|

BRADFORD ROBBINS GRIMES

On the Trail-Gulf to Dakota

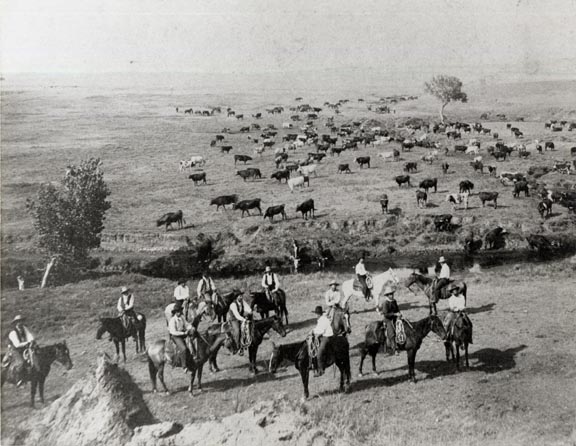

“The WBG ranch kept from eight to

ten men busy branding the year around. The annual roundup began in

early Spring for it was traditional that herds start north not later

than the first week in April. The Chisholm Trail lay about ten miles

distant from the ranch. Let me tell you about a drive I made to

North Dakota.

“One day my father told me I was to

be top man or trail boss in charge of twenty-five hundred head of

cattle he was sending to our ranch in North Dakota, and that he

would pay me twenty-five dollars a month, and grub. Of course, I

felt mighty important as any boy in his early twenties would.

“When we started the round-up thirty

or forty men covered an area fifteen miles wide and rode between the

different creeks, Juanita, Colorado, Caranchua, Tres Palacios and

others. It didn’t take so very long before we had three thousand or

more head milling and bellowing close to the ranch, but it took us

some time to cut out those we were to drive north and brand them

with our trail brand “G.” In addition to the WBG ranch brand they

already carried.

“All cattlemen used a trail brand as

an extra precaution and for quick identification of stock that might

stray, become stolen, or get mixed with other herds on the way.

“We also rounded up a remuda of one

hundred extra horses which were pretty wild. We placed them in

corrals so that they could become acquainted with each other and

lose some of their wild notions before becoming a part of the trail

outfit.”

“A remuda was always placed in

charge of a horse wrangler who accompanied a drive and remained at

the rear of the herd. He was responsible for them. At night he tied

the horse he was riding with a long rope, which he attached to his

arm so that if the main bunch strayed while he was asleep, as it

always did, his horse would start to follow it, pull the rope and

awaken him.

“When the cattle were to be counted,

six men formed a lane through which the animals passed, sometimes

singly, sometimes, two, three, or four at a time. We used peas,

beans, or tied knots in strings to keep tab of the number of head.

When twenty-five hundred had been accounted for we turned the others

loose and headed them for the range.

“When all was in readiness for the

drive to begin, our crew consisted of fourteen riders, Oz, our

colored cook, who was in charge of the four mule chuck wagon, the

horse wrangler, who would not only have to look after the remuda but

rotate remounts for those horses that would become galled or tired

out, and myself. Seventeen men in all.

“Oz was one of our slaves. Where he

got the name of Osborn Williams I never knew until he told me one

day he had “just picked it up.” He was a flat-nosed fellow, a fine

cook, and a happy spirit. I can hear him singing, and I can hear the

tunes he played on his ten cent harmonicas which he always carried

with him.

“My father had furnished me with

money with which to buy foodstuffs to replenish our larder on the

way. Oz always felt very important to when telling me what was

needed. And he was an important member of the crew, for upon him

rested the responsibility for having meals ready to bolster up the

riders who were often tired out from lack of sleep and hard riding,

enervated by the hot dustladen winds that blinded them and the

cattle alike, or wearied by rains that made the trail a quagmire and

the going (trebly) terribly hard.

|

Picture courtesy of Robert M. Davant & Matagorda

County Museum. |

“When we left the ranch we had about

one thousand pounds of food supplies consisting of, in part, green

coffee, which we parched in a dutch oven, several sacks of sugar and

flour, bacon, rice, hominy, beans, and dried fruits. Oz always had

soda biscuits and flapjacks on the menu. Of course, we didn’t have

any printed menus. We just took what Oz gave us and ate it or went

hungry. Eggs were a few and great luxury. Rabbits, prairie chickens,

and antelope could be killed along the way if you were a good shot.

As I’ve said before, I don’t believe I was ever considered a good

marksman. ‘

“The smell of frying, bacon, the

odor of “dried salt,” which was the name we gave pork slabs, and the

aroma of boiling coffee, never failed to whet our appetites. We used

tin cups and tin plates.

“A twenty to thirty gallon barrel

was lashed on either side of the chuck wagon and filled with water

for drinking purposes. As we didn’t have any ice you can readily

understand how warm the water became. A poncho, or dried hide, was

slung under the wagon and filled with kindling. It was the duty of

Oz to replenish the supply of kindling with dried chips picked up

along the way as in many districts wood was priceless, and we had to

use it sparingly. But it was water first, last, all the time for man

and beast alike.

“The crew ate in turns as they

changed shifts, and Oz knew he would be busy from sunup to sundown,

and lots of times the boys would wake him up at night and tell him

they had to have grub.

“Our average move did not exceed

twelve miles per day. We always timed a drive so as to reach a creek

at about noon and another before dark, at which times we would throw

the herd off the trail to graze and water. When the noon stop was

made we left the herd in charge of just a sufficient number of me to

handle it while Oz went on ahead several miles and prepared dinner

for the others. When the men with the cattle reached Oz he was ready

for them and the others would be turned over to the boys who had

already had their dinner and the trek continued. Nightriders took

charge immediately after supper.

“Each rider had a yellow slicker, or

rain coat, two blankets and a tarpaulin which he laid on the ground,

if damp, or used with his blankets when nights were cold. And each

had his favorite horse.

“The trail was about on-fourth mile

wide and deeply rutted by the hoofs of the cattle which were always

wild and hard to handle at the start, but much more docile by the

time we reached Austin, Texas. Unless stampeded, they held the trail

fairly well. Always at the start one animal would take it upon

itself to be the leader of the herd, and no matter how often we

stopped for water and feed that critter would head the bunch again

when we started.

“We left the ranch on afternoon at

about four o’clock. Fifteen hundred miles lay ahead of us. None of

us knew that we would, but we hoped to reach our destination alive.

Dust storms, tornados, Indians, and renegades, were no strangers in

those days. We bedded down the first night we were out, and sunrise

next morning saw us well under way. We timed the day’s drive so as

to reach the Navidad River before sundown. We reached

it that evening, threw the herd off the trail and bedded down for

the night. In due time we passed close to Lockhart, Texas, and while

the herd continued its way, Oz and I bought about one hundred

dollars worth of supplies. Lockhart was then a nondescript

settlement of a few hundred people.”

“We reached Austin, Texas, about one hundred and

fifty miles from the ranch without anything special happening. I

paid of and turned back six riders as the cattle were giving little

trouble. Some of the boys who received part pay bought overalls or

shirts, or other wearing apparel, while others visited the saloons

and returned to outfit in a more-or-less worse for wear condition

but still quite able to sit in their saddles and nurse the herd. We

remained in Austin thirty-six hours during which time additional

foodstuffs were bought. The city then had a population of between

twenty and twenty-five thousand people.”

“Leaving Austin, we passed close to

Temple, Texas, without stopping, and when we reached Fort Worth,

about four hundred miles from home, we rested the stock and

purchased enough grub to carry us through to Dodge, Kansas.”

“When we crossed the Red River at Doan’s Ferry, so-called after a man by that name who operated the

ferry, we found ourselves in what was spoken of in those days as The

Beautiful Indian Territory.”

“Quanah Parker, a half-breed, was

head of the Comanche tribe. Quanah was waiting for us when we

stepped onto his land. I knew what was expected of me and did not

hesitate to hand him fifteen good dollars as a pourboire for good

will, which would permit me to feed and water the herd without being

molested as we passed through the Territory. He was most polite,

spoke excellent English, and when thanking me he assured me we would

not be harassed by his tribesmen. I have always believed he must

have had scouts out who promptly reported to him when a herd would

reach the river. He always met them on the north bank and collected

tribute.”

“When Indians asked cattlemen for an

animal they asked in wohaw, a word they had picked up from the

bullwhacker’s call to their long string of oxen freighting to

different army posts. “ Gee” turned the lead oxen to the right,

“Wohaw” swung them to the left. It was therefore easy for the

Indians to connect “wohaw” with beef, or cattle.”

“A few days after I had settled with

Quanah we were bedding down for the night at Cache Creek when

several Comanches rode up and demanded wohaw. Their spokesman was a

little yellow-faced half-breed and as evil looking as you can

imagine. I didn’t appreciate the demand for I felt I had already

settled with Quanah and that should be all that could be expected. I

told the Indian I had nothing to give him. He didn’t seem to care

what I said, and when I finally told him I had made peace with his

chief it had no effect. His demands became more insistent and I

became equally stubborn. In the end, he evidently thought he could

win me over by being more polite. He began to palaver and addressing

me we with the customary Indian salutation, said: “You heap good

chief.” “You good Texan.”

“I emphatically denied the

compliment. I thought I might scare him by letting him think I was

the worst bad hombre ever turned loose on the cattle trail, and

would stand no nonsense. But he wasn’t taken aback. He continued to

tell me what a heap good chief I was until I decided to get rid of

him by riding to the rear of the herd. But when he rode alongside me

I wondered what the outcome of the interview would be. I bandied

words with him as we rode. Before we reached the tail end of the

herd one of my riders overtook us and told me the other Indians were

talking about cutting the herd. I immediately rode back to find the

Indians bunched together and holding a pow wow.”

“It wasn’t long before the Indians

demanded, in one voice, “wohaw” and looked at me in such a way that

I felt cold chills running up and down my spine. Because of my

inexperience I determined to take a chance, I again refused the

demands. Had I been wise I would have given them a steer and they

would have been satisfied, while my refusal to do so might have as I

afterwards realized resulted in having the herd stampeded. Ringed by

my riders, who had their revolvers ready to shoot, we talked and

argued until I finally told them that if they caused me any trouble

they would have to make peace with Quanah. Whether or not Quanah

would or would not do anything, I didn’t know, but having taken a

stand I was determined to maintain it. What effect Quanah’s name had

on them, I don’t know to this day. Anyway, they finally decided to

leave. I returned to camp and laid down.”

“I became conscious during the night

that some one was moving close by. Opening my eyes I saw that evil

looking spokesman creeping up to my horse. Reaching it, he drew my

revolver from the saddle moral, a receptacle for odds and ends,

where I had foolishly left it. I could see him twisting the barrel

around to see if its chambers were loaded, and they were. I thought,

for sure my last hour had come. I sat up. My movement caused him to

look my way.”

“You good chief, me good chief, he

remarked, meaningly, and his ugly look emphasized his words.”

“I made no reply, and when my

silence must have nettled him he continued to assure me in lurid

language that I was a good chief.”

“You shoot me die, Me shoot, Me die.

All same you die,” he bluntly informed me, and I jumped to the

conclusion that he thought I had another gun. I didn’t tell him I

didn’t have one.

|