Edward Brooke, who represented Massachusetts in the U.S. Senate from 1967 to 1979, was the first African American elected to the Senate in the 20th century. Brooke was born at 1938 Third Street and later lived with his family at 1730 First Street. After graduating from Dunbar High School in 1936, he lived at home on First Street and walked to Howard University, where he received a B.S. in sociology.

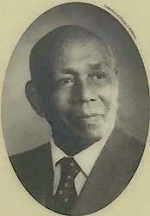

The influential psychiatrist Dr. Ernest Y. Williams, a native of the British West Indies,

lived and worked at 1747 First Street. The Howard University graduate founded the Medical

School's Department of Psychiatry and Neurology in 1940. Years later he recalled attending

at 1967 American Psychiatric Association conference where he "saw a total of 63 Negroes ...

48 of whom came from Howard, and all of whom I had had the pleasure of teaching."

The influential psychiatrist Dr. Ernest Y. Williams, a native of the British West Indies,

lived and worked at 1747 First Street. The Howard University graduate founded the Medical

School's Department of Psychiatry and Neurology in 1940. Years later he recalled attending

at 1967 American Psychiatric Association conference where he "saw a total of 63 Negroes ...

48 of whom came from Howard, and all of whom I had had the pleasure of teaching."

One block to your left is 1635 First Street, once home to comedian Jackie "Moms" Mabley,

known for her raunchy humor and biting social commentary. Mabley was friends with Odessa Madre

of 1719 First Street. Madre, who operated a nightclub off U Street, NW, also ran illegal

prostitution and gambling operations. "She came and went with her Cadillac and furs,"

recalled Judge Annice Wagner, who grew up here in the 1940s. Though some neighbors remembered

her for her generosity, newspapers called Madre the Al Capone of Washington.

One block to your left is 1635 First Street, once home to comedian Jackie "Moms" Mabley,

known for her raunchy humor and biting social commentary. Mabley was friends with Odessa Madre

of 1719 First Street. Madre, who operated a nightclub off U Street, NW, also ran illegal

prostitution and gambling operations. "She came and went with her Cadillac and furs,"

recalled Judge Annice Wagner, who grew up here in the 1940s. Though some neighbors remembered

her for her generosity, newspapers called Madre the Al Capone of Washington.

Just ahead is 127 Randolph Place, formerly Howard University Professor James V. Herring's Barnett Aden Gallery. Herring and gallery partner Alonzo Aden supported the careers of local and nationally known artists including Lois Mailou Jones, Elizabeth Catlett, and Charles White.

Also pictured in the sign above: In 1982 the eight children of Mattie P. and Alfred E. Simons returned for a reunion at 110 S St. NW, the home that nurtured them; Mother and daugther Alberta Randolph and Juletta Smith of 125 Randolph Place laugh with poet Langston Hughes, and librarian Lawrence Hill at a Barnett Aden Gallery event, around 1947; Alberta's mother Bertha Fair Randolph poses at the family fireplace.

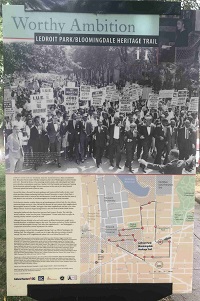

Ledroit Park and its younger sibling Bloomingdale share a rich history here. Boundary Street (today's Florida Avenue) was the City of Washington's northern border until 1871. Beyond lay farms, a few sprawling country estates, and undeveloped land where more suburban communities would rise. Nearby Civil War hospitals and temporary housing for the formerly enslaved brought African Americans to this area in the 1860s. Howard University opened just north of here in 1867.

Around this time, a Howard University professor and trustee and his brother-in-law, a real estate speculator, began purchasing land from Howard University to create LeDroit Park, a suburban retreat close to streetcar lines and downtown. It took its name from the first name of both Barber's son and father-in-law. Bloomingdale was developed shortly thereafter.

For its first two decades, wealthy whites set up housekeeping in LeDroit Park. By 1893 African Americans began moving in. Soon LeDroit Park became the city's premier black neighborhood. Bloomingdale remained a middle- and upper-class white neighborhood until the 1920s, when affluent African Americans began buying houses in the area south of Rhode Island Avenue.

Among the intellectual elites drawn here was poet Paul Laurence Dunbar. The trail's title, Worthy Ambition, comes from his poem, "Emancipation": Toward noble deeds every effort be straining. / Worthy ambition is food for the soul!

Although this area declined in the mid-20th century as affluent homeowners sought newer housing elsewhere, revitalization began in the 1970s. The stories you find on Worthy Ambition: LeDroit Park/Bloomingdale Heritage Trail reflect the neighborhood's - and Washington's - complicated racial history and the aspirations of its citizens.

Mattie P. and Alfred E. Simons, center, front row, gathered their eight children, spouses, and

grandchildren at the family home at 110 S. St., NW in 1952. In 2013 the family marked its 85th year in the house.

This busy stretch of Rhode Island Avenue was a racial dividing line even as DC became majority African American in 1957. "African Americans were not welcome on [the north] side of the street," commented Reverend Bobby Livingston years later, "unless you had a mop and a bucket in your hands." In 1958 Mount Bethel Baptist Church, a 1,500-member black congregation, purchased its church from a white Methodist congregation. Reverend Leamon White oversaw Mount Bethel's move from Second and V Streets. The civil rights activist had worked for desegregation in the early 1950s and in 1963 helped plan the March on Washington. Signs for the march were assembled in Mount Bethel Church.

Memories of discrimination during the 1940s and '50s remain for many neighbors. Across First Street, Rhode Island Pharmacy operated a whites-only soda fountain. Discrimination meant, however, that black-owned businesses thrived, including Johnson's pharmacy and Harrison's Caf on Florida Avenue. Some white businesses welcomed all to sit and eat, including B. Ambrogi's at Third and Rhode Island, later B & J's Barbecue.

Like many DC neighborhoods, Bloomingdale experienced the civil disturbances following the 1968 assassination of the Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. The Safeway near this corner was looted. In addition, "Rioters ... destroyed the inside of" Reservoir Market, recalled Barry Cohen of his family's store just north at First and U Streets. "It was like a bomb had gone off." The building survived only because the upstairs tenant held her baby as she yelled out the window, "Please don't burn us out! I have nowhere to go!"

Rev. Leamon White (second from left) protested the segregation of DC's restraurants

alongside Mary Church Terrell (center) in the 1950's.

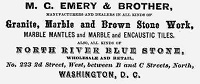

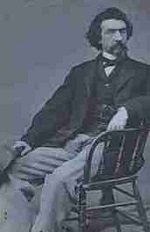

The City Park across the street was once Emery Place, the summer estate of Matthew Gault Emery.

A prominent builder, Emery was Washington City's last elected mayor during the period of home rule. He was succeeded in 1874 by a presidentially appointed board of commissioners, which governed until Mayor Walter Washington was elected a century later. Emery made a fortune in stone-cutting, including cornerstone for the Washington Monument. He excelled in insurance, banking, and new technologies -- electric streetcars and lighting.

During the Civil War (1861-1865), Captain Emery led the local militia. His hilltop became a signal station

where soldiers used flags or torches to communicate with nearby Fort DeRussy or the distant Capitol.

Soldiers of the 35th New York Volunteers created Camp Brightwood here. During the Battle of Fort Stevens in July 1864,

Camp Brightwood was a transfer point for the wounded

During the Civil War (1861-1865), Captain Emery led the local militia. His hilltop became a signal station

where soldiers used flags or torches to communicate with nearby Fort DeRussy or the distant Capitol.

Soldiers of the 35th New York Volunteers created Camp Brightwood here. During the Battle of Fort Stevens in July 1864,

Camp Brightwood was a transfer point for the wounded

The property passed on to Emery's daughter Juliet and her husband, businessman and civic leader William Van Zandt Cox. In 1946 Cox heirs sold the rundown estate to the city for use as a playground. Emery Recreation Center opened in 1959.

Across Georgia Avenue at the corner of Longfellow Street, one block behind you,

was the site of two successive neighborhood department stores. The Abraham family ran shops,

and eventually Ida's Department Store, there from 1915 until 1983. Morton's came next,

part of a chain founded in Washington in 1933. In his early stores, Morton's owner

Mortimer Lebowitz refused to segregate rest rooms or prohibit black customers from trying on clothes

despite local custom.

Across Georgia Avenue at the corner of Longfellow Street, one block behind you,

was the site of two successive neighborhood department stores. The Abraham family ran shops,

and eventually Ida's Department Store, there from 1915 until 1983. Morton's came next,

part of a chain founded in Washington in 1933. In his early stores, Morton's owner

Mortimer Lebowitz refused to segregate rest rooms or prohibit black customers from trying on clothes

despite local custom.

"Imagine a great avenue [with] solid ranks of soldiers, just marching steady all day long, for two days. ..." Walt Whitman.

It took two days for the grand parade of 200,000 victorious Union soldiers described by the great American poet and Civil War nurse Walt Whitman to march down Pennsylvania Avenue past this spot, headed for review by President Andrew Johnson at the White House.

Whitman might have been standing right here on May 23 or 24, 1865. This had been the ceremonial and commercial crossroads of the city since the federal government moved to the banks of the Potomac River in 1800. Pennsylvania Avenue has been an inaugural parade route for every President since Thomas Jefferson. For 130 years, this triangular space before you was the city's town square-home of the Center Market where Cabinet secretaries, government clerks and laborers alike might be seen with a live chicken under the arm.

All around you are reminders of the Civil War. A statue of Major General Winfield Scott Hancock, a hero at Gettysburg, commands a small park across Seventh Street. In the plaza across Indiana Avenue, stands a memorial to the founder of the Grand Army of the Republic, Dr. Benjamin F. Stephenson, dedicated by a few hundred grizzled veterans in 1909. The building where Civil War photographer Matthew Brady had his studio, its exterior only slightly altered, remains around the corner at 627 Pennsylvania Avenue. And the three little buildings at 637-641 Indiana Avenue were witness to it all.

Today, some of the history made here is preserved in the great neo-classical National Archives building

just across Pennsylvania Avenue. Market Space is now the hub of a new downtown, alive with theaters

and restaurants, a new sports arena, museums, shops and homes - a mixture of activities that reflects

its historic role as the heart of the nations's capital.

Today, some of the history made here is preserved in the great neo-classical National Archives building

just across Pennsylvania Avenue. Market Space is now the hub of a new downtown, alive with theaters

and restaurants, a new sports arena, museums, shops and homes - a mixture of activities that reflects

its historic role as the heart of the nations's capital.

Federal style commercial structures have stood at 637-641 Indiana Avenue since the 1820s.

Sergeant Major Christian Fleetwood served with Union fighting forces in the Fourth U.S. Colored Troops

and was awarded the Medal of Honor. Yet African American combat troops were barred by

General William Tecumseh Sherman from marching in the May 1865 review.

Sergeant Major Christian Fleetwood served with Union fighting forces in the Fourth U.S. Colored Troops

and was awarded the Medal of Honor. Yet African American combat troops were barred by

General William Tecumseh Sherman from marching in the May 1865 review.

Civil War photographer Matthew Brady had a studio around the corner.

In November 1997, Richard Lyons peered into the dark clutter in the attic of 437 Seventh Street, inspecting the building in preparation for its planned demolition. His eyes settled on a sign, "Missing Soldiers Office, Clara Barton, 3rd Story, Room 9." He had stumbled upon, and saved, the home and office of the Civil War nurse and Red Cross founder, known as the Angel of the Battlefield. It was a time capsule. Room 9 was still stenciled on the door; 19th-century wallpaper hung from the walls in shreds.

It was from the spot where you now stand that Barton began her work on the Civil War battlefield in 1862, leaving for the front lines at Antietam atop a supply wagon loaded with donated food and medical supplies. She worked as a copyist in the Patent Office at Ninth and F Streets from 1861 to 1865. As a woman, she could not serve in the Union Army, so she devoted herself to feeding , nursing and comforting thousands of Union wounded in the nation's most costly war, a conflict that took more than 600,000 American lives.

After the war, at her own initiative and expense, Barton made her Seventh Street home a headquarters for the search for missing soldiers. She was eventually paid a flat fee of $15,000 by the government for her efforts. Thus she was the first woman to run a federal office. She received more than 63,000 letters of inquiry and wrote 41,855 replies, in the end identifying about 22,000 of 62,000 missing soldiers.

Seventh and D Streets in 1863 when Clara Barton's office was just a few steps up the street off the left side of the picture.

Proud proprietors pose in front of the May Building at 480 7th Street in the late 19th century. Clara Barton's block had been swept up in the city's post-Civil War prosperity.

Clara Barton's Notice

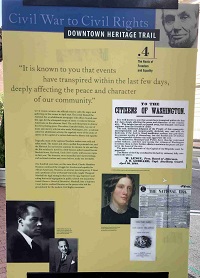

"It is known to you that events have transpired within the last few days, deeply affecting the peace and character of our community."

With these words, city officials tried to calm the angry mobs gathering on this corner in April 1848. The crowds blamed the National Era, an abolitionist newspaper located near this sign, for the attempted escape of 77 African American slaves on the ship Pearl. They threatened to destroy the Era's printing press. The editor, Gamaliel Bailey, was one of many anti-slavery activists who made Washington, D.C. a national center for abolitionist activity. He wrote of the irony of slavery in the capital of a nation dedicated to liberty and equality.

Tragically, most of the captured slaves were sold and taken south. The mayor and others quelled the potential riot, and the National Era survived. In 1851 and 1852, in a new location just a block and a half south of here, the paper serialized a novel by a little known author named Harriet Beecher Stowe. Her book, Uncle Tom's Cabin, sold 300,000 copies in its first year. The dramatic story intensified sectional rivalries and, many believe, made war inevitable.

One hundred years later, on this same block, Charles Hamilton Houston continued the struggle for freedom and equality for African Americans. Houston, a practicing attorney at 615 F Street, and a professor of law at Howard University, taught Thurgood Marshall the legal strategies that led to the 1954 Supreme Court ruling in Brown vs. Board of Education that racial segregation in the schools was unconstitutional. Marshall, later a Supreme Court justice, credited Houston as the person who laid the groundwork for the modern civil rights movement.

TO THE CITIZENS OF WASHINGTON.

It is well known to you that events have transpired within the last few days, deeply affecting the peace and character of nut columnnity. The danger has not yet passed away, but demands increased vigilance from the friends of order.

The cool, deliberate Judgment of the People of this community, unexceptionably and unequivocally declared, can, and will, we doubt not, if the Law is found insufficient, redress any grievance, in a manner worthy of themselves; but the fearful acts of lawless and irresponsible violence can only aggravate the evil.

The Authorities, Municipal and Police, have thus far restrained actual violence; and they now invoke the citizens of Washington to sustain them in their further efforts to maintain the peace end preserve the honor of the city.

The peace and character of the Capital of the Republic must be preserved.

The Mayor of the City (confined to his bed by sickness) fully concurs in the above.

W. LENOX, Free. Board of aldermen

J. H. GODDARD, Capt. auxiliary Guard.

April 20, 1848

Charles Hamilton Houston, mentor to future Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall, had an office on this block.

Harriet Beecher Stowe's Uncle Tom's Cabin was first published near this spot in serialized form in The National Era.

The Civil War (1861-1865) transformed Washington, DC from a muddy backwater to a center of national power. Ever since, the city has been at the heart of the continuing struggle to realize fully the ideals for which the war was fought. This drawing (above) for architect George Hadfield's Greek revival style City Hall/Courthouse (To your right at the end of Indiana Avenue), includes a dome that was never built. Across Sixth Street is the H. Carl Moultrie I Courthouse, a successor to the original courthouse.

The Old City Hall/Courthouse opened in 1822, with offices for the mayor, city administrators, and federal courts. Today it is the city's third-oldest public building, after the White House and the Capitol.

The City Hall/Courthouse witnessed key events in abolition history. In 1848 abolitionist Daniel Drayton faced trial here for larceny and illegally transporting slaves. Months earlier, Drayton had been captured along with 77 African Americans attempting to escape slavery aboard his schooner, Pearl. Drayton was found guilty and served jail time, but was pardoned in 1852. The National Park Service later cited this case when it added the City Hall/Courthouse to its National Underground Railroad Network to Freedom.

On April 16, 1862, during the Civil War, President Lincoln signed the DC Emancipation Act, freeing DC's enslaved people. The law established an experiment called "compensated emancipation," reimbursing slave owners for their human property. Owners came to the City Hall/Courthouse, where three commissioners had the ugly task of putting a monetary value on human life (up to $300 per person). Later President Lincoln did not offer compensation when his Emancipation Proclamation declared the enslaved people of the rebellious states to be free in January 1863.

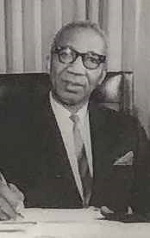

H. Carl Moultrie I (1915-1986)

H. Carl Moultrie I (1915-1986)

The First African-American Chief Judge of the DC Superior Court

Senator Daniel Webster, eloquent advocate for the preservation of the Union and a political giant in pre-Civil War America, lived and worked here. His home and office buildings, now demolished, were similar to the two surviving pre-Civil War buildings alongside this sign. Wester's buildings began where the ally is today, stretching to the west. In the mid-19th century this was a fashionable neighborhood of fine homes and magnificent churches within easy walking distance to the Capitol and near Washington's City Hall/Courthouse.

Webster's unmatched speaking ability helped bring about the Compromise of 1850. The compromise helped delay the Civil War for about ten years and ended the notorious slave trade in District of Columbia. But at the same time strengthened the fugitive slave law that compelled citizens to help capture and return individuals fleeing slavery.

In 1850, at 69 years of age and near the end of his life, Webster made his last great speech on the floor of the Senate in defense of the Union. He filled the galleries with spectators, many of whom were Washingtonians who regularly attended the entertaining and educational congressional debates. Webster likely developed his arguments here in his office.

Among the dignitaries who lived nearby were Senator Thomas Hart Benton of Missouri, John C. Calhoun, vice president under President John Quincy Adams; and Salmon P. Chase, President Lincoln's secretary of the Treasury. Lincoln attended the wedding of Chase's daughter Kate at the family home at Sixth and E Streets, now demolished.

In Webster's day, the First Unitarian Church of Washington stood at the corner of Sixth and D. The Unitarians were among the city's loudest anti-slavery voices. When they tolled the church bell endlessly the day abolitionist John Brown was executed in 1859, the city ordered the bell silenced for good. The former Recorder of Deeds building now occupies the church site.

Secretary of the Treasury, Salmon P. Chase, lived in this fashionable home, now demolished, at Sixth and E Streets.

His daughter, Kate Chase, married Senator William Sprague in a ceremony at the Chase mansion attended by President Lincoln.

503 D Street Formerly law offices and residence of Daniel Webster

Daniel Webster

The building at 604 H Street is intimately connected to the assassination of President Abraham Lincoln at Ford's Theater, just five blocks from here.

During the Civil War this modest brick house was occupied by Mary Surratt [ Mary Elizabeth Jenkins], a Maryland-born widow who took in boarders. Like many in this Southern city that found itself the capital of the Union, she was quietly sympathetic to the Confederacy. She had a son in the Confederate Army. Another son, John Surratt, had become friends with the famous actor, John Wilkes Booth.

Booth, it turned out, had been plotting to capture President Lincoln.On April 14, 1865, the plot changed to murder. Booth, one of a famous theatrical family, was the matinee idol of his day. His dashing appearance caused women to swoon, and both men and women were taken with the handsome young man. He attracted co-conspirators, several of whom, including John Surratt, lived in this house. Booth himself visited several times. Although most likely there was never a formal meeting here, President Andrew Johnson reflected a popular belief in calling it "the nest in which the egg was hatched."

Three days after the assassination, police came to see Mrs. Surratt. By unlucky chance,

Lewis Powell,

already identified as part of the plot, showed up at the same time. The coincidence was

enough for the authorities to implicate Mrs. Surratt. She was arrested, tried and hanged

with three others at Fort McNair in Southwest Washington on July 5, 1865. Booth escaped

to a Virginia tobacco shed, where pursuers found him and shot him to death.

John Surratt

escaped to Canada and went free. More than a century later, Mary Surratt's guilt continues

to be a subject of debate.

Three days after the assassination, police came to see Mrs. Surratt. By unlucky chance,

Lewis Powell,

already identified as part of the plot, showed up at the same time. The coincidence was

enough for the authorities to implicate Mrs. Surratt. She was arrested, tried and hanged

with three others at Fort McNair in Southwest Washington on July 5, 1865. Booth escaped

to a Virginia tobacco shed, where pursuers found him and shot him to death.

John Surratt

escaped to Canada and went free. More than a century later, Mary Surratt's guilt continues

to be a subject of debate.

A number of the Lincoln conspirators pictured here frequented the Surratt house.

Center:

Mrs. Mary E. Surratt

Clockwise from Top-Left:

J. Wilkes Booth

Lewis T. Powell

David Herold,

Michael O'Laughlen

John Surratt

Edmund Spangler

Samuel Arnold

George A. Atzerodt

Mary Surratt Boarding House, now a Chinese restaurant in DC's Chinatown neighborhood.

"This hotel, in fact, may be much more justly called the center of Washington and the Union than either the Capitol, the White House, or the State Department...." Nathaniel Hawthorne, Civil War reporter for the Atlantic Monthly

At 6:30 a.m. in late February 1861, President-elect Abraham Lincoln and his security team headed by Alan Pinkerton slipped into what was then called Willard's Hotel, an earlier version of the hotel now at this site. Assassination threats dictated this quiet arrival. The Lincoln family stayed there for ten days prior to the inauguration on March 4th. Willard's was hosting an unsuccessful peace conference at the time, a last ditch effort by delegates from 21 states to avert war.

Julia Ward Howe,

a hotel guest during the war was awakened one night to the sound of Union troops marching by, singing as they went.

Then and there she penned the words of the Battle Hymn of the Republic, the song that became the Union anthem.

Julia Ward Howe,

a hotel guest during the war was awakened one night to the sound of Union troops marching by, singing as they went.

Then and there she penned the words of the Battle Hymn of the Republic, the song that became the Union anthem.

Later, President Ulysses S. Grant popularized the word "lobbyist" in this hotel. The president frequently enjoyed relaxing with a brandy and a cigar in Willard's lobby. As word spread about his nightly ritual, many men congregated there, waiting to approach him about their causes. Grant called them lobbyists and the label has remained.

There has been a hotel on this site since 1816; young Henry Willard became manager in 1847 and bought it with his brother in 1850. During the Civil War, rooms cost between $2.75 and $4 per night and included lavish meals. In August 1963, Martin Luther King, Jr. finished work on his famous "I Have a Dream" speech in his suite at the Willard.

When it was built in 1901, the current Willard Inter-Continental Hotel was one of Washington's first skyscrapers. The Beaux Arts structure was designed by Henry Hardenbergh whose work includes the Plaza Hotel and the original Waldorf-Astoria in New York.

"Alvin, Washington, D.C., is the place for us." So wrote Samuel Walter Woodward to his business partner, Alvin Lothrop, in 1879. The young entrepreneurs were looking for a new location for their innovative dry goods store near Boston, Massachusetts. Unhappy with the bargaining common in stores of the day, they were the first to charge a fixed price and to allow returns.

Woodward recognized the new vitality and promise of the nation's capital. Since the end of the Civil War just 14 years earlier, Washington had new importance as the center of a strong federal government. It had been thoroughly modernized, with broad paved streets and avenues, sewers, gaslights, and thousands of new trees. Americans were flocking to the newly important capital to take government jobs and start businesses.

Woodward and Lothrop joined them in 1880 and opened their store near Seventh and Pennsylvania Avenue. In 1887, they moved their establishment, now enlarged to a modern "department store," to this location, spearheading the development of F Street as the city's premier downtown shopping boulevard. Affectionately known as "Woodies," the store was a Washington tradition until its closing in 1996.

Crowds throng F Street near Woodies at holiday time in the 1940's

Relief artwork on exterior of building

Store's Interior

America's oldest Navy and Marien installations are just blocks from where you are standing.

This is the northern edge of a Capitol Hill community shaped by the presence of the U.S. military. Eighth Street is its commercial center. The Washington Navy Yard anchors the far end, where Eighth Street meets the Anacostia River. At this end, just one block from here, is the Old Naval Hospital. And halfway in between is the Marine Barracks, home of the United States Marine Band and inspiration for a local boy who made good: John Philip Sousa.

Eighth Street was planned as a commercial avenue leading to a natural harbor on the Anacostia River, where city designer Pierre L'Enfant designated a future trade center. But in 1799 President John Adams decided instead to give the site to the Navy for its Washington shipyard. Either way, Eighth Street was destined to be a street of business. In 1801 President Thomas Jefferson added another military installation: the Marine Barracks at Eighth and I Streets. Soon, as the Navy Yard became a major employer, small businesses emerged along Eighth.

This spot became an early crossroads. Here Eighth Street intersected with a road that lead from the ferry landing on the Anacostia to the site for the Capitol and beyond to Georgetown. That road is today's Pennsylvania Avenue.

This community grew with the young nation. As you walk this trail, you'll see a variety of 19th- and early 20th-century building styles. They are reminders of the neighborhood's economically diverse population - laborers, merchants, marines and sailors, and the politically powerful.

The brand-new Wallach School (1863), designed by noted architect Adolf Cluss, was located where you can see today's Hine Junior High School across Pennsylvania Avenue.

You are standing across from Marion Park, named for Francis Marion, the celebrated South Carolina state senator (1782-1790) who earned the moniker "Swamp Fox" for his brilliant stealth tactics against the British during the Revolutionary War.

Dorothy Owens Hawkins grew up beside the park in 515 E Street, next door to her grandfather William Owens,

a policeman who lived in 513 and was stationed at the Fifth Precinct across the park (no Substation 1-D-1).

He also served at the White House As a child in the 1920s, Dorothy would take a table and chairs to the

park for tea parties under the trees.

(Dorothy Owen's father Charles poses by the backyard

water closet, complete with modern plumbing, which supplemented the indoor facilities.)

Ahead of you on the corner is 423 Sixth Street, known as the James Carbery House. Carbery served as a Navy Yard architect and engineer, and as an elected city Common Councilman (1826-1829). He purchased the 1803 Federal style house in 1833 and lived there until his death in 1852. After Carbery's heirs sold the house in 1881, the tower was added and the roofline was altered. Before Carbery purchased the house, it was owned by Robert Alexander, first architect of Christ Church, who lived there and later rented it to his friend and colleague, architect Benjamin Henry Latrobe.

The church and parsonage across Sixth Street were designed for Mt. Jezreel Baptist Church in 1883 by Calvin T. S. Brent, the first African American architect to practice in Washington. Built by freed slaves, the church (now Pleasant Lane Baptist Missionary Church) is one of seven Brent designed, of which only three remain.

Marion Park, 1927

Note: The Owens family mentioned is this family from the 1920 US census in Washington DC: Charles R. Owens, 25 (stenographer, hardware store), Clara S. 23, Dorothy J. 4 & 5 months

This neighborhood has been "A Place Between Places," where races and classes bumped and mingled as they got a foothold in the city. It has attracted the powerful seeking city conveniences as well as immigrants and migrants just starting out. By 1900 the Shaw neighborhood lay just north of the downtown federal offices and white businesses, and south of the African American-dominated U Street commercial corridor and Howard University.

Longstanding local businesses took root here, and leaders flourished: Carter G. Woodson, Langston Hughes, John Wesley Powell, B. F. Saul, and A. Philip Randolph. The nation's finest "colored" schools were here too. By the 1930s the area was known as Midcity or Shaw (for Shaw Junior High School).

Over time the shops of Seventh and Ninth streets became a bargain-rate alternative to downtown's fancy department stores. There were juke joints, Irish saloons, storefront evangelists, delicatessen....

After this neighborhood's original Northern Liberty Market on Mount Vernon Square was razed in 1872, a new Northern Liberty Market was built along Fifth between K and L streets. When owners decided that fresh farm products weren't drawing enough customers, they added a massive second-floor entertainment space. This was Convention Hall (1893), the city's first convention center, seating 6,000. While farmers did business on the first floor, the second floor hosted balls, banquets even bowling tournaments. Soon it was called Constitution Hall Market.

When the Center Market downtown on Pennsylvania Avenue was razed in 1931 to build the National Archives,

many vendors moved here. Convention Hall Market became New Center Market. Then in 1946 the building burned

in a spectacular fire, visible for miles. Partially rebuilt with a low, flat roof,

it continued to sell foodstuffs despite the arrival of modern supermarkets. But by 1966 the vendors were gone,

and the building became the National Historical Wax Museum. When the museum closed, rock 'n' rollers

flocked to "The Wax" for concerts. The city's second Convention Center opened in 1983 at Ninth and H streets,

NW, and two years later the Wax Museum was demolished.

When the Center Market downtown on Pennsylvania Avenue was razed in 1931 to build the National Archives,

many vendors moved here. Convention Hall Market became New Center Market. Then in 1946 the building burned

in a spectacular fire, visible for miles. Partially rebuilt with a low, flat roof,

it continued to sell foodstuffs despite the arrival of modern supermarkets. But by 1966 the vendors were gone,

and the building became the National Historical Wax Museum. When the museum closed, rock 'n' rollers

flocked to "The Wax" for concerts. The city's second Convention Center opened in 1983 at Ninth and H streets,

NW, and two years later the Wax Museum was demolished.

Notice the handsome rowhouses on your right. These are part of a full square of 53 houses designed and

built in 1890 by the prolific

T. Franklin Schneider.

Developing an entire square, though common in most city neighborhoods, was unusual in Shaw, where most houses were

built individually.

Notice the handsome rowhouses on your right. These are part of a full square of 53 houses designed and

built in 1890 by the prolific

T. Franklin Schneider.

Developing an entire square, though common in most city neighborhoods, was unusual in Shaw, where most houses were

built individually.

A post-Civil War building boom brought grand new houses to this convenient area. By 1881 Blanche Kelso Bruce, the first African American to serve a full term in the U.S. Senate, and Major John Wesley Powell, pioneering director of the U.S. Geological Survey, lived on this block.

Born enslaved in Virginia, Bruce (1841-1898) escaped from slavery, attended Oberlin College,

then became rich buying abandoned plantations in Mississippi. The Mississippi Legislature elected

Bruce to the U.S. Senate. From 1875 to 1881, Senator Bruce worked to aid destitute blacks and

improve government treatment of Native Americans. Later, he served as register of the U.S. Treasury

and recorder of deeds for Washington, D.C.

Born enslaved in Virginia, Bruce (1841-1898) escaped from slavery, attended Oberlin College,

then became rich buying abandoned plantations in Mississippi. The Mississippi Legislature elected

Bruce to the U.S. Senate. From 1875 to 1881, Senator Bruce worked to aid destitute blacks and

improve government treatment of Native Americans. Later, he served as register of the U.S. Treasury

and recorder of deeds for Washington, D.C.

Bruce and his wife, Josephine Willson Bruce (1852-1923), a founder of the National Association of Colored Women (1896), lived in the Second Empire French style house at 909 M Street.

Major John Wesley Powell (1834-1902) and his family moved to 910 M Street (since demolished) in 1881 after he took over the U.S. Geological Survey. Powell, a scientist and war hero, lost his right arm during a Civil War battle. He led the first official survey of the Grand Canyon in 1869, and argued that Native Americans had the right to live according to their own tradition.

Small houses, commercial buildings, and immigrant churches developed here after 1910. By the 1930s

the rich had moved on, and landlords divided mansions into rooming houses. In the 1960s, many small

buildings across Ninth Street were cleared for urban renewal construction that didn't happen.

In 2003 the Washington Convention Center opened on the site.

Small houses, commercial buildings, and immigrant churches developed here after 1910. By the 1930s

the rich had moved on, and landlords divided mansions into rooming houses. In the 1960s, many small

buildings across Ninth Street were cleared for urban renewal construction that didn't happen.

In 2003 the Washington Convention Center opened on the site.

816 Third Street, NW

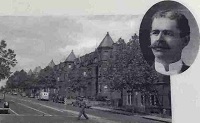

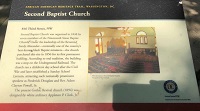

Second Baptist Church was organized in 1848 by seven members of the Nineteenth Street Baptist Church. Under the leadership of the Reverend Sandy Alexander -- eventually one of the country's best-known black Baptist ministers -- the church purchased this site in 1856 for its first permanent building. According to oral tradition, the building was a stop on the Underground Railroad. The church ran a children's day school after the Civil War and later established a Sunday School Lyceum, attracting such nationally prominent speakers as Frederick Douglass and Rev. Adam Clayton Powell, Sr.

The present Gothic Revival church (1894) was designed by white architect

Appleton P Clark, Jr.

The present Gothic Revival church (1894) was designed by white architect

Appleton P Clark, Jr.

The Maine Avenue Fish Market is the oldest continuously operating open-air fish market in the United States. When it opened in 1805, Washington was the center of the local fish and oyster trade. In the 1900s, it was known for the "jolly fish packers," and later saw the construction of the Municipal Fish Market. The seafood tradition carries on today with the barges and restaurants along the waterfront.

Originally constructed in 1809 as a mile-long wooden toll bridge connecting the District with Virginia, Long Bridge has seen many transformations and additions. In 1861, five days after the fall of Fort Sumpter, Robert E. Lee rode south on Long Bridge after declining command of the Union Army. In 1881, ice piled up against the bridge, causing an unprecedented flood that put 254 acres of DC under six feet of water and led to the creation of East Potomac Park.

Beginning in 1815, steamboats ferried passengers and goods across the river and connected the waterfront to Richmond and other points via Aquia Creek. Today's riverside activities continue to include boat day trips, excursions, and pleasure cruises on the Potomac. For boat owners and enthusiasts, the Capital Yacht Club, Gangplank Marina, and day piers offer a place to dock and partake in the excitement of The Wharf.

In the 1840s, the Southwest Waterfront was developing into a major commercial seaport and took on an industrial character. Buildings and warehouses were constructed to accommodate coal, ice, and lumber trades, as well as slaughterhouses, bars, and restaurants. Some of the earliest proprietors included J.S. Harvey & Co., "dealers in wood, coal, and groceries," as well as L.J. Middleton's ice business.

In April 1848, the largest slave escape attempt on record in the Unites States took place at the Southwest Waterfront. Seventy-seven men, women, and children boarded the schooner Pearl to sail to freedom, but were ultimately recaptured. The waterfront continued to play a role in antislavery activities of the Underground Railroad, with the Sixth Street wharf a meeting place from where slaves embarked for the north.

Private river commerce along the waterfront was disrupted during the Civil War when Washington became the headquarters and supply center of the Union Army. Wharves were appropriated for military purposes, and Water Street was opened and paved for military traffic. New wharves and warehouses were built along the waterfront to accommodate military shipping needs, and soldiers arrived and departed from the waterfront.

The Southwest Waterfront's history is closely tied to African-American history. Leading up to the Civil War many people of color - those still enslaved as well as some freed individuals - lived and worked here, and some helped build the original wharves. Later, the area's affordable housing and labor opportunities attracted thousands of newly freed slaves, and a close knit community with many rich and storied traditions developed along the waterfront neighborhood.

Before the 1800s, the Southwest Waterfront formed the eastern bank of the Potomac, but sediment accumulated as farming increased, making the river hard to navigate and prone to flooding. In 1882, plans to dredge the river were approved, with materials deposited on nearby mudflats, creating Potomac Park, thereby establishing the Washington Channel as well as the Tidal Basin.

Preparations for World War II ended plans of filling the Southwest yacht basins with pleasure crafts. Instead, a severe housing shortage during the war turned the waterfront into a home for houseboats, providing an obvious alternative for the many government workers who toiled in offices near the National Mall. Houseboats continue to be a permanent fixture at Gangplank Marina, a live-aboard residential community established in 1977.

Copyright © 1996 - The USGenWeb® Project, DCGenWeb