The water bucket was

near the door just back of Mr. Dean's desk and we were permitted to get

a drink at any time during the day provided there was no other pupil getting

a drink at the same time. I'll never know why Mr. Dean assigned me to the aisle seat next

to the back. Neither will I ever know how many trips I made to that

water bucket. On each trip I picked up a note to Gertrude from Ed's desk

and passed the answering note to Ed on the way back, but Floyd and Bessie,

John and Lou, also took advantage of my unquenchable thirst.

My first business experience occurred while I was in Mr. Dean's

room. It was common practice for the teachers to present school programs

during the year. Proud parents delighted in watching Bill or Sue

sing or recite a poem, and different classes had group singing. Always,

these programs were well attended for very few recreational opportunities

existed. If there was a need for certain supplies for the school

not provided in the regular budget, these programs helped to raise the money. Admission

charges were always low, but receipts amounted to $75 or $100 at times.

Papa never wanted to take this money to the bank himself. So, when

I was about eight, he called me into his office and showed me how to prepare

a slip for the bank deposit. He gave me the money tied up in his

handkerchief or in a brown paper envelope, and told me to be at the bank

before closing time, and he usually allowed me the barest minimum of time

to make it. The first time, our banker was quite surprised to see

so small a child transacting business in such amounts. I had to stretch

to reach his window and he kindly offered to fill in the slip for me.

But I told him Papa had meant for me to do it myself.

There were a lot of things I learned in that school, most of them

not under Mr. Dean's tutelage. First, I learned how to make stilts

with a wire strung through tin cans, I think I got the idea from some magazine

I read.

But when they saw me walking on my cans, nearly every child in school

did likewise. "Monkey see, Monkey do." But just imagine the clatter

several score of small children can make on a rocky hill. After that idea

caught on, it was not long until the boys were busy making real wooden

stilts for themselves. One of the older boys made a nice pair for

me and these held my feet about two feet above the ground. Some of

the larger boys built theirs five or six feet up and then climbed out of

the lower windows to balance themselves for walking on them. All

of those who had stilts formed a line according to the height of his stilts

and paraded about the schoolyard in a "Crane Brigade." It was a lot of

fun, but only a few of the girls tried it.

LIVING WITH THE JONES FAMILY

[Lightning struck the school building while Flinch was played.

My first cigarette for two bits.]

The last year we were at this place, the school board had some trouble

finding a qualified teacher for the primary rooms and Mama decided she

would go back to teaching. The school building was set at the top

of a long white rock hill. It was a frame building and the road in

front of it was flatteringly called "Main Street" and led into the business

part of town at the bottom of the hill. Just across the road, a family

by the name of Jones moved into a large house from a good farm south of

town. Mr. and Mrs. Jones were rearing a family of nine children, including

the young granddaughter whose mother died at her birth. The two older

children of the family were not at home as the oldest son was married and

the oldest daughter was away at school.

The very happiest two years of my childhood were spent in this home

with motherly Mrs. Jones in charge. Her heart was huge, big enough

to take in our whole family - Papa, Mama, Sister and me - and to treat all

four of us exactly as if we were her own. I shall never know how

she managed to care for the fourteen of us, with no extra help, but

she seemed to have ample time for everything, loving us all, and teaching

us practical things, too. She prepared three bountiful meals each day,

did all the laundry except that the girls were expected to iron their own

garments. She worked a small garden in the back yard, though the

big garden was planted back at the farm. She canned vegetables and

fruit in season, made her own clothing and dressed her four girls nicely.

With all of this strangely enough, she never seemed rushed or flurried.

She had help mornings and evenings from her girls, but during the day they

were all in school.

Her two youngest daughters and the small granddaughter were close

in age to my sister and me. In some homes, there might have been

quarreling and jealousy between us with five girls so very close together

in age, but I cannot remember that any of us ever had more than the tiniest

spat during the two years we were together. When Mrs. Jones assigned

chores to her daughters, such as dish washing or feeding the chickens,

Sister and I were expected to help but to us, it always seemed more of

a lark than work.

As I have said, Mrs. Jones was all heart, and her generosity went

much beyond her own family. Once, I recall, tragedy struck a young

family living nearby. The young father was rushed to an asylum after

becoming suddenly violent and almost succeeding in killing his wife and

baby. After the horrible experience, the little wife went into deep

shock and was unable to care for herself or her child. Mrs. Jones

gathered up the baby and its mother immediately and took them home with

her. They had no claim on her except their desperate need.

For several weeks, she cared for the baby, petted and nursed the mother

until she recovered enough to begin to try to pick up the pieces.

And Mrs. Jones did all this in addition to managing her already over-sized

family.

The Jones farm was a large and prosperous, only four or five miles

out of town. Mr. Jones still did a large part of the farm work himself,

though he had a tenant in the old farm home. There was a nice small

orchard back of the house and to one side a large well-kept garden.

These two supplied much of the food for the family and every year Mrs.

Jones put up great quantities of preserves and jellies, canned goods and

dried vegetables.

She still kept poultry there, ducks, geese, guineas, turkeys, and

chickens, going back often to see that they were properly cared for. I well

remember going to the farm one early spring day when she took Mama with

her to help pluck the geese for their down. The feathers were ripe,

she said, and the geese were beginning to shed them. I don't remember

how many bags of down we picked, but the job of picking looked easy when

Mrs. Jones did it. She sat in a chair, tucked the goose's head between

her knees and plucked at a great rate. When I tried it, my skirts

were too short, and the old gander reached his head around and almost took

a chunk out of the calf of my leg. I had a big, blue bruise for more than

a week but I was determined to do my share, so I borrowed a long skirt to

protect myself and got on with the job. Another time that year, we went

down to the farm to can peaches. The smaller girls and I climbed

trees to pick the fruit because we were light and would not break the branches.

After that job was completed, and Mrs. Jones and Mama were busy peeling

and canning the fruit, I took a notion that I wanted to see a great deal

more of my surroundings than I could see from the ground. There was

a tall windmill between the house and the barn to supply water to both.

It was turning rapidly in the breeze. Up l went, to the very top

and was standing beside the spinning wheel. I don't know who tattled,

but Mama came running out of the kitchen, white as a sheet. If the unpredictable

wind had veered, that wheel would have struck me and knocked me down for

a drop of about thirty or thirty-five feet. Mama called me to come

down at once; and when I had done so, she turned me over her checkered

apron for a spanking I never forgot.

Old Kate was the bay mare that raised most of the Jones children

and she was gentle as could be, but she was fully aware that she had earned

her retirement. Sometimes her patience was a bit short. When

Mr. Jones gave me permission to ride her if I could catch her when she

was loose in the big pasture, I walked miles but she stayed just out of

my reach. Mr. Jones could catch her easily and part of the time,

he kept her in the barn at the back of the lot in town. While she

was there, any one of us five little girls who wanted to ride, could put a rug across her back, bridle

her and ride around town. Usually when this happened, as many kids

as could scrambled on too. She never bucked, but if we wanted more

action out of her than she felt necessary, she just stopped where she was

and shook. That settled the matter.

THE TOWN OF PROSPER

[Riding Steers]

I have not described the town, which was only a few long blocks

down the long, white rock hill. It was probably typical of other

small towns. There was a bank, a post office, a few small stores on each

side of the unpaved street, which was deep in dust in the summer, and knee-deep

in mud in the winter. Boardwalks were built up about two feet above

the ground in front of these stores; and all along the outer edge of these

walks, hitch racks were provided for the teams and horses of customers.

Practically any hour of the day a few saddle horses would be seen, as familiar

to the town merchants as their owners.

The first big snowstorm that I can remember came while we were living

with the Jones family. In that section of Texas, snow that stayed

on the ground was rare. This time there were waist-high drifts all

around the house. Papa, Mama and some of the older boys and girls had a

snow fight in the yard, washing each others faces in the loose snow and

generally having quite a hilarious romp. Sister and I were too small

to get into the scuffle so we stood at the window to watch. I thought

it was grand fun to watch them tumbling around, laughing and squealing, but

Sister began screaming at the top of her voice. Nothing could convince

her that it was all in fun. She threw such a fit that she managed to break

it up in short order.

The snow melted a little during the day, then froze hard and crisp

during the night. Next morning it was just right for sleds but no

child had one.

We improvised and had as much fun, maybe more. A big old dishpan

had been used to water the chickens until one night it froze and the bottom

of the pan swelled and bulged. It was large enough that one child

could sit in it, and a slight push at the top of the hill sent it spinning

and sliding all the way down at a great rate. We picked up speed

as we went. Each of us had a short piece of broom handle to try to

guide our projectile but that was not easy. We took turns, and when

Sister's turn came she was so entranced with the speedy ride she failed

to steer herself and swing out into the middle of Main Street. Instead,

she and the pan hit a rock and veered in toward the stores. She slid directly under some

wild half-broken colts and why she didn't get her brains kicked out was

a wonder. Hers was the last dishpan ride we got. The banker

saw it happen, came out and took the pan away from us, stopping our fun

in a hurry. He not only confiscated our pan but he phoned Mama to

give her a piece of his mind for letting us pull such a dangerous stunt.

Somebody is always ready to tell parents just how to raise their children!

Later that spring, we found another way to use that long hill to our advantage.

Mr. Jones had a young colt he wanted to train to drive and he brought the

colt in from the farm and kept it in the barn at the back of the lot.

He also brought in a very light two-wheeled training cart. The colt

was very skittish and we did know better than to try anything with him.

But that cart! We were certain we could make it useful. As

many kids as could hang on to it piled on. Then, with one child

running in front to hold up the points of the shafts, the gang could ride

all the way down the hill. The long slope coupled with the weight

of the children built up considerable momentum. It was enough to

make those two wheels spin fast. That was great fun until one of

our runners stumbled and fell, dropping the shafts. Those points

dug into the ground, and the cart, children and all, did a complete half

circle into the air and over. Luckily, none of us were hurt.

OUR PET "ANTELOPE"

One pet that we children enjoyed during this period was a young

antelope shipped from New Mexico by Mr. Jones' brother as a pet.

She was immediately named "Vet" but why I don't remember. She was

hardly half-grown when she arrived and was already quite tame. We

loved her at once for she made an exceptionally nice pet. A safe

place was made for her in the barn, but she much preferred to live in the

house with us. She ate from our hands and if we had a snack of bread

and butter, she expected her share, too. If she did not get what

she wanted or if we scolded her, she would throw herself on the floor and

pout like a spoiled child.

When we were outside, she followed us like a puppy and she rarely

ventured beyond the gate, though it was not long until she could easily

clear the fence in a bound. If a strange dog came into view, she

would show her white flag of a tail and two round spots of bristles would

stand conspicuously erect. Anytime she saw a dog, she would snort,

then bound up on the porch. Whoever was nearest when the tiny hooves

clattered on the porch rushed to the door to let her inside the house.

Once when somebody carelessly left the front gate ajar, she ventured

across the road into the schoolyard. A pack of dogs saw her and gave

chase. She was terribly frightened and streaked around the

school building, into our yard, but the dogs were gaining on her and she

came in so fast she could not manage a leap to the porch. She

was forced to circle the house and the dogs were gaining on her.

By that time, I was out with a broom to beat off the dogs, and Sister was

holding the front door wide open for her. Vet was so exhausted she

barely made the leap to the porch, and when the door slammed to behind

her, she dropped to the floor and lay there trembling. It was a close race.

A TEXAS STORM

Texas weather was often unpredictable. One spring day a sudden hailstorm

came up and hailstones as big as hen eggs fell. I have never seen

them so large since, nor so many of them. The wind that accompanied

the hail was so strong and the hail beat against the front door until it

took Mama and Ginnie, the oldest of the Jones girls, both bracing their

weight against the front door to hold it closed against the force of the

storm. It was frightening, the din of the heavy ice pounding against

the walls. The hailstones drifted against the garden fence until

it took three days of warm sun to melt them all. Lou and I took a

big wash tub out to the drift and picked up enough clean hailstones

to freeze ice cream that night for supper and to have some left for ice

tea a couple of days. [Genevieve and Frances and the hail.]

Mama was worried frantic all during the storm because Papa had taken

one of our horses earlier in the day and was away on a business trip.

She had expected him back before noon but something detained him and he

had not returned when the storm struck. Fortunately, he saw it coming

in time to make it to the barn and only one or two of the stones struck

him. He and the pony barely made it to shelter. The barn had

a tin roof and the noise of those chunks of ice falling on it was deafening,

he said. He took the saddle off of Fannie but she refused to go into her stall.

She nuzzled her head under Papa's arm and was so frightened that she stood

there trembling until the storm was over.

Fannie was a beautiful sorrel mare, gentle as a kitten, but very

temperamental. Papa was an excellent rider but while I never saw

Fannie throw him and do not think she ever succeeded in doing so, on several

occasions I have seen her buck him out of the saddle. She was an

expert at sun fishing, could whirl on a dime, but she never tried to fall

backwards.

I rode her sometimes but only when I was sure she was willing.

She had a certain way of snorting, cutting her eyes around in a sneering

manner when I started to saddle her, that warned me I'd better pick a more

suitable time. She never gave me a bad spill but when she was tired

of amusing a child, she would stop, hunch her back in warning. If

the child did not take the warning, she would bounce gently once or twice.

If the child still stayed on, she bucked, easy at first but getting harder

every jump. I learned to crawl down at about the third bounce. I

knew that if Papa could not stay in the saddle when she was in earnest,

I couldn't. Fannie and I had an understanding; I loved her and I

think she loved me, but she would stand for no foolishness. Sometimes

Sister rode her too, but only after I had tried her out to see if Fannie

was agreeable. There was always some hay in our barn, but in one corner,

we girls cleared and swept out a spot to set up housekeeping. It

was a splendid place to play whenever the Texas sun beamed down with all

its heat and there was usually a nice breeze through the big open doors.

And when it was rainy, we would be as noisy as we liked. One rainy day we

were underfoot too much to allow Papa to concentrate on some of his studies

for he was a very bookish man, always absorbed in deep theories.

He wanted us to go out to the barn to play in the hayloft.

"But, Papa, there is a bumblebees' nest right by the side of our

spot!" we protested. He snorted at that idea and said bumblebees always

made their nests in the ground. He even got out one of his textbooks

to prove it. We insisted that we knew they were in the hay but he was not

convinced, unfortunately, for he went out to the barn to throw some hay

down to the horses. He was badly stung.

THE BIRTH OF A NEIGHBOR'S SON

A young couple who lived just behind the Jones' home was expecting

their first child. Mrs. Lord's mother lived so far away that there

was no chance for her to come and be with her daughter during the confinement

and there was no nearby hospital. In those days though, there was

always some woman in the neighborhood, who out of the goodness of her heart,

would volunteer to help out in such cases. Mrs. Jones with Mama's

help and that of a few other neighbors, took over this case. Mrs. Lord's

two-day-old baby was the first tiny infant I had ever seen. I was

not fascinated for I remarked that he looked like a shriveled-up old man

except that he was so red. Mama was shocked at my frankness and gave

me a private lecture later on the subject of tact. Mrs. Lord expected to

nurse her little son as a matter of course. After the third day she

had so much milk that her breasts pained her and began to cake. Mrs.

Jones knew exactly what to do but her remedy was rather jolting to Mama.

Mrs. Jones instructed Mr. Lord to find a young suckling pig for his wife

to raise right along with their son. That little pink porker certainly

looked queer cuddled in her arms while she fed her own baby at the same

time. But it was a very practical solution to the difficulty, as

both the child and the pig were thriving and fattening at a great rate. Once

in a while, Mr. Jones complained about rabbits eating up the garden or

gnawing his fruit trees. These wild creatures were numerous and could

cause a great deal of damage. When the subject came up, Papa and

Mr. Jones decided to go rabbit hunting. They were very successful

and brought back enough rabbits to divide with the neighbors. Nobody

then knew anything about rabbit diseases, but from all appearances, these

were quite healthy and when Mrs. Jones fried them like chicken, they were

equally as delicious. Mr. Jones was quite fond of them and always made the

same remark. "If you don't like rabbit, ain't the gravy good?"

He believed in feeding children all they could possibly hold.

Whenever Mrs. Jones or Mama decided any child had had enough and wanted

to call a halt to that child's gorging, it was his custom to slip an extra

piece under the tablecloth to that child. He was adept, too, and

rarely got caught in the act.

GRANDMA'S SEWING

Grandmother had six granddaughters and she trained each of us to

sew nicely, though I doubt if any of them ever quite reached the standard

of excellence she expected. One of her prized possessions, given

her as a wedding gift, was a beautiful silver thimble handsomely engraved

with her name on it. As an inducement to our learning to sew, she

promised to give each of us a silver thimble as soon as we could earn it.

To earn it, we would have to be able to make a neat flat fell seam, a French

fell, work a pretty button-hole, and make a nice hem. Nothing but

tiny even stitches would do. I earned my thimble by making a dress

for my favorite doll and the thimble was my birthday present when I was

seven. I still have it.

Learning to sew for me, was not an unmixed joy. Mama hated

to darn, particularly socks. Papa was extremely sensitive to the

tiniest knot or the slightest roughness in his socks and his toes poked

through so easily.

He was inclined to tantrums if he could feel the darned place at

all. From the time I learned to darn, every Saturday afternoon, I was made

to do all the darning of hose for the four of us. The chore was irksome,

not alone because of Papa's exacting demands, but because while I was paid

one nickel for doing the darning, I was required to place that same nickel

in the Sunday School collection the next morning. Sister got her nickel

for the Sunday School collection the same as I but there was never any

explanation as to how she earned it. She got her thimble when she

was ten, but sewing was a talent she never used, or almost never.

RATTLESNAKE

I killed my first rattlesnake at the age of eight. I had been

sent on an errand for Papa and on the way back I saw a small ground rattler

crawling along by the side of the road. It was very light in color

and almost the same shade of light gray-tan as the ground. I remember

that it had only one rattle and a button. I killed it by jumping

on it and bringing my heels down as hard as I could, then jumping away.

I jumped back and forth, again and again. Still not satisfied that

it was really dead because it continued to writhe, I got a heavy rock and

pounded it. I had no idea that Papa might be watching me from a window

but when I reached home, he met me at the door, angry and scolding because

he was, as usual, impatient with any slight delay that I might cause him.

He threatened to whip me for playing on the way when he had sent me on

an errand for him. From me, he always expected instant obedience.

I told him I had not been playing. He reminded me that he

had watched me. Then I told him about killing the snake. He did not

believe me and accused me of lying. When he went into the yard to

get a switch, fortunately one of the neighbors who lived down the road

came by and remarked to Papa how brave he thought I was to kill that rattler

all by myself. Papa still doubted the story enough that he went to

see the evidence, or else he just wanted to see the snake for he was very

interested in all kinds of reptiles. When he came back, all he said

was that I was never to try to kill another snake in that manner, as it

was too dangerous.

TAKING CARE OF "SISTER"

I cannot recall that Papa ever admitted that he could make a mistake,

not where I was concerned anyway. He was never wrong. Once

when I was about nine, he sent me to bed without any supper and I have

always remembered the incident with a tinge of bitterness. Mama was

to be away from home for the afternoon and Papa was busy with some project

at home that he expected would take several hours to complete. Sister

and I were told to play in the yard and not to bother Papa while Mama was

away.

Soon after Mama left, Papa remembered something he intended to do

at the school building. He would not be far away, and he left us,

telling us not to go outside the yard. He was hardly out of sight

when a little girl we played with frequently came by and asked Sister and

me to go with her across town to see her grandmother. I told her

that Sister and I were not allowed to go so far without permission, and

Papa was too busy for us to bother him to ask to go. Sister went

anyway, in spite of my protests. I stayed home obediently.

Papa came home first. Whatever he had been working on at the

school building had not turned out as he expected and he was vexed about

it. He asked me where Sister was and I told him she had gone with

Luella to her grandmother's house. I never understood why he took

his bad temper out on me, but he said he detested a tattler though I had

merely answered his question. He said it was contemptible for me

to tattle on my Sister and I was ordered to bed with no supper.

Mama came home before Sister did, and it was nearly dark before

the child returned. Sister was not punished in any way. I told

Mama what Papa had said to me and why he said he made me go to bed, but

she never interceded or tried to make it up to me in any way. There

were many other times when Papa showed his preference for Sister in various

ways but Mama never interfered. She must have known that he petted

and spoiled Sister outrageously. Most of the time, Mama herself tried

to treat us fairly, I think.

I know that, as a child, I was extremely sensitive and many times

drew back into my shell, especially if Papa was in the vicinity.

I hardly believe, however, that the attitude of my parents inflicted any

serious or lasting damage to my personality. To some extent, it might

have since I am still inclined to be retiring. It certainly taught

me to depend on my own resources, and never to expect much in the way of

favors from any one.

PAPA'S HEALTH

In my childhood, the one person who never let me down was Grandpa.

I adored him for he understood me and was unfailingly considerate of my

feelings. I knew that he truly loved me, and that I could always

draw on his wisdom and gentleness. I needed that healing balm many

times. Papa was never a robust man, and after teaching ten or more years,

he developed a hacking cough. He became convinced that breathing

the chalk dust of the schoolroom constantly was having an effect very detrimental

to his health. He was haunted, also, by the fear that he would

die early as his mother had done. He was only a stripling when he

lost her and although the doctors did not diagnose her last illness as such,

Papa was convinced that her death was from tuberculosis and when he began

coughing, he feared the same end.

He gave up teaching, for good and all, he said. His preparation

and training had all been in that field and he liked the work. Consequently,

it was a hard decision for him to make, partly because he had no idea how

else he could make a living for his family. After much discussion,

he took Mama home to her parents while he went out to the Texas Panhandle,

hoping that a change in climate would improve his health. He was

sure a change of climate was what he needed. He stayed two years

in Amarillo, only coming home on short visits and his health did improve.

During that time, he sold insurance, but was barely able to make enough

to support himself with nothing left over for his family.

Henry

Lyles married LeNora "Nora" Key, daughter of Mary Emiline Dillingham

Key, who was widowed when Nora was 11 years old. Later Mary

Emiline married Mr. William Jefferson Walsh. They built the

boarding house at 315 S. Crockett in Sherman, which remained in the

family until 1879.

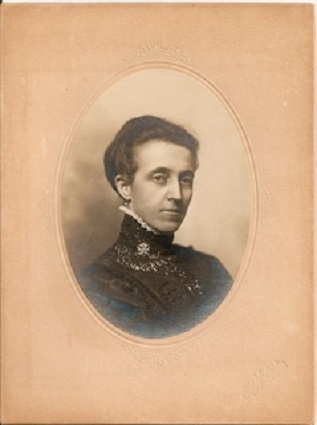

Mary Emiline Dillingham Key Walsh

mother of Nora Key Weems |

Nora Key Weems with her aunt,

America Dillingham Mitchell |

Martha "Mattie" Jane Walsh Fleming

d/o Mary Emiline Key Walsh

half-sister of Nora Key |

Nora Key

high school graduation |

Nora Key

college graduation |

Letter written by "Uncle Buddy", Harvey Lyles Weems, to his cousin,

on a statement form from :

Harvey Weems

LeNora Key Weems

|

"The Roberts, Sanford & Taylor Company, Sherman, Texas.

6/25/99

Miss Katie May Red

Memphis

Dear Cousin

Your Photo & Note came to hand several days since & I intended

writing you some

time ago & tell you how much I appreciated your sending us your

Photo-But have been very Busy. We were invoicing last month & that is

always such a great Big

job and we hardly got through Before we Began dreading the next

time.

Well I do not think you look very natural. Wish you could

pay us a visit would like so much to see you. Say did you know that Jessie Good (Gorch?)

was staying with Ma. This summer Momma and Pa are living here in Sherman. Nora

and I have been Keeping house for about Six Months. By the way Nora is spending

the Summer in Mss. Will be Back about the First of August. I am having

a good time by my Lonesome. I stay some with Momma & some with Mrs. Walsh. I have

not seen Sis for some time the Children have whooping Cough but are getting along all

right. Did you know

we had a Great Big Girl at our house, About five months old.

Ma said tell you She had written you several letters but had rcd.

no reply. Sis is coming

up the last of this week so you see we will all be at home again.

It is quick but out here now Sherman is on sure enough. Are you still Boarding at the

same place that you were

when we were in Memphis two years ago. It doesn't seem like

two years since we were

up there, does it?

Ma still has lots of flowers. Nora has a good many but I don't

know whether she will have any at all when the corms freeze or not. Are you going

home this Summer or not necessarily now that your married where you write. Is Lizzie

visiting you yet. You did

not say in your letter.

Business is rather dull now so I am not so Busy. But will

pay up for it in the fall. We have a few cases of small pox here in Sherman, But don't think there

is any danger.

Well I must Close as I have some Shopping to do. Love to You

and Lizzie. Hope you are having a nice time. Write when Convenient.

Your Cousin,

H.L. Weems

|

When a new town was laid out on the railroad not far from where

Papa and Mama were teaching, Mama's oldest brother saw an opportunity to

establish a new business and he opened up a hardware, furniture and implement

store. It grew so rapidly that he soon brought Grandpa into the store to

help. In a little while there was more work than the two of

them could handle and they hired a man.

Harvey Weems ran a hardware store until his death in 1906.

This is the picture

of the stock room - Harvey is front, left.

They

wanted Mama to help them with the bookkeeping and some clerking.

She agreed to do so, but when school time drew near, she was to take

over

the primary department in the new brick building that was hardly

completed.

So while Papa was recuperating in west Texas, Mama, Sister and I lived

with Mama's parents. We knew everybody and everything looked

rosy.

Then suddenly, Uncle Buddy was stricken with acute appendicitis. By the

time the doctor decided that was the correct diagnosis, it was too late

to take him to the one northbound train that would carry him to the

hospital.

Thirty miles from the nearest hospital, his appendix burst and though

he

was taken to the hospital and the operation performed, it was too late

and he died in four days. It was a great bereavement for the

whole

family, and he left a young widow with two small girls, the oldest,

Mary Weems Elam, aged 5, & the youngest, Annie Lou Weems, aged

3, named after Harvey's sister, Annie Lou Weems Lanham.

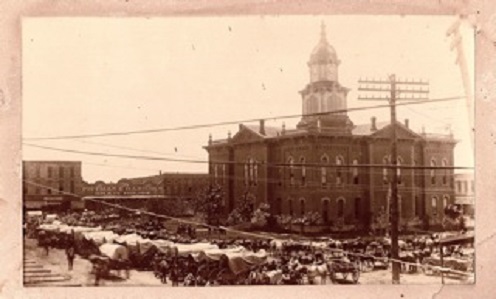

Lenora "Nora" Key Weems

widow of Harvey Weems

She ran the library for about 30 years after her husband's death.

Courthouse & Library

Sherman, Texas

pre-1900

Uncle Buddy had been the manager of the store, and Grandpa

was getting too old to continue carrying the whole responsibility for long.

Mama redoubled her efforts to help, and between the two of them they managed

to carry on until the business could be disposed of without great loss.

"Uncle

Buddy" & Nora Weems daughter Mary married Mr. Elam. Her

daughter was Mary Lou Weems and her granddaughter was Carolyn A.

Rogers, contributor of the information & photographs.

James Madison Weems Sr. home at Celina

James Madison Weems Sr. with wife Kittie, Catherine Red Weems, and

his daughter Annie Lou Lanham Weems with her two daughters Carrie Lee

Lanham (Autry) and Kittie Lanham (Oakes)

The

small town where Mama's parents lived was a very pleasant one. Grandpa

had built a comfortable home set on a plot large enough for him to have

a wonderful vegetable garden and for Grandmama to have all the space for

flowers she could possibly want. To her, roses were never just roses,

they had to have names, and she made it a point to call them only by those

designations. Along the wire fence, she always had a long space reserved

for her sweet peas, the finest I've ever seen growing. The gravel

walk was outlined with carnations, and there was mignonette, sweet basil,

and all the best of the old-fashioned posies with many of the newer ones.

GRANDMA WEEMS

She planted cypress vines near the porch columns and twined great

ropes of this ferny-leafed plant around those pillars. Their brilliant

red and green attracted humming birds every summer and sometimes, I have

seen as many as eight at once, sipping nectar from the dainty trumpets.

Once, when I was standing still to watch them, I put out my hand

and caught the brightly jeweled little creature. That was a thrill

I shall never forget. I was careful not to injure him and I took

him into the house to show him to the other members of the family.

He had tiny claws like fine black wire and I could feel his frightened

little heart's racing beats against my palm. After each of us had

examined him, I took him back to the vine and released him. He darted

away, but I was sure he came back again in a very short time.

A few weeks later I was equally as fortunate when I found a

hummingbird's nest. They are usually so well camouflaged that a

person can

look directly at them without knowing a nest is there. Such a

rare

discovery few ever make, as it looks more like a mossy knot on a vine

or branch. The one I found was like that and it held two tiny

eggs

about the size of garden peas.

During the time we lived with our grandparents, Sister and I enjoyed

many new experiences. Once Uncle Mat wrote to Mama to send us up

to see him on the day the circus was to be in town. Mama decided

that was an important occasion, important enough that she even let us miss

a day of school and ordinarily we had to be running a temperature to get

out of that.

For the first time, we rode on the train without a grown-up and

that made us feel almost adult. Uncle Mat met us at the train and

took us to the circus himself, with his own two smaller children and three

or four others. Did we have fun? It would be hard to tell who

had the most!

When we returned home, we tried to remember and act out everything

we had seen. Grandpa's old horse, Bill, was not cooperative.

I could and did stand up on his back, but he would not trot around the

barnyard, which was just as well because I had not remembered to put any

kind of surcingle on him. All he did was stand and switch at flies.

Sister and I were more successful with our trapeze act. We

found a long two-by-four and stretched it across the narrow space between

Grandpa's barn and the one belonging to our next door neighbor. With

the big barn door open, the space about four feet wide was ample for our

stunts and the door gave us a screen for a measure of privacy. Our

two-by-four was high enough that we could dangle a double trapeze below

it for our practice performances.

Sister was light enough that I could easily swing by my knees with

a leather strap between my teeth, holding a bar on which she cut her capers.

I could also hang and swing by my teeth while she did stunts on the bar

above me. We both hung by our heels, balanced on one foot, turned

flips, and swung up and down like monkeys. It was great fun.

We were shielded by the two barns for complete privacy, or so we thought. Our

neighbor was an old maid with a lot of curiosity. She slipped into

her barn and peeked through the cracks to find out what we were up to.

She was horrified and reported to Mama that we would break our necks on

that rigging. The circus will never know that they missed star performers

because of that meddlesome old busybody.

MUSIC LESSONS

About this time, Mama decided I should have the advantage of musical

training. A new music teacher had come into town and the school board

provided a room in the school building where she could give private lessons

to those children whose parents were willing to pay the modest fee.

Helen Brightman was truly gifted. She could play any instrument with

the minimum of effort but she was especially good with the violin and piano.

Her classes were quickly filled. I wanted to try violin and begged

for that training but Mama wanted me to have piano training.

I have never considered that I had any special talent in music,

though I enjoyed working even at scales when I was taking lessons from

Miss Brightman. Since we did not have a piano at home, I went to

school early to practice before school started and put in half an hour

everyday before reporting to my classroom for regular schoolwork.

After school, I practiced again for an hour and sometimes went back on

Saturday. With that much practice, naturally, I made rapid progress

and soon caught up with some of the other pupils who had started long before

I did. Miss Brightman was an excellent teacher but she discovered

a slight deafness in my left ear and frankly told my mother that the imbalance

in my hearing would prevent me from ever becoming a real musician.

No one had ever noticed this defect before. At any rate, the slight

amount of music I was exposed to permitted me to play simple hymns, and

some marches for school programs.

6TH GRADE

The teacher I had for my sixth grade studies was a funny, quaint

little woman whose age we often wondered about. She was an "old Maid"

sister of the local doctor, and he was far from young. I think at

that time Miss Martin must have been several years beyond present retirement

limits but she was still one of the best teachers I had during grade school.

She was the one who discovered in me a talent no one else had ever

taken the trouble to notice and it came about in a way that I was slightly

ashamed of. I do not recall what she did that I did not like but

she made me angry about something, probably it was a correction for whispering,

a fault I was often guilty of while in her room. Anyway, I drew a

cartoon of her. It was slightly exaggerated, particularly in the

number of wrinkles, but at the same time it definitely was a likeness.

Any one who knew her would recognize that. I became so absorbed in the production

that I did not have time to cover it when she came up behind me.

I expected at least a scolding, and possibly I would have to stay after

school. It certainly did not flatter her, but she liked it.

Said it was a portrait she would always treasure, and she showed it to

Mama and others with the comment that such talent should be developed.

I sincerely wish it had. Mama, who graduated in painting under

one of the best teachers of the time and who had considerable talent herself, never gave me the lessons I wished

for. Part of the time while I was growing up, she taught painting, but

the only thing I can remember drawing during the lessons she was giving

others was a single charcoal drawing of a jug. She never had

the time to give me lessons, always promising to do so in the future.

"BOY CRAZY"

It seems to be the nature of girls to go through the stage of being

"boy crazy" and I was no exception. It hit me when I was about eleven,

and during the time that I was in Miss Martin's room. I was not the

only one so affected as my chum and I really suffered with a terrific case

of it. I could hardly study and was constantly watching to see what

that certain boy was doing. We had what was called a "desperate case" and

it was much longer lasting than such affairs usually seem to be.

Dee and I were about the same age and as I look back in memory, it seems

that I thought he was just about perfection, everything that any girl could

want. He had beautiful eyes, a fresh complexion that most of the

girls envied, and a charming smile. But we were too shy to ever talk

to each other, more than just a word or two. However, it was perfectly

understood between us that I was his girl and he was my sweetheart.

When Christmas came, and as usual the whole family went to the Christmas

Tree Celebration at the Church, Dee surprised me by putting a nice comb

and brush set on the tree for me. Once during the following January,

a snow and sleet storm left enough ice on the school ground that we could

slide. The hill was slippery enough that under close supervision or chaperonage

of the teachers, the girls and boys were permitted to play together

since such conditions occurred so rarely that far south. All during

recess, Dee and I actually clasped hands and slid together down that slope.

That was the height of daring for both of us as we were so painfully shy.

Not long after that, we wised up to the fact that the older boys

and girls were passing notes to each other during school, a practice that

was strictly against the rules but Dee figured that if they could get away

with it, we could too. Shortly after we caught on to what the others

were doing, I found a love note from Dee in my speller. I was thrilled

and took most of the following study period to compose a suitable answer.

Each time we passed notes, they got mushier and sillier until a glimmer

of sense finally penetrated my befuddled little brain, and I wrote Dee

I simply would not keep writing such sticky-sweet stuff any longer.

I told him I liked him just as much as ever, and that I expected to keep

on liking him a lot, but we would both be embarrassed if any one else happened

to read the stuff we had been writing. We did not stop writing notes

altogether but we frequently exchanged problems in algebra with "You are

my sweetheart" or something similar attached. A few days later, Dee had

to stop in one of the stores on his way home after school to pick up a package for his mother. We always

had some homework and he had his books with him, but one of his books slipped

unnoticed on to the counter and he left it in the store. A little

later, one of the teachers came into the store and the merchant gave him

Dee's book to be returned to Dee next morning. The teacher found

in it a note I had written Dee. It simply said "I like you, Dee." The

first thing next morning, Dee was called into the principal's office and

questioned about that note. In the beginning, Dee refused to say

who had written it, or how or when he had received it. He said nothing

at all but he was terribly upset and somewhat scared. He worried

about the kind of punishment he would let me in for if he told. The

principal reminded Dee that the handwriting could easily be identified by comparison,

and he insisted that he was already reasonably sure just which girl wrote

it. Dee was beginning to get over the surprise of finding that my note

was in the hands of the principal. He mentioned that since the note

was not found on the school grounds, and that there was nothing to show

where or when it had been written or passed, the matter should be outside

school supervision. Besides, who could possibly see anything wrong

in an innocent scrap of a note like that.

By using my note as a lever, the principal expected to pry information

out of Dee and make him divulge the names of other pupils suspected of

writing notes as well. Dee positively refused to give any names though

he admitted that he had seen several notes in the hands of other boys,

some of which might or might not have been passed at school. After

lengthy discussion on the subject, Dee extracted from the principal a promise

of immunity from punishment for any of us and that my name would not be

mentioned. In return, Dee said we would write no more notes of any

kind.

At recess, Dee met me in the hall to tell me about what had happened

and though we did not know it then, the principal was discussing the matter

at the same time with our grade teacher. The result of that discussion

was that the principal called a meeting of the upper grades in the auditorium

immediately after lunch. He delivered himself of quite a homily on

the subject of notes. He warned the assembly that in the future,

severe punishment would befall any pupil caught writing or passing notes.

When he quoted my little note word for word, Dee and I felt that he had

failed to keep the terms of his agreement and that we were both embarrassed

by the amount of teasing we had to endure following the public reading

of our little missive. Our childish romance lasted more than a year

after that episode, though we finally quarreled and broke up. So

ended an idyllic phase of my childhood.

CELINA, COLLIN CO., TEXAS

[Celina - First romance with Dee Finley, then George Jackson.

The new school building and my climbing stunt. Skating on the school

ground, Carrie Mann, the ugly one]

This new Texas town grew from nothing before the railroad came linking

Oklahoma to Dallas and Ft. Worth, and extending the market for cattle into

Kansas City and St. Louis. Almost with the first train, shops and

businesses were there, a flour mill, bank, drugstore, other merchants,

all came in as quickly as buildings were erected to house them. The

town was incorporated and a city council elected, a mayor and town marshal

chosen, ordinances passed and it seemed that all the processes were proceeding

in regular order. Very soon, it seemed that all the necessary

businesses were there.

One of the first resolutions the town council passed with full agreement

was that should be no Negroes permitted to live within the incorporated

city limits and with one exception, this statute stood for many years. This one exception came about in a rather unusual way. After

the council had taken stock of the various facilities, they found that

no provision had been made for a hotel and a hotel was badly needed.

Several meetings of the council produced no results. The longer it

was put off, the greater the need became. Finally, some one thought

of Mrs. Nugent, a widow with a family to support, and little means with

which to do so. It was suggested that with the backing of several

men who had been friends of her late husband and who could advance her some small amount of capital and

help her find a suitable building for a small boarding house, that would

have to do until better could be provided. Mrs. Nugent was approached

with the proposition and was pleased with the thought. She was an

excellent cook, and could be expected to set a good table. She made

just one stipulation;

she would not undertake the business unless she would be permitted

to have with her to help her, a certain old Negro man who had been with

her family for many years. Old Mark was his name and she would provide

a small cottage in the rear of her boarding house, where he could stay.

She would guarantee that he would cause no trouble and she would not come

without him.

The city council debated the matter during several meetings, but

in the end they bowed to her determination. Old Mark came.

He was an odd looking man, short, with heavy shoulders and very long, muscular

arms. His face was deeply wrinkled, and he was bald except for a

grizzly gray roll behind his ears. Soon he was a familiar figure

around the town, and quite an asset, in his way. If any of the white

ladies had extra heavy work, she always tried to get Old Mark to help her.

He was the quickest and best hand to clean they could possibly find and his washings were always

snowy white. Sometimes, when work at the boarding house was slack,

Old Mark would do as many as four big family washes in a day, and all the

while, he would sing some old religious hymn in a low mellow humming as

he worked.

The city resolution stayed on the books, however, and no other colored

people were allowed to stay. Once one man tried to bring a couple

in but found he could not. That happened this way. The druggist

had a sick wife and white help was impossible to get, or nearly so.

The few white girls who would work out, generally got married after only

a few months. After several such experiences Mr. Lake decided it

was hopeless to keep one such a short time, he wanting something more permanent.

He put a small house on the back of his lot only a few steps from

his home. Then he carefully selected a colored couple, the man was to work

on Mr. Lake's farm a short distance out of town and the woman was to do

the housework for Mrs. Lake. He thought he had the ideal arrangement.

But it did not work out that way. The couple came in rather late in the

afternoon, and apparently no one observed them there. They went about

their duties quietly the next day but that night, shortly after dark, a

large bundle of switches were found tied to their front door. They

were frightened and appealed to Mr. Lake. He promised them that everything

would be all right, that he would take the matter up with the city authorities

and he was sure they would agree.

Besides, they were on his property and he would protect them.

The threat implied by the bundle of switches was probably only the work

of some irresponsible boys.

Early the next morning, Mr. Lake called on the mayor and told his

story. The mayor reminded him that he was present when the resolution

was passed and should have remembered it; however, his Honor agreed to

call a meeting of the council for discussion if Mr. Lake insisted.

Mr. Lake did insist. The council met and with little or no real discussion

refused to rescind the ordinance.

But Mr. Lake still believed that he was within his rights, and again

told the colored couple they could stay anyway, as he would keep his promise

to protect them. However, that was the night another bundle of switches

appeared in the same mysterious manner, only this they were tied to Mr.

Lake's own front doorknob. A note of warning was attached, and when

Mr. Lake read that, he decided discretion was the better part of valor,

and moved the pair out of town to his farm early next morning. And

as long as we lived in that town, the ordinance was still in effect.

THE BUTCHER SHOP

One

situation that existed in the past but does not still continue was the manner in which meat was provided for the town tables. Mr.

Callahan, a huge, rugged man, operated the local butcher shop. He

owned or leased a big pasture out beside the country road that passed Grandpa's

home. It was probably a mile outside the city limits but there were only

two or three houses between our place and the open shed where he butchered

the animals.

We could see from our yard when he or his helper was there but it

was too far for us to see the operation in detail. We always knew

though when he was dressing meat for a flock of buzzards moved in and circled

round and round, waiting for the offal.

Mr. Callahan rarely bought more than two or three steers at a time

but he usually kept a few fattening feed pens to provide a constant supply

of meat for his shop.

One Monday morning during the summer when Mama was at home, Old

Mark failed to show up to do our washing. Grandmother and Mama decided

that for once they would do it themselves. They started early and

before ten o'clock white sheets and petticoats were billowing on the lines

in our back yard. About that time, Mr. Callahan bought a big wild range

steer. His man and the farmer who sold it started to take the animal

out to the slaughter yard but the beast had other ideas. He was strong

enough to snap the lead rope they tried to use, and neither of them were

expert enough with a lasso to get another rope on him. The brute

was so enraged, they yelled for another rider to help them and the three

men started driving him away from the center of town. They managed

to haze him our way.

Mama saw the critter half a block away and shrieked a warning.

She and Grandmother scrambled wildly into the back door just in time, but

I was around at the side of the house and ran for the front door.

I had no idea from which direction the danger was coming. When I

reached the front steps, the brute had sailed over our four-foot fence

and was charging right at me with his head down and brandishing foot-long

horns. I'll never know how I did it, but I clambered onto the porch

as he slid by me tossing those vicious horns. It was a near thing

but I was lucky.

The steer charged on through the yard, slashing at some of the sheets

on the lines. Then he saw Old Bill, Grandpa's smart old horse in

his yard. He charged at him, but the high fence there held. Old Bill

bolted out of sight into his stall. The beast might have cleared

even that high fence but the yard was too narrow for him to have a run

at it, and he stood there snorting and pawing the ground until one of the

riders managed to open our big side gate without dismounting. The

three men were afraid to enter the yard and drive the steer out but when

his attention was attracted and he saw the riders circling around the yard,

he charged out the gate and at

them. Their horses avoided the rush and after much strenuous

effort, they finally managed to corral that steer in one of Mr. Callahan's

feed lots.

Mama and Grandmother were still in a great state of excitement when

Grandpa came home to dinner at noon. After listening to their account

of the incident and my narrow escape, Grandpa jammed his hat down on his

head and strode out of the house without waiting to eat. He was gone

about half an hour, then returned. He made the quiet comment, "It won't

happen again!"

That was all he ever said about the incident at home, but the whole

town buzzed for a week about what he said to Mr. Callahan. Grandpa

was a very quiet, gentle man, who never raised his voice and he had lived

in the community a number of years without any one ever seeing him in anger.

Mr. Callahan was big and bluff. His fiery temper was easily roused

and it was no uncommon thing to hear him bellowing like a mad bull.

A number of times, he had spent the night in the calaboose for fighting.

But then Grandpa stalked into the butcher shop and pungently expressed his

indignation. Mr. Callahan's jaw dropped and he stood rigid with amazement until

Grandpa finished his tirade and started to leave.

Mr. Callahan stopped him. "Mr. Weems, I ain't never took such

a dressing down from nobody before. You are supposed to be a Christian

and you are a prominent member of the church. Ain't you ashamed to

git mad and bawl a man out like you jest done?"

Grandpa snapped back, "If you read your Bible any, you'll find mention

of such a thing as righteous wrath! You have just seen a sample!"

And he turned and walked out.

TRAVELING EVANGELIST

[Sister and Sid and the ants. Old Bill. My first faint

- Mama thought I had been marked from birth.]

Shortly after this occurrence, a traveling evangelist set up his

tent on a vacant lot near the downtown section. He was a good preacher

and was soon drawing interested crowds every night. His revival had

been going on about ten days and its success was noted when he announced

that about forty people had been converted and would join the churches

of their choice. The town handy man, Lige Collins, had been cajoled into

going to the services a few nights. Some of the men who knew him

were urging him to go down to the front bench for prayers. He loved

his bottle so well that he felt religion was not for him. Well-meaning

friends suggested to the evangelist that if the opportunity presented,

he should talk to Lige. A confirmed sinner like Lige would...a brand

snatched from the burning. As it happened next morning, the grocer wanted

his show windows washed and hired Lige for the job. With a pail of

dirty, soapy water and a long-handled brush, he was working on this chore

when the preacher chanced to stroll by. The minister was a dapper little man with a fresh white

shirt and neat gray suit. Stopping to speak to Lige, he invited him

to attend services that night.

Lige merely grunted and continued to slosh water around with his

mop. The preacher inquired what faith Lige embraced and exhorted

him to have a thought for his salvation. Lige was in no humor to

listen. Suddenly, he swung his wet mop around and smacked the evangelist

in the chest with it. "Just why did you do that!" the preacher asked in

a mild voice. Lige said nothing and dipping his mop back into the pail,

turned back to the window. When the preacher repeated his question,

Lige swung his mop again, this time striking him in the back. To his astonishment,

the preacher stepped forward, clipped Lige neatly on the chin and sent

him sprawling. Lige scrambled to his feet and moved in for a fight.

He met a fast upper cut with a one, two that sent him down into the ditch.

As Lige lay there, one eye rapidly closing, he asked how come.

Men of God were not supposed to get into fistfights.

The preacher quoted the Bible command, "If a man smite thou, turn

the other cheek. I did that! Then I used my own discretion."

DEPUTY GROVER COX

[Along with the businesses that moved in to make the new town came

the churches. At first, the various congregations met wherever they

could find a suitable place, but soon buildings were put up for Methodists,

Baptists, Presbyterians, and Christians. About the last to come in

were the Catholics. This was a Protestant community and only a few

families belonged to the Catholic Church.

The plot the Catholics chose for their church was directly across

the street from Grandpa's house. Father Vernamont.

While the town was new, and stores were being hastily erected, no

provision was made for offices, not even a much-needed notary. The

notary was there in the person of Grover Cox. Because of his friendship

with the Cox family, my uncle arranged for Grover to put his desk in the

front of the store occupied by the hardware department. Mr. Cox was

the smallest dwarf outside of a circus, it seemed, and he had been offered

a salary with Ringling, so rumor had it. He was slightly under three

feet in height and had tiny hands and feet, but his limbs were quite short

and his head and body large in proportion. He was considered quite

a brilliant man, with considerable legal knowledge, largely self-taught,

I imagine. He was well liked and was usually kept quite busy with

his notary work, deeds, mortgages, contracts, and such. He came from

a good family and had several brothers, all of whom were normal in size.

One of his brothers, Walter, was town marshal but real frontier

days were past and barring an occasional drunk, and a rare outbreak of

fisticuffs, there was little duty for the marshal. Even Saturday

nights were usually quiet, though if there should be any disturbance Saturday

afternoon or night was when it would happen.

One Saturday, Walter had business in the county seat and was away

until late. That happened to be the time when three newcomers from

a neighboring community went on a rampage. They were drunk, rowdy

and quarrelsome and they threatened to shoot the town up. They did

fire a few shots into the air. When this happened, some one told

them that if the marshal had not been out of town, they would have been

thrown into the calaboose with such behavior. They blustered and

stormed around and boasted that nobody could take them in, and Walter Cox

wouldn't even be a good dogcatcher. To prove this statement, they

swore they would be back the following Saturday to show Walter and any

of his brothers up, if he dared to try to stop their fun.

Naturally their boasting was reported to Walter, and Grover heard

about it as well. Because he was so tiny and was sometimes out alone

late at night, Walter wanted Grover to have the right to carry his gun and

had sworn Grover in as deputy shortly after taking the office. But

that fact was soon forgotten and only a few knew that Grover was a crack

shot with a pistol.

On the following Saturday night, Walter strolled around the city

square to make his presence known, then waited in the caf where

the disturbance had taken place. At that big desk in front of the

hardware store, Grover appeared to be extremely busy with some of his papers.

But his big Colt was nearly dragging the ground when he stepped out into

the street to intercept the three brothers who had made their brags.

The three burly brothers tied their horses to the hitch rack and

turned to see Grover facing them. "I believe you sent my brother Walter

word that this was to be a family affair," he said mildly. He took

a stance with both tiny hands on his hips and stared up in defiance.

"Just count me in, too, on anything of that sort!"

It was perfectly plain to everyone who saw the meeting that Grover

meant exactly what he said but it was so ludicrous to see the tiny dwarf

facing up to the three overgrown louts that the meeting broke up with boisterous

laughter, all around.

[Mr. MacAdam's romance. Gossip about Mama because Papa was

away so much.]

[My first movie shown at the schoolhouse and not considered very

appropriate for school children as it was all about the Harry K. Thaw Case.

The first ride in an auto, chain drive, and it would not "Whoa!"]

[Papa buys a farm in Oklahoma and comes home bringing

Phme my first

and only present from him, "Eskimo Stories" and then I cannot remember.

Moving to the Oklahoma farm. Sister was given a pup that she named

Punch and Punch was carried on the train with us. Our first long

trip to Vernon, and we forded Red River.]

Sister's name was Carrie Lee Lanham.

"Carrie" Harrison's family was from Brunswick County, Virginia, but she

was born in Edgefield, South Carolina. Her father was Wiley Harrison and her mother

Caroline Elizabeth Talbert, who died in the 1850s. Her father remarried

and the family moved to Noxubee County, Mississippi before 1860 (that is where she

and Robert G. Lanham were married).

He had two daughters and a son with his second wife. It is gone

now.

This was when Walter Lanham moved from Maryland to Edgefield.

The family arrived in Maryland before 1700.

It no longer seems to be around.

Sherman Daily Democrat

August 15, 1916

J.M. Weems Dead

Pioneer Citizen Passes Away at the

Home of His Son Here

J.M. Weems, Sr., seventy-five years of age, a pioneer

citizen of Grayson county and one of the best known and most highly regarded men

in the county, died last night at 12:20 o'clock, after an illness of three

weeks' duration.

Death came at the home of his son Dr. J.M. Weems, No. 826

West Houston street, where he was taken shortly after he became ill.

He is

survived by his wife, Mrs. Kittie Weems, and one son and one daughter, Dr. J.M.

Weems of this city and Mrs. T.W. Lanham of Oklahoma.

Mr. Weems was born and

reared in Durant, Miss., coming to Texas in 1874 and locating in Grayson county.

With the exception of several years spent at Celina, Collin county, during which

time he was engaged in the hardware business at that place, he has lived in this

county.

For many years he was identified with the farming interests of the

county and was a leader in agricultural progressiveness. For eight years he

served the county as a commissioner, and was a splendid official.

during the

war between the states he served four years in the southern side.

Mr. Weems

had long belonged to the Southern Methodist church, and was prominent in its

affairs.

funeral services will be held at the home of Dr. Weems this

afternoon at 5:30 o'clock, conducted by Rev. J.F. Pierce of the Travis Street

Methodist church, and burial will be in West Hill cemetery.

Sherman Democrat

Wednesday, 16 August 1916

Services Held at the Home

of Dr. Weems Yesterday Afternoon.

Funeral services for J.M. Weems, Sr., who

died Monday night, were held Tuesday afternoon at 5:30 o'clock, at the home of

his son, Dr. J.M. Weems, No. 826 West Houston street, conducted by the Rev. J.F.

Pierce, pastor of Travis Street Methodist church.

The following were the pall

bearers: J.L. Wilson of Celina, Joe F. Etter, Stanley Roberts, Forrest Moore,

Will Gough and Jim Snyder, active; Billie Walsh, W.H. Lankford, George

Hardwicke, B.R. Long, Ben Shaw, Judge Dayton B. Steed, W.F. Corbin and F.L.

O'Hanlon, honorary.

The funeral was attended by a large number of people, and

many bearutiful flowers were sent.

Josiah McGaw's father was the Revolutionary War soldier. I

haven't found proof of the Swamp Fox story though they were probably in

a few of the same battles. Her father died in 1849, her mother in 1855.

Should be Dr. Red. James Albert died at age two, before the family left

Mississippi. George R. died in Texas in 1880 at age eight and is

buried with his parents in the

West End Cemetery in Sherman. (note- West Hill Cemetery in

Sherman)

The letter is in the possession of descendants of George Red, who

sent me a copy. He was not on Lee's staff, though he apparently was at Appomattox.

This was an unfinished thought.