CHAPTER I II III IV V VI VII VIII IX X XI XII XIII XIV XV XVI XVII XVIII XIX XX XXI ]

CHAPTER III.

FRONTIER LIFE.

Preparations for Defence — Life of the Frontier Settlers — Soldiers' Quarters — Diversions of Spring, Summer, Autumn, Winter — Effects of a Declaration of War — Grants of Townships on Connecticut River by Massachusetts — Number One or New Taunton — Conditions of a Grant — First Settlement of New Taunton, now Westminster — The place abandoned — Re-settled — Proposition to Settle the Coos Country — John Stark — Convention at Albany — Incursion at Charlestown — Birth of Captive Johnson — Inscription commemorative of the Circumstance — Other Depredations — Defences — The Great Meadow — Its Settlement — Partisan Corps — The Life of a "Ranger" — Continuation of Incursions — Attack on Bridgman's Fort — Captivity of Mrs. How — Attack near Hinsdale's Fort — Dispute as to the Maintenance of Fort Dummer — Death of Col. Ephraim Williams.

THE peace of Aix-la-Chapelle, concluded on the 18th of October, 1748, and proclaimed at Boston in January, 1749, although it put an end to the war between England and France, did not immediately restore tranquillity to the colonies. Early in the next year, hostile Indians began as usual to hover around the frontier settlements, and on the 20th of June, a party of them in ambush shot Ensign Obadiah Sartwell, of Number Four, as he was harrowing corn in his house-lot, and took captive Enos Stevens, son of the renowned captain. About the same time Lieut. Moses Willard, in company with his two sons and James Porter Jr., discovered at the north of West river mountain five fires, and numerous Indian tracks; and as Mr. Andros was going from Fort Dummer to Hinsdell's garrison, he saw a gun fired among some cattle as they were grazing but a short distance from him. These indications were enough to awaken suspicions of a bloody season, and the General Court accordingly enlisted a force of fifty men to serve as scouts between Northfield and Number Four, having their head-quarters at Fort Dummer and Col. Hinsdell's garrison,

54 HISTORY OF EASTERN VERMONT. [1749.

and being under the command of Col. Josiah Willard. They continued on this service from the 26th of June to the 17th of July, and were then dismissed, it appearing that the enemy had removed from that portion of the country. Although hostilities had ceased, and notwithstanding a treaty of peace was concluded with the Indians at Falmouth in the month of September following, yet the forces were not wholly withdrawn from the frontiers. A garrison of fifteen men, afterwards reduced to ten, was continued at Fort Dummer from September, 1749, to June, 1750, and the same number of men was stationed respectively at Number Four and Fort Massachusetts during the same period.

Throughout the whole of this war, the Indians were generally successful in their attacks upon the whites, and yet there were no instances in which deliberate murder was committed, or cruel torture inflicted on those who fell into their hands. On the contrary, their captives were always treated with kindness; blankets and shoes were provided to protect them from the inclemencies of the weather, and in case of a scarcity of provisions the vanquished and victor shared alike.

Civilization in this part of the country, even if it had not retrograded during these struggles, had made but little advance, and many of the settlements which had been commenced before the war, were wholly abandoned during its progress. The people not belonging to the garrisons and who still remained on the frontiers, lived in fortified houses which were distinguished by the names of the owners or occupants, and afforded sufficient defence from the attacks of musketry. The settler never went to his labors unarmed, and were he to toil in the field would as soon have left his instruments of husbandry at home as his gun or his pistols. Often was it the case, that the woods which surrounded his little patch of cleared ground and sheltered his poor but comfortable dwelling, sheltered also his most deadly enemy ready to plunder and destroy.*

* The fortified houses were in some instances surrounded with palisades of cleft or hewn timber, planted perpendicularly in the ground, and without ditches. The villages were inclosed by larger works of a similar style. Occasionally, flanking works were placed at the angles of fortified houses, similar to small bastions. "A work called a mount was often erected at exposed points. These [mounts] were a kind of elevated block-house, affording a view of the neighboring country, and where they were wanting, sentry-boxes were generally placed upon the roofs of houses" — Hoyt's Indian Wars, p. 185.

1749.] LIFE OF THE FRONTIER SETTLERS. 55

Solitary and unsocial as the life might seem to be which the soldiers led in the garrisons — distant as they were from any but the smallest settlements, and liable at almost any moment to the attack of the enemy — yet it had also its bright side, and to a close observer does not appear to have been wholly devoid of pleasure. The soldiers' quarters were for the most part comfortable, and their fare, though not always the richest, was good of its kind. Hard labor in the woods or field, or on camp duty, afforded a seasoning to their simple repast, the piquancy of which effeminate ease never imagined. Those who kept watch by night, rested by day, and none, except in times of imminent danger, were deprived of their customary quota of sleep.

In the spring, when the ground was to be ploughed and the grain sown, with a proper guard stationed in different parts of the field, the laborers accomplished their toil. In the pleasant afternoons when the genial sunshine was bringing out "the blade, then the ear, after that the full corn," a game at ball on the well trodden parade, or of whist with a broad flat stone for a table, and a knapsack for an easy cushion, served either to nerve the arm for brave deeds, and quicken the eye with an Indian instinct, or to sharpen in the English mind that principle, which nowadays has its full development in Yankee cunning. Pleasant also was it to snare the unsuspecting salmon as he pursued his way up the river; exciting to spear him, when endeavoring to leap the falls which impeded his advance.

The grass ripened in the hot summer's day, and the crop was carefully gathered, that the "kindly cow" might not perish in the long winter, and that the soldier might occasionally renew his homely but healthful bed of hay. By and by, when the golden silk that had swayed so gently on the top of the tall stalk, turning sere and crinkled, told that the maize with which God had supplied the hunger of the Indian for ages, was ready to yield nourishment to his bitterest enemy the white, then for a while was the sword exchanged for the sickle, and the shouts of harvest-home sounded a strange contrast to the whoop of the foeman. And then at the husking, no spacious barn which had received the golden load, beheld beneath its roof the merry company assembled for sport as well as labor, but when gathered in knots of three or four, or it might be a half dozen, as they stripped the dried husk, and filled the basket with the full ears, or cast the dishonored nubbins in some ignoble corner, who doubts that their thoughts wandered back to the dear delights

56 HISTORY OF EASTERN VERMONT. [1749.

which even the puritan customs of the old Bay Province had allowed them to enjoy, and that their minds lingered around the pleasant scenes of bygone days, until fancy had filled the picture to which reality had given only the frame. This also was the season when the deer furnished the best venison, and the bear the richest tongue and steak and when there was no enemy near, to be attracted by the sound, the click of the rifle was sure premonition of a repast, which had it not been for the plainness of its appointments, would have been a feast for an epicure.

When winter had mantled the earth, then did time old woods, which had stood for ages undisturbed, feel the force of the sturdy blow, and many a noble oak yielded up its life, that the axe which wounded it might be new-handled, the fort repaired where time and the enemy had weakened it, and the soldiers warmed when benumbed by cold and exposure. Then, too, would they prepare the trap for the big moose, or on snowshoes attack him on his own premises; and when the heavy carcass arrived piecemeal at its destination, its presence spoke of plenty and good cheer for a long season.

On the Sabbath, if the garrison was provided with a chaplain, what themes could not the preacher find suggestive of God and goodness? The White Hills on one side, and on the other the Green Mountains, pointed to the heaven of which he would speak, and emblemized the majesty of him who reigned there. The simple wild wood flowers taught lessons of gentleness and mercy; and when the hand of the foe had destroyed the habitation, and widowed the wife, and carried the babes captive; when the shriek at midnight, or in the day-time the ambush in the path, told of surprise or insecurity, with what pathos could he warn them of "the terror by night," of "the arrow that flieth by day," of "the destruction that wasteth at noonday," and urge upon them the necessity of preparation not only temporally but for eternity.

Joyful was the hour when the invitation came to attend the raising of some new block-house, or of a dwelling within the walls of a neighboring garrison. As timber rose upon timber, or as mortise received tenon, and mainpost the brace with its bevel joint, tumultuously rose the shouts and merrily passed the canteen from mouth to mouth with its precious freight of rum or cider. And when the last log was laid, or the framework stood complete, foreshadowing the future house in its skeleton outline,

1749.] GARRISON-LIFE. 57

then how uproariously would the jolliest of the party in some rude couplet give a name to the building, and christen it by breaking the bottle, or climbing to the top, fasten to the gable end the leafy branch, while his companions rent the air with their lusty plaudits!

Great was the pleasure when the watchful eye of the officer detected the drowsy sentinel sleeping on guard. Forth was brought the timber-mare, and the delinquent, perched on the wooden animal, expiated his fault amid the jeers of his more fortunate comrades. When the black night had enshrouded all objects, with what terror did even brave men hear the hostile whoop of the Indian, or with what anxious attention did they listen to the knocking of some bolder warrior at the gate of their garrison, and how gladly did they hail the approach of light, driving with its presence fears which the darkness had magnified in giant proportions.

And when thus much has been said of the pleasures and of the better feelings appertaining to garrison-life, all has been said. In many instances the soldier impressed into the service was forced to fulfil an unwilling duty. Sometimes the wife or the mother accompanied the husband or son, and shared voluntarily his humble fare and hard lot. Yet there was then but little attention paid to the cultivation even of the more common graces of society, and the heart "tuned to finer issues" found but little sympathy in the continuous round of the severest daily duties.

When a war was declared between England and France, the hostile forces of those countries, on the sea or on the land, in decisive battles determined for a time, at least, the condition of either nation. But when the war was proclaimed at Boston, a series of border depredations, beginning perhaps in the slaughter of an unsuspecting family at midnight, varied with numerous petty but irritating circumstances, every act closing with an ambush attack, and a wild foray composing the conclusion, such was the result in the colonies, such was the drama, a drama of tragedy and blood. Cruelty on the one hand begat cruelty on the other, until large sums were paid by the whites for the captive Indian, or for the bloody scalp of the murdered one. And yet, on the part of the English in America, the war was not one of retaliation. They prepared their forts and their garrisons, it is true, and sent forth their scouting parties in every direction; but by the former means did they attempt to

58 HISTORY OF EASTERN VERMONT. [1735—1751.

repel the attacks of invaders, and by the latter to drive them without their boundaries. The history of the natural, inherent rights of the Indian, involves an argument too deep for these narrative pages. Still there is no one who can question the right of the settlers to defend their property, though it might be unwittingly placed on the land claimed under the law of nature, by which the Indian demanded as his own territories, those on which he had hunted, and as his streams those in which he had fished, and on which he had paddled his canoe.

Many petitions having been presented to the General Assembly of Massachusetts, in the year 1735, praying for grants of land on the Connecticut and Merrimack rivers, that body, on the 15th of January, 1735/6, ordered a survey of the lands between the aforesaid rivers, from the north-west corner of the town of Rumford on the latter stream to the Great Falls on the former, of twelve miles in breadth from north to south, and the same to be laid out into townships of six miles square each. They also voted to divide the lands bordering the east side of Connecticut river, south of the Great Falls, into townships of the same size; and on the west side, the territory between the Great Falls and the "Equivalent Lands" into two townships of the same size if the space would allow, and if not into one township. Eleven persons were appointed to conduct the survey and division. Twenty-eight townships were accordingly laid out between the Connecticut and Merrimack rivers, amid on the west bank of Connecticut river township Number One, now Westminster, was surveyed and granted to a number of persons from Taunton, Norton, and Easton in Massachusetts, and from Ashford and Killingly in Connecticut, who had petitioned for the same.*

The terms upon which the grant of Number One and of the other townships, was made, were these. Each settler was required to give bonds to the amount of forty pounds as security for performing the conditions enjoined. Those who had not within the space of seven years last past received grants of land were admitted as grantees; but in case enough of this class could not be found, then those were admitted who, having received grants of land elsewhere within the specified time, had fulfilled the conditions upon which they had received them. The grantees were obliged to build a dwelling-house

* See Appendix C.

1735—1751.] ERECTION OF MILLS. 59

eighteen feet square and seven feet stud at the least, on their respective house lots, and fence in and break up for ploughing, or clear, and stock with English grass five acres of land, and cause their respective lots to be inhabited within three years from the date of their admittance. They were further required within the same time to "build and furnish a convenient meeting-house for the public worship of God, and settle a learned orthodox minister." On failing to perform these terms their rights became forfeit, and were to be again granted to such settlers as would fulfil the above conditions within one year after receiving the grant. Each township was divided into sixty-three rights — sixty for the settlers, one for the first settled minister, another for the second settled minister, and the third for a school. The land in township Number One was divided into house lots and "intervale" lots, and one of each kind was included in the right of every grantee. As to the remainder of the undivided land, an agreement was made that it should be shared equally and alike by the settlers when divided.

Capt. Joseph Tisdale, one of the principal grantees of Number One, having been empowered by the General Assembly of Massachusetts, called a meeting of the grantees at the school-house in Taunton, on the 14th of January, 1737. A committee was then appointed to repair to the new township for the purpose of dividing the land, according to the wishes of the grantees. They were also required to select a suitable place for a meeting-house, a burying-place, a training field, sites for a saw mill and a grist mill, and to lay out a convenient road. The proprietors held a number of meetings, sometimes at Capt. Tisdale's, at other times in the old school-house, and not unfrequently at the widow Ruth Tisdale's. A sufficient time having elapsed, the allotment of the sixty-three rights was declared on the 26th of September, 1737, and proposals were issued for erecting a saw mill and a grist mill at Number One, which was now familiarly called New Taunton, in remembrance of the town where the majority of the proprietors resided. At the same time, a number of the proprietors agreed to undertake the building of the mills, and by the records of a meeting held July 8th, 1740, it appeared that the saw mill had been built, and that means had been taken to lay out a road from it to the highway. Other improvements were made at this period by Richard Ellis and his son Reuben of Easton, who having purchased eight rights in the new township, built there a

60 HISTORY OF EASTERN VERMONT. [1735-1751.

dwelling-house, and cleared and cultivated several acres of land. Some of the settlers were also engaged at the same time in laying out roads and constructing fences, who, on their return to Massachusetts, received gratuities for their services from the other proprietors.*

The grantees were preparing to make other improvements, having in view particularly the construction of a road to Fort Dummer, when, on the 5th of March, 1740, the northern boundary line of Massachusetts was settled. On finding by this decision that Number One was excluded from that province, they appointed an agent on the 5th of April, 1742, to acquaint the General Assembly of Massachusetts of the difficulties they had experienced, and of the money and labor they had expended in settling their grant, and to ask from that body directions by which they might firmly secure their rights, although under a different jurisdiction. The meeting at which this appointment was made, was probably the last held by the proprietaries under Massachusetts, and there is but little doubt that the settlement was abandoned upon the breaking out of the "Cape Breton War."

* At a proprietors' meeting held in Taunton on Tuesday, December 2d, 1740, the following appropriations were made :—

"To Mr. Richard Ellis who in a great measure as to us appears, built a dwelling-house, and broke up five or six acres of land, voted to be paid and allowed by said proprietors for both

years' service, 1739 and 1740, the sum of £45 0 0

"Voted to be paid Lieut. John Harney for himself and hand in ye

year 1739,. £10 0 0

"Voted to be paid James Washburn for his service, and part of the team, £10 0 0

"Voted to be paid Mr. Joseph Eddy for himself and one hand, and

one third part of the team,. £15 0 0

"Voted to be paid Seth Tisdale for his labour, 1739,. . £5 0 0

"Voted Jonathan Harney ye 2d, to be paid,. . £5 0 0

"Voted to be paid Jonathan. Thayer for his service in the year 1740,

on said township,. . £10 0 0

£100 0 0"

Extract from Records of Township No. 1. under Massachusetts.

In the list of the proprietors of Number One, dated November 19th, 1736, appear the names of Joseph and Jonathan Barney of Taunton. There is a tradition that one Barney came to New Taunton as early as the year 1749, that he built there a house, and erected the frame of a saw mill. When driven away by the Indians, it is said that he previously took the precaution to bury the mill irons. A certain stream in the town bore for many years the name of Barney Brook, and Barney Island, in Connecticut river, was for a long time used for farming purposes by the early settlers.

1751—1754.] NUMBER ONE RE-GRANTED. 61

In the spring of the year 1751 John Averill, with his wife, and his son Asa, moved from Northfield, in Massachusetts, to Number One. At that time there were but two houses in the latter place. One of these, occupied by Mr. Averill, was situated on the top of Willard's or Clapp's hill, at the south end of the main street. The other below the hill, on the meadow, and unoccupied, was probably the house built by Mr. Ellis and his son in 1739. In the house into which Mr. Averill moved there had been living four men, one woman, and two children. The men were William Gould and his son John, Amos Carpenter and Atherton Chaffee. Of these, Gould and Carpenter moved their families from Northfield to Number One during the summer of the same year. The first child born in Westminster was Anna Averill. Her birth took place in the autumn of 1751.

On the 9th of November, 1752, Governor Benning Wentworth, of New Hampshire, re-granted Number One, and changed its name to Westminster. The first meeting of the new grantees was held at Winchester, New Hampshire, in August, 1753, at the house of Major Josiah Willard, whose father, Col. Josiah Willard of Fort Dummer, was at the time of his death, by purchase from the original Massachusetts grantees, one of the principal proprietors of Number One.* A subsequent meeting was held at Fort Dummer, in the same year, at which permission was given to those proprietors who had purchased rights under the Massachusetts title and then held them, of locating their land as at the first. Further operations were suspended by the breaking out of the French war, and the families above enumerated were the only inhabitants of Westminster until after the close of that struggle.†

Although the treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle, as well as that with the Indians at Falmouth, had promised a respite from the bloody scenes of border warfare, yet the government of Massachusetts, knowing well the treachery of those with whom they had to negotiate or contend, still retained their forces on the frontiers.‡ Difficulties had already arisen in the eastern quar-

* Deeds conveying to him twelve of the original rights are on record.

† See Appendix D.

‡ From the 21st of June, 1750, until the 20th of February, 1752, Fort Dummer was garrisoned with ten men; fifteen were stationed at Fort Massachusetts, and the same number at Number Four. The pay allowed at this period was: to a captain, £2 2s. 8d.; to a lieutenant, £1 12s. 41d.; to a sergeant, £1 8s. 1d.; to a corporal, £1 8s. 0d.; to a private sentinel, £1 1s. 4d.

62 HISTORY OF EASTERN VERMONT. [1751—1754.

ters of New England, and from a letter written by Col. Israel Williams on the 31st of July, 1750, it would appear that the Indians were at that time expected also on the western frontier. But the season passed without any interruption from the enemy. On the 8th of December following died Col. Josiah Willard, who had been for so long a time the able and efficient commander of Fort Dummer, and was succeeded on the 18th by his son Major Josiah Willard, who had formerly had the charge of a garrison at Ashuelot.

Intelligence having reached Boston, in August, 1751, that a number of the Penobscot tribe had joined the St. Francis Indians with the design of attacking the frontier settlements, Col. Israel Williams was ordered to apprise the garrisons at Number Four, Forts Dummer and Massachusetts, of their danger. The necessary measures of defence were accordingly taken, and in consequence of this vigilant activity, no incursions were made during this summer. A plan was projected about this period of establishing a military settlement on the rich intervals at Coos, extending south from Canada, a considerable distance on both sides of Connecticut river. Many engaged in the enterprise, and in the spring of 1752 a party was sent to view Coos meadows, and lay out the townships. The Indians who claimed this territory, noticing these movements, sent a delegation from their tribe to Charlestown and informed Capt. Stevens that they should resist by force any attempt to carry the plan of a settlement into execution. Governor Wentworth having heard of their determination, deemed it best not to irritate them, and the design was relinquished.*

On the 28th of the following April, ten or twelve of the St. Francis Indians surprised four men who were hunting on Baker's river, a branch of the Merrimack. Amos Eastman and the subsequently-distinguished John Stark were made prisoners. William Stark, a brother of the latter, escaped, but David Stinson, his companion, was killed. By the way of Connecticut river and by portage to Lake Memphramagog, the captives were carried to the Indian country. Stark was at first treated with great severity, but was subsequently adopted as a son of the Sachem of the tribe, and was so much caressed by his captors that he used often to observe, "that he had experienced more genuine kindness from the savages of St. Francis, than he

* Powers's Coos Country, pp. 10-13. Belknap's Hist. N. H., ii. 278, 279.

1752—1754.] TREATY WITH THE INDIANS. 63

ever knew prisoners of war to receive from any civilized nation."*

In February, 1752, the General Court believing that the frontiers were comparatively secure, reduced the garrison at Fort Dummer to five men. In this condition it remained under the command of Josiah Willard, to whom a sergeant's pay was allowed, until January, 1754, when the same body voted that, "from and after February 20th next, no further provision be made for the pay and subsistence of the five men now posted at Fort Dummer, and that the Captain General be desired to direct Major Josiah Willard to take care that the artillery and other warlike stores be secured for the service of the government." Notwithstanding this vote, the same force and the same commander were continued until the following September. The year 1753 was one of comparative quiet. Settlements multiplied and immigration increased. But in a country, the power of whose masters had only been checked, nothing but temporary peace could be expected. A short respite from the barbarities of a savage warfare, was sure to be followed by a long period of melancholy disasters. Nor was the present instance an exception to the rule. The encroachments of the French on the Ohio, and the renewal of hostilities by the Indians on the frontiers of New England, manifested the presence of a disposition as fierce and warlike as that which had preceded the struggles of former years. On this account the home government ordered the colonies to place themselves in a state of preparation, and counselled them to unite for mutual defence. In compliance with this advice, Governor Shirley proposed to the governors of the other provinces to send delegates to Albany, to draw up articles for a protective union and hold a treaty with the Six nations. His proposition was adopted. Delegates from seven provinces met at the convention on the 19th of June, 1754. A treaty was concluded with the Indians, and on the 4th of July, twenty-two years before the Declaration of American Independence, a plan for the union of the colonies was agreed on. Copies of the plan were sent to each of the provinces represented, and to the King's Council. By the provinces it was rejected, "because it was supposed to give too much power to the representatives of the King." It met with a

* Memoir of General Stark, by his son, Concord, 1831, p. 174. Hoyt's Indian Wars, p. 260.

64 HISTORY OF EASTERN VERMONT. [1754.

similar fate at the hands of the Council, "because it was supposed to give too much power to the representatives of the people." By this disagreement, the colonies were obliged to fall back on their old system of warfare. Each government was left to contend with its enemies as best it might.*

For the defence of Massachusetts and her frontiers, during the year 1754, Governor Shirley, on the 21st of June, ordered the commanders of the provincial regiments to assemble their troops for inspection, and make returns of the state of their forces at head-quarters. The towns in the province were also ordered to furnish themselves with the stock of ammunition required by law. It was not until late in the summer that the enemy renewed their incursions on the frontiers of New Hampshire. At Baker's town, on the Pemigewasset river, they made an assault on a family, on the 15th of August, killed one woman, and took captive several other persons. On the 18th they killed a man and a woman at Stevens's town, in the same neighborhood. Terrified at these hostile demonstrations, the inhabitants deserted their abodes, and retired to the lower towns for safety, and "the government was obliged to post soldiers in the deserted places." At an early hour on the morning of the 30th, the Indians appeared at Number Four, or Charlestown, on Connecticut river, broke into the house of James Johnson, before any of the family were awake, and took him prisoner, together with his wife and three children, his wife's sister, Miriam Willard, a daughter of Lieutenant Willard, Ebenezer Farnsworth, and Peter Labaree. Aaron Hosmer, who was also in the house, eluded the enemy by secreting himself under a bed. No blood was shed in the capture, and soon after daylight the Indians set out with their prisoners for Canada, by the way of Crown Point. On the evening of the first day, the whole party encamped in the south-west corner of the present township of Reading, in Vermont, near the junction of what is now called Knapp's brook with the Black river branch. On the morning of the 31st, Mrs. Johnson, who had gone half a mile further up the brook, was delivered of a daughter, who, from the circumstances of her birth, was named Captive. After a halt of one day the march was resumed, Mrs. Johnson being carried by the Indians on a litter which they had prepared for her accommodation. As soon as her strength would permit, she was allowed to ride

* Holmes's Annals, ii. 200, 201. Hoyt's Indian Wars, pp. 260, 261.

1754.] COMMEMORATIVE STONES. 65

a horse. The journey was long and tedious, and provisions were scanty. It finally became necessary to kill the horse for food, and the infant was nourished, for several days, by sucking pieces of its flesh.*

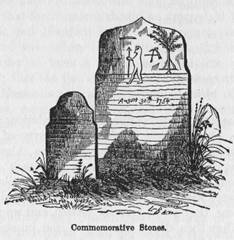

Captive Johnson was afterward the wife of Col. George Kimball of Cavendish. Upon the north bank of Knapp's brook in the town of Reading, beside the road running from Springfield to Woodstock, stand two stones commemorative of the events above recorded. The larger one is in its proper place, and the smaller one, though designed to be located half a mile further up the brook, whether by accident or intention, has always stood at its side. Tile stones are of slate, and of a very coarse texture. They bear the following inscriptions.

* When they arrived at Montreal, Mr. Johnson obtained a parole of two months, to return and solicit the means of redemption. He applied to the Assembly of New Hampshire, and, after some delay, obtained on the 19th of December, 1754, one hundred and fifty pounds sterling. But the season was so far advanced, and the winter proved so severe, that he did not reach Canada till the spring. He was then charged with breaking his parole; a great part of his money was taken from him by violence, and he was shut up with his family in prison. Here they took the small-pox, from which, after a severe illness, they happily recovered. At the expiration of eighteen months, Mrs. Johnson, with her sister and two daughters, were sent in a cartel ship to England, and thence returned to Boston. Mr. Johnson was kept in prison three years, and then with his son returned and met his wife in Boston, where he had the singular ill fortune to be suspected of designs unfriendly to his country, and was again imprisoned; but no evidence being produced against him, he was liberated. His eldest daughter was retained in a Canadian nunnery. — Belknap's Hist. N. H., ii. 289, 290. Hoyt's Indian Wars, p. 262.

5

66 HISTORY OF EASTERN VERMONT. [1754.

This is near the spot

that the Indians Encampd the

Night after they took Mr Johnson &

Family Mr Laberee & Farnsworth

August 30th 1754 And Mrs

Johnson was deliverd of her child

Half a mile up this Brook.

When troubls near the Lord is kind

He hears the captives Crys

He can subdue the savage mind

And learn it sympathy

On the 31st of

August 1754

Capt James

Johnson had

A Daughter born

on this spot of

Ground being

Captivated with

his whole Family

by the Indians.

But the enemy did not confine their depredations to the frontiers alone. On the 28th of August, a party of about one hundred Indians, from the Nepisinques, the Algonkins, and the "Abenaquies of Bekancour" made an attack on "Dutch Hoosac," about ten miles west of Fort Massachusetts. Their first appearance was at a mill which was attended by a few men. Of these, they killed Samuel Bowen, and wounded John Barnard. They then drove the rest of the inhabitants from their dwellings, killed most of the cattle, and set fire to the settlement. On the following day San Coick experienced a similar fate. The garrison at Fort Massachusetts was too weak to afford any important aid, and a party of militia from Albany, that had marched to the scene of destruction, did not arrive until the enemy had departed. The loss at Hoosac was stated. at "seven dwelling houses, fourteen barns, and fourteen barracks of wheat." That at San Coick was about the same. The property destroyed was supposed to amount to "four thousand pounds, York currency."*

* Hoyt says: "The depredations were attributed principally to the Schagticoke Indians." — Indian Wars, p. 263.

It is more than probable that the tribes mentioned in the text were the perpe‑

1754.] PLANS FOR THE FRONTIER DEFENCES. 67

To put a period, if possible, to these devastating incursions, more extensive means of defence were adopted by Massachusetts, and the charge of the western frontiers was again given to Col. Israel Williams of Hatfield. His knowledge as a topographer and engineer, enabled him, soon after, to present to Governor Shirley an accurate sketch of the frontiers of Massachusetts and New Hampshire, with plans for their defence. He recommended the abandonment of Forts Shirley and Pelham, and the erection of a line of smaller works on the north side of Deerfield river. He further proposed that the old works at Northfield, Bernardston, Colrain, Greenfield, and Deerfield should be repaired, and others built where repairs were impracticable; that Forts Dummer and Massachusetts should be strengthened and furnished with light artillery and sufficient garrisons; that fortifications should be erected at. Stockbridge, Pontoosuck, and Blanford in the south-western part of Massachusetts, and two others to the westward of Fort Massachusetts, in order to form a cordon with the line of works in New York; that the fort at Charlestown, being out of the jurisdiction of Massachusetts, should be abandoned; that, as in the former wars, ranging parties should be constantly employed along the line of forts, and in the wilderness, now the state of Vermont, and that the routes and outroads from Crown Point should be diligently watched. These plans, with the exception of that recommending the abandonment of Charlestown, were adopted, and a body of troops was ordered to be raised for the western frontiers, to be stationed as Col. Williams should direct.

Forts Dummer and Massachusetts, works of considerable strength, and containing small garrisons, were furnished with a few pieces of ordnance. The other works being diminutive block-houses, or stockaded dwellings, bearing the names of their occupants, were made defensible against musketry. These were Sheldon's and Burk's garrisons at Bernardston, on Connecticut river; Morrison's and Lucas's, at Colrain; Taylor's, Rice's, and Hawks's, at Charlemont; Goodrich's and Williams's, at Pontoosuck; and defences at Williamstown, Sheffield, and Blanford. Some of them were provided with swivels and small forces under subaltern officers. In other places, less exposed, slighter fortifications were established, some at the expense of the

trators of the acts ascribed to them. — See documents in office Sec. State N. Y., in Colonial MSS. De Lancey, 1754, vol. lxxix.

68 HISTORY OF EASTERN VERMONT. [1754, 1755.

inhabitants, and some at the expense of the province. Capt. Ephraim Williams was, as in the preceding war, appointed commander of the line of forts. His rank was raised to that of major. Deerfield was made the dépôt for the commissary stores, and a small force was stationed to protect them. The office of commissary was given to Major Elijah Williams. The fort at Charlestown, which had been built by Massachusetts, but which now lay within the boundaries of New Hampshire, required a protecting force. Governor Shirley wrote to Governor Wentworth recommending its future maintenance to the New Hampshire Assembly, and applications of a like nature were made by the inhabitants of Charlestown. The Assembly, as in former years, refused to listen to these requests. Petitions were then sent to the General Court of Massachusetts, and as a proof of the importance of the post at Charlestown, the petitioners stated that the attacks of the enemy had been sustained at that place, on ten different occasions, during the space of two years. Mention was also made of the sufferings which the inhabitants had endured by the loss of their cattle and provisions. Massachusetts again sent soldiers for the defence of the town, and a guard was continued there and at Fort Dummer until the year 1757. On the 19th of September the command of the latter station was given to Nathan Willard, with the rank of sergeant, and until June, 1755, the garrison numbered eight men. So effectually had these preparations been made, and so well were they perfected, that the incursions of the enemy ceased almost immediately. The settlers again enjoyed a temporary security, and at the close of the year it was deemed safe to lessen several of the garrisons at the smaller forts."*

The inhabitants of Westminster who were few in number and but poorly protected, being alarmed by the capture of the Johnsons at Charlestown, had removed to Walpole immediately after that event. Here they were accommodated at the house of Col. Benjamin Bellows until October, when they returned to Westminster. There they tarried until the February following, when the Averill family moved to Putney, which town, on the 26th of December, 1753, had been granted and chartered by Benning Wentworth. Fort Hill, which had been erected before the Cape Breton war, had now gone to decay and was mostly demolished. The settlements in the immediate vicinity

* Hoyt's Indian Wars, pp. 263-265. Belknap's Hist. N. H., ii. 290, 291.

1755.]. FORT AT THE GREAT MEADOW. 69

were in consequence undefended and insecure. For their mutual safety, the inhabitants of Westmoreland, New Hampshire, joined with the inhabitants of Westminster and Putney, and in the year 1755 built a fort on the Great Meadow, on the site of the house lately occupied by Col. Thomas White, near the landing of the ferry. The fort was in shape oblong, about one hundred and twenty by eighty feet, and was built with yellow pine timber hewed six inches thick and laid up about ten feet high. Fifteen dwellings were erected within it, the wall of the fort forming the back wall of the houses. These were covered with a single roof called a "salt-box" roof, which slanted upward to the top of the wall of the fort. In the centre of the enclosure was a hollow square on which all the houses fronted. A great gate opened on the south toward Connecticut river, and a smaller one toward the west. On the north-east and south-west corners of the fort, watch-towers were placed. In the summer season, besides its customary occupants, the fort was generally garrisoned by a force of ten or twelve men from New Hampshire.

The only inhabitants on the Great Meadow at the beginning of the year 1755, were Philip Alexander from Northfield, John Perry and John Averill with their wives and, families, and Capt. Michael Gilson a bachelor, his mother and his two sisters. On the completion of the fort, several of the inhabitants of Westmoreland crossed the river and joined the garrison. These were Capt. Daniel How, Thomas Chamberlain, Isaac Chamberlain, Joshua Warner and son, Daniel Warner, wife and son, Harrison Wheeler, Deacon Samuel Minott, who afterward married Capt. Gilson's mother, and Mr. Aldrich and son.* At the close of the French war, all who had removed from Westmoreland, returned, with the exception of Deacon Minott. During the summer Dr. Lord and William Willard joined the garrison. Several children were born in the fort, but the first child born within the limits of the town of Putney is supposed to have been Aaron, son of Philip Alexander. His birth took place before the fort was built, and there is a tradition that Col. Josiah Willard, in commemoration of the event, presented to the boy a hundred acres of land, situated about half a mile east of Westmoreland bridge. The father

* The son was afterward General George Aldrich. He died at Westmoreland, N. H., in the year 1807.

70 HISTORY OF EASTERN VERMONT. [1755.

of Capt. Daniel How and the father of Harrison Wheeler died in the fort. Both were buried in the graveyard in Westmoreland on the other side of the river. Religious services were for a long time observed among the occupants of the fort, and there the Rev. Andrew Gardner, who had previously been chaplain and surgeon at Fort Dummer, preached nearly three years. The Great Meadow, at this time, was not more than half cleared, and its noble forests of yellow pine, with here and there a white pine or a white oak, presented an appearance which is seldom to be met with at the present period, in any part of the state. Col. Josiah Willard, who owned the Meadow, gave the use of the land as a consideration for building the fort and defending it during the war. The land was portioned out to each family, and the inhabitants were accustomed to work on their farms in company that they might be better prepared to assist one another in the event of a surprise by the enemy. There was no open attack upon the fort during the French war, although the shouts of the Indians were often heard in its vicinity in the night season. On one occasion they laid an ambush at the north end of the Meadow. But the settlers who were at work on an adjacent island, were so fortunate as to discover the signs of their presence, and avoided them by passing down the river in a course different from that by which they had come.*

The expeditions which were planned by Gen. Braddock, in conjunction with the Colonial Governors, against Fort Du Quesne, Niagara, and Crown Point, at the beginning of this year, served to a certain extent to defend the frontiers from the incursions of the enemy. Major Ephraim Williams, who during the year 1754 had taken charge of the western line of forts in Massachusetts, was appointed to the command of a regiment in the latter expedition. Capt. Isaac Wyman succeeded him as commander of Fort Massachusetts. Simultaneous with these extensive operations, measures were taken by Massachusetts to render more effectual the defence of her borders. Garrisons were strengthened, new levies of soldiers made, the people in exposed towns were required to go armed when attending public worship, and it was made the duty of the militia officers to see that this order was observed.†

* MS. Historical Sermons, preached at Putney on Fast Day, 1825, by Rev. E. D. Andrews.

† "The monthly pay of the troops on the frontiers, established by the govern‑

1755.] PARTISAN CORPS AND RANGERS. 71

But the feature which characterized in a peculiar manner the warfare of this year, was the system introduced in the conduct and management Of the partisan corps. The government of Massachusetts had offered a large bounty for every "Indian killed or captured," and to gain this reward, did these ranging parties engage in what were commonly known at the time as "scalping designs." Their field of operation extended from the Connecticut to the Hudson, and from the Massachusetts cordon to the borders of Black river, in Vermont. Each company consisted of not less than thirty men, and of none but such as were able-bodied and capable of the greatest endurance. Sometimes they marched in a body on one route, and again in two or three divisions on different routes, or as ordered by their officers. The commissioned officers kept a journal of each day's proceedings, which was returned at the close of the march, to the commander-in-chief of the forces, after having been sworn to before the Governor of Massachusetts, or one of his Majesty's justices of the peace. No bounty was given until the captured Indians, or the scalps of those killed, were delivered at Boston to persons appointed to receive them.

Compared with the life of the ranger, that of the frontier settler was merely the training school in hardship and endurance. In the ranging corps were perfected lessons, the rudiments of which are at the present day but seldom taught; and the partisan soldier of the last century, though unskilled in the science of warfare, was an equal match for the resolute Indian, whose birthright was an habituation to daring deeds and wasting fatigue. The duties of the rangers were "to scour the woods, and ascertain the force and position of the enemy; to discover and prevent the effect of his ambuscades, and to ambush him in turn; to acquire information of his movements by making prisoners of his sentinels; and to clear the way for the advance of the regular troops." In marching, flankers preceded the main body, and their system of tactics was embodied in the quickness with which, at a given signal, they could form in file,

ment of Massachusetts, June 11th, 1755, was as follows. Marching forces: Captain, £4 16s.; Lieutenant, £3 4s.; Sergeant, £1 14s.; Corporal or Private, £1 6s. 8d. Garrison forces: Captain, £4; Lieutenant, £3; Sergeant, £1 10s.; Corporal £1 8s.; Drummer, £1 8s.; Centinel, £1 4s.; Armourer at the westward, £3." — Hoyt's Indian Wars, p. 267.

In addition to the regularly established garrisons, guards were stationed at Greenfield, Charlemont, Southampton, Huntstown, Colrain, and Falltown, to protect the inhabitants while gathering their crops.

72 HISTORY OF EASTERN VERMONT. [1755.

either single or otherwise, as occasion demanded. In fighting, if the enemy was Indian, they adopted his mode of warfare, and were not inferior to him in artifice or finesse. To the use of all such weapons as were likely to be employed against them they were well accustomed, and their antagonist, whoever he might be, was sure to find in them warriors whom he might hate, but could not despise. As marksmen none surpassed them. With a sensitiveness to sound, approximating to that of instinct, they could detect the sly approach of the foe, or could mark with an accuracy almost beyond belief, the place of his concealment. Their route was for the most part through a country thickly wooded, now over jagged hills and steep mountains, and anon, across foaming rivers or gravelly-bedded brooks.

When an Indian track was discovered, a favorable point was chosen in its course, and there was formed an ambuscade, where the partisans would lie in wait day after day for the approach of the enemy. Nor were mountains, rivers, and foes, the only obstacles with which they were forced to contend. Loaded with provisions for a month's march, carrying a musket heavier by far than that of a more modern make, with ammunition and appurtenances correspondent; thus equipped, with the burden of a porter, did they do the duty of a soldier. At night, the place of their encampment was always chosen with the utmost circumspection, and guards were ever on the alert to prevent a surprise. Were it summer, the ground sufficed for a bed, the clear sky or the outspreading branches of some giant oak for a canopy. Were it winter, at the close of a weary march, performed on snowshoes, a few gathered twigs pointed the couch made hard by necessity, and a rude hut served as a miserable shelter from the inclemency of the weather. Were the night very dark and cold, and no fear of discovery entertained, gathered around the blazing brush heap, they enjoyed a kind of satisfaction in watching the towering of its bright, forked flame, relieved by the dark background of the black forest; or encircling it in slumber, dreamed that their heads were in Greenland, and their feet in Vesuvius. If a comrade were sick, the canteen, or what herbs the forest afforded, were usually the only medicines obtainable; and were he unable to proceed, a journey on a litter to the place whence his company started, or to the point of their destination, with the exposure consequent thereupon, was not always a certain warrant of recovery, or the most gentle method of alleviating pain. But the great object was unattained, so long as they did not

1755.] THE PARTISAN SOLDIER. 73

return with a string of scalps, or a retinue of captives. When success attended their efforts, the officers and soldiers shared alike in the bounty paid, and strove to obtain equal proportions of the praise and glory. The partisans of the valley of the Connecticut were mostly from Massachusetts, Connecticut, and New Hampshire. Some of them had borne for many years the barbarities of the Indian, and were determined to hunt him like a beast, in his own native woods. Not a few had seen father and mother tomahawked and scalped before their very eyes; and some, after spending their youth as captives in the wigwam, had returned, bringing with them a knowledge of the Indian modes of warfare, and a burning desire to exert that knowledge for the destruction of their teachers. To men in this situation, a bounty, such as was offered by the government of Massachusetts, was sufficient to change thought into action, and it did not require the eye of a prophet to foresee the result. Great were the dangers they encountered, arduous the labor they performed, preeminent the services they rendered, and yet the partisan soldier has seldom been mentioned but with stigma, and his occupation rarely named but with abuse. This may be due, in some part, to the deviation from the usages of civilized warfare, which was sanctioned by the use of the scalping knife. Still the impartial reader should bear in mind the circumstances and the times which are under review. He should remember the barbarity of the enemy, the principles of natural justice, or the law of retaliation, the emergencies which were constantly arising, and the necessity which compelled the partisan to fight the Indian on his own terms. Let these considerations be indulged, and the rendering of a juster verdict in future, will show that discrimination has been allowed to take the place too long held by prejudice and scorn.*

Although the greatest precautions had been taken to render the frontiers secure against the enemy, yet the year 1755 bore on its record as large a share of disasters as any which had preceded it. Early in June, a party of Indians attacked a number of persons, who were at work in a meadow in the upper part of Charlemont, Massachusetts, near Rice's fort. Capt. Rice and Phineas Arms were killed, and Titus King and Asa Rice, a lad, were captured, and taken to Canada, by the way of Crown

* Reminiscences of the French War, Concord, 1831; pp. 4, 5. "Rules for the Ranging Service," in the Journals of Major Robert Rogers, London, 1765; pp. 60-70. Hoyt's Indian Wars, pp. 266-268.

74 HISTORY OF EASTERN VERMONT. [1755.

Point. King was afterward carried to France, thence to England, whence he at length returned to Northampton, his native place. An account of some of the depredations which were made at this period in New Hampshire, is given by Hoyt, in the following paragraph: "In the month of June, a man and boy were captured at New Hopkinton, but immediately after retaken by a scouting party. The same month an attack was made on a fort at Keene, commanded by Capt. Sims; but the enemy, after some vigorous fighting, were driven off. On their retreat they killed many cattle, burned several houses, and captured Benjamin Twichel. At Walpole they killed Daniel Twichel, and another man, by the name of Flynt." On the 17th of August, at noon, the Indians in large numbers attempted to waylay Col. Benjamin Bellows of Walpole, and a party of thirty men, while returning from their labor. Failing in this undertaking, they attacked the fort of John Kilburn, "situated near Cold river, about two miles from the present centre of the town of Walpole, on the road to Bellows Falls, the exact spot being said to be just where two apple trees, very visible on the east of the way-side, now bear the fruits of peace." It was bravely defended by the owner and his son, John Peak and his son, and several women, who finally compelled the enemy to retire with considerable loss. Peak was mortally wounded in the assault.*

On the 27th of June,† the most disastrous affair that occurred during the season on Connecticut river, took place at Bridgman's Fort, on Vernon meadow, a short distance below Fort Dummer. On the spot where the original fort stood, which was burned by the Indians in 1747, another of the same name had been erected soon after, and being strongly picketed, was considered as secure as any garrison in the vicinity. It was situated on low ground, near elevated land, from which an easy view of its construction and arrangements might be had. From the manner in which the attack was planned, and from the strategy therein displayed, it is supposed that the Indians, availing themselves of the opportunity afforded by the high ground, had previously viewed the place, and by listening at the gate, had discovered the signal by which admittance was gained to

* Hoyt's Indian Wars, pp. 266-269. A full account of this fight is given in Appendix E.

† Some writers have named July 27th, as the day on which this event occurred. Contemporaneous MSS. corroborate the date given in the text.

1755.] CAPTURE OF BRIDGMAN'S FORT. 75

the fort. On the morning of the day in which the attack was made. Caleb How, Hilkiah Grout, Benjamin Gaffield, and two lads, the sons of How, left the fort and went to work in a cornfield, lying near the bank of the river. Returning a little before sunset, they were fired upon by a party of about a dozen Indians, from an ambush near the path. How, who was on horseback with his two sons, received a shot in the thigh, which brought him to the ground. The Indians, on seeing him fall, rushed up, and after piercing him with their spears, scalped him, and leaving him for dead, took his two sons prisoners. Gaffield was drowned in attempting to cross the river, but Grout fortunately escaped.

The families of the sufferers who were in the fort, had heard the firing but were ignorant of its cause. Anxiously awaiting the return of their companions, they heard in the dusk of evening a rapping at the gate, and the tread of feet without. Supposing by the signal which was given that they were to receive friends, they too hastily opened the gate, and to their surprise and anguish, admitted enemies. The three families, consisting of Mrs. Jemima How and her children, Mary and Submit Phips, William, Moses, Squire and Caleb How, and a babe six months old; Mrs. Submit Grout and her children, Hilkiah, Asa, and Martha, and Mrs. Gaffield with her daughter Eunice, fourteen in all, were made prisoners. After plundering and firing the place, the Indians proceeded about a mile and a half and encamped for the night in the woods. The next day they set out, with their prisoners for Crown Point, and after nine days' travel reached Lake Champlain. Here the Indians took their canoes, and soon after, the whole party arrived at the place of destination. After remaining at Crown Point about a week, they proceeded down the lake to St. Johns, and ended their march at St. Francis on the river St. Lawrence. Mrs. How, after a series of adventures, was finally redeemed with three of her children, through the intervention of Col. Peter Schuyler, Major, afterwards Gen. Israel Putnam and other gentlemen, who had become interested for her welfare on account of the peculiarity of her sufferings and the patience with which she had borne them. Of the other children, the youngest died, another was given to Governor de Vaudreuil of Canada, and the two remaining ones, who were daughters, were placed in a convent in that province. One of these was afterwards carried to France, where she married a Frenchman named Cron Lewis, and the other was subsequently redeemed

76 HISTORY OF EASTERN VERMONT. [1755.

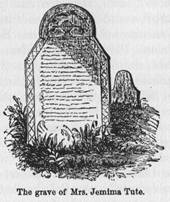

by Mrs. How, who made a journey to Canada for the express purpose of procuring her release. Mrs. How afterwards became the wife of Amos Tute, who was for several years one of the coroners of Cumberland county. She was buried in Vernon, and her tombstone epitomizes her varied life and exploits, in these words.

Mrs Jemima Tute

Successively Relict of Messrs

William Phipps, Caleb Howe & Amos Tute

The two first were killed by the Indians

Phipps July 5th 1743

Howe June 29th 1755

When Howe was killed, she & her Children

Then seven in number

Were carried into Captivity

The oldest a Daughter went to France

And was married to a French Gentleman

The youngest was torn from her Breast

And perished with Hunger

By the aid of some benevolent Gentn

And her own personal Heroism

She recovered the rest

She had two by her last Husband

Outlived both him & them

And died March 7th 1805 aged 82

Having passed thro more vicissitudes

And endured more hardships

Than any of her cotemporaries

No more can Savage Foes annoy

Nor aught her wide spread Fame Destroy*

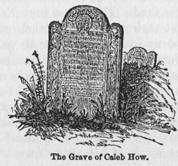

On the morning after the attack on Bridgman's Fort, a party of men found Caleb How still alive, but mortally wounded. He was conveyed to Hinsdale's Fort, on the opposite side of

* A more detailed account of the adventures and sufferings of Mrs. Howe, who has been called the "Fair Captive," may be found in Belknap's Hist. N. H. iii. 370-388, and in the "Life of General Putnam" in Humphrey's Works, pp. 276— 279.

1755.] ATTACK AT HINSDALE'S FORT. 77

the river, where he soon after expired. He was buried about half a mile from the fort, in the middle of a large field, and a stone erected to his memory is still standing, inscribed with this record :—

In Memory of Mr

Caleb How a very

Kind Companion who

Was Killed by the Indeans

June the 27th

1755. in the 32 year

Of his age. his Wise M"

Jemima How With 7

Children taken Captive

at the Same time.

At the close of three years' captivity, Mrs. Gaffield was ransomed and went to England. The fate of her daughter, Eunice, is uncertain. On the 9th of October, 1758, a petition, signed Zadok Hawks, was presented to the General Court of Massachusetts, praying them to use their influence to obtain the release of Mrs. Grout, the petitioner's sister. At that time, she and her daughter were residing with the French near Montreal, and her two sons were with the Indians at St. Francis. It is probable that their release was not long delayed, as one of the sons a few years later was a resident of Cumberland county.

But this was not the last of the incursions of the enemy. On the 22d of July, at about nine o'clock in the morning, a party of Indians attacked four of the soldiers of Hinsdale's Fort, and three of the settlers residing there, as they were cutting poles for the purpose of picketing the garrison. At the time of the attack they were not more than a hundred rods distant from the fort. Four men were on guard, and three were on the team. They had drawn only one stick when the enemy fired upon them, and having got between them and the fort endeavored to keep them from reaching it. Of the soldiers, John Hardiclay* was killed and scalped on the spot. His body was terribly mangled, both breasts being cut off and the heart laid open. Jonathan Colby was captured, and the two others, Heath

* In the letter of Col. Ebenezer Hinsdell, this name is written Hardway. — N. H. Hist. Coll., v. 254.

78 HISTORY OF EASTERN VERMONT. [1755.

and Quimby, escaped to the fort. Of the settlers, John Alexander was killed and scalped, and Amasa Wright and his surviving companion, whose name is not recorded, saved themselves by flight. An alarm was immediately sounded, and the "Great Gun" at Fort Dummer, on the opposite side of the river, was fired. Thirty men from Northfield answered the summons, but their assistance availed only in burying the dead, for the enemy had gone too far to warrant a pursuit. A week previous to this occurrence the Indians burned an outhouse with its contents, situated about six miles above West river, and during the whole summer hostile bands scattered in every direction among the settlements, were watching for opportunities to plunder and destroy. Information of these transactions was sent to Governor Wentworth by Col. Ebenezer Hinsdell, and the closing words of his letter, "we are loath to tarry here merely to be killed," convey in strong terms, a knowledge of the danger which encircled the settlers, and of the incompetency of their forces to afford protection.

Although the governor was willing and anxious to furnish the requisite aid, the New Hampshire Assembly were unwilling to render the least. Application was then made to the Massachusetts Legislature, and Nathan Willard, the commander at Fort Dummer, in a memorial presented in the month of August, described the situation of that post. He stated that the enemy were continually lurking in the woods around and near the fort; that during the past summer nineteen persons, living within two miles of it, had been killed or captivated;" that it was impossible to succor them by reason of the insufficiency of the garrison, which numbered only five men on pay, and that in case of an attack there was no reason why the enemy should not be perfectly successful. In view of these representations, the Legislature directed Capt. Willard to add six men to his present force, to serve until the first of October following. Similar assistance was granted to other garrisons on the frontiers.

The expedition against Crown Point, which had been planned during the spring and summer, was consummated in the fall of this year. The unwearied efforts of General, afterwards Sir William Johnson, to whom the command had been given, though attended with success, were not rewarded with the conquest of the desired station; and the victory of the 8th of September, which defeated the Baron Dieskau and his French and Indian forces, though it served to cheer the spirits of the Eng‑

1755.] THE SUPPORT OF FORT DUMMER. 79

lish in America, was purchased by the loss of some of the best men in the colonies. Of this number was Col. Ephraim Williams, who was shot through the head as he was leading on his regiment in the conflict. His death was universally regretted by his countrymen. His exertions, during a service of many years on the frontier, had won him the esteem and admiration which is due to virtue and valor; and the endowment which he made by his will for establishing the college which bears his name, has kept his memory green in the hearts of succeeding generations, and added to his renown as a warrior the praises of scholars and philanthropists.*

As has been previously stated, Fort Dummer, although situated without the borders of Massachusetts, had been long supported by that province. The Board of Trade had, on the 3d of August, 1749, declared it proper and just, that New Hampshire should reimburse Massachusetts for its maintenance; yet no attention had been given to this advice, and Massachusetts had continued as before to support a garrison at that station. In order to obtain payment for their services, the Council of Massachusetts, "in confidence of his Majesty's goodness and justice," appointed a committee on the 29th of May, 1752, consisting of Samuel Watts, John Wheelwright, and Thomas Hutchinson, who, with a committee from the House, were ordered to take such steps as they should deem necessary to accomplish this object. On the 4th of June, a few days after these appointments were made, the Council, by the advice of their committee, directed Josiah Willard, the Secretary of the province, to write to Mr. Bollan, the agent for Massachusetts in England, in order to learn what course should be pursued with the Board of Trade. Letters were sent on the 25th, but no answer being received, the Secretary, on the 27th of December, 1753, again wrote for instructions. In the latter communication, be stated that Massachusetts had defended the lands west of Connecticut river, for one hundred years past, at an expense probably of £100,000 sterling; that at one of the best forts in the government, standing about twenty-five miles east of Hudson river,† she had kept a garrison of forty men during the war, and had retained men in pay ever since the peace; that she had been long expecting a reimbursement of the charge for supporting Fort Dummer, and defending the other parts of the

* Hoyt's Indian Wars, pp. 271-282.

† Fort Massachusetts.

80 HISTORY OF EASTERN VERMONT. [1755.

frontier of "what is now called New Hampshire;" and that the order of his Majesty in Council in 1744 was conditional, either that Massachusetts should be reimbursed her charges, or that the fort with a proper district of land contiguous should be assigned her. Referring more particularly to that order, the Secretary remarked in conclusion, that the Fort and a few miles of country around it, so far from being an adequate compensation for the expense the province had incurred, were so much the contrary, that she would rather esteem them a burden, as thereby she would not only lose all the past expenses, but be subjected also to a constant future charge. On the 12th of August, 1755, the subject was again discussed before the Council of Massachusetts, and Thomas Hutchinson and William Brattle, with such persons as the House might add, were chosen "to prepare the draft of a memorial and petition to his Majesty, therein giving a full representation" of the affair, and praying for a speedy reimbursement of the charges which had been paid by the province. Thus did Massachusetts from year to year repeat her attempts to obtain what was due her for her services and expenditures. But her efforts were foiled by the vigilance of the New Hampshire agents, and her object rendered more and more unattainable by delay.*

* Various MSS. Mass. Council Records, xxi. 316.