, that the inhabitants of Cumberland county have not been made uneasy by any dispute about the Title of their Lands. Those who have not obtained Grants under this governmt, live in quiet possession under the grants formerly made by New Hampshire. The Rioters have not pretended any such pretext for their conduct. The example of Massachusetts Bay is the only reason they have assigned. Yet I make no doubt they will be joined by the Bennington Rioters, who will endeavor to

* London Documents, in office Sec. State N. Y., vol. xlv. Doc. list. N. Y. iv. 915.

240 HISTORY OF EASTERN VERMONT. [1775.

make one common cause of it, though they have no connection but in their violence to Government." An opinion like this, and from such a source, is sufficient to show that the causes which incited the "Bennington Mob" to deeds of violence, were in no respect identical with those which determined the people of Cumberland county to prevent the sittings of the court.