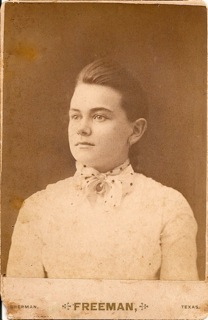

Autobiography of

Kittie Lanham Oakes

INTRODUCTION BY ELAINE OAKES :

Kittie Lanham was born July 16,

1894.

I have combined several documents that my Grandmother

Kittie left.

The originals were partly handwritten and partly typed on poor quality

paper and had deteriorated badly. Some of the material was

repetitious

and some

was fragmentary. None of it was really

complete. Because

they are interesting hints about other stories, I included the

fragments

but put them in brackets. I have added a very little from my

memory

of her stories.

Grandmother was a great storyteller, and it is hard to

say what

really happened and what was just a good story she had read somewhere

and

adopted.

The earlier versions had different names for several

people and

she probably didn't remember most of them by the time she wrote this,

sixty-some

years after the events. I believe most of the ordinary

things, and

most of the stories of mischief she and her sister got

into.

She claims that Sister was wild but from what she said about her own

behavior

she was pretty wild for those days, too. These days they

would be

considered normal to rather tame.

I was born, under a lucky star, I

think, in Grayson County, Texas

in a village so small I cannot find it on my map and it may not even

exist

today. Both my grandfathers were Confederate Veterans and

both were

early settlers in Texas because, as they told me, Reconstruction Days

were

so difficult in South Carolina and Mississippi. They felt

they would

be far better off in new territory and both bought cheap land in

Grayson

County in 1870, within six months of each other. I was born

there so

some of my remembrances are tales they told me as a child.

Grandfather Weems moved his family

from Mississippi to a farm about

four miles west of Sherman and Grandfather Lanham, from Edgefield,

South

Carolina to one about the same distance east. Both lived in

log cabins

in the beginning.

LANHAM FAMILY

My paternal grandfather was Col.

R.G. Lanham. He served with

General Lee in Virginia, and while there he met and married Caroline

Elizabeth

Harrison. I never met her as she died before my father and

mother

were married. The old Daguerreotype picture

and some bits and pieces

of jewelry are all I remember of her, but she left two sons, my father

Tom and Wiley, his younger brother. Papa said that I looked

very much

like her, and he also told me that she was

related to the two Harrison Presidents

and kin to Pocahontas but since then I do not remember, if I ever knew,

the names of either of her parents.

Grandfather must have loved her

very much for he did not remarry

for a long time - until I was about 8 or 9 years old. And

much later,

I found a small notebook among his things with sweet, sentimental poems

he had written to her. I have a lovely heavy taffeta dress,

handmade

with tiny stitches, that she wore when she went to meet her new

husband's

family in Edgefield South Carolina Grandfather Lanham's full

name was Robert

Glover Lanham. My father's name was Thomas Walter

and his brother

was Wiley Harrison. Uncle Wiley never married.

Although one

of Grandpa's sisters traced the family records and had them printed in

a small booklet; my actual first hand knowledge of the Lanham genealogy

is skimpy. My aunt traced the family history back to about

1800 when

Solomon Lanham settled in Maryland not far from Washington,

DC. My

great-grandfather moved to Edgefield, South Carolina and my father was

born

there. My father, Thomas Walter Lanham, was born in

Edgefield, South

Carolina and went to Texas as a small boy in 1870 or 1871. He

grew

up near Sherman and became a schoolteacher. He attended

college in

Sherman but did

not graduate, though he taught

school most of his life and was truly

a bookish type. He was a very good small town school

superintendent.

My father had one younger brother,

Wiley Harrison. He had

a strange and tragic accident, never explained. At the age of

about

21, he was a law student in college at Sherman and was considered to

have

a brilliant future. But one night he rode home, returning

from town.

When his horse came home without him, Grandfather became alarmed and

went

to look for him.

He found his son lying beside the road, unconscious.

Uncle Wiley

was an excellent horseman and it was most unlikely that his horse had

thrown

him. The road was not rocky nor hard packed and the fracture

in his

skull was high enough and jagged enough that no plausible idea was

found

to account for the injury. He was unconscious for weeks and

doctors trepanned his skull to remove

pressure. He was desperately

ill for weeks and the Sherman paper even printed his

obituary. This

he showed me along with two buttons of bone taken from his scull.

He did regain his health but never fully

recovered mentally, was

subject to occasional violent fits of temper. My mother was

always

able to calm him more easily than anyone.

WEEMS FAMILY

My mother's father, James Madison

Weems, was born in Mississippi,

and I still have his old family Bible giving the names and dates of all

his brothers and sisters. Tradition gives the first Weems in

this

country as living in Virginia near the small town of Wakefield where

George

Washington was born. My Uncle Mat had a friend, also named

Weems, who

had traced the family line back to the Wymss Castle in Scotland but the

actual family history has breaks in it, though appearances and

characteristics

indicate kinship back down the history.

Thomas Weems was the first American ancestor of our branch; he lived

in Pennsylvania but married Eleanor Jacoby in New Jersey on 6 Nov 1728.

He moved to Virginia and his descendants to Abbeville District, South Carolina. She,

or one like her, is still around if rather the worse for wear. Her

dress is different, though. I'm not sure if this was James Madison Weems

Jr. or Sr.

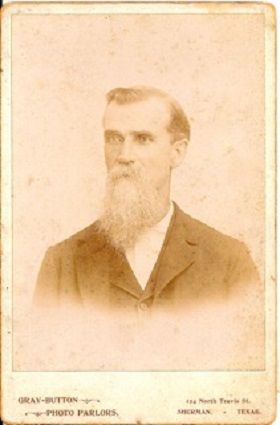

James Madison

Weems, Sr.

(1846 - 1916)

grandfather of Kittie Lanham

(Photograph contributed by Carolyn A. Rogers)

Digging back into memories to see

what one can recall presents problems.

I think, because many children are brought up hearing anecdotes telling

of their early behavior, it is difficult for a person to separate what

they actually do remember from what they may have heard related to them

of early happenings in their infancy. I doubt that many can

draw

a line of distinction with accuracy.

The first place that I am sure I

definitely remember is the house

where I was born. That home belonged to my grandparents and

since

they moved from that small village before I was four years old,

incidents

that happened there are rather unrelated to

any sequence of events. In my

mind's eye, I can see part of that house 'though I cannot recall the

number

of rooms or their arrangement. I know that it was large

enough to

have an upstairs, and that there were two

porches and that it was painted an ugly,

dingy yellow. The front porch had a fancy balustrade around

it, ant

there was a sort of fretwork under the eaves, much more elaborate than

modern taste suggests.

The house was set in a large yard, and

there were several trees

for shade where I could play. Grandpa hung a rope swing for

me from

one of the low branches. And the yard was fenced.

That is about

all I can stretch my memory to cover.

Why the house is less distinct in

my mind than the gin I do not

know. But for some reason, the fact that Grandpa Weems ran

the cotton

gin, and certain incidents that occurred in connection with the

operation

of the gin are more impressed on my memory. I do not know why, but such

is the fact. Ginning season in that part of Texas was a strenuous time

for the manager. The gin ran all night, wagons piled high with the

white

fluff filled the gin yard waiting for their turn. And I

remember

watching these, the horses and mules and the tired farmers. They were

sometimes

so exhausted from the long days in the picking fields that they

stretched

out on top of their loads to snatch the sleep they missed.

They often

did their barn yard chores by lantern light in order to be in the

fields

picking their cotton at the first faint

light of morning.

I loved to see the wagons with high

sideboards move up in orderly

line. To see the huge pipe pulled into position so it could

suck

up the white load into the tearing pulling teeth of the

rollers.

Once I remember seeing a man's hat sucked from his head as he pulled

the

suction pipe into position, and another time, a stone about the size of

a man's fist was drawn into the machinery to damage it and cause a

shut-down.

Time was lost for repairs, then rollers began to turn again and thick,

white felted cotton was folded and pressed into bales and tied with

metal

straps. Perhaps I remember so much of this because I knew

that Grandpa

was working too hard. Often he could not leave even long

enough to

walk across the road for his meals.

Tiny though I was, I could carry a small pail of cold

buttermilk

when Grandmother or Mama took his plate of food to him. And

there

was dusty lint hanging from every weed or tree in the whole gin yard.

Big

black-and-white Dan was the dog member of the family and I think he was

a mutt but mostly of the Newfoundland breed. Grandpa often

said Dan

was such a good, brave watchdog that he saved the wages of a night

watchman

at the gin. He was devoted to me and when any man came to the

house,

Dan always placed himself between that man and Sister and me.

Once

when Mama had been away for sometime, and came up the front walk in her

best dress, an elaborate white organdy with

loads of frilly ruffles, Dan met

her halfway down the walk and she did not see him in time. He

stood

erect on his hind legs, and was taller than she, then he gently put his

arms around her neck and kissed

her. Unfortunately, he did not realize

that the rain the night before had left the feathers along his legs wet

and muddy.

Ironing that white dress took hours but Mama just

laughed and seemed

pleased that Dan was so glad to see her.

Mama had two brothers only a

little older than she and for this

weekend, the whole family was together.

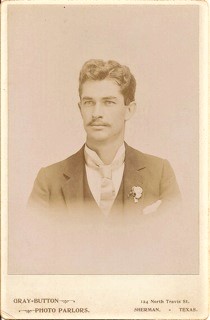

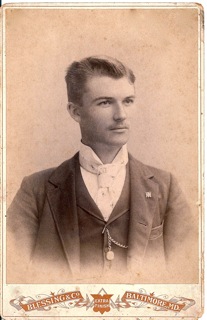

Harvey Weems |

Dr. James Madison Weems, Jr. |

Annie Lou Weems Lanham |

I don't remember what this

celebration was for, but it was something special. Uncle Mat

made

the ice cream. He set the big

freezer on a table on the back porch and turned the crank.

I adored both my uncles, and no small girl was ever petted

more.

But both uncles loved to tease me, Uncle Mat in particular.

That

was how I got the shock

of my young life. It was a warm, no! HOT!

summer day

in Texas and the ice in the freezer melted fast. When

the salty water began to overflow from the wooden bucket of the

freezer,

Uncle Mat set the freezer in a big dishpan.

After several minutes of vigorous turning the crank,

the cream was frozen. Then Uncle Mat set it out of the pan

and wrapped

it in feed sacks and left it on the table to ripen. He pushed

the

pan full of icy saltwater back a little way under the table.

His

job was done and he turned his attention to me. He was

playfully

reciting to me the old rhyme about "The old bumble bee came out of the

barn, and he had his bagpipe under his arm, and he went

z-z-z-z!"

He had a sort of tune to the jingle and when he reached the z-z-z-z, he

tickled my ribs. I backed away, dodging,

and sat down in that icy pan of water. A violent

shock and the first in my young life, I guess! I

howled! The

rest of the family saw only the finny side.

Later, that same afternoon, some young friends dropped

in for the

ice cream and cake. That was when I gave Uncle Mat his shock

in return.

He took his special girl out to the settee on the front porch so they

could

eat their cream together in privacy but I

followed them. Of course,

after the icy wetting I had that morning, I had to have fresh

clothing

from the skin out, and as it happened Mama had made me new underwear of

which I was very proud.

I hunted Uncle Mat up to tell him about that, "I got

new drawers

on, Uncle Mat! Have you got new drawers? Mine have

lace on

them, too. Uncle Mat, do your drawers have lace on them?"

Both Uncle Mat and his young lady were terribly

embarrassed.

So was Mama! I was hustled back inside and given a lecture on the

subject

of what not to talk about.

Operating that gin was hard work,

long hours, and a great deal of

responsibility for Grandpa but he made many friends among the farmers

and

having been a farmer previously, he knew their problems and could talk

to

them. Some of his friends put his name up and he was popular

enough

to be elected County Commissioner. Then he moved his home to

the

county seat town.

CHRISTMAS IN THE WEEMS HOME

His next home was a neat little

gray cottage and I could almost

draw a blueprint of that place, it is so firmly fixed in my

memory.

The whole family gathered there for the first Christmas that I can

remember.

It was a traditional Christmas, only we did not have a tree at

home.

I was told that Santa Claus would come down the chimney if I hung up my

stocking, however, since there was no fireplace, only a big black

heating

stove with a six or seven inch pipe, I could not quite take in the idea

without a few questions.

James Madison Weems Sr. home at Celina

James Madison Weems Sr. with wife Kittie, Catherine Red Weems, and

his daughter Annie Lou Lanham Weems with her two daughters Carrie Lee

Lanham (Autry) and Kittie Lanham (Oakes)

As for the Christmas tree, Uncle Buddy came to take me

to that.

Since our family was only visiting from out of town, Mama explained

that

I need not expect Santa Claus to have anything for me on that tree, but

that my presents would surely appear the

next morning in my stocking.

After assuring Mama that I just wanted to see the gorgeous, big tree

with

its bright decorations, and that I would not be disappointed, she let

me

go with him. Imagine my surprise when my name was called the

same

as the other children! Santa, himself, brought me a little

packet

tied up in bright ribbon. I was proud as could be, with a

lovely

box of four tiny perfumes, all different "flavors".

That Christmas Eve night I was so excited, and my

small black cotton

stocking did not seem nearly big enough to hold the doll I wanted, so I

borrowed one from Grandmother. Then I worried for fear Santa

would

not know it was mine so I wrote a letter to him telling him about the

exchange

in hose. I was not more than five but I had been reading and

writing

more than a year. I carefully pinned the letter to the long

stocking

and hung it on a chair beside the stove just before kissing everybody

"goodnight"

and saying my "Now, I lay me."

At Grandpa's home, I do not remember ever having a

tree. There

were always a few decorations, a mistletoe wreath with red ribbon bow

on

the front door, and some other bunches hung around the parlor (never

called

a "living

room then") and in the dining room. One of

Grandmother's sons

or Papa saw that she had flowers, usually a vase of red and white

carnations.

But the only tree we saw was at the church. A tall cedar with

many

candles carefully placed and strings of popcorn and cranberries;

sometimes

tinsel strings sparkled among little brown paper bags of candy for the

children, and striped peppermint candy canes, and a few of the lighter

weight unbreakable toys.

Next morning early, I found a small China doll in the

top of my

stocking. She was so beautifully dressed in soft red wool

that I now know

Grandmother must have spent many hours making that lace trimmed

petticoat

and tiny ruffled drawers with baby-sized buttons

and buttonholes. Beside

my stocking, there was a tiny iron cook stove almost an exact replica

of

the one in our kitchen, and the miniature pots and pans to go with

it.

I was so proud! I still have that doll.

The memories of that Christmas are still

vivid. It was wonderful,

the family happiness, the laughter, the jokes and gentle

teasing.

Before the hearty breakfast, with every one of us around the long

table,

Grandpa conducted family worship. He read the story of the

Baby Jesus

from the family Bible, said a short, earnest prayer, then served our

plates.

Grandpa was a very devout man, a steward in the

church, and he held

family prayers every night just before retiring.

After breakfast, Grandmother and Mama began preparing

the elaborate

Christmas dinner, stuffing and baking the turkey, getting vegetables

ready,

and all the things that could not have been prepared earlier.

Coconut

white cake, spice cake, and a big platter full of fancy cookies had

been

prepared during the week but several fruit cakes had been ripening,

occasionally

sprinkled with whiskey, for more than two months. Uncle Mat

and Grandpa

beat up eggnog and set it to ripen on the back porch. Each of

the

three of us had a sip, and my opinion as to its quality was

gravely considered,

even though they both were perfectly aware that was

my very first taste of the delectable stuff. It was later

served

with some of the fruitcake to any guests who might drop in.

The China doll I received that Christmas was not my

first love for

I remember Nora. She was a rag doll and I do not remember

just when

she was acquired, but I must have been very young, probably about

three.

Mama made

this doll but it was all hand made and hand-painted

with some of

Mama's artist oils. I think she even made the pattern the

doll was

cut from for I have never seen another so well shaped. It had

a nicely

rounded head, well-shaped nose, and seams were well hidden under the

beautifully

painted baby face, which looked so much more like a real baby than the

China doll. Nora even wore some of Sister's outgrown baby

clothes.

She was the only doll, of the many later ones I had, that I ever wanted

to take to sleep with me, I loved her so.

LIVING WITH THE KANE FAMILY

Papa was a country schoolteacher

and moved about from one place

to another quite often. The first school that I remember

about was

probably about twenty miles from where Grandpa and Grandmother

lived.

It was in a farm

community and our little family could find no house

available for

the teacher's family. We were fortunate that one of the

members of

the school board took us in to board in his home.

We became members of the Kane family which was already

rather large

consisting of three grown sons, one of them away at college, two grown

daughters, another almost grown, and the baby of the family only a year

older that I. She and I were great playmates.

The Kane home was large with a big attic

where Lorena and I could

find the most amazing costumes for dressing up like ladies.

There

were several storage trunks of garments that had long gone out of

style,

picture hats with enormous plumes, veils and

wraps. That was a wonderful

place to play, especially on rainy days. We could spend hours

there

without interfering with any of the grown-up projects.

Mr. Grayson Kane was a very devout

man, a well-to-do farmer and

popular in that section of the county. It was the custom some

time

during the summer for an itinerant preacher to come into the community

with a tent and hold

about 10 days camp meeting. Once or twice

the meeting was

held in Mr. Kane's big pasture, but after a few years, the church

managed

to scrape up enough cash to buy a small tract of land on which they

expected

to build a

church. Until this church was erected, a

brush arbor was put

up. Supports of four or five inch logs were set in the ground and a

framework

of lighter poles nailed across their tops. Then brush was

piled on

top enough to provide shade and even some protection from a light

shower.

At one end of the arbor, a platform was set up, and borrowed chairs

provided

seats for the choir. A crude shelf was set up at the front of

the

platform to hold the preacher's Bible, though after reading a few

verses,

it was rarely referred to. Some one in the community loaned

an organ;

the lodge provided

flare torches, and the camp meeting was off to a good start.

If the preacher was well known, sometimes families came for several

miles

in their big farm wagons. Mattresses and quilts were brought,

as

well as food for several days. Such gatherings of relatives

and friends

might provide their annual get-together, unless a funeral might

intervene

when the clans would always gather.

Ordinarily, the Kane family attended the camp meetings

with reasonable

regularity since they lived only about three miles from the meeting

grounds.

But one summer, Mrs. Kane decided she was going to camp. Mr.

Kane

put up the objection that he could not stay at night because of his

live

stock. They had to be attended to night and morning, but in

the end,

he agreed to fit up one of his wagons for camping. One of the

older

boys could stay with the family and Mr. Kane and the hired hand Rufus

would

go to meetings during the days, always returning to the farm to do the

chores and sleep there.

Rufus was a drifter who had never been

exposed to the hellfire and

brimstone some of those country preachers could dispense.

Neither

was he overly gifted with gumption, though he could and did fulfill his

farm duties fairly well under the close supervision Mr. Kane gave

him.

Mr. Kane was a little surprised when Rufus indicated that he wanted to

attend some of the services but readily gave his permission, with the

proviso

that Rufus was to return at night with Mr. Kane to help with the

chores.

After seeing the preacher get himself well warmed up to his sermon,

and seeing several shouting women, and

mourners converted, the combined

effect of these things made considerable impression on Rufus and he

went

down to the mourner's bench. But though many of the believers

prayed

with Rufus,

and he returned to the bench for prayers several

times, Rufus was

still unconvicted. He was still struggling trying to think

things

out one night when he and Mr. Kane started for home.

The meeting was expected to close the next day so Mr.

Kane had left

his gentle farm team of horses with his family, just in case they

wanted

to come home before he returned. On this night, he was

driving a

team of young mules to his wagon. They were not yet

thoroughly trained

for their duties, but were excellent plow animals. No noise

followed

the plow, but the wagon made sounds to them, running over some of the

rocks

in the road, empty and rattling along.

Rufus, still under the spell of the

preacher, was struggling in

his soul, trying to pray salvation through, and asked Mr. Kane for

help.

Mr. Kane quoted scriptural verses in answer to all the questions and

was

sincerely concerned about his hand's welfare. The mules were

trotting

along under perfect control, the summer moon overhead, the peaceful

night,

and Rufus praying softly.

About half way between the Kane home and the arbor,

there was a

long sloping hill leading down toward the Kane gate. Just as

the

wagon reached the top of this hill, Rufus stood up shouting.

"I've got it! Hallelujah! Glory

be, I've got religion,

Mr. Kane! I'm goin' to Heaven, now!" The startled mules'

first leap

threw Rufus over the back of the wagon seat where he fell into the bed

of the wagon, still shouting. Mr. Kane braced himself, trying

to

control those frightened mules in their headlong race down the hill,

expecting

every second for one of the wheels to strike a rock large enough to

overturn

the careening wagon.

Rufus pulled himself up on his knees,

yelling at the top of his

voice. Mr. Kane was sawing on the heavy reins, trying

desperately

to bring his team under control.

"Shut up, Rufus!, he ordered. "For pity

sake, quiet down!" But

Rufus paid no heed. "Hallelujah, I'm a-gonna see Glory!"

The mules

ran the harder. In desperation, Mr. Kane gathered both reins

into

his left hand, swung himself around on the seat and clouted Rufus right

in the mouth.

"Dammit, you fool! Shut your mouth, or we'll

both be in Heaven,

next minute!" Such an outburst was entirely out of character;

Mr. Kane normally

being a quiet, mild-mannered man, that Rufus was shocked into

silence.

The mules were quickly brought under

control, and the two men reached home

safely and in silence. Neither of them ever mentioned the

incident.

One of the neighbors, however, had just turned his

team off the

main road into his lane. He heard and saw the frantic

run-away and

he repeated the story to the preacher.

The preacher stared at the man thoughtfully, then, "I

take it, Mr.

Brown, you don't drive mules," he said mildly.

When school was over, we went back

to Grandpa's for a visit.

I cried myself sick when Mama gave my rag doll, Nora, to Lorena as a

parting

gift.

Lorena and I, both, had other dolls but Nora was my

favorite.

Mama promised me she would make me another just like it but she never

did.

Strange how a single childish incident sets the pattern or furnishes a

clue to other more important sequences. But from that time

on, I

knew in the depths of my heart that my wishes, my desires, and my

longings

were of minor importance to Mama. I realized then, though I

was very

young, that I could never count on complete fairness from

her. And

I have never understood why my doll should be taken away from me and

given

to some one else over my unwilling protests.

Even after we moved away from that

community, we often went back

on visits as long as we lived in Texas. Lorena and I were

flower

girls when her grandparents celebrated their golden wedding.

In those

days it was a rare couple who lived long enough for that fiftieth year

celebration, since then Texas was not far past pioneering

days. It

had been a hard life for many of them.

Little old, Mrs. Callahan looked very sweet in her

embroidered white

dress, and their sons and daughters bought a lovely gold brooch for her

gift and an elaborately engraved gold-headed cane for Mr.

Callahan.

I even remember

the identical ruffled white dresses Lorena and I wore,

with wide

gold-colored satin sashes. The reception was held in the

Kane's big

living room and banks of goldenrod were everywhere.

UNCLE MAT

While we were with Grandpa and

Grandmother that summer, Uncle Mat

hung up his shingle as a dentist. First, he had studied for

more

than a year under an old dentist who wanted a young partner.

When

he was sure that he wanted

to continue in this profession,

he went away to school in Baltimore

and studied in the dental college there. Later, he became one

of

the best in Texas and with his own practice.

After a couple of years in the East at school, he came

back and

was quite the gay young blade, with his very fashionable tight fitting

trousers, derby hat, and bicycle. He also acquired a

beautiful trotting

horse, a buggy, and various other accessories.

Once, he took me to Denison on his bicycle, a distance

of about

six or seven miles. He had planned to meet some of his young

friends

there. Some of the young women had come in buggies.

But for

that one night, I was thrilled at being his best girl. He

told me

so. He took me for a boat ride on the lake, got a water lily

for

me, and fed me all the popcorn and pink lemonade I could

handle.

I had a wonderful time.

As we were riding home, with me on the handlebars,

much later than

my usual bedtime, his rear tire went flat and that meant we had to walk

for miles. Part of the way was along dark road, and through deserted

streets.

When we

finally did arrive at home, the whole family was up

waiting.

They were astonished that I had walked all that distance, without a

single

whine or whimper. And though it was very late and I was only

about

five, I had not complained of being too sleepy to walk and had never

asked

to be carried.

PAPA'S SECOND SCHOOL

The next school my father taught

was endowed. Part of the

funds for it came from the state, but the building, grounds and house

for

the teacher's home were provided by a very wealthy old doctor as a

memorial

to his only daughter. He had selected about five acres from

the middle

of a huge pasture for the site.

He kept herds of cattle in that pasture and

when some of them were

near our yard fence, Mama was deathly afraid and she would not go into

the yard herself, nor let me go even though we had a good fence of

three

or four strands of barbed wire. She was especially fearful if

some

of those big red bulls began pawing the dust nearby.

The schoolyard was also fenced and there was plenty of

play ground.

Since the doctor was quite an advanced thinker for his day and time, he

had provided space for the children to learn how to plant a garden, set

out a few fruit trees, and make flower beds and hot beds.

The main building was a large, white frame structure,

with two

long rooms separated by a sliding partition so that they could be

thrown

together to provide for a community center. A narrow stage to

provide

for school programs ran along one end, and there was a smaller single

room

for primer classes and the first and second grades. This

building

was about the size of the many one-room schools that dotted the rest of

the county.

Our house was just across the road from the school and

it was constructed

on the same pattern of all the better farm homes in that section. It

had

a hall straight back from the front porch to the kitchen, with a large

room on each side and a stair going up from near the single center

door.

The upstairs plan was identical. There were no closets, no

built-ins,

not even a back porch. The dug well was about thirty feet

from the

kitchen door and that in itself was considered a great convenience, as

the wife on many of the farmsteads in that area sometimes had to carry

water several hundred feet. Our well was about thirty feet

deep and

all the water used we pulled up with rope and pulley. Every

home

had a brass bound cedar bucket set on a wash shelf near the kitchen

door

with a big tin basin and roller towel handy.

We lived at this place several years and

everything I learned about

the people in the community interested me. Some were rugged

individuals.

There was old Doctor Sheperd, who had provided this

school for children

from his tenant families, and many more besides. The greater

number

of pupils walked to school, sometimes several miles. Others

rode

horseback, and one family sent their kids in an old buggy.

When I was about six, Dr. Sheperd vaccinated me for

small pox and

I remember that he asked Mama to be sure to save the scab when it fell

from my arm. He provided a small box filled with sterile

cotton for

her to put it in and he used that scab for many of his patients who

needed

the vaccination but could not afford to pay for serum. He

said I

was such a healthy little animal that my scab would do for several

hundred

inoculations. Nowadays, medical procedure like that is beyond

the

imagination of modern practitioners. I suppose many of the

younger

doctors

have never come in contact with a case of smallpox,

and they certainly

can have little idea of how terrible that dreadful pestilence used to

be.

I have since seen several cases and I know.

Dr. Sheperd was a fine man and I admired him greatly

but I doubt

if he knew much about medicine. He had a fairly good library

and

did considerable reading but I never knew that he attended any medical

seminars or such.

But his team and buggy were familiar over

all the roads round about.

He carried a small black pillbox and from it dispensed calomel and

quinine

as needed. And that was about all, except for a pair of

forceps,

a needle and

gut strings, and his thermometer.

Undoubtedly, his greatest

value to the community was the comfort and sympathy he gave his

patients

along with his pills. They trusted his wisdom, his knowledge

of human

nature and went to him for advice on many

family problems other than health.

After we had been living on Dr.

Sheperd's place for about a year,

Mama and Papa received an invitation to a wedding. Mr. and

Mrs. Kane

were giving their daughter a church wedding, and Mama was asked to take

charge of the affair. Lorena and I were to be flower girls

again.

This was to be the first church wedding I ever attended.

Since we

were about twenty miles from the nearest florist, Mama and some of the

neighbors gathered bushels of honeysuckle vines to decorate the little

chapel. I have no idea how many white tissue paper flowers

they made.

Over the altar, they made and hung a white bell and the church looked

lovely.

After all that elaborate preparation, the poor groom

was so flustered

that he forgot to pick up the bride's bouquet at the railroad

station.

Mama sacrificed all the cosmos in her flowerbed, tied them with a satin

bow, and that made a pretty, ferny armful for the bride to

carry.

WYOMING

That

summer, Papa went to Wyoming to work but I don't know whether it was

harvesting

or ranching, or what. He thought it would be good for his

health

for him to change climate and work in the open for a few

months.

That left Mama alone with two very small

daughters and the nearest

neighbor about half a mile away. Uncle Buddy thought she

would be

much safer if she had a gun for protection so he brought her a nice .32

Smith and Wesson pistol. It was a

good one and Mama was so proud of it.

She took it out in the back yard, set up a mark and began a bit of

practice.

She was already an excellent shot with a rifle or a shotgun but had

never

tried her hand with a pistol.

Our nearest neighbor was a rather odd person who went

by the name

of "Whispering Jack!" When he plowed his fields, he did it by

the

sound of his voice and if the wind was right neighbors in the next

county

knew it.

We could almost set our clock by the time when he

called his daughter

Jane to fetch in the milk cows for the evening milking. He

had been

a cowboy before he settled down to raise his family, and he had been on

many of the

early cattle drives. He took great pride in

his ability as

a rifle and pistol shot. So when he heard Mama shooting, he

came

up to see.

He challenged her and they agreed to a match, using a

small knothole

in the end of a barrel for a mark. Jack was amazed when Mama

out-shot

him badly. He liked Mama and told everybody around how good she

was.

I had seen her shoot the head off a fryer when unexpected company might

drop in for dinner but that was with a twenty-two rifle. This

was

her first try with her new pistol.

I begged to try the pistol, too, after Mama and Mr.

Lynch finished

their match. I was so small that I had to hold the pistol in

both

hands to aim it and it took all the strength of both index fingers to

pull

that trigger.

But even so, I almost hit that

knothole they had used for

their mark. Mama was pleased and promised that when I was older she

would

teach me to shoot, too, but she also gave me a little instruction on

how

dangerous guns were and told me never to touch her gun unless she gave

me permission. During Papa's absence, that gun was laid on a chair at

the

head of her bed every night in easy reach if she should ever need

it.

By day, it was equally available in the top bureau drawer.

Yet, I

knew I must not touch it. And as Sister grew older she was

taught

in the same way. There it

was, in easy reach any time but so far as I know

neither of us ever

disobeyed in that respect. I do not know if such instruction

would

be as effective today with all the 'bang-bang' shows on TV, but I've

always

thought that the great danger in such weapons is not in the gun, but in

the lack of proper training.

Summer that year was unusually hot

and dry. Many wells failed

and ours was so low we wondered if it would hold out. Mama's

garden

parched, and her flowers all dried up. Sister became listless

and

hardly ate. Mama worried

for fear she would get seriously sick. At

last, Mama decided

she had had enough of the loneliness and heat. She would go

to visit

her parents. It was a long hard trip for a woman traveling

alone

with two small children. It meant about ten or twelve hours by horse

and

buggy. But she made plans to set out.

Jane Lynch agreed to feed and water the chickens, the

cow was put

in their pasture with their milk stock. Mama washed and

ironed all

our clothes and packed them in her valise. She prepared a box

of

lunch, stowed a quilt and

pillow in the back of the buggy, hitched Sam up to the

buggy, and

we were ready to travel as soon as the searing afternoon heat began to

lessen.

During the heat wave, the blazing sun had been so hot

Mama feared

it would make us all sick if we drove in the heat of the day.

She

was also afraid of the dark when out alone on the road. But,

she

chose darkness as the lesser of the two evils. She knew just

about

how long it would take to travel that distance with any luck at

all.

But the last thing she put into that buggy was her pistol - just in

case.

What made her most uneasy was the new

Frisco railway line in process

of construction south from the Indian Territory. Mama had no

exact

knowledge of the distance between the road that she must take and the

construction camps along the railway. She

had been hearing some tall tales

about the behavior of some of those rough men working as laborers in

some

of the crews. If she should happen to meet up with stragglers

from

those camps, she meant to protect herself

if she had to.

Just before dark, Mama stopped at a farmhouse to ask

for water.

She drew a bucket of water for Sam and filled a jar with water for us

in

case we asked for a drink during the night. We ate our fried

chicken,

potato salad, buttered bread and cookies with the fresh cool

water.

Before we drove on, Mama spread the quilt and pillow to make as

comfortable

a bed for Sister in the bottom of the buggy as she could. She

knew

Sister would soon be sleepy but she hoped I would stay awake to keep

her

company. She told me she needed me to keep her

awake. During

the long night, she told me wonderful stories, and we both sang all the

songs we knew.

Fortunately, there were no other travelers on the road

that night

after dark. Though it was not really very dark after the moon

came

up. Once, as we were trotting along, Sam suddenly

shied. He

jumped nearly across the road. Some large animal, what it was

we

could not tell, bounded out of some bushes along the fence

row. We

did not know if it was a dog or wolf. It made no sound. It

leaped

easily over a high fence and disappeared.

Mama had been over this stretch

of road and knew there was no farm house

nearby. She believed it must have been a wolf. Some

coyotes

were known to be in that section, but this beast was much too large and

coyotes are not so bold.

Occasionally lobos drifted into that area and Mama

thought we had seen one and surprised him as much as he surprised

us.

She was more startled than frightened for she had her pistol at her

side,

and I was confident she would have shot it if it had turned towards us.

Day was just breaking when we reached Grandpa's

house. After

fixing us a bite to eat, Grandmother put both Mama and me to

bed.

We were both worn out. Sister had slept so well she was fresh

and

lively.

SUMMER AT GRANDPA & GRANDMA'S HOUSE

Sister and I found it very

pleasant to visit here. There was

lots of room for us to play, and shady oaks for coolness.

Grandpa

had a good rope swing in one of them. Back home, in the

middle of

that pasture, there were no shade trees in sight. In our

yard, there

was one small scrubby cedar set near the front porch.

Best of all, there were other children near that we

could play with.

And across the street an old lady had a bright green parrot, which we

enjoyed.

Her cage was usually hung on the wide

veranda. Polly amused

us when she whistled up a pack of dogs. She called and

whistled until

there might be about a dozen dogs on the lawn. She knew each

boy's

special whistle and could imitate it

perfectly. The dogs ran around bewildered,

each trying to find his master. Then she would scream "Git

out!

Go home, you curs!" And the poor deluded pups would slink

off, knowing

they had been fooled again.

We never could understand how Polly could repeat that

performance

so often without those dogs catching on to the trick, but it never

failed

to amuse us.

While at Grandpa's we learned to watch for the tamale

man.

A Mexican with a small pushcart came by each afternoon selling "Hot

tamales!"

He was regular as ice cream vendors are now.

But Mama and Grandmother thought the highly

spiced tamales

were not good for children and rarely let us buy.

The Mexican had used considerable ingenuity

in making his little

pushcart. He set a big lard can in the box rigged up on two discarded

bicycle

wheels. The big lard can was packed all around with newspapers and

partly

filled with hot water. A smaller can filled with the tamales

was

set in the hot water and had a tightly fitting lid placed over

that.

The tamales came out steaming when he forked them out on the plate we

brought

when we were allowed to buy them.

Though she could not have known, Grandmother's colored

girl told

us that those tamales were made from dog meat and that all Mexicans

were

dirty. I knew it wasn't true for Uncle Mat had taken me for a

ride

once and we had passed this Mexican's

house. There was no other Mexican family

in the vicinity and while the place was shabby and run-down, it was

clean.

Ella May just did not like Gonzales but if we bought his tamales, I

noticed

she did not refuse to eat some of our purchases.

Ella May did not like the quaint old Chinaman who

passed almost

every afternoon, either. He was strange, she said, and ate

rats.

He was always dressed the same, long black shirt and no other man wore

the tail out at that time. His black cotton pants were short

enough

that his white socks showed. The only change in his

appearance was

in his headgear. Sometimes, he wore a tiny black pillbox cap

with

his long gray queue dangling down behind, but if he wore his odd straw

hat, he coiled his queue out of sight.

A few small boys sometimes followed him chanting in a

nasal

singsong, "Ching-ching-Chinaman, eats dead rats!" But he

always ignored

them, walking along in quiet dignity. These two were the only

foreigners

I knew as a child. That they were different I

understood. But

both Grandmother and Mama always pointed out that a lady worthy of the

name should treat every person with courtesy. Nice manners were the

mark

of a lady, and that theme was drilled into me most thoroughly from

infancy.

Courtesy and consideration! The two most important words of

all.

Grandpa Weems served in the

Confederate Army and was captured at

the fall of Vicksburg. As I remember his comment on that, the

soldiers

he was with were heavily outnumbered and when they started to retreat,

found a regiment of blacks behind them so they turned and ran back to

surrender

to the whites.

He was imprisoned on an island, Number 10, and many of

the guards

were black, and the prisoners were so starved that some caught and ate

rats.

The Yanks stripped most of the state of food and even before capture he

said much of

the time all he had to eat was

ears of corn right from fields as

they marched.

After he was freed, Grandpa went back home, but

Reconstruction times

in Mississippi were bad. The whole section where he had lived was in

ruins,

no money, no supplies, no horses or mules to work the land or even

seeds

to plant it, impossible taxes, debts,

etc. Indescribable.

On some of the land the freed slaves stayed and they and both my

grandfathers

tried to get along. Since all white men were disenfranchised,

only

carpetbaggers and ignorant blacks were running the government, and much

of the land had been confiscated; it was time to move to Texas.

I remember one of them said that if war could have

been postponed

for as few as ten years, it never would have happened, both because of

the

economic conditions and because of the invention of the cotton

gin.

The other grandfather

said he had to work so hard to make his farm pay even

before the war that he was not sure if he owned the place and the

slaves

or if they owned him.

Then they heard of cheap virgin land in

Texas. So they went

in 1870. It was raw virgin land and it meant long hard labor,

so as

soon as a log house was livable they sent for their families.

I do

not how Grandmother Lanham went to Texas, but I assume she went by boat

with her two small sons and essential household goods to Galveston,

then

by freight wagons to Sherman.

I know that Grandmother Weems made the trip by boat

down the Mississippi

River and across the gulf where Grandpa met her and his

family.

Grandmother Weems' maiden name was Martha Catherine

Red. A

cousin of mine, Inez Bosewell Biggerstaff traced her line to Josiah

McGaw,

a soldier in the Revolutionary War who fought with the Swamp Fox,

Francis

Marion's men in the army near Charleston, South Carolina. At

one

time, her people were quite well to do and lived on a large plantation,

but both her parents died of malaria when she was about

seven. He

uncle, Dr. Red, raised her along with his

own three daughters. They had a French governess

and she was given the customary education for gentle-women of that

period.

She was taught some French, a little music, polite social manners and

beautiful

convent type sewing, nothing very practical for a pioneer's

wife.

Mary Catherine Red Weems

Grandmother's handwork was exquisite and she always

felt that the ability

to "sew a fine seam" was the mark of true gentility. But the

war had wiped

out her family fortune, and it was a long-standing joke that Grandpa

had to

teach her how to cook when they went to Texas. To her credit,

she

did adapt to the rigors of pioneering, but without losing her

polite social ideas of being a LADY. And one of her common

admonitions when I was a child was "Remember, my dear, you should

always

behave like a lady" - or "A little lady would never do that!"

When she spoke of the times she remembered back in

Mississippi,

she often mentioned incidents when she was teaching the young

slaves.

Uncle Red had built a small church on his plantation and Grandmother

called

the young children in to learn to read,

write and figure each morning.

The house servants were well trained. In fact, if

Mammy Lou

had not been devoted, my premature mother, who weighed in at three

pounds

fully dressed in those two long flannel petticoats, wool undershirt,

etc.

would not have lived. She was put to bed in a large roasting pan on the

let-down door of the first big iron cook stove in the county.

And

Mammy Lou faithfully kept the wood fire at the proper temperature for

days

- so Mama was incubated before incubators were invented.

Grandmother

had five children but Mama was the last, and the only girl. Grandmama,

Kittie Weems, wrote the following letter to her sister-in-law after her

brother George Red died.

Sherman, Texas Dec. 6th,

1880

My Dear Mattie

I expect you are looking for a reply to your last

letter so I will

try and

write a few lines tonight if my eyes do not fail

me. I have

been so

busy and it has been so cold and wet that I

thought I would wait until

I got through with

my work before writing. I have quilted five comforts

this winter and am almost through with my

winter sewing. We are

all very well at present. My

health has been better for the last few months.

Well, Mattie I know that you will be very much

surprised when I tell you

that we will move next Monday to the Poor

Farm. Jimmie is appointed

superintendent

of the farm. They pay him four hundred

and sixty ($460)

dollars and feed the family. We

will have a very nice and comfortable home

to live in.

Jimmie will not have to work. The boys

can go to school all

year. This is

why I consented to go. I do not like the

idea of going at

all but-as Jimmie thinks it

best, I will try it this year. I will not

have any thing

to do in the affairs there.

Jimmie is trying to get through with

his corn this week - will make

over thirteen hundred (1300) bushels, he

has not finished his cotton

yet. We have had a month of bad

weather. This is why Jimmie is not

done gathering

his crop. We had rented this place for

another year.

Are you through with your crop, how many

bales of cotton did you make? I hope you

realized a good price. I am glad

that you have nice hogs to kill.

Will you keep the young man that you now

have another year? Tell Herman Aunty

thinks he is a very smart boy to pick so much

cotton. He must be a good boy

and take the place of his Papa as near as

he can, Mattie. You must-try

and cheer up.

Think of your dear little ones, it is hard to

become reconciled

to the loss

of our dear ones. When I think of my

dear brother as he was

when here and then think that I can never

see or hear him again, oh! my heart almost breaks.

But Mattie we all have to die soon or late let us

try and meet him

beyond the skies where there is no

parting. I wish that I

could spend Christmas with you and the

children. I know it will be a sad

time for you

ALL ALONE. Poor children Papa will not

be there to enjoy it

with them-but.

You wished to know all our ages. Pa was

born Apr 27th 1817

died July 23rd 1849. Ma was born

May 25th 1821 and died 1855 Nov 26 -- I

think. Bud was born June 10th

1844. I was born May 26th 1846. Sue was

born Aug 1st 1849 and died Nov 6th 1860 --

Bud lived to be four years older than Pa.

Ours has been a short-lived

family. All gone but me, Oh Mattie

think how lonely I must feel. I

do not expect to live much longer.

My eyes have become exhausted and I will

have to close. Kiss the children

all for Aunty

and tell them to be good children. Write

soon, I am always

so glad to get a letter from you.

Your Affectionate Sister

Kittie

Mama stayed with her parents until almost

time for Papa to come

back home. She wanted to be there when he arrived and she decided that

since the weather had moderated and the heat was not so severe, it

would

now be best to drive back by daylight. The trip was

uneventful and

while we liked to go, we found we also liked to come back to our home.

Papa came in looking so healthy and brown.

He enjoyed his

outdoor work, but he was glad to be back, too. It was always

a busy

time just before the opening of school. So many details, so

much

correspondence, planning and organizing various

projects, he worked harder in those last two

weeks before the start of a term than any other period except the one

opening

day and the closing day.

This year arrangements had been made to have a music

teacher connected

with the school. Miss Grace Kane came to live with us, and

one of

the front rooms was set aside for her piano pupils. Mama did

not

mind cooking for one more and she liked

Miss Grace so much that she was glad to have

her in our home. Since she was a very attractive girl,

naturally,

she had young men coming to see her. One in particular, I

admired

so greatly that I thought could not grow up

fast enough to marry him - and of course,

I didn't but Miss Grace didn't marry him either. A frustrated

romance!

RIDING A HORSE FOR THE FIRST TIME

My first experience with horses

came about this time. Papa

liked to ride Sam and he was a very good saddle horse, though Mama

always

used him in the buggy. Papa had a Mexican saddle with a horn

as large

and round as a saucer. I can

remember he would swing me up behind the saddle,

put Sister in front on that wide saddle horn, and away he would gallop

across

the prairie. It was wonderful.

Once, Papa left home early in the morning to attend to

some business

and he came back about the middle of the afternoon, tired and

hungry.

He filled Sam's watering trough, then asked me if I wanted to ride

around

the yard, while he went in to eat his

dinner. Of course I did, but it

was something I had never tried before. Sam had other ideas

about

that. He wanted to be fed too and started for the

barn. I tugged

at his reins to turn him but he paid me no heed. I barely

managed

to stop him in time to slide off before he dragged me off as he went

into

his stable. But from then on, I wanted to learn to ride and I

loved

horses.

Mother had been an excellent rider and she used to

relate how when

I was only a few months old, she had taken me up in her lap to ride,

sidesaddle,

whenever she visited any of her friends. Grandpa and Papa

used to

boast that she could handle any horse they ever had. She even

drove

Uncle Mat's fine racer hitched to his light training cart and this was

considered quite a feat for a woman. Crockett, a beautiful

blood-bay

animal, was so high spirited as to be a bit fractious. Even

so, Mama

frequently drove him down town on errands. Whenever she did,

some

of Uncle Mat's sporty friends who knew the

horse would jokingly challenge her to a race, but they always

found some excuse to back out of it if she accepted the bid.

Sometimes,

they gave as their excuse that it would not be a fair race since Mama

was

so much lighter than they, which fact was

true. Though their

real reason for not wanting to match a race with her was that they knew

her ability with the reins and her skill in controlling the

animal.

Besides Crockett had a reputation for speed. No young Texan

would

enjoy or willingly accept defeat at the hands of a woman in a trial of

this

sort.

MY LOVE OF READING

So far, I have had only a little

to say about Papa. At a very

early age it was brought home to me that he was terribly disappointed

that

I was a girl instead of the son he had hoped for. Most of the

time,

he ignored me completely. I do remember that on rare

occasions, I

have overheard him boast that I learned to read before I was

four

years old. However, that feat was started on my own

initiative.

Both Papa and Mama loved reading and they frequently

read aloud

by turns to each other. If they buried themselves in separate

books,

I was left to my own resources. Then I would get my Mother

Goose

Rhymes or a primer and

pull my little rocking chair between them, as close as

possible.

If any one would listen, I could repeat any of these books from memory

but if I tried to read them, I sometimes faltered over a single

word.

Then I insisted on being told what that

word was. If either parent

ignored my question, "What's this word?" I simply sat and repeated over

and over "B, d, b, d," until it become so monotonous that one of them

would

finally stop reading long enough to tell me the word I wanted to

know.

I cannot remember learning at all. According to school

standards,

my self-education was not exactly balanced. I read well and

understood

what I read. I knew many words and their meanings, but I was

not

a good speller. I had little interest in numbers and had

never been

taught any arithmetic, but I could count and make change.

I loved reading and by the time I was seven, when

other Texas children

were just starting to school in the primer, I was reading and enjoying

the old "Youth's Companion." I read every text in reading

that Papa

had in his library, and since he was

frequently given complimentary copies of

sets for all the grade in school, that was quite a lot of reading for a

child who had not gone to school at all. I could and read

some newspapers

but since that was before comics reached their present popularity, I

found

little to interest me.

Papa did not want me to be too far advanced in school

and held me

back by putting me in the second grade at the start of my

schooling.

And he never would allow me to be promoted or advanced except at the

end

of the year. I never understood why he deliberately held me

back.

I really do not believe it is best for children to be pushed too fast,

either, but it is hardly fair to force them to work below their

capacity.

PAPA AS SUPERINTENDENT OF SCHOOLS

The first year I started to school

was the year Papa got a larger

school and we moved to the county seat

where he was superintendent of three

schools. This town was about twenty or more miles from where

we had

previously lived and in another county. Papa rented a house

just

across the street from the high school where he would have his classes,

which made it very convenient for him. There was a smaller

grade

school in one corner of the big campus ant that is where I started to

school.

Only the three first grades were in that building.

Our house was not large but it was very comfortable

and it was set

in a fenced yard heavily sodded with Bermuda grass. Papa had

a colored

man who came to keep it nicely cut and it made a wonderful place for

romping

games,

with some of the neighbors' children, and there were

usually several

of them around.

The house had four huge rooms, but the room we used

most was the

cozy dining room, for we loved the big, old stone fireplace, and the

round

dining table served for games as well as for meals. By that

time,

Sister and I could play Flinch, Old Maid and other similar games, but

actual

playing cards were not permitted. Sometimes Mama and Papa had

their

friends, most often other teachers, in for Flinch.

That fireplace was where we gathered on cold winter

evenings.

Sometimes, we shook a wire popper over glowing coals and listened for

the

snappy pops of the corn. Sometimes, we roasted apples and

sweet potatoes

in the hot ashes, and once in a while, when it was

very cold, Mama hung an

iron pot of beans or stew over the fire to simmer for our

supper.

On rare occasions, she even made corn pones in a heavy iron

spider.

Oh, we loved that fireplace!

We lived in this place two years, and it was there

that I had my

first regular schooling and I admit I was much more interested in the

other

children than in my books, which were far too easy to demand my

undivided

attention. Many times, I begged to carry my lunch to school

because

most of the other children did and I wanted to be like the other small

girls I knew. I was sure having my lunch on the school

grounds would

be a picnic and I wanted the whole noon hour for play. But

Mama insisted

that I come home for my lunch and I can remember only once that she

relented.

Our playground had none of the modern

equipment that small folks

find as a matter of course on their playgrounds now. Never

having

seen slides,

acrobatic bars, and such, we did not miss them but

improvised our

own amusements by laying heavy boards across fire-wood logs hauled into

the yard for fuel. Those were our teeter-totters.

And when those

same logs had been sawed into stove lengths, we dragged and piled them

in place to build walls for our play-houses. Maybe we

appreciated

more what we had to make ourselves than little ones who are given

everything

ready-made. I don't know but I think we got double the fun.

When I was promoted to the third grade, I had my first

love affair.

Not an unmixed blessing! The little boy who sat behind me,

dipped

my pigtails into his ink well and whenever he wanted my attention, he

yanked

them, too.

But he also gave me presents. He shared his

gingerbread

with me at recess sometimes; he gave me some of his favorite marbles to

play jacks with; and he brought me my first gift of flowers.

That

was a huge arm full of lilac blossoms, and some way that happens to be

my favorite perfume, to this day.

Another gift that I received while we lived here was

the first and

only gift my father ever gave me personally. It was a small

child's

book of Eskimo stories. I have never understood why he

happened to

bring it back to me after one of his trips, nor why he never gave me

any

other present. I have always believed he rather ignored my presence

because

he never overcame his disappointment that I was not the son he

wanted.

Sister was his favorite and he frequently gave her little

things.

Possibly, this was because she looked so much like him, partly, I

think,

because she was named

for his mother, and partly, also, because she was gayer than

I and she did not draw back into a shell as I did whenever I sensed his

snubs. Shortly before we moved from this town, the whole

family received

a shock that I shall never forget. Sometime very late at

night we

were awakened by pounding steps on our front walk. A man's

voice

was calling Papa urgently. He said he had a wired message

from Papa's

father asking Papa to come immediately, that Grandpapa had shot Papa's

brother. We were horrified and could

not believe what we heard.

While Papa dressed, Mama phoned to find out when the next train

left.

Then Papa thought to phone the telegraph office and have the message

read

to him. It was not true, of course, but what had happened was

bad

enough. The message actually said that Grandpapa had killed a

man,

and that Papa was to let Uncle Wiley know, and both sons were asked to

come at once.

GRANDPA'S GROCERY STORE

Grandpapa owned and operated a small grocery store

with a large

wagon yard in connection at the edge of town. Country people

coming

in to trade frequently drove long distances, too far for their wagons

to

make the round

trip in one day. They would park their rigs

in Grandpapa's

enclosure, stable their teams in his sheds, and buy supplies for

several

months ahead. A few men brought their wives and when they did a bed

usually

was made up in the back of their wagons for

the family to sleep over night unless

they had relatives to visit. Other men came alone and these

had their

choice of sleeping in their wagons or taking a bunk for 25 cents in the

bunkhouse.

If purchases in Grandpapa's store amounted to a

considerable outlay,

there was no charge for these facilities.

Usually everything about the yard was quite

orderly, but occasionally

some rough men would come in on a Saturday night and cause a

disturbance.

On this particular Saturday night, Grandpapa was alone in the place

when

a big, drunken bully came in and began cursing Grandpapa for some

fancied

wrong. The abuse started at the front end of the long

store.

Grandpapa tried to pacify the man but as he talked quietly to him, he

was

backing away from him. A few plain chairs were set out down

the center

aisle for the convenience of customers, and this man picked up one and

was menacing Grandpapa with it. He carried the chair raised

high

over his head, threatening to strike

Grandpapa down. Grandpapa continued

to walk slowly backward, still trying to reason with the man.

He

even appealed to the two other men who had entered the store behind

this

dangerous ruffian. They refused

to have any part of it, knowing how quarrelsome drinking

made this man.

Grandpapa had backed almost the full length of the

store until he

was in reach of a desk where he kept his books and accounts, with

the man still following and becoming more

abusive. When he reached the desk,

Grandpapa pulled open a drawer where he kept his pistol. By

this

time the man was so close, he could reach Grandpapa with a heavy blow

from

the chair.

"Put that chair down!" Grandpapa ordered crisply, as

he brought

the pistol into plain view at his side.

The man swore foully as he lunged forward to bring

the chair down

with all his strength. Grandpapa sidestepped and shot from

the hip.

Grandpapa was a quiet,

mild-mannered, little man with wavy gray

hair and a neatly trimmed beard and he looked very much as many another

Confederate veteran of those times did. He must have been in

his

middle sixties at the time. It still seemed strange to any one who knew

him that even a drunken man could be so foolish, to try to intimidate

one

of General Lee's officers, especially one who

had served four years with

his staff and was still with Lee at Appomattox.

There was no formal trial after this

killing. Grandpapa, with

his two sons, reported to the sheriff the next morning, and answered a

few questions. The man who was killed was notoriously

quarrelsome

and dangerous especially when drinking and even his companions under

oath stated that Grandpapa had ample

justification. Though the

wild Saturday nights in some Texas towns were less frequent than they

had

been previously and the custom of shooting a town up never had the

prevalence

that movies and TV programs would have you

believe, there were plenty of times

when such violent incidents did occur. All the wildness was

not yet

gone.

PROSPER, COLLIN CO., TEXAS

Shortly after that, Papa moved us

to Prosper, another Texas town.

I was then in the fourth grade and far more advanced than some of the

adolescent

boys in my classes, several of whom were grown in size. A few

of

them were so unruly, the school board

thought it wise to employ a man teacher.

The grade school teacher was a character I associated in my mind with

Ichabod

Crane and there certainly were strong physical similarities.

Mr.

Dean was almost bald, tall and angular and

he was fired with a great determination

to drill mental arithmetic into our heads. An excellent idea,

perhaps,

but then, some heads are virtually impenetrable, meaning some of those

larger boys. They were slow in

books but not necessarily dumb for

many of them were already qualified to take a man's place at round-up

time

or harvesting.

Math was not my strongest subject, but I could figure

much more

rapidly than these over-grown boys. In return for a whispered

answer,

I was kept well supplied with apples, candy and chewing gum, sometimes

even Sen-Sen.

Gum and Sen-Sen were contraband

but my Geography was large enough

to provide me with an adequate screen. And if the strong

scent of

the Sen-Sen gave me away, I could always say in all innocence that I

had

been given some at recess.

Come Spring, and these older boys and girls began to

moon around

and to make lovesick calf eyes at one another. It was so

obvious

that love-love-love had struck his older pupils that even Mr. Dean

recognized

the symptoms and decided his best course of

action would be to shuffle the seats.

These young Romeos were much too shy to stand around corners and waylay

the girls of their fancies so they resorted to note writing, an

activity

that was strictly against Mr. Dean's rules of conduct.

Mr. Dean's schoolroom was long and the double desks

were arranged

facing the front with a long aisle between them, and since they were

expected

to need more help with their lessons, the smaller children sat in

smaller

desks closer to the front where teacher's desk was placed. At

the

back of the room the desks were large enough to accommodate grown-ups

and

that is where these older pupils were seated with the girls on one side

ant the boys on the other. The aisle was too wide between the

two

rows of desks to make it safe to pass notes between them, for Mr.

Dean's

desk was placed exactly in the middle where he would have the best

opportunity

to see and intercept anything passed between.

Page

2