The History of Caroline County, Maryland, From Its Beginning

Life in Caroline Following the Revolution

Cleared farm land, on the average, was assessed at about $5 per acre, the wooded land about half as much. At this time there were recorded 290 slaves between the ages of 8 and 14 years. These were assessed at £25 (about $100 each). The 334 male slaves between the ages of 14 and 45 years were given a valuation of £70 ($300) each, while the 266 female slaves between 14 and 36 years of age were assessed at £60 ($250) each.

In addition to slaves, the personal property assessed consisted of silver plate, horses, oxen, and black cattle. There were returned as assessed 3750 horses in the county and 7946 black cattle, besides considerable silverware. The total assessment of real and personal property amounted to £247,000 or slightly over $1,000,000. It is clear, however, that property was assessed very low then in comparison with our modern idea of values.

Without any intention of being personal a few of the largest individual assessments will, perhaps, give the reader a clearer idea of the large land holdings at that time.

Thomas Goldsborough, at Old Town, was assessed 1148 acres of land of which 400 acres were cleared. In addition a grist mil and personal property brought the total assessment to £2630, about $12,000.

Thomas Hardcastle, at Castle Hall, about 1800 acres.

Benjamin Silvester, Oakland, 1200 acres.

William Whitely, 1500 acres.

Henry Dickinson, 1800 acres.

William Ennals, 2500 acres.

William Frazier, 1400 acres.

James Murray, 2800 acres.

Zabdiel Potter, 1012 acres.

William Richardson, 795 acres.

It will be understood, of course, that the above named persons were among the most prominent and wealthy in the county at that time. The rate of taxation was about one eightieth (1/80) of the assessed value or $1.25 per hundred dollars.

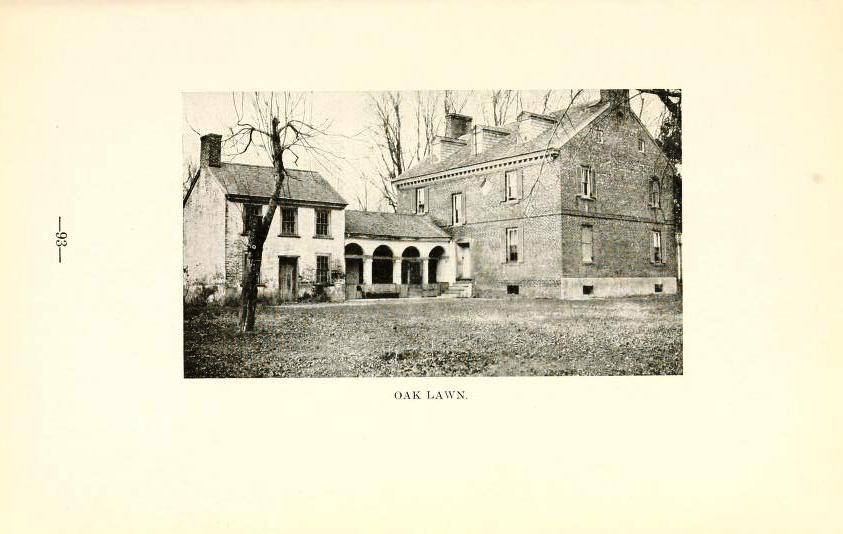

Before the Revolution there were in the county only about six or eight brick buildings. In the twenty years following the war, this number increased to approximately thirty. The reason for this increase may be explained in the following way.

The early settlers in the section had been thrifty folk, working hard and living simply. Their labors had been rewarded by flourishing crops of tobacco which had brought a splendid price in England. With the organization of the county there was a natural impetus to use this acquired wealth for the erection of more comfortable and permanent dwellings, but the close-following war delayed these plans. With the close of the war, however, these people as citizens of a republic felt new power within themselves. The hard, thrifty lives, no longer necessary, men at once started to make such changes in their mode of living as their financial conditions warranted.

The houses built during this period were substantially constructed and of similar design. The main buildings, three stories high with gabled roofs, had a lower wing built at the side which was sometimes of frame rather than brick. The walls were about eighteen inches thick, the massive doors of diagonal timber. So substantially constructed were these mansions, they might have been used as forts in time of siege. Many of hem have nobly withstood their worst enemy, Father Time, but others have been forced to yield to other enemies—fire and neglect. To better preserve these worthy structures, some of them have been covered with cement.

Mr. Tubbs, in his chapter on Caroline County in Colonial Eastern Shore, speaking of Cedarhurst and Daffin House, says what is true of all these dwellings:

“The doors, mantles and interior woodwork of these houses speak eloquently of the consummate art of the olden-time carpenters and joiners.”

The broad winding stairways found in many of these houses are no less tributes to their makers’ art. With the completion of these fine homes a gay social life sprang up in the county. Such houses were well adapted to the house parties, dances, and quilting parties popular in the early 1800’s. In winter the social and political life at Annapolis attracted many of the well-to-do people of the county, while in milder seasons fox-hunting, horse racing, and other outdoor sports were indulged in at home.

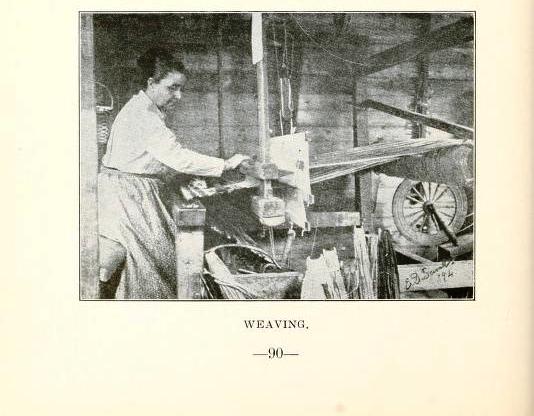

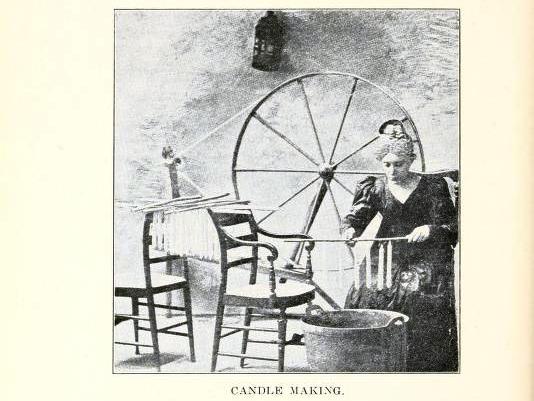

But life was not all merry making. The planters, though they usually employed overseers, daily rode over their plantations to superintend the work of slaves in the fields, shops and stables. On some of the plantations we find records of stores having been kept. The women, beside managing the household affairs, directed the spinning, weaving, knitting, and making of slave’s clothes. The actual work was sometimes done by the slaves, but oftener by women living in the neighboring villages and on small farms. An old account book from a plantation store credits a certain widow with knitting 3 pairs of men’s and 2 pairs of women’s stockings and weaving 30 yards of toe linen. The same widow is further credited “By making Billy’s breeches.”

The people during these years lived well. The smoke houses were filled with home-cured meats, while fertile fields supplied wheat, corn, and other necessary foodstuffs. The neighboring woods and rivers offered a supply of wild game, fish, crabs and oysters in season. From peaches and apples, pressed in copper stills, brandy was made.

Wheat bread was not commonly used. Except in the wealthiest families, corn bread was the custom. Johnny cake, made of corn meal, and plate cake of wheat flour baked on wooden boards set upon the hearth, seem to have been the favorite breads of the time. Tradition has it that so weary did the people become of corn bread that gradually the wheat acreage increased.

It is interesting to note the clothing worn by people of means at this time. The men wore tight fitting coats, cut to display their fancy waistcoats, knee breeches fastened with silver buckles, long light-colored silk hose, and low black shoes with silver buckles. For riding heavy boots replaced these shoes. Their soft linen shirts had pleated frills and were fastened at the wrist with silver buttons.

The women, not to be outdone by the men, wore gay colored silks with narrow low-neck bodies and long full skirts. Their shoes were dainty, low cut pumps which sometimes boasted high red heels. Of such splendid material were the clothes of that time made and so lasting the styles, we often find single pieces or entire outfits willed from one generation to another.

A simpler form of life was lived in the small frame houses dotting the villages and countryside. In these houses the kitchens with their broad fireplaces were the family living rooms. Over these fires the meals were cooked, near their warmth the spinning was done, and by their cheery light during the long winter evenings the tired family rested after the labors of the day.

These houses were meagerly furnished. Except for an odd piece or two, the furniture was made by the men of the family. Wooden or pewter plates, spoons and bowls were used upon the tables. The iron pots, kettles, hominy mortars, and candle molds were so highly prized as to be mentioned in the wills of their owners. Even upon the large plantations, china was rarely used in later years.

It is from these sturdy people that Caroline is largely populated now. Many of the prominent old families have no lineal descendants living within her borders. Their former mansions are left to uncertain fate, their family burying grounds unkept, their very names almost unknown.

(An account of the political conditions about this period may be found under the Life of Thomas Culbreth, given elsewhere in this book.)