|

Brief

History of the Wind River Indian Reservation

From

the Wyoming Blue Book vol. 4, 1991

The

Wind River Valley of west central Wyoming has provided a home

for Native Americans since prehistoric times. Archaeological

evidence gives indications that humans were living in the area

as far back as 5,000 years before the present. Who these early

residents were and their connections to modern day Indians

cannot be determined,but clearly the association of the

Shoshone tribe with the Wind River area is the most enduring.

Early Shoshone

Occupation

The

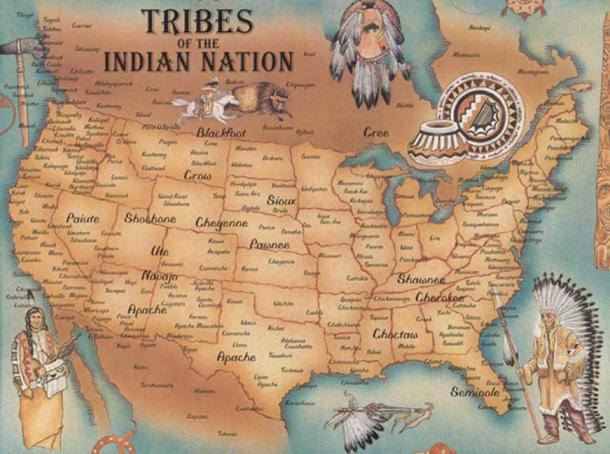

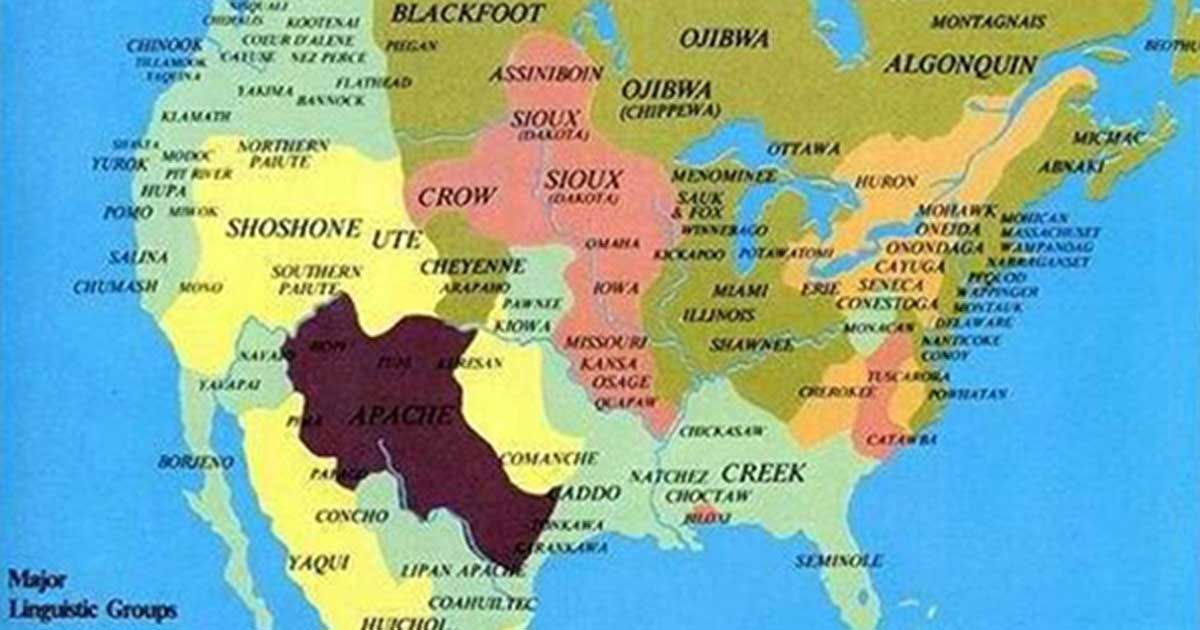

Shoshone tribe traces its origins to the Great Basin where they

were among the first of the Indian tribes in the region to

obtain horses through trade with the Spanish. Most reliable

research suggests that the Shoshone first began using horses

around 1700. Although they were already exerting their

influence east of the Rocky Mountains, the horse enabled the

Shoshone Indians to expand their territory across a broad

portion of the northern plains. Some researchers suggest the

Shoshone controlled the plains from the Arkansas River in

Colorado to the Bow River in Saskatchewan. They were clearly

among the first of the mounted buffalo hunting cultures.

But

the golden age of Shoshone domination was short-lived. Other

tribes-from the east and the north- moved onto the plains and

asserted their influence. And by 1800 the eastern most bands of

the Shoshone tribe were confining their activities to the

Wyoming and southeastern Montana areas. With the arrival of

Anglo-Europeans on the northern plains and in the Rockies,

diseases spread among the Shoshone and tribal populations

declined. By 1850, white emigration along the Oregon-California

Trails was having an impact on game herds and competition

between the buffalo hunting tribes of the plains increased. The

Crow, Sioux,Cheyenne and Arapaho people hunted the buffalo

herds of the Wind River Valley more frequently and the Shoshone

were increasingly found on the southwestern slopes of the Wind

River Mountains. Historical accounts from the 1860s indicate a

growing reluctance on the part of the Eastern Shoshones to hunt

east of the Wind River Mountains despite the fact that buffalo

could no longer be found west of the Wind Rivers.

Conflict and

Negotiations with Whites

1863 Fort Bridger

Treaty

The

destiny of the Shoshones had become closely associated with the

expanding non-Indian populations in the area. During the 1860s,

the Eastern Shoshone traded at Fort Bridger and became familiar

with the U.S. military forces in the area. They were frequent

visitors in the Mormon communities of Utah and southeastern

Idaho. Many accounts exist of contact between Shoshones and

travelers on the emigrant trails. In most cases, the

relationship between the Eastern Shoshone Indians and

non-Indians was amicable.

In

1863, following a conflict between the U.S. military and their

Idaho relatives, the Eastern Shoshone - under the leadership of

Washakie - entered into a treaty of

friendship with the U.S. government. The treaty acknowledged as

Shoshone country as a large area of land in southwestern

Wyoming, northwestern Colorado, northeastern Utah and eastern

Idaho; provided for the safety of travelers, settlements,

military out posts; and guaranteed a twenty-year annuity to

provide supplies for the Shoshone people as compensation for

the "inconvenience" caused by the establishment of

agricultural and mining settlements in the area.

1868 Fort Bridger

Treaty

Five

years later, as preparations for the construction of the

trans-continental railroad were underway, the U.S.

government needed to clarify land ownership so it could make

the necessary grants to the Union Pacific Railroad. There was

also concern about the threat of attack from the more

aggressive tribes roaming in northern Wyoming. A reservation

for the Shoshones in the Wind River Valley seemed to solve

several problems. What ever the motivations of the government

negotiators, Washakie was satisfied. The hunting was better

there and the government had agreed to protect the Shoshones

from attack by their Indian neighbors to the north.

Against

that back-drop, the U.S. Government and the Eastern Shoshones

concluded negotiation and on July 3, 1868 at Fort Bridger

signed the treaty that

created the Shoshone reservation. The treaty provided for

definite boundaries,a system by which individual tribal members

could select land for the development of farming skills,

educational services, annuities, and the establishment of a

military post.

The

military post, called Camp Augur, was established in 1869 on

the site where Lander is now located. A year later the post was

moved to the Little Wind River and renamed Camp Brown. The Wind

River Agency came to life nearby and soon the Shoshones were

establishing their lodges in the surrounding areas.

Early Years on the

Reservation

Some

historians say the early years on the reservation were good.

The first attempts at farming were highly successful, hunting

was excellent, annuities arrived on time, and the government

provided ample quantities of beef on a regular basis. But by

1874, agriculture was on the decline. Much of the land that had

been cultivated had gone back to sod and weeds. Hunting

pressure began to reduce the game herds.

The

most significant development on the reservation during the

1870s, however, was the arrival of the Northern Arapaho Tribe.

Early Arapaho on

the Great Plains

The

Arapaho Indians came to the plains from the northeast but

little is known as to when they arrived. Some of the earliest

references to the Arapaho place them on the Cheyenne River in

what is now South Dakota in 1795. As the power and population

of the Sioux tribes increased, the Arapaho drifted southward.

By the early 1800s, they are recorded as being concentrated

between the Platte and Arkansas Rivers. To offset the

advantages enjoyed by the Sioux, the Arapaho occasionally

allied themselves with the Cheyenne to hold their territory and

assert their rights to hunt the areas they considered their

own. The increasing competition for the available hunting

grounds was aggravated when non-Indian travel began in earnest

over the Oregon-California Trails. By 1850, such travel was

having an impact on buffalo herds and inevitably led to

conflicts between travelers and the Native Americans who saw

the effects on their ability to subsist in the country.

Conflict and

Negotiations with Whites

1851 Fort Laramie

Treaty

In

1851, more than 9,000 Arapahos, Cheyenne and Sioux gathered on

Horse Creek east of Fort Laramie for a treaty conference with

U.S. government officials. The agreement they reached called

for peace between the various tribes and with U.S. citizens.

The tribes also agreed to recognize the rights of the various

tribes to control certain territories. The Arapaho and Cheyenne

agreed to share the country between the Arkansas and the North

Platte Rivers. The treaty,

however, had little long-term effect on Indian-White

relationships. As emigrants increased in numbers, so did the

number of conflicts between Indians and whites. Buffalo herds

continued to diminish under pressure from white market hunters

and the 1859 discovery of gold in Colorado brought thousands of

new settlers to the region. It was during this time that the

bands which would become known as the Northern Arapaho began to

roam more frequently north of the Platte River.

In

1864, a group of whites attacked and slaughtered a camp of

Cheyenne and Southern Arapaho camped on Sand Creek in Colorado.

Word of the massacre spread to the northern tribes and in the

years that followed, the Northern Arapaho joined with the

Cheyenne and Sioux in open warfare against whites across

Wyoming, Colorado and Kansas.The Southern Arapaho eventually

could do little but accommodate the settlement of north-central

Colorado. In 1865 they accepted a small reservation in Indian

Territory (now Oklahoma). But the Northern Arapaho continued to

roam the Powder River Country of Wyoming, asserting their

determination to negotiate independently with the U.S.

government.

1868 Fort Laramie

Treaty

Those negotiations began

in 1868 at Fort Laramie. There the Northern Arapaho agreed to

settle on a reservation within one year - either on the

Missouri River with the Sioux, in Indian Territory with the

Southern Arapaho,or on the Yellowstone with the Crow. But the

Northern Arapaho wanted nothing to do with the southern

country, and they were leery of being over whelmed through

close association with larger and stronger tribes. So Northern

Arapaho leaders began to seek the assistance of army officers

to help them settle on the Shoshone Reservation in Wyoming.

Bates Battle

Prior

conflicts with the Arapaho made Washakie and the Eastern

Shoshone uncomfortable with such an arrangement and an 1869

meeting to discuss the placement of the Arapaho on the

reservation fell through. But in 1870, it was agreed that the

Arapaho could reside on the reservation temporarily. The

arrangement lasted only a few months. Whites in the Lander area

and in the South Pass gold fields blamed the newly-arrived

Arapaho for the killing of several settlers. A short time

later, a 250-man force of settlers and miners attacked two

Arapaho camps near Lander and once again the Northern Arapaho

were on the move. They resisted government efforts to place

them on various reservations until an armed conflict that came

to be known as the Bates Battle occurred in 1874.

The

main camp of the Northern Arapaho was located on the headwaters

of Nowood Creek north of present-day Lost Cabin when it was

discovered by some Shoshone scouts. Several days later, the

camp was attacked by a military unit from Camp Brown and a

large contingent of Shoshone Indians. Although the Arapaho were

able to escape, they lost a large number of horses and many of

their lodges were destroyed. It was the last time the Northern

Arapaho would fight the whites.

Shared Reservation

Arapaho Settled on

the Shoshone Reservation

The

next few years were a time of intense hardship for the Arapaho.

They subsisted as best they could while their leaders -

foremost among them were Black Coal and Sharp Nose - made new

efforts to obtain a suit able reservation. They focused their

efforts on establishing a friendly relationship with army

officers and began by enlisting as scouts for the military.

General George Crook interceded on behalf of the Arapaho and

attempted to secure a reservation for them on the Tongue River

but was unsuccessful. But finally in 1877, Arapaho efforts paid

off during a visit to Washington, D.C. and a meeting with

President Rutherford B. Hayes. That meeting led to an agreement

that federal government would assist in the negotiation of an

arrangement under which the Northern Arapaho could join the

Eastern Shoshones on their Wyoming reservation. The Arapaho

began arriving on the Shoshone Reservation in March of 1878 in

spite of the fact that the Shoshone had not yet given their

consent. While government officials continued to assure the

Shoshones that the Arapaho presence was temporary, Arapaho

leaders worked to solidify their position on the reservation

and Arapaho tribal members began establishing camps on the

eastern portion of the reservation.

Changes to the

Reservation

The

reservation they co-occupied with the Shoshone had already

changed from the reservation that had been established in 1868.

Gold miners and settlers had laid claim to lands in the South

Pass area and southern portions of the Wind River Valley before

the reservation was created and white settlement in those areas

continued in the early 1870s. The conflicts arising from those

claims led to the 1874 cession to the United States of that

portion of the reservation lying south of the North Fork of the

Popo Agie River. In return the Shoshones received $5,000 worth

of young cattle every year for five years. Washakie received an

annuity of $500 per year for five years. Known as the Brunot

Cession, this relinquishment of land was the first of several

significant changes in the shape of the reservation.

Pressure

for those changes came from white settlers who sought the

commercial benefits of Shoshone Reservation, 1874 larger

numbers of non-Indian residents in the area. Congressional

passage of the General Allotment Act of 1887 helped increase

that pressure.

The

General Allotment Act has been interpreted as a direct at

tack on the tribal culture by some. Others saw it as a means by

which individual Indians could move toward independence and

self-sufficiency. It allowed individual Indians to claim

specific acreages of reservation land. After a period of years

had passed, title to those lands went to the individual Indian

and the land could be sold or used at the discretion of the

individual. By 1890, non-Indian commercial interests in the

Wind River Valley were urging reservation agents to begin an

aggressive campaign to allot reservation lands. They argued

that quick completion of the allotment process would reveal

large tracts of "unneeded" reservation land, and that

such land could then be opened for settlement by non-Indians.

But there was limited interest in allotments among the 'Wind

River Indians and tribal leaders resisted attempts by

governmental officials to move the process ahead.

Sale of the Hot

Springs

The

next change in reservation boundaries came in 1897. For several

years nonIndians had been settling near the hot springs on

the Bighorn River north of Wind River Canyon. The springs were

located on the extreme northeastern corner of the reservation

but those non-Indians saw the commercial potential of the

springs and wanted to capitalize on it. Bowing to those

interests, the U.S. government sent an agent to negotiate a

deal. Eventually the Wind River Indians sold an area of about

10 square miles surrounding the springs for $50,000. Washakie

seemed happy enough with the deal but he objected strenuously

to the involvement of the Arapaho Indians in the

negotiations.

Allotment

of reservation lands began in 1898 and were pushed aggressively

following the turn of the century. In 1904 the U.S. government

met with the Wind River tribes again to discuss the cession of

largely unclaimed lands north of the Wind River. The ensuing

arrangement called for those lands to be opened for settlement

under the Homestead Act with al l proceeds to be paid to the

tribes for per capita payments, irrigation systems, and

education.

The

land opening came in 1906 and resulted in the establishment of

the town of Riverton along with the farming areas around

Riverton. The income derived from the opening of reservation

lands provided benefits that helped bring an end to a twenty

year period of poverty, hunger and privation.

Hard Times on the

Reservation

Buffalo

herds which existed in the Wind River Valley and the

adjacent Big Horn Basin had declined rapidly after the

settlement of the two tribes in the area. This reduction in

available game put pressure on the herds of cattle which had

come to the tribes as a result of the 1868 treaty and the 1874

Brunot Cession. By 1885, there were fewer than 100 head of

cattle owned by the Indians. While they struggled to develop

farming skills, tribal members became increasingly dependent

upon the rations provided by the government. Some

individuals were able to earn income by serving as scouts for

the military or on work crews for government projects. Many

credible sources, however, indicate that Indians were

frequently cheated in these arrangements. Occasional newspaper

accounts from the early 1890s claimed that Indians on the

reservation were starving, but government officials denied the

reports. There is no doubt about an 1897 epidemic of measles on

the reservation. More than 150 Indians died, most of them

children.

Education on the

Reservation

Education

on the reservation developed at a slow pace. The earliest

efforts were made by traveling teachers. In 1878 a day-school

was established. By 1886 a boarding school was operating near

the agency. At the turn-of-the-century most Indian children

were going to school but that was achieved only through

coercive measures. Educational efforts often were aimed

directly at eradicating tribal customs. Students were often

punished for speaking their native languages.

The

elimination of tribal customs was pursued also by reservation

agents. Among the most memorable measures took place at the

turn-of-the-century when H.G. Nickerson began changing

Indian names on tribal rolls to English-sounding names. Lone

Bear became Lon Brown. Yellow Calf's new name was George

Caldwell.

Religious Changes

Cultural

conflicts arose over religion as well. Episcopalian missionary

Reverend John Roberts came to the reservation in 1883 and began

work in the Fort Washakie area, primarily with Shoshone people.

A year later, Father John Jutz established a Catholic mission

in the area occupied by Arapahos which became known as St.

Stephen's Mission. Although the missionary efforts brought many

Indians to these white religions, native people struggled to

reconcile the teachings of those religions with their cultural

heritage. Within this context several native religious

movements developed.

The Ghost Dance

The

Ghost Dance phenomena of the late 1880s originated with a

Nevada Paiute named Wovoka. Wovoka revealed that he had died

for a time during which God told him to return to his people

and preach the doctrines of love and peace. He claimed that God

had also given him new words to the songs of the old Ghost

Dance. If these songs were sung while dancing, Wovoka taught,

white people would disappear and dead Indians would return to

life. Wind River Arapahos embraced the Ghost Dance with zeal,

but the Shoshone were more skeptical. When the predicted new

world failed to materialize, Arapahos began drifting away from

the dance. Others persisted and that led to the banning of the

dance by the reservation agent. But Arapahos continued the

Ghost Dance in secret for a number of years. Indeed, Wovoka is

reported to have visited the Wind River Reservation in 1910 and

an enthusiastic dance was held in his honor. Arapahos lined up

to shake his hand, paying as much as $20 for the privilege.

Peyote and the

Native American Church

Peyote

rituals came to the Arapahos from Oklahoma in the mid-1890s and

gained numerous participants. The Shoshones began to

participate in the rituals following 1910. The use of peyote in

religious rituals eventually achieved continuity after the

establishment of the Native American Church in 1918.

Indian

Reorganization Act

For

many years into the 20th century reservation governance

continued much as it had in the 1880s and 1890s. The

government's agents exercised enormous control over the daily

lives of people living on the reservation. Tribal elders

functioned as councils through which reservations residents

could participate in reservation governance, but most agents

attempted to use those councils to further their own agendas.

In the 1920s the Arapaho and Shoshone tribal councils began

meeting as a joint business council in order to develop a

coordinated approach to common concerns, interests and

problems. In the 1930s an effort developed to create a

constitution and bylaws under which the joint business council

would assume some responsibility for the governance of the

reservation. But it never received the blessing of Bureau of

Indian Affairs officials in Washington. Then in 1934 Congress

passed the Indian Reorganization Act and signaled a major

change in the way the federal government would deal with

Indians. The act offered reservation tribes who voted to accept

its provisions increased freedom to regulate their internal

affairs. But it also contained language regarding land

allotments which Wind River Indians found disconcerting and

both the Shoshones and Arapahos eventually voted not place

themselves under the provisions of the act. Instead, the two

tribal councils continued to work separately and in cooperation

to develop their methods of operation and gradually assumed a

greater degree of responsibility for the operation of the

reservation.

Court Suits and a

Name Change

The

1930s also saw the culmination of the conflict between the two

Wind River tribes which began when the Arapahos were settled on

the Shoshone Reservation in 1878. Omaha attorney George M.

Tunison had begun working with the Shoshones in the 1920s to

resolve their claim that the government had violated treaty

provisions by placing the Arapahos on the reservation. Finally,

in 1927, Congress passed an act which empowered the Shoshones

to sue the government. The case dragged on for more than ten

years until 1938 when Court of Claims awarded the Shoshones

more than $4 million dollars and legitimized the Arapahos claim

to half of the reservation. It was at that time that the

reservation officially became known as the Wind River Indian

Reservation.

Tribal Lands

Returned

A

year later the federal government acted to change the

reservation boundaries for the last time. It restored to the

tribes those lands north of the Wind River which had been ceded

for settlement in the 1904 agreement but which had not been

homesteaded by non-Indian settlers. The action left an island

of non-Indian land-known as the Riverton Reclamation

Project-within the exterior boundaries of the reservation.

Modern Era

The

modern era on the Wind River Reservation is highlighted by the

assertion of tribal sovereignty. Federal authorities have

encouraged the tribes' representatives to assume more

responsibility for their own affairs and the financial

responsibility for many reservation services. But while council

members have been ready to assume more authority they continue

to pressure the federal government to assume more of the costs.

They view federal services as treaty obligations, not charity.

|

![]()

![]()