In Lynden there lives one of the oldest settlers of Puget Sound; a man who crossed the plains at a time when it took time and bravery; who has lived to see his chosen country develop from a forest-covered wilderness to the richest section of the nation and whose heart is still young - N. V. SHEFFER. This old man, who has been longer in the state than the much renowned Ezra MEEKER, and who can count four generations of his off-spring peopling this valley, has a wealth of recollections of early days and people that is interesting in the extreme. We had planned to visit him - for he is old now and comes up town only at long intervals, but never got around to it, until by luck we got acquainted on the picnic grounds Saturday. He readily consented to meet us and tell something of his interesting life, the first installment of which follows: "Though I am a good mathematician and a fairly good writer I only attended school three months. The rest of my education is the result of digging in later years, since I came to the coast," Mr. SHEFFER said in an apology when we were looking over his notes he had made last winter. His remark was unnecessary for his writing was better than that of the average high school student. He started his story: "I was born in Indianapolis, Sept. 18, 1825. It was there I first met Ezra MEEKER, when he was only a slip of a boy, for he is much younger than I. We lived in Indianapolis until I was 10 or 12 years old, when my parents went to Williamsport, Ind., where I grew to manhood on the banks of the Wabash river. "My father was a carpenter. I worked with him from when I was big enough to turn the grindstone until I was a man grown, and until I was considered a very good carpenter. "It was in the spring of 1850 that I started for Oregon, with two yoke of oxen and one yoke of cows. The company with which I started was overloaded, and made slow progress. We were harassed by Indians, and a number of the party died from the cholera which broke out in our train. It was getting late in the season when we reached the summit of the Rocky mountains at South Pass. The train was demoralized and I was afraid it would never get through. Myself and the owner of three other wagon concluded to cut loose and make for Salt Lake, which we did, the main train taking to the right and we to the left. I have never heard anything of those who stuck to the main trail from that time on. We made very good time after leaving them and reached Salt Lake safely. It was our intention to go on to California over the Sierra Nevada mountains, crossing near the Humbolt lake, but we were informed, in Salt Lake that it was too late in the season. They said we might get over the mountains on snow shoes, but that we couldn't take the stock through. "There was a train of Mormons going south to reinforce a colony which LYMAN and RICH had established at San Bernardino, Cal. We got permission to travel with them and had a very pleasant time, with the exception of one snow storm that caught us at the rim of the great basin at what afterwards became famous as the 'Mountain Meadows.' The snow fell to a depth of 14 inches, but one day's travel down the mountain put us out of it and out of winter travel. There was a captain or president of the trail and a captain to every ten wagons and all of the captains acted as council or cabinet. Every thing was conducted in perfect order. There were guards and stock herders and every man in the train did his turn. We had very little trouble from Indians and seen none after we left the waters of the Rio Virgin. We crossed the deserts without suffering for either man or beast. When we got to the Mohard, generally a dry wash, we found a raging torrent. It delayed us several days but we spent New Year's Day, 1851 in San Bernardino. "Our party stopped in the settlement for only a short time. I had started for Oregon - all this country was then Oregon - and my compass pointed this way. Me and my party struck out up the coast. We found some good traveling and some very bad, almost impassable - one place in particular, in a canyon, we were three days making eight miles. Some places we had to take our wagons apart and carry them part by part for some distance. But our men as well as our women were of good metal, and we made it - because we had to. It was a happy day when we arrived at the mission of San Jose. We could see the Bay of San Francisco, and some shipping. Mr. ROBINSON and myself had become pretty short of money, clothing and provisions. In a year on the road our families had worn out their clothes, shoes and things, and learning that the wagon road over the Shasta mountain was not yet completed, we disposed of our oxen and wagons, keeping the cows, and went to work for John M. HORNER. Wages were good - $4 and $5 a day. After we finished HORNER's house we got a job across the bay at San Raphel. Mr. PARKER agreed to move us over, he having a large boat. He took the whole show at one load - both families, five cows and all our dunnage. After finishing PARKER's hotel we bought some lots and built us some houses to live in. Work was not so plentiful so we went to San Francisco - only about three hours sail - and worked there a few months. "We saw so many coming out of the mines with big purses of gold dust that we got the fever. We left our families at home and went up the Yula River and started mining. There we remained until July 1854. A young man named BURDOCK was one of our neighbors. He often visited our cabin. He never tired of talking of Puget Sound which had just been cut off from Oregon and made a part of the new territory of Washington. He was very anxious to go there and he revived the old Oregon fever in me, and we agreed to take first boat from Frisco that we could get. He went to Frisco to arrange for our passage and I went home to get ready. I left my family with Mr. and Mrs. ROBINSON, where I knew they would have proper care. "I do not remember the exact date of leaving Frisco. Our trip on the ocean was a new experience to me. I was not sick as is usually the fate of inexperienced travelers, but Mr. BURDOCK was sick from the time we started until we arrived at Port Townsend, and was inclined to return without taking a look at the country, but after a few days ashore he had recovered his spirits. "We arrived in Port Townsend about the middle of September. The weather was fine and the few white men there were very friendly. There were only 10 or 12 man and 3 women. Frank PETTIGROVE and F. B. HASTINGS had their wives with them and there was a young lady with the HASTINGS family who afterwards married Alford PLUMMER, the original locator of the land on which the principal part of the town lay. "We heard favorable reports of Bellingham bay, of the country round it, and of a coal mine that was being opened there. We determined to see it. We hired an indian of the illustrious name, George Washington, who had a good sized canoe, but he and his partner were as ignorant of the English language as we were of Chinook. For a small consideration we hired an interpreter named No-Nosed-Charley, he having had his nose bit off in a fight. He lived with the white people most of the time and could talk English. In fact during the Indian war he was a great help to the citizens of Port Townsend. "When we got our blankets and provisions and guns and the five of us ready for embarkation the canoe was brought around. It looked to me like the load would sink it, but it was able to take loads three times as large with perfect safety. We came around the lower side of Whidby (sic) Island and followed up the coast until we were near where Anacortes is located now, when we struck across through the islands for Bellingham Bay. "We landed at the mouth of Whatcom creek. There was a large number of Indians around the bay - some of them at Squalicum and sehome and where Fairhaven was afterwards located by Dan HARRIS. They lived in houses constructed of slabs or boards split out of cedar timber. I saw 15 or 20 men but only one white woman that I remember of, and that was Mrs. ELDRIDGE. "We stayed at that camp three or four days, looking at what country we could see. It was all a dense forest down to the water's edge. The Indians told us there was a large lot of land without timber at Samish and we got some Indians at Sehome to take us up there. (Our Indians had gone to visit the Lummies at the mouth of the Nooksack.) "We found the prairie at Samish as we had supposed it would be, nothing but an extensive salt marsh, interspersed with innumerable sloughs. BURDOCK was looking for farming land. He said the idea of clearing a farm in the timber made him sick at the stomach. I was looking for a place where I could work at my trade, and believed that I had found it. I believed that Whatcom was bound to be quite a town. "When we left Samish we went to the mouth of the Nooksack where we found our Port Townsend Indians. The Lummies told us, through our interpreters that the Indians grew quantities of potatoes up the river. BURDOCK wanted to go see. We had to change our canoe, and take what is called a shovel-nose canoe, one that is propelled by both paddles and poles. "On the trip up the river we saw a white man, some where near where Ferndale is now, but got no information from him that was of any value. The second day we came to a big jam, about three-fourth of a mile above where the beautiful town of Lynden is now located. We would have had to make a portage if we had gone further up the river, and so we decided to go back. We had failed to find any potato farms. We saw where someone had started to build a cabin on the north bank, near a swampy prairie, which was the only sign of a white man's work that we saw on the whole trip. "When we got back to our camp on Whatcom creek where we had left some of our things with an old gentleman who had a rough cabin, we were glad to be there. I think he was working for Henry ROEDER. It was raining and we got in with him. I don't recall his name but we stayed with him for several days. We had plenty of provisions and fish and game were easy to get, so we were in no hurry to get away. "One day we were lounging about the camp when we noticed a commotion among the Indians. Charley and our other Indians came running up and told us to hurry and get into the canoe - that the northern Indians were near and they they were very bad and maybe come to that camp - maybe go to Port Townsend - that they must hurry and take the news. "They did hurry. It was raining and the wind was blowing. There was a Whidby island Indian went with us to carry the news to his tribe. He left us this side of the island and cut through the woods. The Indians were stripped almost naked and worked as I never saw them work before or since. They did not seem to mind the cold wind or rain. The waves in the open were running high and they made the canoe leap from one to another. Night overtook us when we were out about an hour and a half. How they kept their course I do not know, but morning found us close to Whidby island, and our speed did not seem to diminish. We wanted to stop and get some breakfast. The Indians made us understand that we could stop is we wanted to but that they would go on without us, and that settled the matter, of course. "We arrived in Port Townsend cold, tired and hungry and sleepy, but we had changed our minds about the sea-worthiness of an Indian canoe, for it had been a terrible trip over the waters of the strait when they were at their worst. There were times when the waves seemed to be hills on both sides of us, and it seemed certain we would be swamped, yet we always managed to be on top. "I will confess that I had partaken of little of the fright of the northern Indians. We had no arms except my rifle and BURDOCK's shot gun and we would have stood poor show in standing off a fleet of canoes such as they used to bring when they came on one of their raiding trips in those days. I heard afterwards that the scare arose from a party of Indians who had been in Victoria on a trading expedition and had stopped at Simeano (sic) on their way back north. They had whiskey and were bad enough at such a time." Part II Mr. SHEFFER's story last week of his trip up the Nooksack in 1854 to look for reported Indian potato fields reminds one reader of the Tribune that such a field was supposed to have existed in a spot now included in the GALBRAITH place just across the river from Lynden. Arthur SWIM says that vines similar to potato vines were found in an alder covered spot near the river, and that they had small tubers at the roots. The theory is that the Indians had a small field around a camp there in an early day and that it had since grown up and potatoes grown wild. Mr. SHEFFER this week called the Tribunes attention to a news item from Bellingham telling of finding a petrified post while excavating for a new building in Bellingham. He says that in the early days there was a coal mine under Bellingham, and he believes the petrified post is a piece of one of the mine timbers. The mine shaft went down below sea level and when it was abandoned it is presumed that it filled with water, and it seems natural that some of the mine timbers might have become petrified. When SHEFFER and BURDOCK had rested up aafter their return to Port Townsend with the report of invasion by Northern Indians, they began to plan a visit to Olympia. He says: "I was staying with Mr. HASTINGS. He told me it would be cheapest for us to buy a canoe and paddle ourselves to Olympia, so I got him to buy one for me. I was then the owner and captain of my own vessel of transportation. We bought a 20-foot square tarpaulin that could be used as a shelter tent, and we also got a lot of advice. The latter (most contradictory) we bottled up for future use. "We still had a lot of provisions that we had bought in Frisco and we stored them in the canoe. The most cumbersome of our luggage was my tools and we took them out of the chest and wrapped them in bundles covered with cedar matting made by the Indians. "We set out for Olympia and intermediate points, paddling our own canoe. I think we touched at every place of importance on the route, and we made few mistakes for inexperienced navigators. We soon learned to travel with the tide, and not against it which is an important lesson in life. I had learned a little Chinook and by using my few words and many signs we were able to make ourselves understood by the Indians whose camps we stopped at. As a rule the Indians were not beggars, but they were great traders and would barter for anything we had. We could tell when we were near one of their camps by the smell of dried salmon. "On the third or fourth day we reached Seattle, then a little village of not more than 25 while people. We got acquainted with the leading men -- YESLER WILLIAMS or WILLIAMSON, who had quite a store, and DENNY, who lived over the hill about a mile away. Of these gentlement I will tell you more later on. Most of the white men on Puget Sound then, whose wives were not with them, had Indian women for housekeepers, clam diggers, etc. "We stopped there long enough to get what information we wanted about the course to Olympia. By that time the novelty of paddling had worn off and it was only hard work - BURDOCK was a good worker and we got along very well. We learned the main channel to Olympia and started out again. "There was no trouble in procuring game -- ducks, pheasants and deer were plentiful and could be had without much bother or delay. "When we passed where the city of Tacoma now stands there was no sign of white man or white man's habitation that we could see. At Steilacoom there was a sort of trading post that formerly belonged to the Hudson Bay company, but we did not stop there. "The weather was bad. It rained most of the time, and I began to feel like I would like to quit the life of a navigator and spend a little time in a house where I could be dry a part of the time at least. "When we got in sight of Olympia the tide was going out so we made for camp for the night. The next morning when we got up the tide was going out again, and it kept going out until we began to think the Sound was going dry. We had to wait for the incoming tide to float our boat. When we finally reached Olympia we tied up to a log wharf covered with a flooring of split timber. There was quite a number of houses there probably 20 or 30, two stores, a school house, a black smith shop, and a saloon. "It was in Olympia that I met the first Governor the territory ever had. A first I was presdisposed against him because he was a democrat and I was a whig, but I soon got over my party prejudice. If ever the right man was in the right place it was Isaac I. STEPHENS. "After finding a boarding place which was not hard to do, we went into the country visiting Chambers prairie and the country adjoing. We stayed over night with Nathan EATON. He was a batchelor but at that time there was a family living in his house while preparing one for themselves. The man's name was WHITE, and the family consisted of a wife and three or four children. You will understand later why I am describing the family. "We spent several days in that neighborhood where there were several families. They had built a school house which they also used as a church. "There were a number of untaken claims that were just as good as those already occupied, but I don't think Paradise or the Garden of Eden would have satisfied BURDOCK then. He had had too much canoe too much rain and as they say in Alaska he had cold feet, and it was California for him and nothing else. Winter was close so we concluded to take the next boat for San Francisco. "While waiting for the ship one day I went to Tumwater, distant about a mile from Olympia. There was a saw mill there and I noticed it was not cutting as it should cut and told the owner so. He stopped the mill and let me look it over and I told him what was wrong. His mill wright had gone to Oregon for his family and he wanted me to fix it for him. "I had gone to his house to eat dinner with him. I told him I could fix it all right but I didn't know as I would have time as I was waiting for the ship to go to California. "You aint goin' to do any such ____ ____ think, you are going to fix my mill, was his retort. "At first I didn't know what to think of him. He went on talking and insisting that I was going to do the work and told me he would send a boat to Olympia for my tools and blankets. "I informed him that I could bring them up in my own canoe and it was at last agreed that I should work of the mill until the boat came, for I would have plenty of time to get down to Olympia and get aboard after the cannon wwas fired which always preceded the sailing of a vessel. "I soon discovered that I had found a diamond in the rough in my new friend, for such he was. Everybody, high or low, rich or poor, found the same generous welcome at his fireside and table. He was in reality the pioneer of Puget Sound having cut and hewn the first road for the first wagons from the Columbia river to the tide water on the Puget Sound. No man ever went to him for help and came back empty handed. Many an early settler was tided over by him until able to help himself and no tongue can discribe nor mind scarcely concieve the worth of such a man to a struggling pioneer neighborhood when starvation stared us in the face a third of the time, when we were out of flour and had no meat except that we hunted for. No woman or child ever went without the necessaries of life if he had knowledge of their necessity. Such was my rough diamond -- Mike SIMMONS. "But to go back to my work I brought up my tools. He offered BURDOCK a place in his home while I worked but BURDOCK preferred to stay where he was, and when I got my tools was the last I ever saw of him. "The next morning I went to work in the mill. We expected the boat in about three weeks. After ten days we went deer hunting, along the edge of Chambers prairie. We got a deer but when I got back I found the boat had come and gone and with it my partner. SIMMONS laughed and told me he had told me I would stay and fix his mill, and indeed there was nothing else to do except to keep at work. "I soon got his mill in satisfactory order and did some other work for him. Then I worked some in Olympia. Mr. EATON, before referred to came to get me to do some work on his farm. While I was out there another boat came and went. "I was considerably dissappointed, I wanted to go get my family and get back and settle in Whatcom before another summer, but it was not to be. "I made arrangements to do down Sound to Seattle or Port Townsend, where I would be sure and catch the next ship. There was a man with the uncommon name of SMITH in Olympia - half shoemake and half carpenter - who wanted to go to Seattle, and together we embarked in my canoe once more. "There had been some talk among the settlers of a general unrest among the Indians. They were growing sulky and impudent and would often appropriate things that did not belong to them. When Mr. SIMMONS bid me good-bye, at Tumwater, he told me to keep my eyes open for war canoes, and though I thought little of the warning, it is a lucky thing that we encountered none. I had never seen one then, but I have seen them often enough since. "On the way to Seattle we passed the mouth of the Puyallup as far distant and as quietly as we could, for the the banks under the hill where the city of Tacoma now stands was a large encampment of Indians. "Luckily we got off the main channel on the way to Seattle and missed the runners from up Sound who were on their way to Seattle and other of the down sound camps to warn the settlers of the outbreak of the Indians, so received the news only after we had reached Mr. DENNY's place at Seattle." Part III It will be remembered that Mr. SHEFFER had arrived in Seattle just as the news of the Indian outbreak was being carried from post to post. He continues his story: "Mr. DENNEY gave me a warm welcome. So did the other whites though they were not so warm as that kind-hearted gentleman. After the greeting the situation was explained. "I saw that it would be madness for me to attempt to make Port Townsend alone. There were many camps of the hostile Indians between the two posts, and they would be looking for lone canoe travelers. I moved my things into Mr. WILLIAMSON's store, it being about the handiest place, and he being very willing. It was then that I learned of the first outbreak, that had caught my friends on the prairie near Olympia, unprepared. "The Indians had made their attack on Sunday just at the close of the services in the Eaton Schoolhouse, before mentioned. "Mrs. CLARK and another lady whose name I have forgotten and some children had come to church in EATON's cart. The men had walked. After services, Mr. CLARK, after lifting the little folks into the cart, untied the horse and was still at its head while his wife was getting in when the Indians made their sudden attack. "Mr. CLARK fell dead at the horses' head. Though the women were both in their cart, they didn't have the line and the horse released from control, as if knowing just what to do started on the run for home, probably saving the lives of the women and children. The men, who were all armed, without the women to protect made a gallant fight and soon had command of the situation. "That the attack was premeditated was shown by the fact that hostilities began at the same time at all the other posts and settlements. A few Indians about Seattle did not join the war pary. One of them was Curley Jim, father of the Indian woman who lived with Mr. YESLER, the locator of Seattle townsite. During the trouble which folllowed Curley Jim and other friendly Indians were of considerable assistance, bringing in fish of various kinds and clams when our stock of provisions began to run low. "The settlers were gathering in from all direction, and at once we began the construction of a fort or stockade to protect them. In that, I being a carpenter found plenty to do. "There were so many things happening in such a short time that it was impossible for me to recollect them in the order they transpired. Then too there has been so much printed about this Indian war, in the newspapers and elsewhere that are not as I recall events, that if I should tell them as I remember them it would be a direct contradiction in many cases. Therefore I will only relate things that occurred, in which I was a participant, or which came directly under my observation. Probably I will not get things in their exact order, but as the events come to mind. "There were some very good men in and near Seattle and they were equal to the emergency. First there was a preliminary organization and then almost at once there followed enlistment and military organization. I did not enlist, for I intended to go after my family at the first opportunity and didn't want to tie myself down to serve and length of time, and could not have gone otherwise without deserting - it was a mistake on my part, however. "Although not regularly enlisted I did duty just the same and became man of all work. I was always ready to volunteer in any expedition and consequently when men were wanted to go to COLLIN's place, up on the Duwamish river, with Maj. J. J. H. VAN BOCKIN, of Port Townsend in charge I went along. About that same time the mail boat came and went on to Olympia, and I was determined that I would go on her after my family when she returned. But when she came back Governor Isaac I. STEPHENS came with her, and we learned that he had previously declared marshal law, and I was informed, politely, but firmly that I could not go aboard the boat or leave the territory. Consequently I, not very reluctantly, became one of the brave defenders. I was disappointed and a little bit mad at first, but I didn't know what at or who at, so I sneaked back to COLLIN's and the major with his everlasting stock of good humor and wit soon had me in a tolerable frame of mind. I fell into the rotation of duty once more such as working on the block house all day, and standing guard half the night. "But, the block house was soon finished and it then became monotinous. When anyone had to go to Seattle I was chosen. Dispatches, requisitions, reports or anything else that required dispatch found me always ready, and many times I went without any particular business. Maybe I was a little foolhardy but I didn't feel the fear on the Indians that many manifested. I often heard it remarked in the stockade that the Indians would not kill Mr. DENNY or me. Mr. COLLINS was a whole souled man and done and offered everything that was in his power to do or give for our comfort. Mrs. COLLINS was a kind motherly woman who tried to make everyone feel at home, and the daughter, Lucinda, about 16 years of age, was a good help about cooking. The three constituted the family. "One day when I was at the Seattle fort, Mr. DENNEY was going over to his place, which he did every day or two in spite of protestations, and I proposed to go with him. We were about half way and I was in the lead when Curley Jim so suddenly appeared in front of me that it startled me for a moment and I threw my gun to my shoulder before I recognized who it was. He put up his hand as a sign for us to stopo and approached Mr. DENNEY. In a low voice he told him there was a large number of strange Indians all through the woods that had come from the other side of the mountains to help the salt water Indians kill off the whites. DENNEY did not appear to be much frightened but we made schedule time back to the stockade. "Jim was much excited for an Indian, when he left us. I guess he had an idea that it was all up with the Bostons, as the Indians called the white men, and the news we carried to the camp caused no less excitement among those in the place. "With an escort, for they wouldn't let me go alone, I immediately set out for the fort or blockhouse at COLLINS' place and we arrived safely. The news created a considerable flurry I remember that Mr. COLLINS had always contended that Jim was a spy, but when he found the friendly Indian the first to give us the information that the Yakimas had arrived and were surrounding us, he changed his mind. "The news caused us to increase our watchfulness if that was possible. All during the war we were ever careful and alert, taking every possible precaution to guard against attacks, to which I attribute the few killings in and around Seattle. s "During the war and at about this time the U. S. man-of-war Decator cast anchor in the bay off Seattle and spread her protecting wings over Seattle. I think she had eight guns, if I remember aright, three on each side and one aft and one in the bow - all cast iron cannons. They looked awfully good in those days though I suppose they were laughing at us now. "The Indians were pressing us pretty close and it was considered the part of widsom to put the women and children aboard the war ship. I was in Seattle that day. Mr. YESLER's woman did not take kindly to the idea of going on the ship to live, but was at last prevailed upon to do it on account of the baby girl of which the father was very fond. YESLER was a good man, never making himself conspicuous, never crowding himself forward, but his opinion or advice when given was generally about right. He was not married to the Indian woman but when his wife came he did not do like many others, drive the girl back to her tribe. He provided for the Indian woman and looked out for her welfare and for that of his daughter by her. He gave the daughter as good an education as circumstances would permit. I had the pleasure of meeting the daughter about two years ago. She is married to a very nice gentleman who is one of the foremost citizens in the city and county where they live. She is a perfect lady and is respected by all who know her. Mrs. YESLER, when she came and found Mr. YESLER the father of the little daughter, took the little one to her home and treated her as her own child. "There were many noble men and women among the first settlers, for it took a brave noble spirit to face the trials, troubles, privations and dangers that were encountered from start to finish. It seems to me that the self-sacrificing spirit for the good of others, has degenerated into selfish greed. Some look upon us old pioneers as an encumbrance, rather than as the instruments through which a kind Providence has made it possible for them to be here today. They call us old moss-backs. Yes we are 'old moss backs' and we are proud of the moss. Would to God that they could grow a crop of moss on as self sacrificing backs, but I am afraid that it would not sprout - that it would find no nutriment and that it would wither up and blow away. I don't think they would stand the privations of the old moss backs. "Except fish and potatoes, provisions were hard to procure. No meat and no grease such as lard, tallow or butter. Very little flour and sometimes none. It was potatoes and fish for breakfast, fish and potatoes for dinner and so on around until the small of boiled or roasted fish raised my gorge. About the time Maj. VANBOKLYN was sent over to Port Townsend. He found a vessel there that had come for spars or piling and, of course, went on board. Being a good talker he prevailed on the captain to let him have a few pounds of salt pork and a few pounds of firkin butter. He asked for lard or tallow and the captain told him he had none. The cook overheard the conversation and reminded the captain that there were two small barrels of broken up dip candles down in the hold. The captain protested that the major wouldn't be likely to want anything like that, but the major assured him he would be very glad to get the broken candles and so he was presented with them. "The major got his candles ashore, had them boiled, the wicks pressed out and the tallow made up into cakes which he brought back with him. He was very exact in issuing the tallow so that it would go around, and it was every particle eaten with thankfulness. The major eat his share of it though I don't think he generally let the others know where the tallow came from or in what condition he had found it. It made fish taste different and potatoes go down smoother and it greased the griddle for our flap jacks. The pork and butter went to the women and children, as they were at all times our chief consideration. "As soon as Uncle Sam's boys in blue began to arrive things took a change for the better, for Uncle Sam's boys have a knack of having provisions with them or following close after. Then we were able to get sugar, tea and coffee, which had been almost unheard of luxuries. Everything was put under stricter rules too, and I was not allowed to run around so much as I had been. Still I was obstinate about enlisting and had to endure a good many jibes. "I finally had my problem solved for me. I was advised that as I could not go to my family I had better send for them to come to me. I wrote for them to sell our property and to come to Port Townsend. I informed Mr. HASTINGS of what I had done and asked him to look out for them when they came. "That was an easy way to think of, but in the performance it was tedious for first they had to sell the property, then the deeds had to be sent to me for signature and it all took several months. "During that time I remained at the COLLINS block house helping all I could and getting to Seattle infrequently, so I did not get acquainted with many of those who came in late. I knew a few of them by sight, but not by name, and I don't see how many of them could have known me by name, for I was called 'Indianna' by everyone. "If we had been prepared to prosecute the war more vigorously in the beginning it might not have lasted so long, though there would possibly have been more fatalities. The Indians had an idea they could starve us out, but when we began to receive quantities of supplies by large vessels that they could not attack in any hopes of success, and seeing as reinforced by regulars they began to understand the hopelessness of longer fighting. They were poorly supplied with provisions, their foraging grounds were limited as we kept them from their fishing grounds as much as we could. They got poor in flesh and were no longer very troublesome, because they had to spend most of their time hunting for something to eat. "There were numerous rumors about the circumstances leading up to the treaty of peace, some of which were true and some were false, but anyway brought great rejoicing when it was finally officially announced. At once there was great preparations to go to many deserted homes -- on the part of those who had homes left, and preparations to build new ones where the Indians had destroyed the old. It was in those days that such men as Mike SIMMONS, Nathan EATON, of Olympia, YESLER, DENNEY, WILLIAMSON, of Seattle, L. B. HASTINGS, PETEGROVE, of Port Townsend and ROEDER and ELDRIDGE of Whatcom showed their worth by extending helping hands to those in need. There were others as generous but they did not come under my observation. Everyone was so anxious to get away that they scarcely took time to bid their friends good by. __ waited a few days for the major to finish up his work, as he and another man accompanied me in my ever ready canoe to Port Townsend. We carried all of our traps with us and were as happy as men could be. When we arrived in Port Townsend we found all of the settlers gathered and we ___ a great jollification." I was now ready to go to Whatcom which I decided to make my future home, but as the mail boat was about due, I decided to wait for news from the family. My news came in a lump. Instead of the letters I was expecting, my wife and family all arrived. There was another jollyfication and a lot of visit all around and then I took the folks for a visit with some of my friends on Whidbey Island. While I was waiting around Port Townsend I got acquainted with some Army officers who were preparing to build a fort near the post. My wife had brought so much furniture up from California that I could not move it all in the canoes, and as there was no other way I had to get some of it stored. I then hired one Indian to help me with my canoe and Indians to take another canoe load and we moved to Whatcom. Mr. FITZHUGH gave me the privilege of building near the mine and also gave me some assistance. It did not take long to get a home enclosed so we could live in it, for I worked almost night and day. After we moved in I kept on working making it warm and comfortable. One day there was a ship came to anchor in the bay, and some of the men I noticed wore Uncle Sam’s uniform. The superintendent went down to meet them and was taking them to his headquarters by a path that led by my cabin. I was at my bench and I recognized Major HALLER [probably Granville O. HALLER] who stopped to speak to me. He remarked that I was doing my own carpenter work. "That is my trade, and I don’t know anything else," I told him. He replied: "How would you like to go back to Port Townsend and work on the Government fort? You would receive $4.50 a day and rations." I asked him how long he was going to remain in Whatcom, but he did not know and so I told him I would think it over and let him have my answer that evening. I talked the matter over with the superintendent of mines. He advised me he couldn’t pay those wages and that it would be best to accept them for the wages and rations were equal to $5 a day. The next morning I told the major that I would go back with him if he would get my goods down to the ship. I left my furniture with FITZHUGH only taking my stove, dishes, and bedding and such wearing apparel as we would need. I also had to leave my canoe which was like leaving an old friend. We were two days and two nights making the trip, but everything was very comfortable on the ship. We landed at the fort that was to be, and I was soon at my new work. The quartermaster was Lieutenant R. N. SCOTT. He was a young man of very good qualities, but if Maj. HALLER had any good streaks about his make up they didn’t show themselves very often. He and I got along alright but we never said anything to one another. When we met we would pass with only a military salute. After we settled to work the lieutenant came to my quarters and told my wife that he wished her to wash a few handkerchiefs for him, so that he could enroll her name as company "laundress." She could then draw rations. My wife agreed to it and after that we drew rations together. As the Quartermaster Sergeant was a nice Scotch laddie we got all that was or ought to be coming to us. I stayed with that job until June ‘58 at the time of the Fraser River excitement had taken all the citizen mechanics from the fort, and Bellingham was booming. I likewise got the fever and quit my job and brought my family back to Whatcom. We found my house occupied but Mr. FITZHUGH soon cleared it for me, as it was some of his men. Mr. ROEDER was building a trail through to Thompson River which was reported to be the greatest gold field ever discovered in the world. The trail ran west from Whatcom to Ten Mile, and crossed the Nooksack just below where Everson now is. From there was straight to the Chilliwack River, up that river to the divide. A man named LACY or DELACY was responsible for the information that such a route was feasible. He was a sort of a civil engineer, and said it was practicable for a good wagon road and that the grade was easy through to Thompson River. Backed by Henry ROEDER he was supposed to be cutting a preliminary trail. People were arriving daily in the town of Whatcom by the hundreds from all along the coast, California contributing the largest number. Hundreds of useless and unnecessary things were shipped in by the tenderfeet. There were stages, Concord coaches, omnibuses, and horses to stock a stage line from here to Thompson River. As it had been reported and advertised that Whatcom was the only feasible starting place men came prepared to accommodate and others to bunco. Men were camped all along the beach from the mouth of Squalicum Creek nearly to Chuck-a-nut Bay. Their number was variously estimated from 8,000 to 10,000. For debauchery and immorality I don’t believe it was ever equaled on the American continent, if in the world. There were as many Indians as whites and the Indians readily mixed with the whites in their debauches. Many saloons and eating places all selling liquors sprang into existence and Indians were as good customers as whites. The heaviest blow the Siwashes [derogatory term for Indians] of Puget Sound ever had was that gold rush to Whatcom. Debauchery and disease fastened themselves upon the tribe, and from that time until this, the tribe has dwindled until it is nearly extinct. Day by day the crowds in Bellingham grew larger. The trail was not completed, but reports were that it soon would be, consequently none were leaving and the number went on increasing. Myself and two others concluded to try and make it through on foot and wait no longer for the trail. Taking all we could pack on our backs we started out on the trail. We found quite a number had preceded us, and were camped at various places along the route. At Chilliwack River we found the largest encampment, the most of whom declared there was no trail further up the river. I was not to be balked. I was going on until I found the men working on the trail. One of my companions went with me. The other refused to go any further, but agreed to stay where he was and guard our things until he heard from us. We took provisions for two days only. After a very few miles we found no signs of a trail or of any work being done. We did find a sort of blind Indian trail that we followed until we came to the lake from which the river flowed. I could not tell the length or breadth of the lake, but it was quite a body of water with insurmountable cliffs of rocks on all sides. There was no trail nor was there any possibility of making one, and much less of making a wagon road. Not until then did it begin to be clear to me that the great mass of people gathered at Whatcom, as well as myself had been buncoed. After spending one night and part of two days trying to scale the cliffs we gave it up and took the backward trail. When we got to the place where we had left partner and provisions we found we had neither. The Indians told us he had gone on with other gold seekers toward the Fraser river. There was nothing for us to do but go on and get back to Whatcom as quickly as possible or starve to death. I was hungry and tired by the time we reached the Nooksack, but luckily we were able to get some provisions there to last until we got home. We had agreed to say nothing of what we had discovered but the news had preceded us and there was great excitement in camp. At once a great demand existed for boats to go around to the mouth and up the Fraser River. I went to building boats for which I could get my own price. The crowds of gold seekers were greatly angered at the men they held responsible for the exaggerated reports that Whatcom was the only feasible and practical starting place by which to reach the Fraser and Thompson River mining districts and several indignation meetings were held and great resolutions were passed. But, when they come to look for the men they had found responsible they found they had been called by sudden and urgent business to other parts of the country. From Mr. ROEDER’s account to me and others afterwards it seems to me and others afterwards that the engineer had buncoed him out of a large amount of money on the trail proposition and misrepresented everything generally. From the engineer’s representations ROEDER had made his statements, and coming from such a source it was taken as the truth. Thus the first Whatcom boom ended. The men began to disappear. In small boats, in canoes and in steamers -- any way to get away and bound for any place on the Sound or for Oregon they went. Two or three of the steamers carried full loads of pennyless loads back to California. Still a few stayed and made good citizens. Among those I can name are LANCE, late of Lummi Island, ALLEN of Marrietta, Rev. John TENNANT of Lynden.

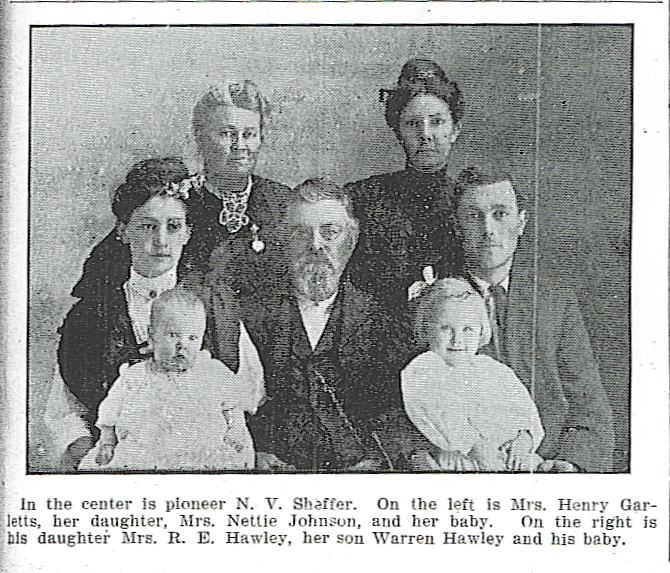

|

From The Lynden Tribune, August 5, 12 and 19, 1909; copied by Susan Nahas

|

Back to Whatcom GenWeb Home Page