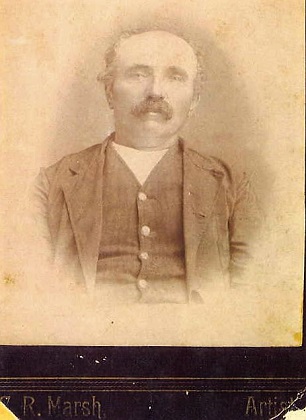

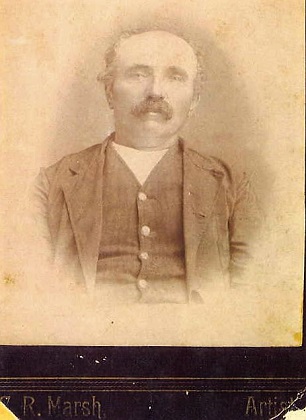

Albert Regnier

The Daily Hesperian

(Gainesville, Texas)

Friday, July 22,

1892

pg. 3

"It's You, I'll

Kill You."

She Begged

Piteously for Her Life on Bended Knees

Sherman, Tex.,

July 20 - Albin Regnier this afternoon shot

and almost

instantly killed his pretty granddaughter,

Josephine Gremeau, at his home, No. 758

S. Montgomery street.

There is a

pathetic story leading up to this terrible

domestic tragedy. A few days since,

Ben Simpson, a stepson of Regnier, imparted

to him a secret concerning the girl.

This the girl had herself told to Simpson

some months since, but at her urgent

request he has kept her secret because she said if her

grandfather found it out, he would kill her

as he had threatened to do if she ever went

astray. Simpson said he

had pleaded with her to break off her

acquaintance with the young man who had

caused her ruin or force him to give her his

name.

To the latter

step she objected, but after a while she

consented, saying that she would do

so only to save her life, as she knew she

would be killed if the matter ever reached her

grandfather's ears.

Simpson himself

carried a letter to the young man, which

subsequently proved to be an

appear from her for the protection of a

name, though Simpson at the

time did not know what it was. Matters grew more

and more complicated and more and more was

leaking out about the misfortune of the poor

girl and Simpson, finding that he himself was

having the finger of suspicion pointed at

him, decided to tell the whole matter

to Regnier just as it was.

This afternoon

Regnier and his wife, who were at home

alone, began to discuss the

matter and a hot and stormy interview

followed. Miss Lillian Morton,

who was standing just across the street,

says Mrs. Regnier told her husband

something and he replied: "Why didn't you

tell me that before?"

Mrs. Regnier gave

a woman's reason, "because," and Regnier

replied:

"It's a lie," and

his wife rejoined: "Well, I'll prove

it."

She then went to

her daughter's, Mrs. E.W. Haskell, who lives

at No. 840 on the same

street about a block away. Mrs.

Haskell says that her mother told her that

Regnier was laying the whole blame upon her

(Mrs. Regnier) and her children,

Mrs. Haskell and Ben Simpson, saying they

were the cause of her grandfather's trouble

and disgrace. This Mrs. Regnier

had strenuously denied and then went over to

the house to sustain their mother in what she

had said. When they got there Regnier

was

gone and Mrs. Haskell remained at the house

with her mother. They sat talking of

the matter for probably half an hour, when

Miss Josephine Gremeau and Miss

Frances Gremeau came back from up town. They said they

had met Mr. Regnier up town at the court

plaza and that he said something

to them as they passed him, but that they

could not understand what it was. Hardly

had they time to take off their hats when Regnier came up

to the door leading to the dining hall and,

addressing his granddaughter, said: "It's you; I'll

kill you."

The poor girl in

a tone of pleading supplication , as

her grandfather drew a pistol from where

it had been concealed in his pants band,

cried out: "Oh, grandpa, don't, please don't."

Mrs. Regnier

rushed forward and piteously begged her

husband to kill her, but not to

kill the poor child. Rudely was she

shoved aside and deliberately

leveled the pistol at the girl who had

refused to run out of the house as told

to. She was kneeling before her

grandfather praying in agonizing

tones for her life. Regnier fired 3

times and as his daughter, Francis, fled

down the street he called to her

to stop, that he intended to kill her.

After

the shooting Regnier deliberately walked up

to the city and surrendered to Deputy Sheriff

Gene Andrews, to whom he very coolly said:

"My granddaughter

has disgraced the family and I have killed

her, or at least I have tried to."

In fact, so

calmly was this said that the office, while

he took him in charge, half doubted what

he said. He had no pistol at this time.

While several have been

found from whom Regnier tried to

borrow a pistol, where he got it is yet

unknown. At the jail he refused to

talk to the reporter and simply said: "I have nothing

to say. What I told the officers they

can tell you."

James Clark, who

lives near, was one of the first to reach

the house, and when he got

to the prostrate girl she was gasping out

her last breath. She recognized

him and faintly said: "I have been

shot. Oh, what shall I do?"

She did not live

exceeding 2 minutes from the time of the

shooting. Mrs. Regnier is

crazed, wringing her hands and crying

piteously. She has not been able to

make a statement of the affair at all.

Denton County

News

Wednesday, July 27, 1893

pg. 1

KILLED HIS GRAND DAUGHTER

Because She had Disgraced Herself

Sherman, Tex., July 20 - Albert Regnier, a

man of French extraction,

about 6 o'clock this evening killed his

grand-daughter, Josephine

Greamean, [sic] aged 17 years. Regnier was

heard to abuse the girl on

the streets this afternoon and

after he was arrested told the officers that

the girl had

disgraced the family and he would rather be

in prison than be disgraced.

He got a pistol at Lindsey's second hand

store this afternoon, as he

claimed, to kill a dog. He went home

and commenced his bloody

work on the poor girl, who is believed to

always have been pure and

virtuous. The first shot missed her

and she fell on her knees

begging for mercy, but another ball pierced

her heart and still another

entered her breast. There

is much excitement in the

city, come believing he must be

insane. Others who know the man

say he is perfectly sane, but mean.

LATER - - - An examination was held

over the remains of

Josephine Greman [sic], who was so cruelly

murdered last evening by her

grandfather, Albert Regnier, and the alleged

disgrace upon the family

had no foundation. The deceased has

been exonerated. Either

the grand-parent was misled in his belief

concerning her or there must

have been some other motive leading up to

the affair.

The Galveston

Daily News

Friday, July 22, 1892

pg. 5

THE SHERMAN TRAGEDY

The Fair Victim Buried - The Coroner's

Inquest

Sherman, Tex., July 21 - The body of

Josephine Gremeau, the girl

murdered by her grandfather, Albin Regnier,

was laid away at the

west side cemetery this afternoon, and there

was scarcely a dry

eye in all the concourse when Rev.

Mountcastle, the Methodist clergyman

who officiated at the burial, consigned her

body back to the dust of

earth.

The inquest has been finished, as far as the

evidence is

concerned. At the request of Coroner

Huikle of the First precinct

a postmortem examination was made upon the

body. This was to

demonstrate to a certainty whether or not

there was truth in the

broadcast rumor that the unfortunate young

lady was in a delicate

condition. The examination set at

naught all such reports.

Dr. Lankford in his deposition said:

"I found nothing to indicate

that the deceased was other than a pure and

virtuous girl."

Regnier still maintains his silence. He had

a conversation with his son

Joe, a lad of 18, to-day. To all

others he has the

same reply: "I don't care to talk of

the matter." Last

night, however, he said to Deputy Sheriff

Gene Andrews: "I made her

kneel at my feet and told her for that I

intended to kill her, and she

asked me to shoot." This is quite at

variance with the statement

of Mrs. Haskell, an eye-witness, who before

the coroner to-day, said,

as she said last night to the News

reporter, that the girl was pleading

for mercy when she was killed.

The Galveston

Daily News

Sunday, July 24, 1892

pg. 7

PROUD HOUSE OF REGNIER

The Prisoner's Statement to the News

Reporter

His Heart Made Glad by the Proven Innocence

of His Daughter - How He Received the News

Sherman, Tex., July 22 - Ben Simpson, whose

name appeared quite often

in connection with the Regnier-Gremeau

homicide, was under

detention for a short while. Constable

Whitesides, who had him in

charge, stated to The News reporter that

Assistant State's Attorney Jamison did not

believe he could in any way be implicated,

and hence he released him.

To The

News reporter and Chief of Police

Melton, Ben Simpson said:

"I don't know that any one ever suspected

that I was any ways connected

with the girl's errors, if she had been

guilty of any and upon this I

alone have her word, but there was no doubt

that Regnier thought I and

my mother and sisters were rather against

the girl and trying to

condemn her."

"Is there any truth in the report that Miss

Josephine repulsed an offer of marriage from

you?"

"None in the least and a package of letters

received by me from her and

which I afterward returned to her, if they

could be found, would

completely knock that story out."

In a more extended interview the young man

went into details of his

version of the dead girl's history, always

giving her statements to him

direct for authority. Among other

things he said:

"I did not tell Mr. Regnier that Miss Josie

was in a delicate

condition, and she never told me that she

was. It was of the

error that she had told me of 2 or 3

months before that I told

him at her request. Rumor alone seems

to have made the holding of

a postmortem examination seem necessary.

"You made one error or perhaps oversight in

quoting my statement.

I did not go to Mr. Regnier [sic] with a

statement of Josephine's faults

of my own account solely, but on the

preceding evening she had

requested me to do so. When I did tell

him he did not seem to

manifest any great anger, but simply said:

"'You did right, for I am

the proper person to be told of it."

There was also a slight error in the account

yesterday, which said Mr.

Regnier and Mrs. Simpson were married in Van

Alstyne. Mrs.

Simpson had been living in Sherman oft and

on for some time when she

met Mr. Regnier. They were united in

marriage at the residence of

John Stanley in east Sherman on N. Newton,

between Pacific and the

Texas and Pacific railway. Both of

them had, however, been

residents of Van Alstyne and vicinity."

When Constables Blair and Whiteside went to

the jail yesterday evening

they told Regnier the result of the

postmortem examination and that

the physicians had pronounced the rumors

as false. The old

man appeared stunned for a moment and then

exclaimed:

"Oh, my God, and ------- lied to me."

To-day a News representative with Drs.

Michael and Saddler visited the

prisoner. When called, Regnier

greeted each of his 3

visitors by name. Dr. Saddler inquired

how he felt, to which he

replied: "I feel as well as a man could

under the circumstances, but I

feel so much more relieved than I did

yesterday before Mr. Blair came

up and told me that my poor child was

innocent of the guilt they

charged her with.

"Was it upon the statement of ------- that

you shot your granddaughter?" inquired the

reporter.

"Yes, upon ------'s statement, backed up and

substantiated by ------ and ----."

"What did ------ tell you of the case?"

"He said that Josephine had gone wrong

months before and had succeeded

in destroying the evidence of her shame, but

that misfortune had again

overtaken her. He said he did not

desire that any blame might

rest on him and that he had told the

straight of it. I gathered

from what he said that some of this

information had come through

------. I was frenzied and my

brain was burning up with

shame. I gave the reports the lie, but

they backed themselves up

with corroborating statements and with

letters giving me the name of

the young man who was charged with the ruin

of my poor girl.

"I came up town and got the pistol.

No, I won't tell you who gave

it to me. It was a Colt's 5-shooter 45

caliber. When I got

back I said to Josephine:

"'If you are guilty, I am going to kill

you,' and as she sat in front

of me and said: 'Papa, I believe I am," I

fired. Only one shot

was intentional, the other 2 were accidental

and involuntary.

They say that I called out to my little girl

Frances that I wanted to

kill her. I called to her that she

ought to come and look after

Josephine and she ran of crying: 'Papa, I

can't do it.'"

"If Josephine had tried to run I would not

have followed her, but when

she stood firm and never denied her guilt I

killed her. Of

course, I killed her. I would have slain 50

of my children rather than

that one of my name should live to walk

about to be the subject of

remark and reproach. They say that

they pleaded with me for her

life. They stood there prepared to condemn

her as they had already done

and point the finger of shame at her.

I might have killed more of

them, but there are some people too

miserable to died for honor's

sake; better that they should die with the

curse of guilt upon their

consciences dragging them down slowly,

pitilessly.

"The doctors have made my heart glad because

they have assured me that

my poor dead child had not dishonored the

name that has been a proud

one always.

Here Regnier, overcome by his feelings,

stopped a moment and wiped the tears from

his eyes. He resumed:

"The family of Regnier has always for 20

generations and more been one

which carried with it respect and was a

guarantee of honor and

chastity. King Humbert of Italy has

for his second name Regnier

and directly can his right to bear it be

traced back to my own

family. More than 100 years ago a

daughter of the house of

Regnier fell and her father, a colonel in

the army of Napoleon,

traveled for hundreds of miles to kill

her. His purpose was

discovered and she was hidden away from him,

but he found her and she

died by his hand.

"She was the first one of all our women to

fall, and when they told me

that my child had gone astray I determined

if it were true to place her

beyond the reach of those who would scorn

her and point to her with the

finger of shame.

"I have given instructions that my wife be

given what is her property

and the doors of the house be nailed up. I

want Frances to go live with

her aunt, Mrs. Stanley, in east

Sherman. I am glad you tell

me she is at Mr. Clark's house. He is

a gentleman and has a kind,

fatherly heart. Josie!

My God, to think that she did not deny

it. She must

certainly have not understood fully the

grave nature of the charges

they had against her.

To the reporter, as the visitors were

leaving, he said:

"Tell the people in your paper for God's

sake, for the sake of honor, to suspend

judgment until the story is told."

The preliminary trial had been set for 10

a.m., but it was postponed

until 2 p.m. when it was called in the

district court room, the regular

justice court room being to [sic] small to

accommodate the great crowd

of spectators, who began to flock in as soon

as the officers were seen

coming across the court plaza with their

prisoner. The prisoner,

after glancing around the court room once,

never removed his eyes from

a legal paper he held in his hands until his

daughter came in and

throwing her arms about his neck began to

weep. The prisoner then

gave way to his feelings and cried.

Then the legal machinery began to move, the

witnesses were collectively

sworn, and Miss Lillian Norton placed on the

stand. Taking testimony

was necessarily slow, as it had to be taken

verbatim. Her

testimony was in substance what has already

appeared in print as

her statement.

The testimony of James Clark and Mrs.

Haskell did not materially differ

in any essential point from what they have

heretofore told The News

reporter.

After their testimony was heard, court

adjourned until 8:30 in the morning.

The Galveston

Daily News

Monday, July 25, 1892

pg. 6

The Horror at Sherman

Regnier's State of Mind Before the Homicide

Testimony of Ben Simpson, the Informant,

Bearing on a Quarrel with Deceased Previous

to the Fatal Day

Sherman, Tex., July 23 - The case of the

state of Texas vs. Albin

Regnier, charged with the murder of his

pretty grand-daughter Joseph

Gremeau, has thrown everything into the

background with the public

to-day. When the case was called

in the courtroom this

morning there were several spectators

and gradually the crowd

gathered in numbers. There was much

excitement if not more than

yesterday. The defendant's counsel was

this morning reinforced by

Capt. J.D. Woods.

At 8:30 o'clock the prisoner began to write

and for over an hour

he wrote steadily. Then he folded up

the paper and gazing

intently at the pile of books on the

desk before him maintained

the same immovable countenance of yesterday.

Miss Frances Regnier was the first witness

placed on the stand. As to

the actual killing she knew very little, not

being an eye

witness. She said in substance that

for several days before the

homicide her father had acted peculiarly. He

did not talk much but

would pace back and forth in the yards. She

was not close enough to him

at such times to tell whether or not he was

talking to himself.

He would answer short, but not harshly, when

spoken to and when he did

talk it appeared to witness that his mind

was clear off of what he was

talking about.

She did not remember whether her father had

spoken to her stepmother or

not. When she and Josephine got home

from up town on the

afternoon of the homicide the witness said

there was something so

strange about the house that she felt like

someone was dead, and she

asked them what had happened. She

could not exactly explain it,

but she felt just like something was going

to take place. When

she heard some one say that her father was

coming, she went to the east

front door. She heard some one say

something in the middle

room. She could not tell who or what

it was, but the fear if

impending danger still remained with her.

Josephine had gone into the

middle room only a few minutes before.

She did not know the details of the killing,

which occurred soon after

this. She didn't know of any serious

trouble that had occurred in

the family since the death of her

half-sister that would have caused

such depression. When her mother died,

of course, her father was

sad. She didn't know that he acted

differently from what any

other man would have acted under the same

circumstances. The

witness also detailed how her father had

acted when the other little

troubles had taken place. He seemed to

be sad and troubled, but

he didn't act strange. She did not

remember the first time she

noticed him acting strange - whether it was

Sunday, Monday or

Tuesday. He had a strange look in his

eyes. Don't remember

the hour of the day. Didn't notice his

walking about in any particular

place in the yard. The neighbors saw him

walking about strangely.

During the time she never noticed him

talking to Mrs. Haskell or her

brother Joe. He (Regnier) spoke to

witness pleasantly the

afternoon before the homicide. Never

heard him say he would kill

any of the children who disgraced the

family. Had always treated

witness and Josephine kindly.

Some time was consumed in reading over the

deposition of the witness, which she signed

after the usual few corrections.

Deputy Sheriff Gene Andrews was the next

witness placed on the stand. In

substance his evidence was as The News

has heretofore published. He had known

the defendant for a number of years; he had

surrendered to

witness and told him what he had done; that

he had done it on purpose;

said he had returned the pistol to the man

from whom he had borrowed

it. He noticed that there was something

strange in his expression when

he gave up.

Dick Walsh was the next witness. He

has known the defendant for

some time, probably 6 months. Witness

kept guns and pistols; saw

defendant the afternoon of the shooting; he

was at the store; he wanted

a pistol; let him have it; it was a

45-caliber; he put it in under the

waistband of his pants and held it there

with his hands. He then

went southward out of the store. He

said he wanted to kill some dogs. He

borrowed the pistol from witness. He

did not speak of buying a

pistol. He appeared to be quiet

and was sitting in a chair

when witness came in. Witness sat down

by him and talked.

He appeared to be all right. He

was first told that the

pistols were all new and not to be loaned

out. It was then that

he told what he wanted with the

pistol. Witness asked him why he

didn't get a shotgun and he (Regnier) said

they would see the

shotgun. Witness told him he was

liable to shoot at a dog and to

kill somebody on the other side of town with

the pistol, and he said,

"No, I'll hit 'em." Witness finally

loaned an old "45" which was

in the drawer; said he wanted it until

morning; said dogs would come right up to

the foot of his

bed. The pistol was returned;

don't know by whom except by

hearsay; saw it again in probably 30

minutes, examined the pistol and 3

shots had been fired. Two cartridge

had been skipped and the 4th

one fired. There might have been

clerks present at witness' store

when Mr. Regnier went to borrow the pistol;

no one else took part in

the conversation.

Here the prisoner handed his counsel the

paper he had written during the morning.

The next witness placed on the stand was

C.W. Moore, an employee of Mr.

Walsh. In substance his

statement was that on Wednesday

last he saw the defendant; had known him for

8 or 10 years; knew the

vicinity of his home on S. Montgomery

street. It is about 1/2 of

a mile. He was looking at pistols at

the store. He didn't

say he wanted to buy the pistol then.

Said something about it not

suiting him to pay the money out just at

that time. Witness told

him he could rent a pistol at George

Lindsay's. He went out and

was gone some little time, when he came back

and said that Mr. Lindsay

was out of everything of that kind.

Regnier saw Mr. Walsh about

this time and went to him.

After Mr. Walsh had finished talking to

another gentleman who was in

the house at the time he (Walsh) turned his

attention to the

defendant. He had said something

to witness about dogs

bothering him. Did not notice anything

unusual in his manner at the

time. Saw him not longer than 30

minutes after he left the

store. He came in at the front north

door then. Had his

right hand down in the waistband of his

pants. He pulled out a

revolver and handed it to witness saying, "I

am through with it."

He said nothing further, but walked out and

went up the street.

Witness examined the pistol. It had

evidently been recently fired 3

times. Witness put it in the drawer

and afterward told Mr. Walsh

it had been returned. Described the

condition of the emptied

hulls about the same as Mr. Walsh. He

seemed to be moderately

cool and collected, but appeared to have

just walked rapidly. The

pistol was a single action 45-caliber Colt.

At the conclusion of this testimony the

state announced that it was not

probable that they would desire to introduce

anymore testimony and

rested. Court then adjourned until 2 p.m.

Regnier was brought into the courtroom a

little before 2 o'clock this

afternoon. He said to The News

reporter: "Your report of my statement of

the affair was verbatim and

correct. It was just as it all

occurred."

At each opening and closing of a session of

the court Regnier's little

daughter affectionately kisses her father

and the old man shows plainly

the deep emotion under the influence of

which he is laboring.

The first witness placed on the stand this

afternoon by the defense was

Ben Simpson, who said in substance: "My name

is Ben Simpson. I am

a step son of the defendant. I was

living at 849 S. Montgomery

street the day of the killing. That

had been my home for about 10

years. I was living with my

mother; that was her

property. I have not been living with

my mother all the

time. My mother has not made it

her home for about 4 or 5

years since she married. Since then I

have lived with my sister,

Mrs. Haskell, and her husband, that is when

I was there. No, 849

S. Montgomery street has been occupied by

Mr. and Mrs. Haskell since my

mother left. That is not far from Mr.

Regnier's house.

"I have known the defendant between 4 and 5

years. I did

not know him before he married my

mother. I have not been with

him much and have not had as good

opportunities to get acquainted with

him as others have had. I have seen

him with his family very

frequently. He always treated them all

right when I was about

them. I never saw him treat any of

them harshly. He treated

Josephine like he did the rest of the

family. He seemed from his

actions to love her as he did his own

children. I never heard him speak

a harsh word to her.

"He never in any conversation with me

indicated that he had peculiar

ideas about female virtue. He never

said that he would rather see

one of his children dead than go

astray. I talked with him about

Josephine the day before the killing.

It was between 12 and 1

o'clock on Monday between his house and

town. We were coming to t

own, I overtook him. I told him I

wished to tell him something

concerning Josie that was secret. "I

told him that she had been

gotten away with by one man in town and one

man out of town and all

that I knew she had told me herself.

I didn't tell him the

particulars. I told him I

thought he was the one to know

it. He replied, 'That's right; go

on.' He turned around and

said, 'I'll go back home.' He went

toward his home. I came

on to town. He didn't seem

affected in any way by what I

told him. He didn't seem

shocked. He walked a few steps

after I told him before he started

back. I never looked back to

see if he went home.

"I never had any other conversation with him

in reference to

Josephine. I didn't tell him the names

of the parties who had

wronged Josephine. I did not tell him

when or how it was. I

saw him in about a half hour in town.

He was walking up the

street by himself. I did not speak to

him. I saw him next

that night at home. He was sitting in front

of the house. I

did not speak to him. I was at his

house that night. I

heard him talking with no one that night

except my mother. I paid

no attention to the conversation. I

didn't usually pay any

attention to their conversation.

"We were all together. I was talking

to the girls and my

mother. Josephine and Francis were the

girls. I talked to

them both in and out of his presence that

night. I don't

recollect the conversation, but it was first

one thing and

another. Before night I told Josephine

of what I had told her

grandfather. I don't know where Mr.

Regnier was. I did not

tell Josephine that night. If

Mr. Regnier had anything to

say to the girls that night I did not hear

him. He did not join

in our conversation at all.

"I never observed him closely that

night. I did not notice how

the information was affecting him. It

was none of my business how

it affected him. I had only told him

by her request. She

wanted me to tell it to him because I knew

it and she had put

confidence in me. Josephine and I were

on intimate terms. I

first saw the defendant on the day of the

killing, some time in the

morning about 7 o'clock. He was at his

house. He was

walking around the yard. He was

walking around and whittling, as

he usually did when he was walking

around. I merely observed him

as I passed by.

I don't know that it was his usual custom to

walk around and whittle.

"I stayed Tuesday night at defendant's

house. That was what made

me notice him the next morning. I saw

him before I had eaten

breakfast. I did not know whether they

had eaten breakfast at Mr.

Regnier's or not. I went back to

Mrs. Haskell's to

eat. After eating

breakfast I stayed about the place

awhile and then went to town. I did

not speak to Mr. Regnier at

all Wednesday morning. He neither

spoke to me nor paid any

attention to me. He did not ask me to

stay and eat

breakfast. He never did ask me

to stay.

"I saw him next in the afternoon at home

about the middle of the

afternoon. I did not talk with him

then. He, as usual, was

sitting around the door step. He was

alone. He was not

whittling at that time. He was not

reading. I don't recollect

that he even looked up; he had his head

down. I was going to

town. I remained up town nearly all

the rest of the

afternoon. I saw him that

afternoon as I was returning

home. He was at his home. He was

in the back of the lot

them. He was milking or attending to

the cow. That was

about sundown. I was going home.

My sister and her children

were there when I got there. "I know

that I am not mistaken about

it being about sundown, because I can tell

daylight from

dark. I remained at home and ate

supper after

sundown. No one came there after

supper. My sister did not

leave after supper, or if she did I never

knew it. I saw my

mother at her home that evening. When

I went back there after

supper no one went with me. Along in

the afternoon I went up to

defendant's house. I don't remember of

having seen him. My

mother and the 2 girls were

there. Mrs. Haskell was not

there."

Here the witness said that he thought he had

been talking about

Tuesday, but the questions had been asked

him by the defendant's

counsel about what had occurred the day

after the shooting.

"I saw the defendant at his home on the

morning of the day of the

shooting. He was walking a bout in the

yard

whittling. I saw him again in

the afternoon at his home

about 4 o'clock. He was sitting in the

yard in a

chair. I did not speak to

him. He looked up. No

one was with him. My mother was in the

house at the time.

After that I did not see the defendant any

more. When I got to my sister's

she was there with her

children. I remained there until my

mother came to the

house. She came about 20 minutes

after I got to my

sister's. My mother remained about 2

and a half minutes.

She went home and my sister and I went back

with my mother. We

were going to defendant's house. We

were going there to see

defendant and correct some tales that were

told about Josephine.

Defendant was not there when we got

there. No one was

there. I walked through the room and

then went home. I went

back there once again before the shooting to

see if the girls or the

old man had come back. I wanted

to straighten to the old

man the tale I had told him and which he

disputed. He was

not there when I went there the last

time. The girls were not

there.

"My sister went to see defendant for the

same purpose; that was to

prove that the tales about Josie were

true. I would have proved

them by the girl herself. I did not go

back any more until after

the shooting. My business is a

street-walker. I have

no trade at all. While I was not

engaged in going back and forth

to prove up the tales on Josie I was

just loafing around the

streets. I tried to borrow a gun

from Mr. Lawrence and I

tried to borrow a pistol from Mrs.

Gill. I had no short words

with the defendant when I told him about

Josie and I did not

contemplate any trouble with him.

"I did say to Jim Clark before I told Mr.

Regnier of Josie's trouble

that the girls had had their fun and now I

would have mine.

I did not say anything about bloodshed when

I was talking to Jim

Clark. I never had but one

conversation with Jim Clark

about this matter. On the

evening of the shooting I tried

to borrow Jim Clark's gun. I asked Jim

Clark that afternoon if he

had a pistol. I wanted a pistol or gun

at home. I wanted

them for use. I did not want to kill a

dog. I wanted to

kill anything that needed killing. I

wanted the pistol or gun to

kill a human being. I don't know who

it would have been. Some one had

been carrying off the wood.

"Josie first told me of her troubles

something over 2 months ago.

It was at her request I had kept

quiet. She asked me to tell him

on Tuesday. I asked the old man on

Sunday night where he would be

the next day as I had a great secret to tell

him. Josie's

troubles were what I referred to.

Josie did not ask me to tell

him on Tuesday. I saw him on Monday

but did not tell him because

she had not yet told me to do so. Josie told

me to tell him on Tuesday

morning. That was at her home.

Defendant was not

there. It was in the forenoon.

"Frances was in another room.

Josie, Frances and I were not

friendly at this time like we had

been. Frances had called me a

liar, but Josie had not. For 2

or 3 days we had not been as

friendly as we had been, but we had not been

quarreling.

Josie and I had never had a row.

"Mrs. Surghnor came up when Frances and I

were having a row, Josie was

present. It was about some letters

that they said had been taken

out of Frances' trunk. They were

Frances' letters. I said

in that quarrel that I was going to make a

little hell myself. I

did not say "I didn't' care a d--m how many

letters Frances got, I only

wanted Josie's letters,' nor did I say

anything to that effect.

"For about a week before the killing Josie

and I had not been as

friendly as we had been. It was not

more than 3 days before the

killing when the rows between Frances and I

came up. It was not

these rows that I referred to when I was

talking with Jim Clark.

When I referred to the girls having their

fun, I meant Josie and

Frances. I had had no rows with the

girls before then.

"I am 26 years old. She, Josie, when

she told me to tell her

grandfather of her troubles was not as

friendly as she had been, but

then she had not lost confidence in

me. It was about noon 2 or 3

months ago that Josephine revealed her

secret to me. No one was

at the house except she and I."

Very little more was developed in the cross

questioning on the part of the state.

Mrs. Dan Surghnor, when placed on the stand,

said: "I have observed a

change in the actions of Mr. Regnier,

especially since the Tuesday

before the shooting. After Sunday I

noticed that he walked a

great deal in the yard, whittling

a great

deal. He seemed to have no aim

or purpose in walking about

the yard. It looked as if he were in a

deep study. I can't

say that I paid much attention to this up to

Tuesday evening.

"On Tuesday afternoon I told Mr. Regnier

about some difficulties that I

had witnessed between his daughter, Frances

and Ben Simpson, and also

between Josie and Simpson, and told him if

he didn't stop Ben Simpson

from aggravating the girls they would leave

home. Frances had

already threatened it. He seemed

struck speechless; turned

white. He never gave me an

answer. This was late Tuesday

afternoon, the day before the killing.

"I regretted having said it, because

it seemed to worry him as it

did. I noticed that after supper that

he still walked in the

yard. It was about bed-time when I saw him

last walking in the

yard. This was about 9 or 10 o'clock;

it might have been after 10

o'clock. Sometimes he would sit down

in a chair and then get up

and start to walking again. "I last

saw him when I went out to

put the horse in the stable that

night. I saw him about 1 p.m. on

Wednesday, the next day; he was standing

with his head leaning on his

hands, which were upon the picket fence at

Mr. Taylor's store, which is

just across the street from where I

live. No one was with

him. He stood there until I drove past

him and spoke to

him. I stopped the buggy. He

never spoke until I

spoke. I told him that I regretted

that I had spoken to him

about the row. He said, I think: "He

will not bother us any more;

I'll kill him first." Referring, I

supposed, to Ben

Simpson. I never saw the defendant

again that day. On

Monday when I spoke to him about the hydrant

he gave me what I thought

was a very short answer. I was not at

home when the shots were fired, but

got there just at that time. I did not

hear a conversation

between the defendant and his wife the day

of the killing. He had

never spoken short to me before Monday."

Mr. Bliss, one of the attorneys for the

defense, in arguing the right

to introduce the testimony of Mrs. Surghnor,

as to the condition in

which she believed her statement about the

quarrels between the girls

and Ben Simpson had placed the mind of the

defendant and his subsequent

half threat to kill him (Simpson) if he

persisted in bothering them,

said it was relevant, because it showed that

it was not improbable that the

defendant had gotten the pistol with the

intention of killing

Simpson, instead of his granddaughter. The

court adjourned at 5:30 p.m.

until Monday afternoon at 2 o'clock.

The Sunday Gazetteer

Sunday, July 24,

1892

pg. 1

ANOTHER MURDER

A Man in Sherman

Shoots His Granddaughter

The Gazetteer

is called upon to record another

cold-blooded murder in this

county. Late Wednesday afternoon

Albert Regnier, of French extraction, living in

Sherman, killed his granddaughter, Josephine

Gremeau, aged 17 years.

Regnier was heard to abuse the girl on the

street during the afternoon, and

after he was arrested told the officers that

the girl had disgraced the

family, and that he would rather be in

prison than be disgraced.

He got a revolver

at Lindsay's second-hand store, claiming he

wanted to kill a dog. He went home and

commenced his bloody work on the poor girl, who is

believed to have always been pure and

virtuous. The first shot missed her,

and she fell on her knees begging for mercy,

but another ball pierced her

heart and still another entered her

breast. She lived only about 2

minutes.

After the shooting Regnier deliberately

walked up to the square and

surrendered to Deputy Sheriff Gene Andrews,

to whom he very coolly said: "My

granddaughter has disgraced the family and I

have

killed her, or at least I have tried to."

Deceased was not

quite 17 years of age, and had lived with

her grandfather, who had been

married twice, since she was a child of 4

years, at which time her mother

died and consigned her to the care of her

grandfather.

Mrs. Regnier, her

daughter, Mrs. E.W. Haskell and Miss

Frances Gremeau witnessed the

shooting. The young man who is alleged

to have caused the deceased

girl's shame was a boarder at the house for

quite a while. The Sherman

Register of Thursday states that

under instruction of the court a

postmortem examination was made. The

physicians reported

to the court

Wednesday afternoon that there was no

evidence whatever to support the

rumor which led to the terrible tragedy.

Thursday, after

the coroner's inquest, a friend of Regnier's

called on him, and to him Regnier made the

following statement: He said that Mrs. Regnier told him

on last Sunday the story of his

granddaughter's shame. He at once

pronounced it false, and afterward, when the

girl denied it, he believed

her. The subject was broached to him

several times and he was nearly crazy

with grief. On Wednesday his wife and

stepson again made these

charges. He again refused to believe

them, and Mrs. Regnier then said she

would get her daughter and son and prove

it. "That drove me wild," said

Regnier, "and I went up town to get a

pistol. I was crazy. When I came home

they were all there waiting. I again

asked Josie about the matter

and she said nothing. Then I

fired. I did not realize what I had done

until that night. They (meaning his

family) brought the whole thing on

and her blood be on their hands."

Bent Simpson

requested the Register to correct the

statement that Mrs. Haskell told him

of Miss Josephine Gremeau condition.

He states that Mrs. Haskell

never told him anything about it, but that

the young lady herself told.

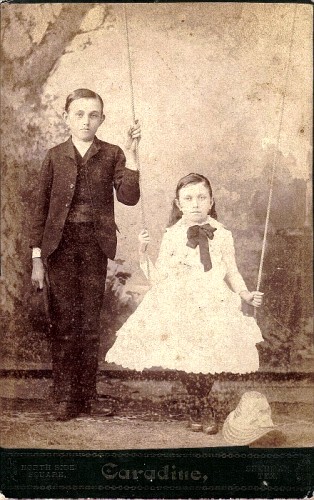

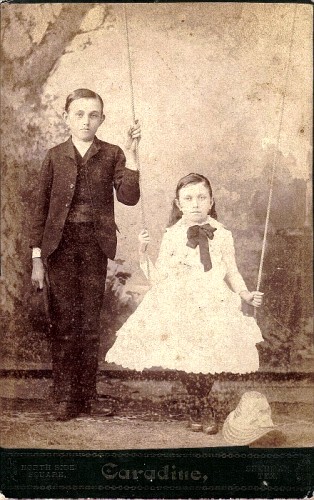

Joe, born

1874 & Mary Francis Regnier, born 1876

The Galveston

Daily News

Wednesday, July 27, 1892

pg. 6

THE REGNIER TRAGEDY

Defendant Held to Answer Without Bail

"The Unfound Story of the Girl's Ruin

Actuated Regnier to Do What He Did."

Sherman, Tex., July 25 - Interest in the

Regnier case still

continues. The defendant was brought

into the courtroom a few

minutes before 2 o'clock this afternoon and

before the case was called

held quite a conversation with his son, Joe,

who, with his sister

Frances, has been near him all during the

trial. Interest in the

trial and the fact that the cool courtroom

offered quite a contrast to the hot street

corners served to

make the crowd a large one early in the

proceedings this afternoon

Court called proceedings promptly at 2

o'clock. The attorneys for

the defendant held a short conversation and

a slight delay was

caused by the absence of Mr. Jameson,

attorney for the state.

Judge H.C. Head was the first witness placed

on the stand this

afternoon.

He said: "I have known the defendant maybe 6

years. He has talked to me

of his daughters. It was while I was

judge and was coming

home from McKinney. That was 4 or 5

years ago. I had not

known him very long then. [The state

objects because his feelings

toward them then might have changed.]

Our acquaintance was

slight at that time. He brought

up the subject of the

girls. He said, as near as I can

remember, that he was a

widower. He spoke of the 2

girls. He seemed to think

them smarter and better than other

girls. He spoke of their

education and welfare generally and the

general tenor of his conversation impressed

me that

he was very proud and fond of them. He

spoke of the

responsibility of raising 2 girls and taking

proper care of them.

"I cannot say that he spoke of royal blood

in the family, but I think

he spoke of his family being an old one of

high standing in France and

that his position there was not in keeping

with said family

standing. The main subject of

his jail

was his 2 daughters. I

can't say, but I believe I had met him once

before, this was either my first or

second time. I think he recognized me

as judge, and he came up

and began to talk to me. The

conversation was on the cars.

I did not notice that he was drinking."

The next witness placed on the stand was

Judge E.P. Gregg, who in

substance said: "I am acquainted with the

defendant, have known him 12

or 14 years. The acquaintance was

rather intimate; it began to be

intimate when he was a school trustee.

I was thrown with him a

great many times while he was a trustee and

have had business

transactions with him since then. He

always regarded me as a

special friend. He frequently talked

to me about his affairs in a

confidential manner. He was living

with his first wife when I

first became acquainted with him.

"He often talked to me while a

widower. He ofter spoke of his 2

little children, one of them I understood he

said was his

granddaughter.

This was after his wife's death. From

his actions and talk it

seemed that he thought a great deal of the

children. He often

spoke of them.

Recently when he was keeping a boarding

house, he said to me that he

wanted to quit the business to relieve the 2

children of the hard work

and worry. He didn't want them to have

to live such a life. He

always spoke of them in a fatherly and

affectionate way.

This was especially impressed upon me

recently when he spoke of the

boarding house being an undesirable place

for his 2 girls. He

said he wanted to get a home for them and

would rather work harder

himself.

"As county judge I married him to Mrs.

Simpson, who is his present

wife. I never heard him speak unkindly of

any member of his

family. He spoke to me frequently of

the standing of his family

in France. In this he had a great

pride. (Upon this the testimony

of Judge Gregg was pretty much the same as

that of Judge Head.)

This frequent reference to his family

created the impression upon

me that he was foolish or rather silly upon

the point. (The state

objected and the defense said it proposed to

show that it was a mania

with the defendant.)

"I was especially struck with the old man's

feeling toward his family

when a son was recently arrested for some

offense. He seemed to

be fearfully hurt and declared he would

rather see him dead than in any

such trouble if he were guilty. That

was, I think in December

last. The boy was put in jail.

He came to me about it and

seemed almost wild. I don't think I

saw anyone who seemed to feel

the humiliation more deeply."

Dr. S.F. King was placed on the stand and

said: "I am one of the

physicians who conducted the autopsy on the

body of Josephine

Gremeau. I did not examine the body

for the wounds which caused

the death."

Capt. J.D. Woods said in substance: "I have

known the defendant, I

think, 2 or 3 years. I was

employed by him in last December

to defend his son who had been arrested upon

a writ from

Freestone county. He seemed to

be very much broken down and

it took me a long time to find out

what he really did want.

I finally learned that his son was in jail

and he wanted me to go and see

him. I could not find out anything

else from him. I asked him why he

didn't go and he said he didn't

was to see him until I found out anything

else from him. I went

and reported to him the next day. Then after

that he and all the family

went to see the boy. I told him I

didn't think there was anything

in the case. That seemed to quiet him

right down. I didn't

know when I first went there that the old

man had been there. I

learned that afterward. His son

was charged with

embezzlement. He had been working on a

newspaper at Wortham.

"I have a great deal of experience in

defending people charged with

crime. Have noticed that there is often a

great deal of agitation on

the part of parents when their children are

arrested and wouned or

charged with a serious crime. It is

peculiar for a parent to be

concerned under such circumstances.

His agitation was beyond what

is usual. It surprised me. I

have possibly seen mothers

agitated as badly as he, but not a father."

Mrs. Surghnor being recalled, said: "I

washed the body of the

deceased. I examined the location of

the wounds carefully.

I noticed 3 openings from wounds - 2 in

front and 1 behind. The 2

in front were very close together and about

the middle of the

breast. The wound in the back was

about the lower point of the

left shoulder blade. There were

no wounds in the side. At first we

thought, before undressing her,

that she was wounded in the left side, but

found it was a clot of

blood that had dropped down and had oozed

out and discolored the

dress. When I undressed her I found

it was a mistake and

that she was not wounded in the side at all.

The deceased was about 5' 10" in

height. She was a rather large

and well developed woman. [Here

witness described how the trunk

was sitting and the direction from which 2

balls had entered it.

The position of Regnier and the girl at the

time of the shooting has

heretofore been given in evidence.]

Neither party could have been

in the door, they must have been in the

room. [Here witness said

that the house had been broken into last

night as some of the articles

had been moved out into the middle of the

floor. The windows show

that some one had effected an entrance into

the house last night. The house had

been securely locked. Here

Miss Regnier said to the reporter that the

keys to the house were in

her possession last night and that no one

had intimated a desire to

get into the house.] The witness

resumed.

"There is a hole in one sleeve which is

burned and in my opinion must

have been made by a bullet. I think

one of the shots must have

missed her."

Miss Regnier states that she thinks the

trunk had been opened but does not know that

anything had been taken.

Witness said: "I did not see the

shooting. I was not called in

as an expert to examine the bullet

holes in the

trunk. I saw the bullet

holes yesterday. Miss

Frances Regnier was with me."

The witness could only give her opinion as

to how many wounds.

She believed the wound in the back was made

by a bullet which passed

through the body. She did not

particularly regard the defendant

as insane.

"It is my opinion that the man was out of

his senses from Tuesday until

after the killing. I don't believe he

knew right from

wrong. If he knew he was killing her I

am satisfied he knew he

was doing wrong. I thought he gave me

a very short answer at the

hydrant Monday afternoon. I think he

was in his senses though at

that time. He was walking

and whittling as if worried

Tuesday morning. I thought he was out

of

his senses later on Tuesday because he

looked it and the remark he made

indicated it."

Miss Lucian Norton being called back to the

stand gave in her

testimony as to the finding of the

bullets. It did not differ

materially from that of Mrs. Surghnor.

Miss Hattie Collins was placed on the stand

and gave some corroborating

evidence as to the finding of the 2 bullets

in the trunk and described

the rag about one of the bullets being of

the same color as that of the

jacket of the dress worn by Miss

Gremeau. She thought this bullet

was of 45-caliber. She had seen this

bullet Thursday.

Warden McKinney of the Houston street prison

was placed on the stand.

He said: "I know the defendant.

I know his son, Joe, when I

see him. I was in charge of the county

jail in

December. Joe was in jail; I saw

his father when he came

down to see him. I went to the cell

with him. He looked at

his son. He turned away from the cell

and did not say

anything. That was before Capt. Woods

had seen him (Joe). I

do not remember whether he came back

any more."

The defense here announced they had

closed. After waiting for a

witness who could not be gotten readily the

state closed. It was

submitted without argument.

The defendant was held to answer without

bail, stating that evidence on

the point of insanity was insufficient to

permit bail. He hit the

witness Simpson some hard raps in delivering

his opinion, stated that

he believed that the story told by him to

Regnier was wholly without

foundation and was what actuated the old man

to do what he did.

But he should have controlled his anger and

madness and not have

committed the terrible deed.

The Daily

Hesperian

(Gainesville, Texas)

Tuesday, July 26, 1892

pg. 3

REMANDED WITHOUT BAIL

Ilbin [sic] Regnier Has His Preliminary

Hearing

Sherman, Texas, July 25 - [Special} - The

preliminary hearing of Ilbin

Regnier, who shot and killed his

granddaughter while pleading for her

life, closed at 5 o'clock this

evening. Regnier was remanded

without bail.

Defense attempted to prove insanity, and

that Regnier's stepson, Bent

[sic] Simpson, had slandered the girl and

was the indirect cause of the

killing. In his charge the court

scored [sic] Simpson and said:

"Do not believe one word of his testimony;

think him the prime cause of

the trouble."

The La Grange

Journal

(La Grange, Texas)

Thursday, July 28, 1892

The killing of Miss Josephine Gremeau at

Sherman, last week, by her

grandfather, Albin Regnier, was a lamentable

affair. The old man

killed her because he believed she had

brought disgrace upon his

family, which belief, it turns out, was

based upon statements made to

him by his step-son, Ben Simpson, and were

untrue, as shown by the

report of the physicians who made the

postmortem examination. From all the

testimony adduced at the inquest The Journal

believes that Simpson is a

villain, and had some ulterior purpose in

view in making the false

statement he did. Should it prove true

he deserves to be ex----

by all good people.

The Sunday

Gazetteer

Sunday, November 6, 1892

pg. 1

ANOTHER MURDER TRIAL

The trial of Albin Regnier, charged with the

murder of his

granddaughter, Josephine, at Sherman

in July last, was called

in the District court at Sherman early in

the week. Owing to the

disability of Judge Brown, Judge Wood was

selected by the bar to

preside. Twelve jurors were secured

Wednesday and the trial

opened. The Sherman Register

says that the old gentleman seemed greatly

disturbed and during much

of the time he would sit with his face in

his hands silently

weeping. The evidence of Mrs. Francis

Regnier, who died a few

days since had been taken down in writing,

was submitted to the jury.

Mrs. Bird, who lives near the Regnier

residence in south Sherman,

testified that she was passing on the

opposite side of the street when

the shooting occurred. She heard Mrs.

Regnier say: "Don't kill my

dear child." Regnier said: "Yes, I'll

send her to h--l."

She heard the shooting and saw Regnier come

to the door and hear him

call, "Francis, come here to me." She

did not go and Regnier

said: "I will kill you before the sun goes

down." This was

entirely new evidence, having never before

been offered in court.

The case was given to the jury Thursday

evening and at 4 o'clock they

retired. The jury remained out many

hours and finally the foreman

announced to the judge that it would be

impossible for them to agree.

Saturday, January

28, 1893

pg. 6

SHERMAN SIFTINGS

Sherman, Texas, Jan. 26 - The case of Albin

Regnier was called on a

motion to reduce the bond to $200

[sic]. The court refused to

hear the case except on a writ of habeas

corpus and such a writ was

sworn out. The prisoner when brought

out gave unmistakable signs

of failing health and seems to have aged

rapidly since his

incarceration. The bond was reduced to

$200 on account of his bad

health. The defendant seems to despair

of giving the bond as it

is. Regnier's crime is the shooting to

death of his

granddaughter, Josephine Gremeau, in this

city last summer.

The Galveston

Daily News

Monday, January 30, 1893

pg. 2

RELEASED ON BOND

Sherman, Texas, Jan. 29 - Abbin [sic]

Regnier, who has been in jail

since July last on the charge of the murder

of his granddaughter,

Josephine Gremeau [sic], was released to-day

on $2000 bond.

The Sunday

Gazetteer

Sunday, February 5, 1893

pg. 1

Albin Regnier, the aged carpenter, in jail

in Sherman charged with

killing his granddaughter, has been released

on $2000 bail.

Regnier is in bad health, and informed the Sherman

Register

he was going north to visit relatives until

the date of his trial, when

he will return. He has been tried

once, the result being a

hung jury.

|