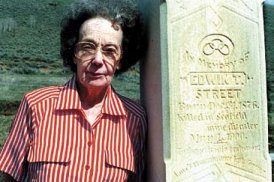

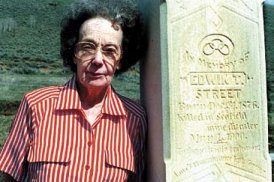

Melbi Erkkila's maternal grandfather Edwin Street, was among those who were killed in Utah's worst mining disaster. At least 200 men died when the Winter Quarters mine blew up in 1900. (Brent Israelsen/The Salt Lake Tribune.)

Melbi Erkkila's maternal grandfather Edwin Street, was among those who were killed in Utah's worst mining disaster. At least 200 men died when the Winter Quarters mine blew up in 1900. (Brent Israelsen/The Salt Lake Tribune.)

BY BRENT ISRAELSEN, THE SALT LAKE TRIBUNE

Melbi Erkkila's maternal grandfather Edwin Street, was among those who were killed in Utah's worst mining disaster. At least 200 men died when the Winter Quarters mine blew up in 1900. (Brent Israelsen/The Salt Lake Tribune.)

Melbi Erkkila's maternal grandfather Edwin Street, was among those who were killed in Utah's worst mining disaster. At least 200 men died when the Winter Quarters mine blew up in 1900. (Brent Israelsen/The Salt Lake Tribune.)

|

SCOFIELD -- On a hill overlooking this near-deserted mining town and a large reservoir sits one of Utah's most unusual cemeteries.

Among the tombstones and headstones lie rows of weathered wooden grave markers, about four dozen total. Almost all have splintered into several pieces. Some have fallen to the ground.

The names of the deceased are, for the most part, illegible. But the date they died is easy to read, and is common to each grave: May 1, 1900. That was the day the nearby Winter Quarters Mine blew up, killing at least 200 men.

It was the worst single loss of life in Utah history and one of the five worst mining disasters in U.S. history.

Although the 100th anniversary is nearly a year away, a small group of Scofield residents and state historians is working overtime to commemorate the event, put together a more accurate account of what occurred, and memorialize those who died.

Their effort is called "A Day of Commemoration and Rededication," and it is being led by Woody and Ann Carter, who run a bed-and-breakfast in Scofield. The project just recently has begun to gain momentum, with the Utah Historical Society, the Carbon County Historical Society and the Helper Mining Museum, to name a few, pledging support. "There is a lot of interest in this. We felt it needed to be recognized," said Ann Carter, whose grandfather helped in the futile rescue effort.

For the Carters, one of the first priorities is installing new wooden markers next to or in place of the old ones in Scofield Cemetery.

"As you see these dilapidated wooden markers, you feel [the victims] deserve something better," said Woody Carter as he walked through the cemetery, which became the final resting place for about half of the mine-disaster victims.

The Carters have persuaded the United Mine Workers of America union in Price to buy wood for new grave markers that will be proportionately similar to the original ones. They cannot be precisely alike because wood widths are cut to different standards than wood 100 years ago.

One of the biggest challenges to making the new markers, however, will be accurately recovering the names from the old wood.

Looking closely from various angles, Woody Carter tried to decipher the name from one of the markers: Kangus? Or Kangas?

"I can't be sure," he said.

To be sure, the Carters will consult cemetery sexton records and other written accounts. They also have enlisted a Navy photographer in San Diego, who has agreed to use digital imagery to read names on old markers.

"There may be a lot of names we just can't identify," Ann Carter said.

In addition to installing new, legible markers, the Carters plan to organize various community groups to rehabilitate the cemetery, which needs new landscaping and masonry work on the entrance columns.

"We've got our work cut out for us this summer," said Woody Carter.

Craig Fuller, of the Utah State Historical Society, also has a tough job ahead. He must coordinate research into what really happened on that fateful May Day.

Of particular concern is compiling a precise list of who died in the disaster.

"There are still some discrepancies on the exact number of men who were lost," said Fuller, who is poring through journals, newspapers, genealogical records and any other record he can find about the disaster.

Accounts of the number of victims have varied between 200 and 246, but some Finnish historians believe the number was as high as 350.

The Finnish are particularly interested because about 60 Finns were among the dead.

"It devastated the Finnish community in Utah," said Fuller, noting the entire Utah Finnish population at the time was only about 300 people.

One Finnish family named Louma lost eight sons and grandsons. The parents and grandparents didn't speak English.

"So what do you do? You are isolated, your breadwinners are all killed. It was a tremendous economic and social impact on them."

Adding insult to the Finns' loss was an unsubstantiated rumor that it was a Finn who caused the explosion, Fuller said.

May 1, 1900, was supposed to have been a happy event for the people of Pleasant Valley, a high-country valley in Carbon County that included the mining communities of Scofield, Clear Creek and Winter Quarters.

Valley residents were planning a big May Day celebration that night, with music, dancing and food from the many ethnic groups -- Greeks, Italian, Scandinavians and Welsh -- that worked the mines.

But the holiday was no occasion for a day off work, and an estimated 300-plus men, ages 14 and older, headed for the mines at daybreak.

About 10:15 a.m., an explosion reverberated through the valley. At first, most residents believed the noise to be cannon fire or fireworks, part of the the day's festivities.

Within a few minutes, though, they saw billows of gray smoke and heard the frantic screams of victims and witnesses.

It is believed that blasting powder used to loosen chunks of coal from the seams ignited coal dust in the No. 4 mine in Winter Quarters, sparking an explosion and inferno.

Carbon County historian Irene O'Driscoll captured the drama in an account published in 1948. "The miners were confined with no chance of escape, caught like rats in a trap. No hope to recover anyone alive, no hope to ever look upon the living faces of those entombed," O'Driscoll wrote.

The explosion threw one miner several hundred feet across a canyon. The miner was impaled on a tree and suffered a cracked skull, but survived.

Poisonous gases from the blast spread quickly to the No. 1 mine, killing additional miners there. It took 20 minutes for the air to clear enough for rescuers to reach the nearest victims.

"Hope had been entertained that some of the men, especially in No. 1, would be found alive, but the farther the rescuers went, the more apparent became the magnitude of the disaster.

Men were piled in heaps, burned beyond recognition."

Some men were found clutching their tools, indicating instant death. Others were found to have died while crawling to escape smoke and fire.

For the next five days, Pleasant Valley was the antithesis of its name as rescuers pulled bodies from the mines, wrapped them in sheets and placed them into pine coffins, shipped by train from as far away as Denver.

"My God, it is awful," wrote a Salt Lake City reporter covering the story. "Whole families are wiped out and the women do nothing but shriek and wring their hands day and night."

Besides decimating a sizable portion of laborers, the Winter Quarters Mine Disaster created at least 107 widows and left some 270 children without fathers. Nearly every home in Pleasant Valley was affected.

The last child of a Winter Quarters victim died earlier this decade. (update)The next closest living links to the disaster are grandchildren who never knew their grandfathers.

One is Melba Erkkila. Her maternal grandfather, Edwin Street, was among the victims.

Erkkila might have lost her paternal grandfather, too, had his wife not "had a premonition that morning and wouldn't let him go to work," she said.

It is stories like Erkkila's that Fuller and the Carters are trying to preserve and share with a public largely unaware of the tragic story that is part of Scofield's mining heritage.

This newspaper article was written by (Brent Israelsen/The Salt Lake Tribune. on Monday, May 31, 1999. After this article was written the following information was received by Gary Ungricht.

My paternal grandmother, Manilla Dewey Farish, is the last surviving child of one of the victims of the Scofield Mine Disaster. She is 101 years old! Her father, Robert Farish, died in the Scofield Mine Disaster, along with his older brother, Thomas Farish, and Thomas Farish Jr., who was one of the boys who died in the explosion.

Manilla was born on July 9, 1898. Thus , she was nearly two years old when her father perished in the explosion. Her mother, Mary Evans Farish, was left a widow with six children to raise. Her father, Robert Farish, was originally born in Ohio, and her mother was born in Wales. The six children of Robert Farish and Mary Evans were: Robert, Fannie, Hazel, Margaret, Manilla and William.

Manilla says that her father, Robert Farish, would have survived the explosion, if resuscitative measures would have been performed on him, because, she states that his heart was still beating when he was removed from the mine. He was overcome with the afterdamp gas and stopped breathing.

Robert's older brother, Thomas, exited the mine after the explosion. When he realized that his son, Thomas Farish, Jr. , did not come out of the mine, he went back inside to rescue him. Tragically, the son was found on his father's back, as his father tried, in vain, to carry him out of the mine. Both were overcome by the afterdamp gas and perished.

Thanks to Gary Ungricht for this update.

Sun Advocate

by Joan Hunt and Winn Wendell

The early morning stillness of Pleasant Valley was broken by the miners, especially those of Welsh descent, singing as they left for work on May 1, 1900. Spring had finally come to the valley and the harsh winter that had helped give Winter Quarters its name had all but disappeared.

On the minds of many that morning was the evening's celebration to open the new Odd Fellows Hall. In addition it was Dewey Day in commemoration of Admiral Dewey's naval victory over the Spanish in the Manila Harbor. Instead of a celebration that evening, 200 miners would be dead, or near death's door, and the towns of Winter Quarters and Scofield would be in mourning.

Riding with the men was William Parmley, mine foreman, whose brother was Bishop Thomas J. Parmley, mine superintendent.

The men, who were paid by tonnage rates instead of hourly, and supplied their own tools and blasting powder, found their working areas. Some started work in No. 1 which had a portal almost level with the town of Winter Quarters while others reported to No. 4 located on an incline that opened out high above the ravine where the town was built.

After a few hours work, Thomas Bell, who was working in No. 1. decided to go home. He was waiting for the next car to come along when his partner, Thomas Farrish remarked. "You might as well go on and walk out, that car isn't coming for half an hour."

Bell did walk out and had gone half way down the hill when the explosion came. Less than two hours later, he was bringing out Farrish's body.

The explosion occurred a half mile inside No. 4. The force was so powerful, it completely leveled a shack that stood outside and tore out the motors and drums for the mine cars. John Wilson, a driver who was at the mouth of the mine was knocked 820 feet down the ravine with a crushed skull and splinter impaled in his stomach.

The rescue part of 20 men, led by Thomas Parmley, tried to get to No. 4 through No. 1 but were driven back by the after-damp or black-damp (the gaseous air that is left in the mine when all the oxygen has been displayed by fire or explosion.)

The party then charged up the hill while the towns people began to pour out in the streets. Smoke was coming out of the mouth of No. 4 and the opening was partially blocked by fallen timbers. It took the rescue crew 20 minutes of concentrated efforts to clear an opening into the mine.

While the crew was clearing the entrance, other rescuers found Wilson on the hillside and the engineer, who would have been in the demolished shack at the time of the explosion if he hadn't been down the incline replacing a derailed car. The engineer suffered only minor injuries.

Another man, who assisted in pushing the loaded trip over the knuckles, was found with his foot crushed, shoulder dislocated and other severe injuries. An assistant helper with a broken jaw and crushed head and a miner who had a broken arm and a leg and internal injuries were found near the mine mouth. The injured were taken to homes for care.

Once the crew could enter the mine, canvas for battices to the portal (air corriders along the mine shaft) were brought. The first man found inside the mine was Harry Belterson, who was badly burned, he passed away that night. nearby was Willian Boweter, who was found alive. Belterson and Boweter were the only survivers found in No. 4.

As the rescuers cleared out each section, the bodies were carried to the mouth of the mine and piled in heaps. There weren't enough men left in Winter Quarters to haul the dead down to the town.

In Winter Quarters the company store employees brought out the store's supply of blankets and pillows for the wounded, not realizing there would be few survivors.

Miners from nearby Clear Creek soon arrived to help bring the bodies down the steep hill from No. 4 to the barn across the ravine. As each body was brought down, wives, children and relatives of the men rushed forward calling out names. Soon the air, which was once filled with singing, resounded with screams of women as they saw what was left of their husbands.

The rescue party, now reinforced, passed from No. 4 to No. 1. The first victims they came upon were Thomas Livsey and his son, William, both badly burned. Here the crews piled the men upon the mine cars, sometimes 12 high. The dead from No. 1 was taken in the boarding house, where, at one time, 66 were laid out ready to be washed.

As soon as the bodies were washed and identified, they were either carried to the school house or meeting house where undertakers arrived at that night and began embalming the bodies.

In No. 1, the after-damp claimed many victims with most men dying of suffocation. Others were buried under tons of dirt and debris. Residents felt the men in No. 1 were taken by surprise and may have thought the explosion was set off to celebrate Dewey Day. Some of the bodies were found with their tools still clutched in their hands, and one man, who had sat down to fill his pipe, was found with the filled pipe still in his hand.

Down in the town, Miss Daisey Harrom, a professional nurse from Salt Lake, was in Winter Quarters for a visit, ran an infirmary for the injured until a train load of doctors sent from Salt Lake by the company arrived.

It was determined that two men escaped from No. 4 unassisted while 103 made their way out of No. 1. The bodies of the unlucky ones were brought out of the mine by rescue teams composed of men from Castle Gate, Clear Creek, Sunnyside and local miners.

The bodies from No. 4 were washed on May 2 and taken down to lie with the men from No. 1 at the meeting house. That same day a special train left Winter Quarters taking A. Wilson, Harry Taylor, William Boweter and John Wilson to St. Mark's Hospital in Salt Lake for treatment. There John Wilson had a steel plate inserted into his head.

Coffins also started to roll into the town. The entire supply of coffins in the Wasatch front was sent to Winter Quarters, and one shipment from Denver helped to supply the need.

Thursday, two days after the disaster, a work force of 130 plus 75 volunteers from Provo started digging graves in a section of the Scofield cemetery. One hundred and fourteen were buried there Friday with Apostles George Teasdale, Heber J. Grant and Reed Smoot of the LDS Church performing the services. The graves were covered at 4 p.m.

While funeral services were being prepared in Scofield, the regular train left Winter Quarters Thursday, carrying nine bodies including three bound for Helper.

Shortly after the regular train left, engine No. 128 pulled out of Scofield with 51 coffins. Two were left at Thistle to be transferred to the Sanpete branch while 11, including Daniel and John Pittman, were left at Springville; six, at Provo; two, in American Fork; one, in Lehi; eight, in Salt Lake; ten, in Ogden; and 11 in Coalville. Each coffin was decorated with flowers sent to Winter Quarters in nine coaches by Salt Lake City resident.

Apparently 114 were buried in Scofield, 69 buried in other parts of Utah, and 12 buried outside the state. The death total reached 200 in August when the 200th victim died and was buried.

The company's manager, William G. Sharp, cancelled all the debts of the victims' families at the company store, a total of $8,000, and paid a $500 death benefit compensation to each family. it was estimated that 113 widows were left after the disaster with 306 children left fatherless.

On May 5 Utah Governor Wells called for the people in the state to contribute to a relief fund and over $110,000 was collected, but the amount given to the families never reached that mark, and many widows left the area with the onset of winter still awaiting some allotment from the funds.

On May 3, Carbon County Attorney L.O. Hoffman, traveled to Scofield to set up an inquest on the body of John Hunter, one of the mine victims. William Hirst, Jurstice of the Peace, acted as coroner.

During the inquest, Andrew Smith gave his explanation of the cause of the explosion. He said Hunter, a miner in No. 4, was killed during an explosion caused by a heavy shot igniting the dust. (At this time it was the custom to blast while the men were still in the mine.)

The state mine inspector, Gomer Thomas said the cause could have been a heavy shot of loose giant powder or loose powder exploding. "The giant powder went off, caught the dust, and exploded it, being in the end nothing but a dust explosion. I went to a place where it was claimed they had powder stowed away and the place showed that the explosion had started here and showed further by the action of the explosion and by the body that was found there, that it was burned more than the other bodies which we found."

He also suggested the coal dust may have added to the explosion and suggested the company keep the dust watered down for safety purposes in the future.

Today only one structure remains in Winter Quarters while the portal to No. 4 is caved in. There is no marker here of the disaster or in tribute to the men who died but a mile down the valley in the graveyard where 115 of the 200 who died May Day, 1900, are buried.

Time is taking away their names from the wooden markers but the wood planks thrusting from the ground are still a reminder of one of this nation's greatest underground mining catastrophies.

This story was prepared by Joan Hunt and Winn Wendell with information supplied by nuerous publications an interview with Thomas Biggs Jr. of Scofield.)

In weeks to come, the history of Winter Quarters and its short span of life will be presented along with the story of the Calico Railroad.