Oconto

County WIGenWeb Project

Collected

and posted by Oconto County WIGenWeb Project

Collected

and posted by RITA

This

site is exclusively for the free access of individual researchers.

*

No profit may be made by any person, business or organization through publication,

reproduction, presentation or links to this site

.Copper Culture Burial Site.

Oconto County, Wisconsin

contributed by: Sarah

Baldueck -

from the family heirloom scrapbook

of her grandmother, believed published in the

Oconto County Reporter, date

unknown.

To

the Copper Culture Main Page

(Note: the time of this article's

writing is in the early 1950's, shortly after the site was discovered.

Scientific analysis has progressed tremendously since that time, and many

of the conclusions have undoubtably changed. The purpose of this posting

is to share these historic findings as of the time they happened - Rita)

13 Year Old

Donald Baldwin who discovered the Copper Culture

Burial ground in June 1952. |

Oconto County Reporter Reuben LaFave, Oconto County

Archeologist, Police Chief Henry Toole Oconto, and George E. Hall, President

of the Oconto County Historical Society inspecting relics at the Old Indian

Burial Grounds a short time after the discovery was made. |

THE OCONTO SITE

AN

OLD COPPER MANIFESTATION

By Robert

E. Ritzenthaler and Warren L. Wittry

Introduction

The purpose

of this preliminary paper is to present a descriptive report of a

recently

discovered Old Copper site on the western outskirts of the city of Oconto

in Oconto

County, Wisconsin. The importance of the site lies in the fact that it

is

only the

second instance of Old Copper artifacts found in situs with burials, the

first

being the Osceola Site in Grant County, Wisconsin, discovered and excavated

in 1945.

While Osceola added some important information to this little-known

culture

of Wisconsin, it was obvious that more such sites were necessary for

comparative

purposes and to expand the picture of the life of these early

Wisconsin

inhabitants. The Oconto Site provided valuable data along these lines.

It has

been generally believed that the Old Copper people were the earliest

Indians

to inhabit Wisconsin, and estimates run as much as 5000 years ago for

their

arrival. Their name is derived from the fact of their having made a

considerable

variety of tools and ornaments out of Lake Superior copper by the

processes

of cold hammering or heating and hammering. The copper artifacts,

most of

which have occurred as surface finds, are distinctive for their thick coat

of copper

salts and heavy acid erosion which suggest considerable antiquity.

The Osceola

Site (Ritzenthaler, 1945) showed that a-long with such Old Copper

artifacts

as socket-tang spear points, spuds, knives, awls, conical points, beads,

and bracelets

there occurred a rather distinctive chipped-stone industry. The

chipped-stone

work exhibited fine workmanship in primary flaking and secondary

retouching,

and included in its products a characteristic type of drill, scraper, and

point.

The points were consistent in having a lanceoate shape with rather parallel

sides,

side notching, and a concave or sometimes straight base. Two bannerstones,

of the

"bow-tie" and prismoidal type, found by amateurs at the site provide evidence

that they

also made ground-stone artifacts.

Their burial complex consisted of interment in a cemetery (no mounds) and

the

employment of the bundle burial method as most common, but partial cremation

was also practiced. Their type of implements indicate an economy based

on

hunting and fishing.

With this rather meager picture of Old Copper culture the Oconto Site was

approached. One chief objective was to obtain enough charred wood for a

Carbon

14 analysis as to accurately date this group. We were also interested in

getting

information on house type, ground-stone work, and in obtaining data which

could

be compared with Osceola in terms of burial practices, and types of copper

and

chipped-stone artifacts.

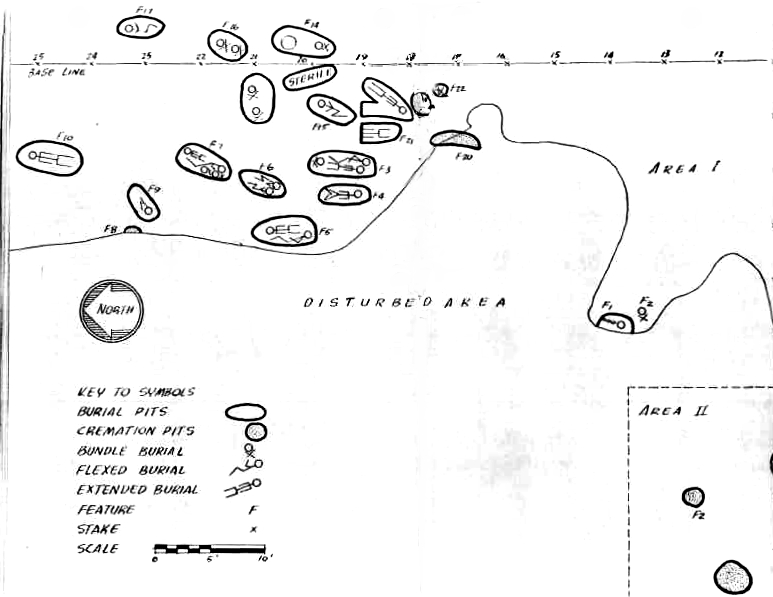

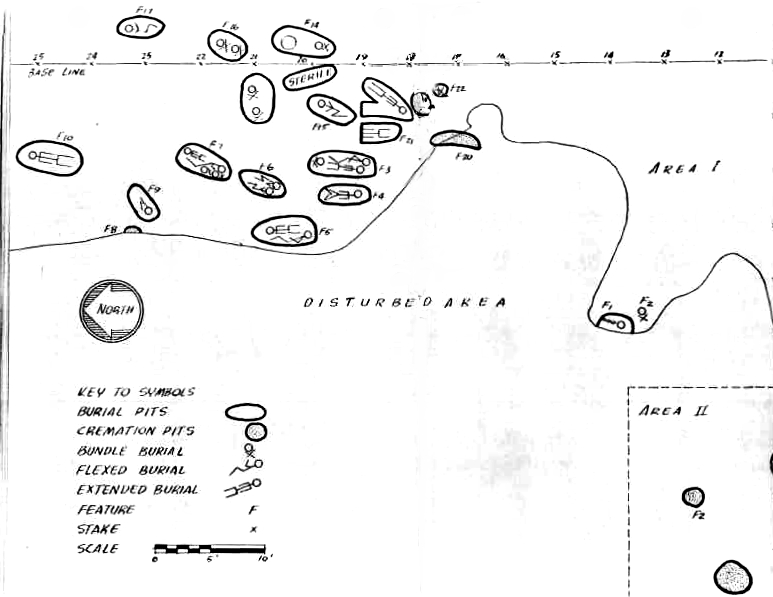

Diagram of the archiological

dig site

Diagram of the archiological

dig site

|

The Oconto

Site

The Oconto Site

was discovered in June, 1952, by Donald Baldwin, a 13 year old

boy, while digging

in an abandoned gravel quarry on the western outskirts of the

city of Oconto.

His discovery of human bones was investigated by Mr. Reuben

LaFave and Mr.

George Hall of the Oconto County Historical Society, and their

test excavations

revealed burials accompanied by copper artifacts. The find was

reported to

the Milwaukee Public Museum, and two members of the anthropology

department made

a one day trip to examine the site and artifacts obtained thus

far. Arrangements

were made to excavate the site, and on July 16th, Mr. Warren

Wittry representing

the Wisconsin State Historical Society, and Mr. Robert

Ritzenthaler

and Mr. Arthur Niehoff of the Milwaukee Public Museum arrived at

Oconto and began

work. The project was conducted as part of the program of

the Wisconsin

Archeological Survey.

General View of Site

General View of Site

|

The site lies within the western limits of the city of Oconto with the

burial area about 150 yards north of the Oconto River. Specifically it

is within Part 4 of Government Lot 8, Section 24 of Oconto Township, and

is now the property of the Oconto Historical Society. The area was formerly

a fairly level one1, but commercial gravel operations during the 1920's

removed and disturbed a large area and there is little doubt that a considerable

portion of the burial site was destroyed in the process. It is probable

that the burial site originally enclosed an area at least 100 feet square.

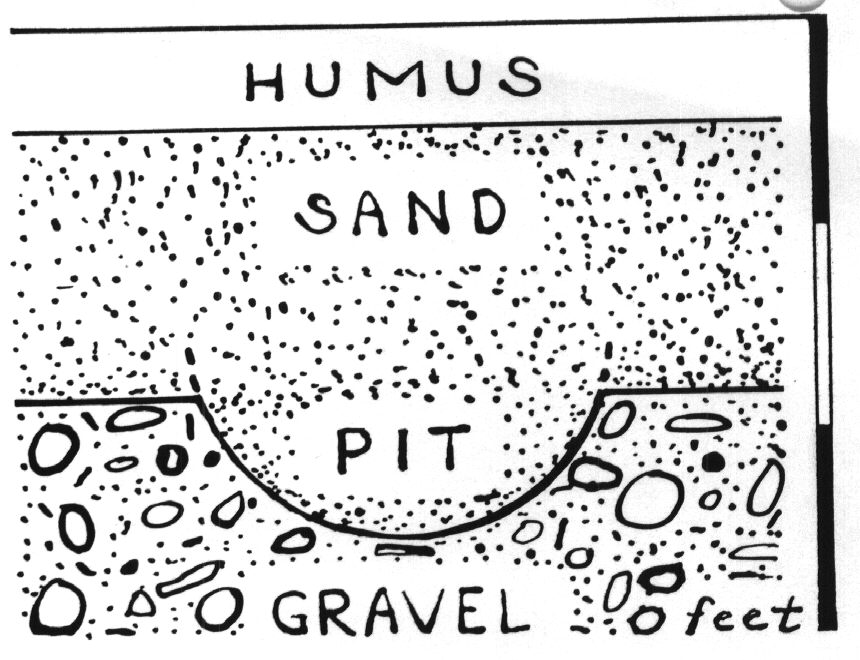

There is no indication of mounds. Beneath the eight-inch topsoil lie several

feet of Plainfield fine sand, underlain by gravel.

Method

of Excavation

A base line running north-south was established nd a five-foot grid system

employed. Excavation procedure was to strip a square rapidly down to the

bottom of the approximately eight inches humus layer which was sterile

except for quantities of sawn animal bones existing as refuse from a slaughterhouse

formerly located just to the east of the burial area. When the yellowish

sand lying below the humus line was reached, stripping proceeded more cautiously

as occasional copper implements (particularly awls) were found only a few

inches below the top of the sand layer. Near the bottom of the roughly

two foot deep sand layer, the burial pits would begin to show up.. The

burial pits were rectangular as seen from above, roughly two by four and

one-half feet in size, and basin-shape in cross-section.

They had been dug into the gravel, the burials laid-in and covered with

sand,

so the pits were discernible by the gravel outline when approached from

above.

The cremation pits appeared as roughly circular when seen from above,

basin-shaped in cross-section, and in instances did not penetrate into

the

gravel layer. Each pH was given a feature number.

The

Burial Complex

Nearly all the burials occurred in pits, and both burial pits and cremation

pits were

found. Eighteen burial pits were discovered, with one of these sterile.

Three

others had been discovered by Mr. LaFave before our arrival. While the

usual

size was about two by four and one-half feet, they ranged in length from

four to

eight feet, and in width from two to nearly four feet. The shape was rectanguloid

as seen from above, with rounded corners, sometimes to the extent of resulting

in

the outline being more elliptical than rectanguloid.

Feature 10 showing pit shaped and extended

burial

Feature 10 showing pit shaped and extended

burial

|

Feature 7 showing partial flexed burial with shull

of bundle burial near pelvis, and skull of child and two antler tips near

feet.

Feature 7 showing partial flexed burial with shull

of bundle burial near pelvis, and skull of child and two antler tips near

feet.

|

They were basin-shaped in vertical cross-section and from one to two

feet in depth. Most were "custom dug." just large enough to house

the individual or individuals interred. Of the twenty-one burial pits,

one contained nothing, eleven contained a single individual, seven contained

two individuals, one contained three, and one contained five. A variety

of burial positions were sometimes found to occur in a single pit.

In Feature 7, for example, there were three bundle burials, one partially

flexed, and one extended. In the two instances in which the secondary burials

occurred in the same pit with primary ones, the secondary burials were

above the primaries. Apparently the individuals who died in the winter

were kept until the spring thaw made digging possible. Then the recently

dead were interred in the flesh and the bones of those left over

from the winter were thrown on top as secondary burials. In eight of the

pits one or more artifacts were found, but there was no consistent or significant

position of artifacts in relation to the skeleton.

Feature 5 Double burial in pit showing

whistle at back of head of child (left - center)

Feature 5 Double burial in pit showing

whistle at back of head of child (left - center)

|

The bone whistle, however, lay at the back of the head of the child.

(See Webb, 1950, p. 291, for a similar occurrence.) Thirteen of the pits

were orientated with the longitudinal axis running in a roughly north-south

direction, but there seems to be no significance to it, as some had an

east-west orientation and others fell somewhere in between. Furthermore,

there seemed to be no pattern as to how the individuals were faced. A total

of seven cremation pits were discovered plus one reported by the LaFave

excavation. They were roughly circular as seen from above, and basin-shaped

in vertical cross-section. Their diameters ranged from two to four

| Method |

Number of Individuals |

| |

certain probable |

| Extended |

9 (2 of these were prone positions) |

| Partially flexed |

4

3 |

| Fully flexed |

3

1 |

| Bundle |

12 |

| Partial cremation |

8 pits (number of individuals un-known) |

| (Unidentified) |

5 |

| Total |

45 individuals |

Physical type:

A study of the skeletal material has yet to be made, but it is

readily apparent that they were a fairly robust group, of average stature

for Wisconsin Indians, but with well-developed musculature. The state

of bone preservation ranged from fair to very poor.

Evidence of Occupation

Besides the cemetery there was little in the way of evidence of occupation.

Copper implements, particularly awls, occurred sporadically in the upper

levels of the sand layer and bore no apparent relationship to the

burials. Four chipped-stone points were found apart from an association

with burials. It is probably that they represent lost or discarded items.

Numerous post molds were found and mapped, but no discernable pattern was

apparent. A considerable number were of consistent size usually 8 feet

in diameter, and in some cases three or four would line up with fairly

consistent spacing and direction, then abruptly end. Fragments of charcoal

were found in two of the molds. The end product was a map showing

such disorderly scattering that no resemblance of a wall or house

could be ascertained.

Artifacts

A detailed

list of the Oconto specimens with description, measurements, and association

appears as Appendix A of this report. This section will concern itselfwith

a summary of the types found and comparisons with Osceola materials.

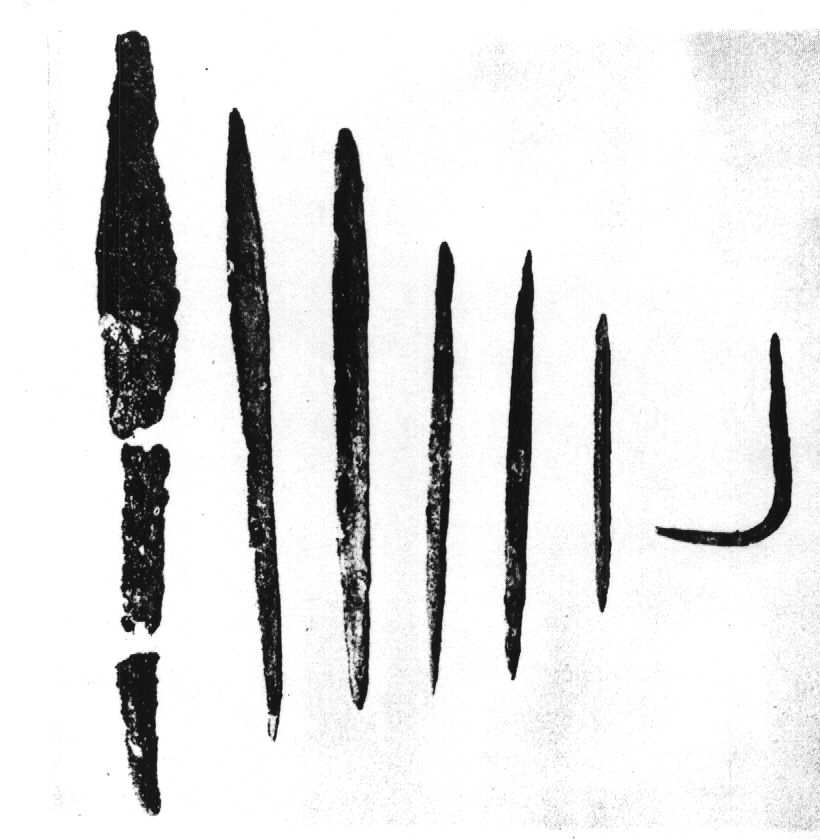

Copper:

Oconto yielded fewer copper artifacts and fewer types than Osceola.

There was a total of 26 specimens found, including those dug by local

residents and turned in for measurement and photographing.

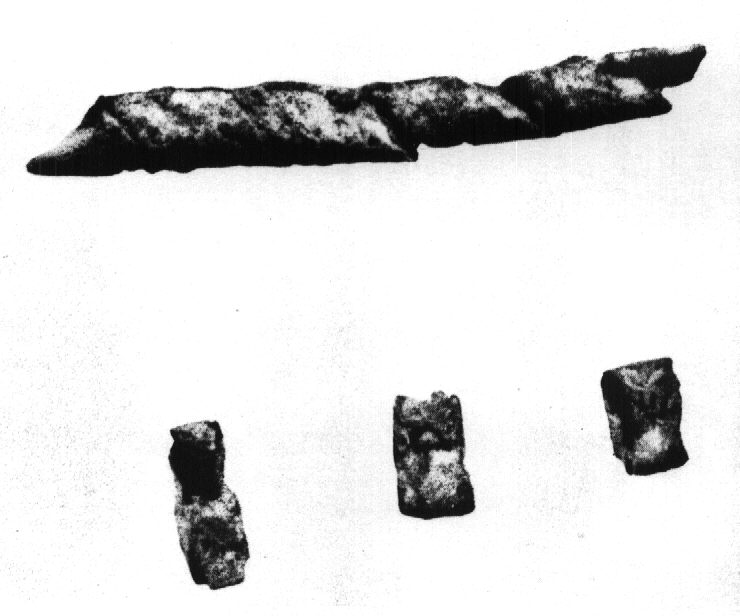

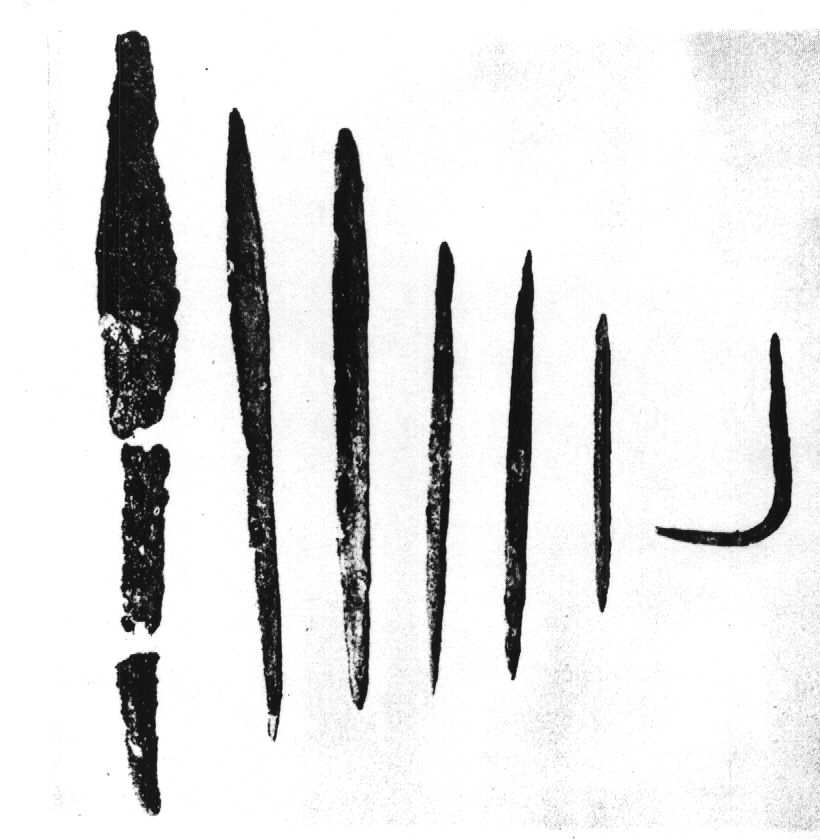

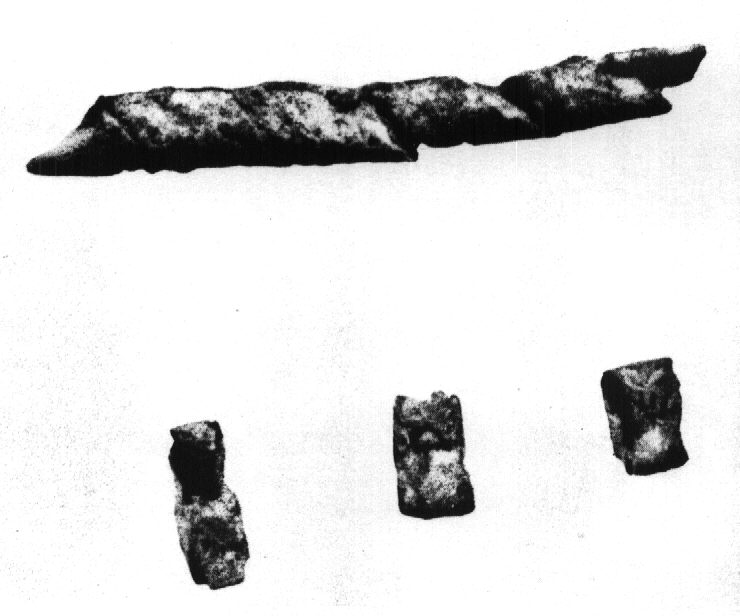

AWLS

AWLS

|

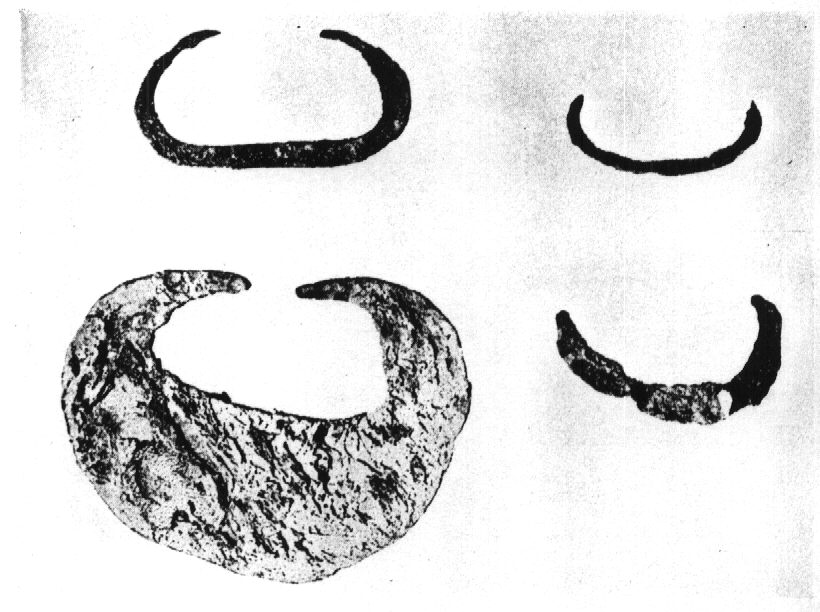

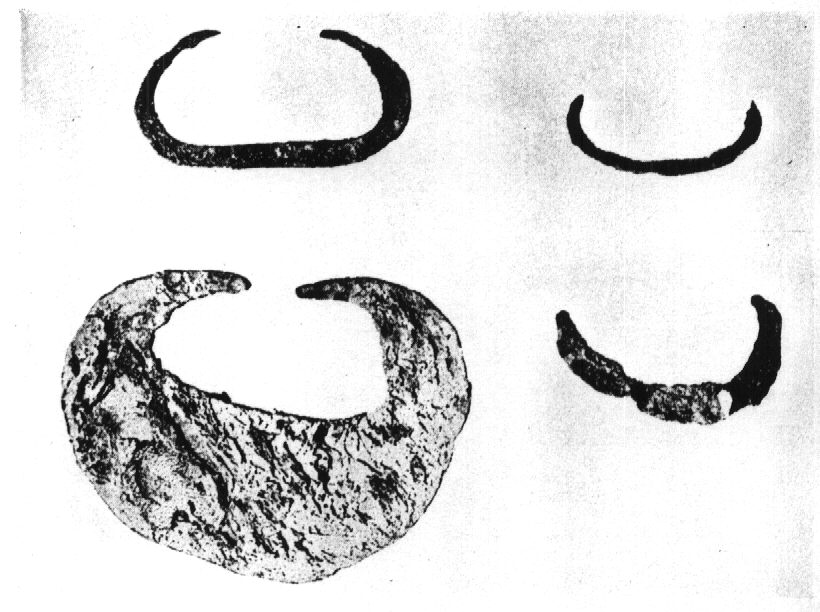

FOUR CRESCENTS

|

THREE CLASPS (bottom)

|

BRACELET

BRACELET

|

PIECE OF SPIRAL-COILED TUBING

(top)

|

SPATULA (right), FISHHOOK, RIVET (left bottom), and

4 UNIFENTIFIED PIECES

|

The types are listed as follows:

Seven awls , four crescents, three clasps, and one each of the following:

spear-point with broken tang, fishhook, bracelet, section of spirally-coiled

tubing, rivet, and spatula. There were also four small unidentified

pieces.

As with

Osceola, awls were the most numerous type of artifact, but the Oconto specimens

were of smaller size.

Crescents were more numerous at Oconto, but in contrast with Osceola no

spuds were found and only one socketed-tang spear-point. At both

sites utilitarian products were much more numerous that the ornamental.

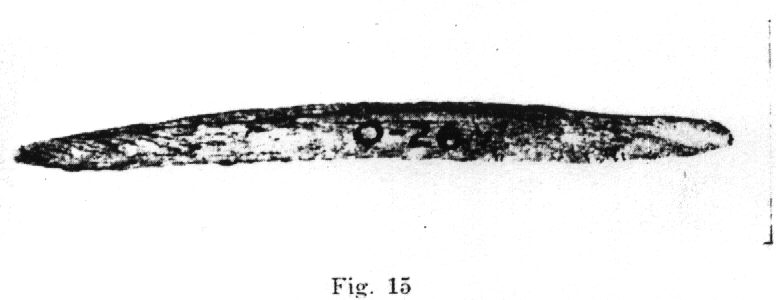

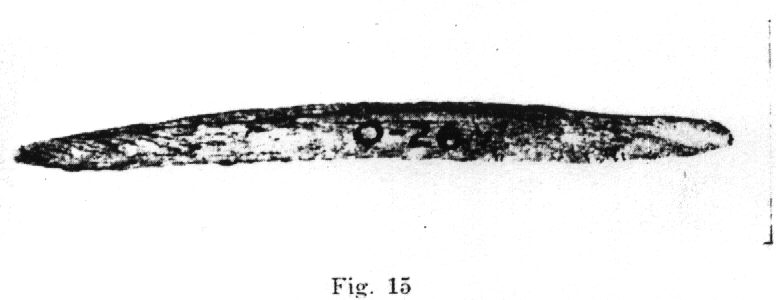

Chipped

Stone

TWO PROJECTILE POINT (top)

TWO PROJECTILE POINT (top)

SCRAPER (bottom)

|

Somewhat surprising, in contrast to Osceola, was the paucity of chipped-stone

implements. A total of seven such artifacts were found, with only three

being associated with burials. Of the remaining four, one, a straight-stemmed

point fragment, occurred in the humus layer and could represent a different

culture, one was found in a disturbed area and stratigraphy could not be

determined, and two were near the top of the sand layer. All were projectile

points with the exception of one, a triangular scraper found with a burial.

Of the two points found with burials one was triangular in basic shape

with the side notches, but the sides of the blade appear to be re-chipped;

the other was ovoid with a straight base and side notches. The latter

was the nearest in type to the Osceola type, but none were characteristic

Osceola points. Besides the variation in type, the Oconto points

were smaller, none being over two inches in length. Like Osceola, however,

the technique of primary flaking with secondary retouching along the edges

was employed.

Bone:

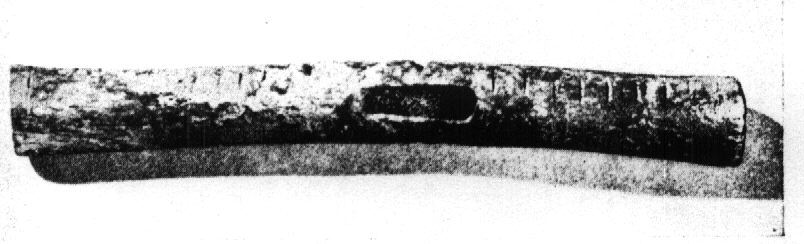

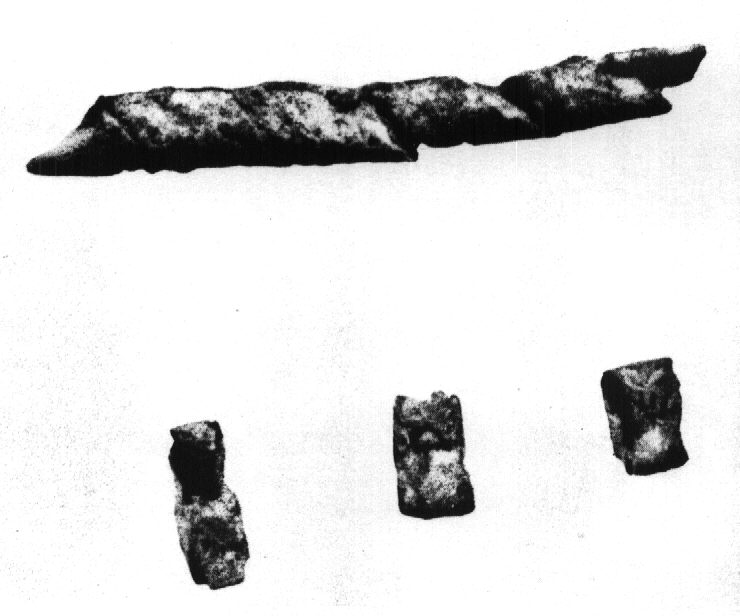

WHISTLE

WHISTLE

|

AWL

AWL

|

Two bone artifacts were found, the first bone Implements to be associated

with the Old Copper complex thus far. The most interesting was a fine specimen

of a whistle made from a leg bone of a swan. It was six inches long with

a rectangular opening near the center, and three rows of

short, incised lines running the full length as decoration. The

second specimen was a awl 2 5/8 inches in length and made from a

portion of a fish jaw.

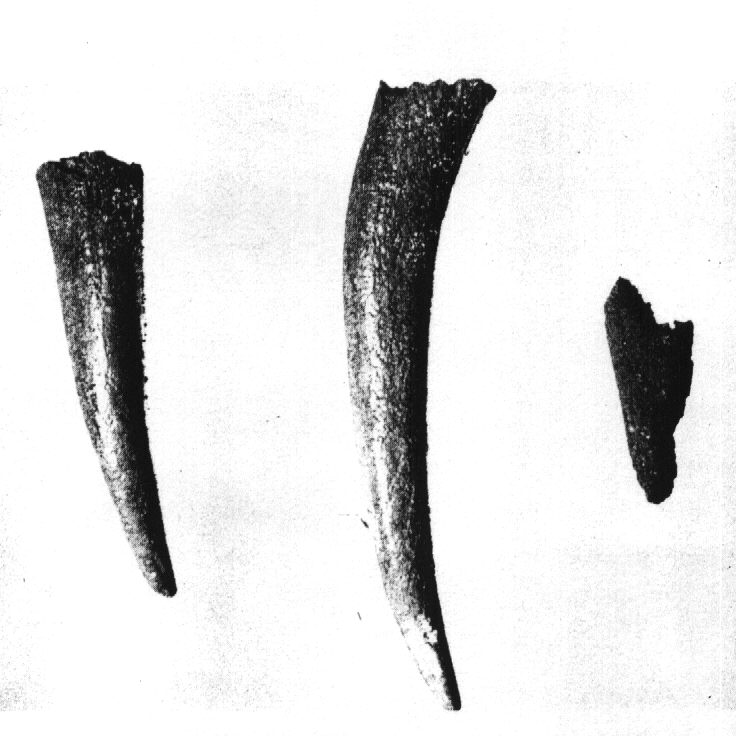

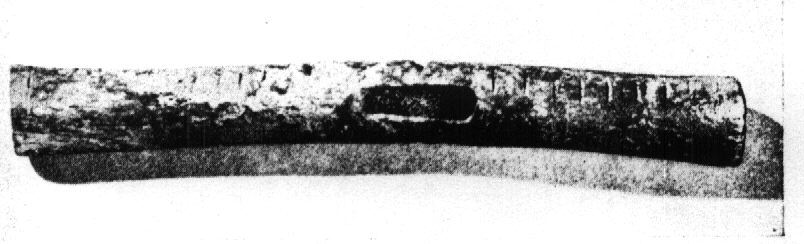

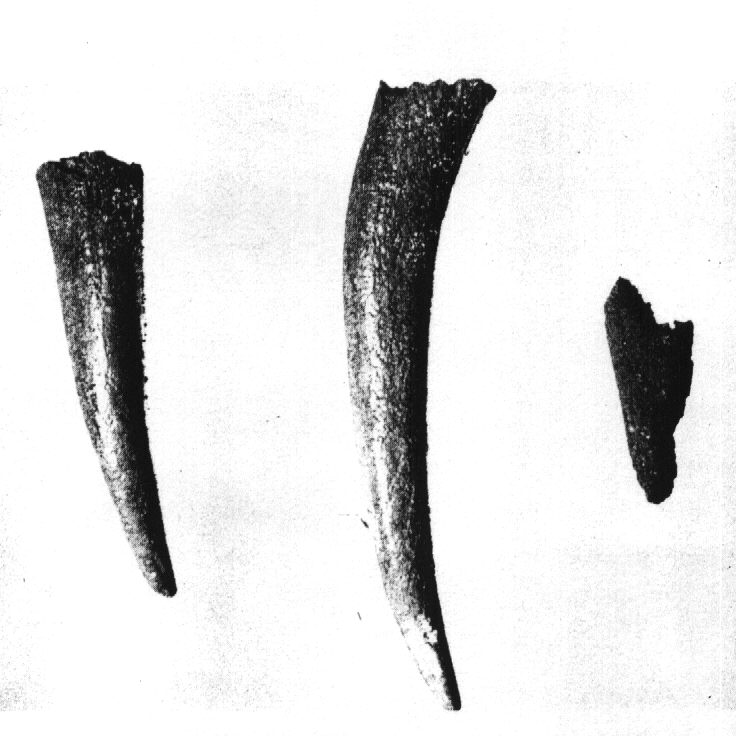

Antler:

ANTLER TIPS

ANTLER TIPS

|

Two well-preserved antler tips, suitable for use as flaking tools although

the polished ends gave no indication of such use, were found together in

a burial bit. A third specimen, a charred short end-section occurred in

a concentration of charred wood.

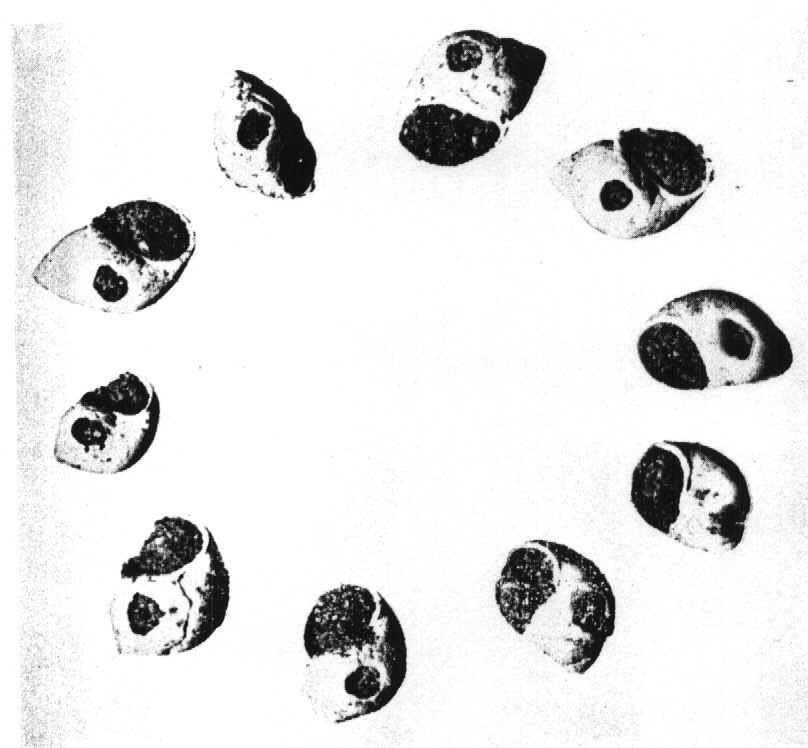

Shell:

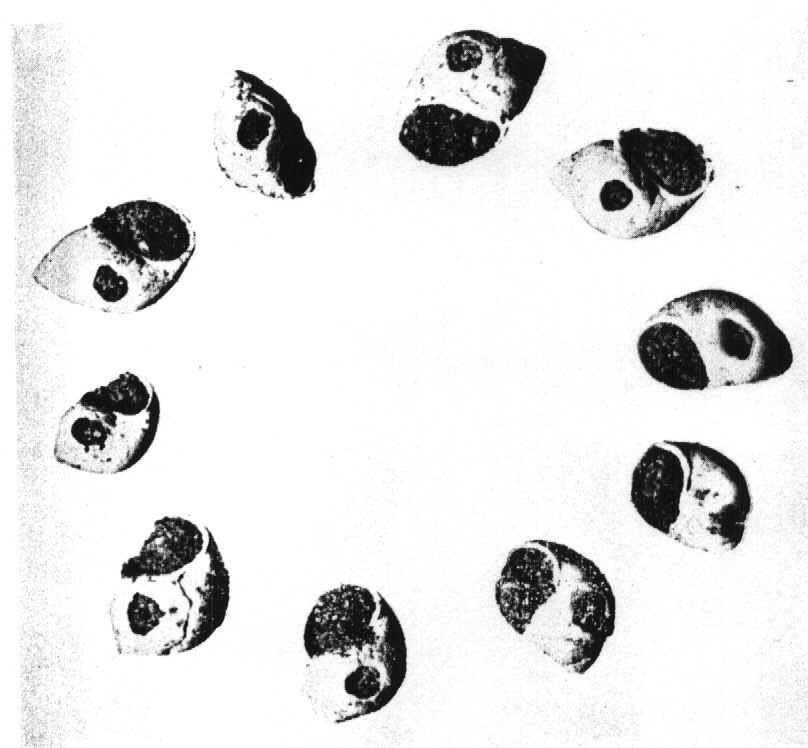

POND SNAIL BEADS

POND SNAIL BEADS

|

A series of 14 pond snail (Campeloma decisum) beads plus fragments of

several more were found with a burial before our arrival. They were reported

as occurring at the wrist of the skeleton and apparently 1/8 inches in

diameter near the center with the stringing presumbably done through this

hole and the natural aperture.

Portions of two unworked shells were also found in a burial pit. One was

a

fresh-water clam {Unio ellipsis), the nearest present source of which is

the

Mississippi River. The second was part of the shoulder of a large lightning

shell, a

type of whelk (Fulgar perversus) the present distribution of which is the

Atlantic

Coast from North Carolina to Florida. It was from a shell originally about

a foot

in length, and its importance lies in its indication of trade or contact

with a region

over a thousand miles away.

Hematite:

Two lumps of iron ore were found near the head of the extended child burial,

with which the bone whistle was found. A rounded facet, apparently of natural

origin, appears on the smaller of the two.

Pottery:

No pottery

was found.

Animal

Remains:

Near the

head of an extended burial in a pit, Feature 4, were found a number of

small

bones. They were indeati-fied as parts of turtle and a duck (unidentified

as

to species

but about the size of a mallard).

Conclusions

While the

Oconto and Osceola sites are obviously closely related in culture and

must be

considered as belonging to the Old Copper Culture, it is also apparent

that

there

are a number of differences between the two. The variation is most strongly

evident

in the chipped-stone types, but the differences also exists in terms of

types

of copper artifacts, burial methods, bone and antler work, and polished

stone.

To a considerable

extent it is merely the absence of a trait, such as bone work for

Osceola,

that creates the difference, and it is very possible that what we have

here

are inadequate inventories of the culture at both places. Future excavation

might

fill in these gaps to the extent that such negative variations will cancel

out.

The variations apparent at this point could be theoretically accounted

for on either

special or temporal grounds, or both. Considering the special approach

the two

sites are at opposite ends of the state some 210 miles apart as the crow

flies. If

contact were lacking, the variation could easily occur within a relatively

short

period of time. As to a temporal difference, there is no evidence to indicate

either

that one is older than the other, or that they were contemporaneous. It

might be

noted that Oconto is near the heart of the Old Copper center as indicated

by

distributional studies based on surface finds (Wittry, 1951, pp. 14, 18)

while

Osceola exists as a lonely outpost, but it is impossible at this point

to determine

which group was the earlier.

Concerning

the problem of dating, there was nothing at either site to dispute the

theory that Old Copper represents an archaic horizon in Wisconsin, and

that these

were the earliest Indians to occupy the site. The Oconto site, in fact,

bolsters this

theory because of such evidence as the absence of pottery and the bone

whistle of

a type found in archaic sites outside the state (see Ritchie, 1944, p.

294, and Webb,

1946, p. 305). As for more precise dating, enough charred wood was obtained

at

Oconto for a carbon 14 analysis and it is hoped that the forthcoming analysis

will

provide the answer to the problem of the age of the Old Copper culture

in Wisconsin.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

* Ritchie, William A., The Pre-Iroquoian Occupations

of New York State. Rochester Museum Memoir No. 1, 1944.

* Ritzenthaler, Robert E., The Osceola Site. Wisconsin

Archeologist. N. S. Vol. 27, No. 3, Sept. 1946.

* Webb, Wm. S., Indian Knoll. University of Kentucky

Reports in Anthrop. and Arch., Vol. 4, No. 3, Part 1, 1946.

* 覧覧覧覧覧覧覧, The Carlson Annis Mound.

University of Kentucky Reports in Anthrop. antl Arch., Vol. 7, No. 4, 1950.

* Wittry, Warren L., A Preliminary Study

of the Old Copper Complex. Wisconsin Archeologist N. S. Vol. 32, No. 1,

Mar. 1951.

BACK

TO THE OCONTO COUNTY HOME PAGE