The History of Caroline County, Maryland, From Its Beginning

The Plantation

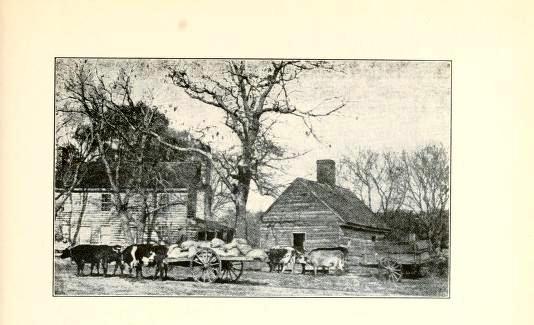

HOME OF BETSY BAYNARD AS A TYPE OF EASTERN SHORE SLAVE HOLDER

Looking backward to the days when forests stretched for miles over an

acreage now covered by fertile farms, we see about five miles N.E. of

Greensboro, some distance from the Eastern bank of the Choptank River, a

small clearing appear. Soon arose a small unpretentious building

typical of its day. Tall pines overshadowed it. At dawn the

song of the woodland bird awakened the sleeper, while during the hush of

eventide the call of prowling wild animals sent a thrill of fear through

the listener. Such in the 17th century was the beginning of the Baynard plantation—the

largest in the Greensboro section—extending over an area of more than

six hundred acres.

Time was in the early slave days when

tobacco flourished there, and Negroes, singing their weird melancholy

songs “toted” the tobacco to their storeroom. From thence it was

carried over the woodland road and delivered at the warehouse of William

Hughlett for even in the 17 hundreds the dense green of

Maryland pines had given way to the paler green of cultivated fields.

First the Baynards planted tobacco, but

later cereals formed the base of income; while in the last days of the

plantation, to these were added the returns from tanbark and railroad

ties.

In 1812 “Old Massa

Baynard” died and Mistress Betty,

then sixteen years old, became— under her mother—the Autocrat of the

Plantation.

The home with its rambling Negro

quarters had been enlarged and, while never ostentatious, held old

china, colonial furniture, a grandfather’s clock and other antiques such

as delight the eye.

There after her mother’s death Betsy Baynard lived

alone save for her house servant, Myna, and two

powerful dogs who stood guard day and night. Completing this

plantation community were her slaves who fill their huts to overflowing,

at times numbering more than two hundred.

Although not given to slave dealing,

at the time of enlarging her house to obtain the needed money Betsy sold

a servant “South into Georgia.”

“They say” the cartwhip was daily

used as a ruling power among her colored people but the blows must have

fallen lightly for many of her slaves remained contentedly on her

plantation until old and infirm, and when she died ten years after the

Emancipation some half dozen of her slaves were yet with her.

An amusing anecdote of the Baynard slaves

relates that a young Negro, returning from a dance, in the cold, gray

dawn went to the well for a drink of water. As his eye followed

the bucket on its descent he saw something white. True to race

superstition he believed it a spirit and ran to tell Miss

Betsy of “De hand in de well.” She returned with

him and found a sheep had fallen in and all but drowned.

A tragedy of the plantation was the

death of Miss Mary Reid, a cousin of Miss

Betsy’s, who at times made her home there. A slave girl, on

being reprimanded for some delinquency, took offense and attempted

revenge on Betsy by way of Paris green.

The poison miscarried, resulting in Miss Reid’s death

almost immediately.

As a memorial to the Baynard generosity

stands Irving Chapel. While the name is that of the first

minister, the plat of land on which Irving Chapel stands was donated

from the Baynard plantation, and the

lumber for the building was added on condition that the church members

cut it from the forest. Miss Baynard also

gave a sum of money, large in those days and sufficient for church

erection.

Betsy Baynard died without

direct lineal descendant. The land was sold in small sections, and

is owned principally by Rosanna Richards, G. W.

Richards, A. K. Brown and J. A.

Meredith. All that remains to recall the story of other days

is a portion of the old home which is yet in use by J.

A. Meredith, and a small family burying ground with three markers—

Written from material collected by Paul Meredith.William Baynard born 1769, died 1812.

Litia Baynard born 1773, died 1843.

Elizabeth Baynard born 1796, died 1873.