The History of Caroline County, Maryland, From Its Beginning

An Old Time Maryland School (1838)

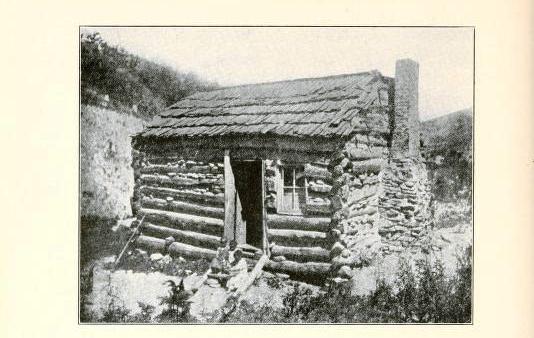

At last with a gathering group of expectant children, and youth of from five to twenty-one years of age, we stood before the open door of the new school house. Not that the word new describes the house; very far from it; but the school was new. The school-master was a new arrival in the neighborhood, and the house was newly and for the first time used for so noble a purpose. Will the reader believe it? The house was really a deserted negro cabin, that stood by the highway side, near Townsend's Cross Roads, three miles from Denton, the county town. For an area of twenty-five square miles between that town and the Delaware line, this was the only school, and this was started by a private subscription managed by my father. The Maryland law, at that time, liberally provided that if the people of a neighborhood would subscribe for the tuition of twelve scholars at five dollars each, then the State would furnish a like amount for the education of the same number of "charity scholars." There was no public provisions for school houses, and whether there was house or school, depended altogether upon the character of the population that, amid rural mutations, might happen to gather in any given neighborhood.

This new school and every school in that region for several years, was in a rented house. This particular house was built of logs, the interstices being filled with clay to keep out wind and rain. It was eighteen or twenty feet square, and abut eight feet to the eaves; with a door front and back, each opening outwards. Midway between the doors and the north end where stood the chimney, at a convenient height, part of the log was sawed out, the aperture being filled with a three-light hanging window, which, as occasion required, could be propped up for ventilation.

Where the chimney stood was an aperture six feet wide and four feet high, into which the stone and mud walls of the fireplace were built to a height above where the blaze of the great log fire would usually reach; and above that pint the flue was made of logs and sticks, liberally daubed within of clay. At the south end of the house, in order to adapt it to its use as a literary institution, almost an entire log had been removed. This aperture was covered by a wide board, fastened by hinges to the log above, and secured to that below by staple and hook. Like the sash before mentioned, this board was propped up to admit needed light and fresh air. Just below this aperture was the writing desk, extending across the room against the wall. Here, alternately, the girls and boys made pot hooks and hangers with their goose quill pens, after the pattern set by the teacher; and finally graduated to the distinguished accomplishment of being able to draw a note of hand or receipt for ten dollars, good and lawful money of the United States of America, and to affix thereto their own seal, written signatures. The teacher "set the copies" during the noon hour; but made and mended pens at all hours, when they happened to be presented for that purpose. Hence the name still so commonly applied to the pocketknife. It was not unusual to see the teacher dividing his time and attention between a page of Comly's spelling book, where some sweating pupil was painfully struggling with the problems of orthography, and the quill he was slitting and whittling, meanwhile stealing an occasional moment for a furtive glance about the schoolroom, to see that there was no pinching, or pin-sticking, or snickering behind books or slates going on among the unruly urchins.

In addition to the so-called writing desk, the furniture of this schoolroom consisted of a desk and chair for the teacher, and three or four slab benches across the end of the room, next to the writing desk. In cold weather a bench was set near the great fire-place, and was occupied by alternate platoons of the shivering scholars to thaw themselves out. Three formidable hickory rods, of varying size and length, adapted to the sex and size of the culprits; and a pretty, little, red maple switch, suited to the esthetic tastes and tender sensibilities of the smaller urchins, completed the outfit. The entire curriculum of our school was covered by the three cabalistic letters, R., R., R., understood to represent the three great sciences, Readin', Ritin' and 'Rithmetic. The three G's, Grammer, Geography and Geometry, had then scarcely been dreamed of as ever possible to be taught in a country school. It was not until several years after--not indeed until the renowned Chinquapin schoolhouse had been built, over a mile away, on the road to Punch Hall, that we ever heard of such a study as English Grammar or Geography. The primer, or rather a primer-for it mattered not what it was, so long as there were A, B, C's in it-was the textbook most in demand at Mr. Marshall's log cabin school. REV. ROBERT W. TODD, D. D.