|

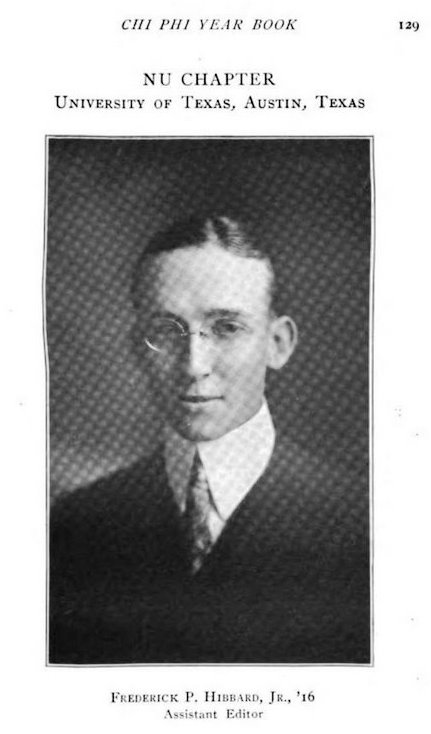

Frederick P. Hibbard Jr.

University of Texas Frederick P.

Hibbard was

born in Denison in the 1890s, but he left

town for good at an early age.

He spent his entire career in the service of his

country, and his job took him

to many foreign lands. He was written about in Time

magazine, and his voice was

heard on radio around the world. Yes, I could be

speaking of Dwight Eisenhower.

But those first three sentences also describe

Frederick Pomeroy Hibbard, Jr. Born in Denison on July 25, 1894 to Frederick Pomeroy and Daisy Bacon Hibbard, Frederick P. Hibbard Jr. attended Culver Military Academy in Indiana, took his A. B. from the University of Texas, graduating in 1917, and did a year of postgraduate work at Harvard. While attending UT, Fred served as Assistant Editor of his fraternity's yearbook and as a Senior was elected editory of UT's monthly student publication, "The Magazine." The fraternity of his choice has the mission of "To build better men through lifelong friendships, leadership opportunities, and character development." (Source : Chi Phi Fraternity) He served in

the army from 1917 to 1919 before entering the

U. S.

Foreign Service in 1920. His appointments

included posts in Warsaw (1921), London (1924),

Mexico City (1926), La Paz, Prague, Bucharest,

and Monrovia. Frederick

was still in the Foreign Service when he died of

an unknown illness in

1943. He was 49. His father died in 1903 at age

39 (when Fred Jr. was 9 years

old). Fred Sr. is buried in Fairview Cemetery in

Denison. You may

know something about the Hibbards, who were in

the drug and grocery business in

early Denison. You may even be familiar

The

second item is an 1805 book once owned by

Hibbard. It is now available for

$3,000, with his name still on the bookplate.

You can read about it and see a

picture of it at The

last item is an audio clip that includes Hibbard

speaking. It's from the Czech

Radio archives, and the occasion was the 200th

anniversary in 1932 of the birth

of George Washington. The complete recording is

just over five minutes long.

The first four minutes are http://www.radio.cz/en/article/97059

In the only foreign

capital named after a U. S. President—Monrovia

of Liberia— Frederick Pomeroy Hibbard, a white

Texan who for 15 For several reasons a

bad diplomatic situation in Liberia is

usually much worse than a bad situation

anywhere else: 1) Political respect for

12,000,000 U. S. Negroes requires that the

post of U. S. Minister to Liberia

shall be held by a Negro, and having a Negro

Minister, though stoutly

backstopped by a white legation Secretary,

does not simplify the art of

diplomacy. 2) When the Secretary of State

wants to send an emissary to Liberia,

he is lucky if there is a ship sailing for the

African West Coast within a

month, luckier still if the emissary reaches

Monrovia in less than another

month. 3) When the emissary lands in a surf

boat at Liberia's harborless

capital, he finds a dirty, ramshackle tropical

town whose inhabitants consist

of about 100 whites, 10,000 blacks, and

1,000,000 rats, where a one-year tour

of duty is considered the equivalent of three

years at Warsaw or Moscow. 4) The

emissary's job is to deal with a Government

controlled by perhaps 20,000 purse-

proud Afro-Americans (who comprise most of the

"landholders of Negro

blood," the only qualified voters according to

the Liberian Constitution)

who for the last century have never succeeded

in controlling the million or

more Afro-Africans who inhabit Liberia's

43,000 square miles of equatorial

jungle. 5) If everything does not go well in

Liberia, it is just too bad for

the U. S. State Department which is held

responsible by the world at large. For

Liberia was founded over a century ago as a

colony for freed Negro slaves from

the U. S., has a Government with a President,

a Senate, a House of

Representatives and all other U. S. fixings.

U. S. honor cannot afford to let

the British from Sierra Leone or the French

from the Ivory Coast step in and

clean up. During the last five

years conditions in Liberia have been salt in

the wounds of the State Department. The

British objected that the rats in Monrovia

were so bad that bubonic plague was prevented

from spreading through West

Africa only by the fact that it had no harbor

in which ships could dock; that a

smallpox epidemic ravaged the interior; that

the simplest health measures were

unknown and Liberia More serious was the

charge that Liberian President Charles Dunbar

Burgess King, along with his Vice President

and several Cabinet members, had

been profiting by having their "Frontier

Guard'' raid villages of their

Afro-African countrymen, torture women and

chiefs, seize black bucks and sell

them into slavery in French Gabun and Spanish

Fernando Po. When a League of

Nations Commission verified the practice.

President King and his followers, on

stern advice from Washington, resigned. Next

Liberia, under President Edwin

Barclay, defaulted on its loan of $2,250,000

from Harvey Firestone. In 1925

when rubber was $1 per Ib. the State

Department had encouraged Mr. Firestone to

start a huge rubber plantation in Liberia and

lend the African Republic money

to pay off its European and other debts. Mr.

Firestone planted 55,000 acres of

rubber trees, built 100 miles of road (five

times as much as Liberia had ever

had before), hired thousands of natives at 25¢

a week, gave Liberia a brief

boom. Then with Depression the Liberian

Congress seized the revenues set aside

to service the Firestone debt. The U. S.

protested that this was contrary to

the Liberian Constitution. Proclamations were

posted that any Liberian Supreme

Court Justice who held the Act

unconstitutional would be assassinated. Since the U. S. could

not stop these occurrences, the League of

Nations tried. Liberia is a charter member of

the League, for it had joined the

Allies one day during the War when a British

warship anchored off Monrovia. The

League found that Liberia, besides having no

health service, had no budget, no

accounts, no money, that its trouble was, as

Lord Cecil put it, "the

incompetence of the Government and

corruption—but rather more incompetence than

corruption." The League offered to send

Liberia a Government adviser to

set things right. President Barclay proudly

declined. The League threatened to

expel Liberia, then looked up its own

constitution, found it had no authority

to do so. Last September U. S.

Diplomat Hibbard took one of the least

pleasant assignments in a career which had

taken him from Poland to Peru. Only

difficulty he was spared was the presence of a

U. S. Minister at Monrovia.

Charles E. Mitchell, the last to hold that

post, had been retired because of

the prolonged lack of recognition of Liberia.

As Charge d'Affaires. Mr. Hibbard

had spent long days in polite palaver President Barclay,

sitting in his wicker rocking chair on the

second-story veranda of the Executive Mansion

where he daily looks down on the

tall grass and tin cans in the square below,

graciously accepted the offer. Mr.

Hibbard privately thanked God that his job was

done, hoped he would be

relieved. In the U. S. hundreds of Negroes

began to besiege Postmaster General

Farley's lieutenants with requests to be

appointed U. S. Minister Resident

& Consul General to Liberia —at $10,000

per year. The State Department was

so happily excited over this settlement of

"the Liberian crisis"

that, in the mimeographed announcement of its

accomplishment, it carelessly

called the President of a friendly nation

Edward instead of Edwin. http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,754906-3,00.html#ixzz0m4yKbHeh

January 17, 2016  Biography Index Susan Hawkins ©2025 If you find any of Grayson County TXGenWeb links inoperable, please send me a message. |