By CORA BELLE BICKFORD

Foreword.

This is the first time that the story of Martha Smith of Berwick has been

offered for publication. It has been obtained only through much research among

personal papers, in church records, in state archives, and it should be said

that descendants living in Massachusetts to-day have helped to make possible the

gathering of this material. The story, connected as it is with historic

happenings that so greatly affected the lives of colonial representatives of

rival nations in the New World, is of far more than local interest, while the

heroic endurance of this pioneer mother must forever remain a monument to the

true worth of Woman. C. B. B.

ON A PERFECT June morning in the year 1677, a bridal party lingered before the open door of the log house of Thomas Mills of Wells. The house, on an elevation of land, stood well back from the highway that, by the order of the court, had just been completed at the outbreak of King Philip's War. This road, leading from Saco to York, was continued along the coast that it might better protect the inhabitants, in their necessary journeys, from sudden attacks of the Indians, at the same time giving easy access to the ocean by means of the rivers and streams that flowed seaward. With this consideration it had been continued even to the center of habitation in the province of Massachusetts, and with the yearly growth of the colonies it was coming to be much travelled.

The house faced a broad clearing through which one could see a stretch of sparkling blue ocean with broken hillocks and ridges of sand, heaped here and there by the action of the winds, serving as a barrier to encroaching waves that broke in long lines of feathery whiteness at their feet. On either side of the clearing were forest slopes clothed with varied shades of green, the soft, light foliage of the birches and poplars contrasting with the richer coloring of the maples and elms and these, in turn, clearly defined against a darker background of pines and firs.

A light southwest breeze was abroad. It came hurrying up the hill, gently tossing balsamic odors gathered from the woodland, the delicate fragrance of wild blossoms and a salty exhilaration that could have been the gift of none other than old ocean. Stirring the grass leaves of the soft green sward in front of the house it crossed to a belated crab-apple tree, rosy with bloom, and, rouguishly shaking its branches, sent down a shower of tinted petals upon the head of the young bride standing directly beneath, then passed on to pay its respects to the garden-plot at the side of the house.

In this garden-plot grew mullein pinks, bouncing bets and daffodils. Hollyhocks were sending up tall, pale-green stalks and leafing marigolds were getting ready to flower. There was southernwood, too, with its clean, pungent odor, or lad's love, gillyflower and larkspur already in bud with violets and sweet herbs. It was a garden that in its simplicity reminded one of old England, for Thomas Mills, Exeter-born, had brought from Devonshire, then as now the garden spot of the British Isles, a true love for flowers. Having obtained his grant, he cleared the land, but before he built his house, he tucked seeds away in the rich brown earth, seeds that were the most precious treasure brought from his old home across the sea. These sprang up and blossomed, giving in turn seeds for newer gardens, each year's blooms vying in brilliancy with those of the year before.

The most distinguished member of that wedding party was Rev. Shubael Dummer of York who, less than two hours before, had performed the ceremony that had given Martha Mills to be the wife of James Smith of Berwick. He had been sent for, rather than John Buss, physician-preacher, who for such duties was usually called by the people of Wells among whom he labored. But at that time the name of John Buss was under a cloud and Thomas Mills was a proud man. He was proud that he was an Englishman, prouder that in his adventurous trip to the New World he had acquired such considerable property, but proudest of this daughter than whom there was not one fairer for many a mile. This was the last thing he could do for her in his own home and he meant that there should be sufficient dignity attending the marriage, a dignity he felt was well sustained when he looked at the Rev. Dummer in his wig and gown.

Mary Mills, the mother, another one of the group, possessed a pride of quite a different nature. Had she not trained this daughter until no bride ever went forth to her new home more richly dowered with practical knowledge? No one could turn a smoother web from the loom; she had taught her the art of soap-making as she had learned it in the home town of Bristol. Martha could cook an Indian cake, fry a fish and roast potatoes in the ashes to perfection, dishing up as economical and appetizing a meal as ever hungry man sat down to. With her needle she was deft; and arts that her mother had learned in England had been taught her, so that her wedding gown boasted a border that well might be the admiration of any colonial girl. Mary's pride reached its height when she thought of the marriage Martha had made. James Smith of Barwic had held his grant nine years, 40 rods of land on the Newichawannock river and more than 100 acres in all. The home to which he was to take his bride was one of the most substantial and best furnished in that settlement, much of the furniture having been made by the groom's own hands. Then he had come for Martha, sitting straight and strong on his horse; and she was to go away with him, sitting on the pillion behind, with some of the most precious of her dower stowed away in bags beneath.

Martha could not know of the pride that was in her mother's heart, but she felt the comfortableness of being approved. Her wedding gown of flax-colored linen had a pattern in scarlet thread worked above the hem of the full skirt; the thread dyed after a formula given by a friendly Indian before the outbreak of 1675. The close-fitting cap that covered her head and from beneath which a rippling strand of sunny brown hair had escaped was of the same material, the same scarlet border giving it becomingness. Her low shoes, the gift of her father, had leather soles with tops of cloth, fitting so neatly that hem of gown never cleared a trimmer-turned foot and instep. "With fresh complexion, deeply tinted cheeks and lips and clear grey eyes sparkling with hope and courage, she was, indeed, a comely bride.

Beneath one heel of her shapely foot a piece of southernwood was being crushed, for Martha remembered that:

One who hides within her shoe

A piece of southernwood or two,

May hope to meet

Pleasant experiences.

Another member of that bridal party was Thomas Mills, Jr., a lad of sixteen years, who had been watching the others with sober countenance and responding to the request of little Mary, scarce eleven, who had been coaxing him from the shelter of her mother's skirts to break some branches from the apple tree.

But now the time had come to go and Martha gave her hand to her father, curtesied low to the Rev. Shubael Dummer and touched her mother's cheek lightly with her lips. It was her brother's turn next and, drawing down his head, she whispered something in his ear which caused him to blush and brought a smile to his serious lips. Now it was little Mary's turn, but she did not wait for Martha to make the first advance. Throwing her arms about her sister's neck, she held her while she pushed the stem of a cluster of apple-blossoms beneath the border of her cap. Then, releasing her, she tucked another spray into the fastening of her bodice, whispering:

''It is for my sister and I love her."

It was all so quickly done, and Martha's eyes filled with tears as she drew her little sister to her with a tender caress.

There was no longer time for delay; for the sun was climbing high in the heavens and the day would be well spent before the new home in Barwic would be reached. James Smith followed his wife in his good-byes to the family and the reverend gentleman, then, lifting Martha to the pillion, he sprang up in front of her and down the hill they rode together with backward waving of hands until they came to the little bridge at the level of the highway, where the water of a bubbling spring went trickling away to find companionship in some near-by brook.

Here willows fringed the road and just before James Smith and Martha passed beneath their branches, Mary Mills suddenly and adroitly turned the attention of the group on the hill in the opposite direction by exclaiming: "Look, Thomas, what makes the breeze shake the pine tree so strangely?"

Then she could not suppress a smile at the thought that her ruse had been so successful. While the day with its beautiful weather was good omen, it would never do to watch a dear one out of sight ; no good luck would be likely to follow.

And Martha Smith, respecting her mother's superstition, did not look back when they had reached the willows. Turning her face resolutely away from the privilege of a last glance at her old home and the familiar faces, she looked straight before her and so rode with her husband, away and across country.

* * *

Settlers of Berwick, to-day an important town of York County, Maine, were, many of them, adventurers. Influenced by rumors of the great wealth of the New World and eager themselves to be acquiring earthly possessions, they had crossed the Atlantic to cast in their lot with other as hazardous fortune-seekers as themselves. In many cases the fortune materialized and the young man soon found himself proprietor of wooded acres and mayhap a clearing in which stood the house that was to be the home of his future bride.

To this last class belonged James Smith. His first grant of land, recorded in 1668, showed that it lay on the east bank of the Newichawannock, along the river for an eighth of a mile, then running inland with wooded slopes and outbreaking rocky elevations. It was to this comfortable home, in a spot that he had cleared, a dozen rods or more from the river, that he took Martha, his bride.

From the house the land dropped gently down to the water's edge where there was a small landing and during the open season a small boat was usually hauled up on the shore or, perhaps, tugged at its moorings when the current was strongest. The river was always flowing, flowing, on its way to the sea and its course was, farther on, through the marshes where it might be seen on a sunny summer day blue with tide-water, then moving on to be lost in the broad, consequential Piseataqua.

It was this river view that Martha loved best of all on the farm, and she often stood at the side door of the home and looked away towards the southwest. As far as eye could see, she could follow the river in its course, then dream about it as it found its way into the restless ocean. The spirit of her ancestors flowed in her veins. Her thoughts were not held by the boundary of that ocean, and she often longed to see that other land about which her parents and husband talked.

Yet she was content with her home and the life that it afforded. Like her husband, she was ambitious and whenever he came to her with the details of another profitable transaction, or talked to her of added acres, her heart responded sympathetically. No man loved an advantageous deal better than he, but he was a tiller of the soil, a laborer as his services were needed, and also a man of affairs. And while he worked out-of-doors Martha put the acquired skill of her girlhood to best account in the home.

Scattered as were those colonial homes, there would have been many lonely lives had not the majority of the inhabitants looked upon life philosophically, allowing happenings of whatsoever character, to entertain or amuse. The passing traveller brought the news; and he was always welcome. He would tell of births, deaths, the findings of the court that dealt with the eccentricities or the short-comings of neighboring settlers — all a part of the panorama that fed curiosity and gave human interest to life. Such a visitor brought a gathering from the homes in the neighborhood and when gossip had been exchanged all regaled themselves with blackberry wine and molasses cake.

Occasionally a piece of news called forth general ridicule as when William Furbish of Wells was reprimanded by the court for abusing his Majestie's authority (Charles II. of England) when he used opprobrious language in calling his officers "Devils and Hellhounds."

Sometimes indignation stirred the whole settlement. This was true when James Adams enticed the boys of Henry Simpson, as he believed, to their death. Building an enclosure of logs, inhanging so that they could not be scaled, he entrapped the lads there in the midst of a desolate forest. But they dug away the ground with their hands and escaped, finding their way back home after being without food and water for several days.

John Wincoll, who owned a farm farther up the Newichawannock, brought the news that the Simpson boys were liome, coming up the river in his flat-bottomed boat, shouting as he went along.

"Ho-ho, Simpson boys h-o-m-e ho-ho, Simpson boys h-o-m-e," all the way along, the settlers coming to the river bank to get the news, and to hear the finding of the court:

James Adams, found guilty of bad and malicious temper and revengeful spirit to receive "30 stripes well laid on, to pay to the father of children of Henry Simpson 5 pounds each, to pay treasurer of county 10 pounds, and to remain close prisoner during the court's pleasure."

This was the most grievous offense for many years and the matter was talked of for many a day and month, often furnishing material for an entire evening's conversation when there had been no important happening for some time.

Frequently conversation turned to the Indians, a common foe. King Philip's war had carried desolation into all New England. Persistent fighting had subdued the savages in Massachusetts, Plymouth and Connecticut, but in New Hampshire and Maine the Indian hatred of the whites continued to express itself until the treaty of Casco in 1678.

The Indians of this region were principally collective tribes known as the Abenakis. The French, having established relations with them through the missionaries, saw their opportunity and seized it. They persuaded many of these distressed and exasperated savages to leave the neighborhood of the English, migrate to Canada, where they settled first at Sillery, near Quebec, and then at the falls of Chaudiere. Jacques and Vincent Bigot were prime agents in their removal and took them in charge. Thus the missions of St. Francis became villages of Abenaki Christians," like the village of Iroquois Christians at Saut St. Louis. In both cases they were sheltered under the wing of Canada and their tomahawks were always at her service. But though many of the Abenakis joined these mission colonies the great body of the tribes still clung to their homes on the Saco, the Kennebec and the Penobscot.

But there were pleasures of a more wholesome nature to keep the settlers' minds well balanced. Sometimes Martha would ride down to York with James where they would cross the ferry at Goodman Hilton's, James swimming his horse across and Martha paying one penny to go by boat. On the other side Martha would mount again and they would go on to visit with the Moultons and the Littlefields. Sometimes the journey was made to Kittery where one got news direct from incoming ships and met friends coming over from England to settle.

None in the settlement had a happier and more comfortable home life than Martha and James Smith with their sons and daughters about them. James, Jr., was the oldest and then came the daughters, Mary and Elizabeth. Baby John, born July 26, 1685, was the youngest. When he was nearly five Martha was 37, yet the years sat lightly upon her. She was a woman of great attraction, as the personal charm of girlhood blossomed into the full beauty of motherhood.

So the life of the colony drifted along until the winter of 16891690, a season of so much snow that travel was greatly interrupted. The heavy drifts kept the women and children housed and the men loved to gather about open fires of logs piled high and relate deeds of prowess as they had heard them both in the New World and the Old. In December news came of the forts taken on the Kennebec, the 16th of November, but the extreme cold and snow lulled the inhabitants at Salmon Falls and Berwick into a sense of security. They believed that they were so near the coast, and within such easy communication with Massachusetts that all would be well with them, though the Indians were abroad.

So little precaution did they take that the one fortified house was not occupied and no watch was kept at either of the stockaded forts. The gate of one of the stockades hung by one hinge, left open by a miscreant youth when the first snow came in the fall; and pushed by the winds and the drifts and weighted by the snows that fell upon it, it sagged out of usefulness and waited for spring to come that it might be repaired.

The year 1690 came with no change and thus passed the months of January and February. March was blustering and stormy for the first two weeks, but spring set in early. The soft winds helped the sun, running higher and higher, to start the burden of snow; the men roused themselves from the lethargy caused by the extreme rigors of the winter and the housewives were thinking of spring work in homes and gardens.

The 26th of March was a day like to summer with its blue sky and balmy air. The marshes lay warm in the sun, and the river, free to make its way to the sea, was bearing along the last portions of the icy rim that for weeks had marked its outline.

Martha Smith came often to the door that March morning. She watched Baby John at his play, building ditches and sluiceways that the water might drain off to the river, and she came again when he called: "Mother, come see." She came to direct Mary and Elizabeth how to push the leaves away to see if the daffodils were coming up, and once she stopped to call to the son, James, telling him, as he hurried away in the direction of the nearby woodlot, that dinner would be ready a half hour earlier than usual.

In the evening twilight she came again to linger long, watching the lights as they faded from the western sky. A mist came creeping up from the sea, there was a delicious saltness in the air and — what was that she heard, a bullfrog croaking in the marshes? — It had sounded strangely like an Indian call and a great fear clutched her heart for the moment. Somehow she had felt a strange unrest all day although there was so much of spring in the air and life seemed full of hope. Surely there was nothing to fear and she turned to prepare the children for bed, for all had promised themselves to be up early next morning.

* * *

"Pas de quartier aux Anglais!"

"Nous plantons la croix de Jesus !"

"Nous gagnons au nom de Frontenac et de Nouvelle France!"

The oaths rang out on the frosty air while the little bell in the chapel of Saint Francois echoed these pledges with clear, ringing strokes. On that winter morning wives and mothers had gathered on the shores of the Saint Francis river to greet the expedition as it came across from Three Rivers and passed on its way up the St. Francis, stopping only long enough for oaths to be renewed. Though there were many heavy hearts among the watchers on the shore, no tears were shed ; for was it not for France and a holy cause that the sacrifice was being made?

Of the three parties of picked men sent out by Count Frontenac, governor-general of Canada under Louis XIV. of France, in the year 1690, one was formed at Montreal, one at Three Rivers and one at Quebec. The first was to fall upon Albany, the second to direct its efforts against the border settlements of New Hampshire and the third to attack the settlement in Maine. By the glorious achievements of these expeditions directed against the English, under the combined forces of the French and Indians, Count Frontenac was to retrieve his fallen fortune. He was to aim a blow at his enemies that would help him to reclaim his allies and restore to him sufficient glory to demand the respect and special recognition of his sovereign who had once severely criticised him.

The second of these expeditions, aimed at New Hampshire, left Trois Rivieres on the morning of the 28th of January and was commanded by Francois Hertel. It was made up of 24 French, 20 Abenakis of the Sokoki band and five Algonquins. In part, the French were young sons of landed proprietors who held seigniories along the St. Lawrence and her tributary streams. In the company, too, were Hertel's three sons and his two nephews, Nicholas Gatineau and Louis Crevier.

A prominent figure of this expedition was young Louis Crevier, oldest son of Jean Crevier, who held a large seigniory at Saint-Franeois-du-Lac and he was the pride and the hope of the house of Crevier, Both strong and brave, he already had training in the attacks made by the relentless Iroquois who looked upon the Algonquins and their friends as eternal enemies. But this expedition lay far away from home and one heart was sad because of the departure. The seigneuresse of Saint-Francois-du-Lac yearned over this, her eldest born now living. During the days of preparation she prayed often in the village chapel and many times a day before the crucifix, and to the Blessed Mother she sent up hourly petitions that her boy might be safely returned to her. She saw that the scapula he had worn upon his breast since his first communion was attached to a newer cord of leather and she hid a tiny Agnus Dei in the inner pocket of his blanket jacket. She aided every preparation and at the moment of departure she placed her hands upon the shoulders of her boy and looked long into his eyes. Then he realized that he had his mother's blessing.

The party, leaving the village, moved up the St. Francis river to Lake Memphremagog, marching by long day journeys, though the conditions were much against them, and the heavy snows of winter a great handicap. From the lake they struck into the Upper Connecticut valley, then swung off to the southeast and headed for the coast. At night they camped under vigilant watch, for enemies were ever abroad and the winds might carry secrets.

They marched on snowshoes, each man with the hood of his blanket-coat drawn over his head, a gun in his mittened hand, knife, hatchet, powder-horn, bullet-pouch and tobacco-bag at his belt, a pack on his shoulders and the inseparable pipe hung at his neck in a leather case. The provisions they dragged over the snow on Indian sledges. The Abenakis took the lead; they knew the way well. So they pressed on, day after day, winter storms and melting snows retarding their speed, until it was two months before they came to the outskirts of the frontier settlements they sought - Salmon Falls and Berwick.

On the evening of the 26th of March they lay hidden in the forest that bordered the farms and clearings. Scouts were sent out to reconnoitre and found a fortified house unoccupied and two stockaded forts, built as a refuge for the scattered settlers, but no watch in either. The way looked so easy that Hertel passed the remainder of the night putting his party into three divisions and in giving full directions as to movements.

The attacks came just before break of day when the settlers were still deep in slumber, and the onsets were simultaneous. It was the hush before the dawn when the air was pierced by the first terrifying yell; then all was confusion. With no one on watch at the forts, there was no one to give the alarm and when the French and Indians burst in upon them with fiendish outcries that seemed to set the very stars in heaven vibrating, the settlers were paralyzed with fear, unable even to gather for defense. It was a short struggle; the assailants were successful at every point.

It would be impossible to describe the horrors of that massacre. Thirty persons of both sexes and all ages were tomahawked or shot, among them the husband of Martha Smith. Her oldest boy, James, escaped. It may be that her two daughters were killed. But Martha herself, with her little son John, not yet five years old, was among the forty persons carried into captivity. The foes then turned their attention to the scattered farms, burned houses, barns and cattle, laying the whole place in ashes. It took only a few hours to accomplish the deed, and when the sun was still high in the heavens preparations for the return march were made. Already was the expedition headed for Canada when two Indian scouts brought the word that a party of English was advancing from Portsmouth and the march was quickened. But the French and Indians were overtaken at Wooster river, a few miles up the Newichawannoek. There was a brisk engagement at nightfall in which, besides an Indian, young Louis Crevier, the oldest son of the house of Saint Francois-du-Lae, was killed. There was no time even to consider the dead and wounded; with the recruited body of settlers pressing hard, the retreat continued.

Then began that cruel march towards Canada. The captives, insufficiently protected, shivering with cold and suffering from hunger upon that long tramp, were forced through melting snows nearly to their knees, through mud and water, over long, icy stretches. If the weak fell by the way, they were tomahawked; the laggards were prodded on by the thought of the frightful death that might await them, and even the bravest grew so sick and weary that every breath was a cry to God to save. Almost blinded by the snow, with hands and feet chilled almost to freezing, with they knew not what before them, they kept on.

Among the bravest of these was Martha Smith. During all the scenes that had taken from her loved ones and home, no weak cry had escaped her lips. The fortitude that had been hers in every circumstance of her life, stood by her now. She carried herself with a dignity that must have impressed even the savage brutes who held her prisoner. Unflinchingly she looked straight into the faces of her foes and, day after day, holding little John in her arms or letting him trot by her side, went resolutely on. She saw her friends and neighbors struck to their death; she watched the weak grow weaker and the sobs of little children filled her heart with fierce pain, yet her enemy did not know; she was still unconquered.

It may be that this apparent fearlessness had saved her life and little John's on that fatal 27th of March. While he was sobbing out his baby wails of "Mother! Mother!" she bent over him, hushing his cries, and telling him that nothing should hurt him. Then, straightening up, she had looked straight into the infuriated face of a savage with tomahawk uplifted. But behind the face of the Indian was that of Louis Crevier and the arm was arrested before it had time to strike the blow.

In the retreat Hertel led his men and their captives to an Abenaki village far up on the Kennebec, very likely where Norridgewock is to-day. Here they got word that Frontenac's third expedition, that had been directed against Casco, had lately passed southward and the French leader and 36 of his followers started out to join them, leaving the captives in the Indian village until their return.

It was this period of rest that saved many of the heart-sick captives; for when the last lap of that journey towards Canada was begun, summer was at hand and the way was less hazardous. The season brought with it warm winds, sunny skies and beauties of nature that for a time diverted the thoughts from the sorrows of the past few months.

What would be their destination when the end of the journey was reached, was an unanswered question among the captives and Martha could not have known that she was to be taken to the home of the dead Louis Crevier. Since this was so, it is evident that she was to have been his special prize. By an unwritten law of such forays, each man of the expedition, Frenchman or savage, was given one captive as his personal property. These captives were not prisoners of war but "esclaves" (slaves), being simply a part of the booty, thus accounting for the wide distribution of prisoners once they reached Canada. This, also, explains why so many of them were left in Indian villages.

It was well that Martha could not foresee the result of that journey since it was to offer her the last drop in her cup of bitterness; when fifty miles from Montreal and some miles from Saint-Francois, Baby John was taken from her. That she was allowed to take him in her arms and whisper a good-bye instruction to be a good boy and not cry, but to do as his leader told him, was through the kindness of Hertel, himself, a privilege for which she felt always thankful. But her heart was breaking. What mattered it now what the future had in store for her?

That the lord and lady of the Seigniory knew of the returning of the expedition, hours before it arrived, was evident, for a swift messenger had been sent on ahead. Since the late spring they had known the fate of their boy; their nephew, Louis Gatineau, had been sent on as a government courier to tell them the result of the expedition when Hertel first reached the Indian village on the Kennebec,

By some irony of fate it was a June evening, not unlike that when Martha, a bride, had entered the home prepared for her at Barwie, when they arrived at Saint-Francois. They reached the shore of the Saint Lawrence, where it widens into the beautiful Lac Saint-Pierre, just before the sun went down, its reflected rays trailing in splendor across the smooth blue surface.

When the boat pushed off from

the shore towards the island home of the Creviers, Marguerite stood before the

door, shading her eyes from the rays of the setting sun. When the boat drew into

one of the sheltered coves below the house, she walked slowly down the path to

meet the occupants, and Martha, looking for the first time into that strong,

sweet face that told of its own sorrow, knew that she had found a friend.

* * *

"Ma chere soeur. Que la Vierge Marie vous benisse."

Marguerite Crevier, the lady of the seigniory, stood looking down at Martha as she lay still sleeping on that first morning after her arrival at Saint-Francois. In repose the face spoke more plainly of her suffering and Marguerite breathed a prayer.

"Let her sleep," she said as she turned to leave the room, first stopping before a crucifix on the wall near the head of Martha's bed again to cross herself and say an Ave. Then, going to the rooms below and from there to the front of the house where the children, Jean Baptiste, 11; Marguerite, 7, and Marie-Anne, 4, were playing roll the ball, with shouts and bursts of laughter, she cautioned them that they must not wake the lady in the chamber above.

"La femme, elle malard?" asked little Marie, running to her mother's side and speaking in a whisper.

Marguerite explained that she hoped that la femme was only tired but she must not be awakened and then the children took their balls and went down towards the fort to play.

* * *

These June days, like all others of the year, brought many tasks for Damoiselle Marguerite, for the seigniory of Sieur Crevier, her husband, was one of the most important. Situated fifty miles below Montreal, where the Saint Lawrence river widens into Lac Saint-Pierre, it stretched for five miles along the shore. It had been obtained by him in 1673, with all the titles thereto appertaining, and here at the mouth of the Saint-Francois river, for many years he had been acquiring tenants as vassals until their narrow, lath-shaped farms formed a considerable settlement along the river front, reaching far inland.

His own buildings were upon a large, wooded island at the river's (Saint-Francois) mouth and here was a strong fort. The seigniory house was of stone, low and covering much ground, but substantially built with its interior of heavy, hewn timbers. On the ground iloor were several large rooms, one of which was the family gathering place. The flax and spinning wheels were here; Marguerite brought her sewing; here she taught her daughters to spin and weave, and here her husband came to talk to her about the proprietes. Together they planned for laying in provisions for the winter and talked over the needs of the mission six miles up the river or surprises for Father Louis-Andre when he should come on his quarterly visit. Here was a seat on the chimney bench for the old grandfather, father of Jean Crevier, when it was not warm enough for him to sit on the bench outside the door, and also a corner where an aged aunt of Marguerite sat with her knitting, talking to herself gently of days long ago in far-off France, or nodded in her chair, smiling as she dreamed. There were muskets on the walls and powder pouches; for always one must be ready for defense with the Iroquois about; and there were trophies, a bearskin that Louis had taken himself when a lad of 17, a bunch of Iroquois arrows and the beautiful branching antlers of a caribou and a buck.

While the family room was so closely associated with the life of the Creviers, other parts of the great manor house were important. There were the large kitchens where the family and the guests of the house ate. Usually it was a considerable family, counting the attendants, the soldiers at the fort and the members of the war expeditions who always stopped at the island when they returned from their forays, so that sometimes for weeks together the large dining-rooms were filled at meals. Then there were the provision rooms and the vault-like cellars, filled with supplies to last through the long, cold winter.

On the second floor were small, cloister-like sleeping rooms, each immaculate in its neatness, for Damoiselle Marguerite was looked upon as the most wonderful of housewives and home-makers by the inhabitants of other seigniories as well as that of Saint-Francois. And was it not as it should be? Was she not the daughter of Sieur Hertel de Rouville and a sister of Francois who had led the expedition, under Frontenac, into the settlement at Salmon Falls and Berwick? And were not both father and brother recognized as "brave, courageux et hommes de tete?" Marguerite Hertel, married now to Jean Crevier for 27 years, was yet but 41 years of age, young enough to have pride in looking after every task connected with the life of the household, while Jean, who had seen 47 summers, regarded his wife as exemplary in all that is womanly and capable.

This morning the Damoiselle had a new duty, the sister above stairs must be fed, and when she had set all the household attendants to their morning tasks, she prepared and carried to Martha's room a wooden bowl of steaming porridge.

As Marguerite entered the room for the second time that morning, Martha opened her eyes and sat up, then sank back, shading her face from the bright light of the morning. There could be only sign language between them, and Marguerite held out her hand as she approached the bed, assisting her to rise, then left her while she went for fresh water and a towel. For nearly three months Martha had tasted no really palatable food and when she had eaten she was physically soothed and again sank to slumber, from which she did not awaken until late in the afternoon when Marguerite came and led her to the family room below stairs.

Here she was greeted by the members of the family and a chair was placed for her. As the twilight made itself felt, little Marie came to her and resting her head upon Martha's lap, whispered: "Que je t'aime."

Though Martha understood no word, there was a heart language

that she could interpret and, reaching down, she took the child in her arms and

cuddled her as she would have cuddled Baby John had he been there. Reaching up,

the child put her arms about Martha's neck, and then was born a friendship that

saved the captive from many hours of despair in the days that were to come.

Martha's place in the household now became one of much usefulness.

Marguerite treated her more like a sister than a servant. She was left much with

the children and, caring for them, learned the language and their simple ways of

living. When she was not thus employed she assisted Marguerite with daily tasks

about the household and while her heart cried out daily for her son, she

realized that it was best for her to be always busy. "Why the world should hold

so much bitterness when nature was so beautiful, she could not understand.

* * *

But Martha was to experience other terrors. She had been in her new home but a few weeks when she again knew all the horrors of an Indian attack. It was at hand, what the old voyageur called "the time of the leaves and the butterflies and the Iroquois." They had come from the vicinity of Albany by way of Lake George, Lake Champlain, and the Sorel river, one hundred and fifty Iroquois thirsting for the blood of their brothers, the Algonquins, and of the French, who were the Algonquins' friends.

Before it was known, they had encamped on the very island where were the fort and the stockaded buildings of Jean Crevier, and it was one of the attendants who first gave the cry:

"Voici les Iroquois. Cachez-vous en surete; au fort! au fort!"

Jean led his soldiers with reinforcements from the mainland and attacked the enemy in its camp. It was a bloody battle, fourteen of the whites were killed and several wounded. The Iroquois were routed, but they carried with them four or five prisoners, among them Jean Crevier himself.

Now it was Martha's turn to act as comforter to the lady of the seigniory, who might, like herself, be widowed. Or the husband might meet a fate worse than death. In the weeks and months that followed, the two women became closely endeared to each other, and each day held some tender experience. But Jean Crevier did not return nor was he heard from.

November came, the saddest month of the year. The last of September there were preparations for the winter's supplies. Herbs had been gathered for salads and soups and packed with salt; the bins had been filled with vegetables and as soon as the weather became cold enough, venison, game, fowl and fish were frozen and put away in the cellars especially built for them.

It was the first of December — Christmas was approaching. The men had brought in the evergreen from the forest, for a branch must be tacked above the door of each room and over the big fireplaces, else it would not be Christmas. But no one seemed really to have heart. Every one was triste even to little Marie who sat by herself much and often wished aloud for her papa.

Just a-week-to-Christmas was a gloomy day; the dark shut down early. Martilde, the aged aunt of the seigneuresse, muttered almost a ceaseless prayer as she hugged nearer to the hearth of the open fire. Grandpere Crevier leaned his chin on his cane and kept his eyes closed as if he would shut out the sorrows of the world and little Marie, finding her mother distrait, came to Martha and begged her to sing to her.

Possessing a voice of much sweetness, she had first amused the children with little English songs, but had now become sufficiently familiar with the new language to use it understandingly. Taking the child in her arms, she drew her chair within the warmth of the fire and began that old lullaby, "Roll The Ball," a song that French Canadian mothers and grandmothers in the States will tell you was sung to them by their mothers when they were children, and by other mothers and grandmothers for centuries back:

"Derriere chez nous,

Y tung, Y tang,

En roulant ma boule.

Trois beau canards s'en vont baignant

Rouli, roulant, ma boule roulant,

En roulant ma boule,

"Trois beau canards s'en vont baignant

En roulant ma boule,

Le fils du roi s'en va chassant

Rouli, roulant, ma boule roulant.

En roulant ma boule,

"Le fils du roi s'en va chassant.

En roulant ma boule,

Avee son grand fusil d 'argent,

Rouli, roulant, ma boule roulant

En roulant ma boule,

"Avee son grand fusil d 'argent,

En roulant ma boule,

Tue la noir, blesse la blanc,

Rouli, roulant, ma bouli roulant,

En rouli ma boule, roulant,

En roulant ma boule."

* * *

Once through, and at Marie's request, Martha was beginning again when there was a great shout, as of welcome, outside, and all, hurrying to the kitchen, found the Damoiselle crying and praying over her husband, Sieur Jean Crevier, who looked lean and gaunt but with a very satisfied expression, recounting his escape from the Iroquois and how he had made his way back home aided by a friendly Huron.

Everybody was happy, and Martha, still a prisoner, slipped away and sat by herself in her own room. These friends were kind; she had a comfortable home, but she was alone. If she could only be with those she loved. It was so that Marguerite found her, calling as she came: "Come, Father Louis-Andre is here. It is good news for you. Come." And Martha followed her to hear the story from the good Father's lips:

He had found her little son, John. He had seen him but the week before. He was in the family of M. Argenteuil in Montreal, in their service. He was a fine boy and was growing well; he would be a good man. The others rejoiced with her and Jean and Marguerite promised to take her to Montreal to see him. It was her Christmas as well.

It would seem that only one thing remained to complete the happiness that was Marguerite's at the return of her husband. It was the salvation of Martha's soul that she craved and for which she prayed. Her love for the English captive had grown very great; it was as if Louis had sent her to be his mother's special charge. Sometimes she pleaded with her gently and Father Louis-Andre often urged baptism.

It was nearly three years that Marguerite's prayers were unavailing and then they brought the news that Martha 's young son had been baptised into the faith in the church of Notre Dame on the third of May. Six weeks later in June, 1693, she, too, stood before the altar in the same church and received the sacrament of baptism by the sprinkling of holy water on brow and breast.

That day Father Guyotte wrote on the church record:

"Le lundi vingt neuvieme jour de Juin de I'an mil six, cans quatre vingts treize a ete solennellement batisee sous condition une femme Angloise nommee en son pais Marthe, lequel nom lui a ete conserve au bateme, Laquelle nee a Sacio en la Nouvelle Angleterre le huitieme de Janvier (vieux stile ou 18 nouveau stile) de I'an mil six cens cinquante trois du mariage de Thomas Mills natif d'Excester en la vieille Angleterre et de Marie Wadelo native de Brestol proche Londres et mariee a defunct Jaques Smith Habitant de Barwie en la Nouvelle Angleterre y aiant ete prisele 18 i\Iars de I'an mil six cens quatre vingts dix par ]\Ir. Artel, demeure depuis trois ans au service de Monsieur Crevier a St. Francois. Son Parrein a ete Monsieur Pierre Boucher Ecuyer Sieur de Boucherville, Oificer dans le detachment de la marine, Sa marreine Dame Marie Boucher, veuve de Monsieur de Varennes Gouverneur pour le Eoi des Trois-Rivieres.

Martha Mills

Marie Boucher

E. Guyotte

Boucherville

The godfather was Pierre Boucher, former Governor of Trois-Rivieres and now "ecuyer" and owner of the great fief of Boucherville, opposite Montreal, and he was a brother-in-law of Damoiselle Marguerite. The godmother was his daughter Marie, the widow of De Varennes, also in his time Governor of Trois-Rivieres, the signatures of the noble godfather and honored godmother appearing with Martha's on the record.

But the great joy that filled the heart of Marguerite on the June morning when Martha took upon herself the vows of the church was not to be of long duration. Scarce a month after her return to Saint Francois Marguerite suffered the most cruel blow of her life. Again the Iroquois descended upon the island and carried off her husband who was at work in the fields with some fifteen workmen, and he probably died at Albany from his wounds and suffering involved in his captivity.

* * *

Summer suns and winter snows counted off the years to 16 and Martha Smith lived on in the home of Marguerite Crevier. The long struggle between the French and English for supremacy in the New World still continued, now quiescent, now breaking forth with stinging hatred. But the power of the Iroquois had been broken, the allied tribes found matters of graver importance nearer home to hold their attention, so that savage forays across the Canadian border were becoming less and less, while New England was being more strongly peopled by colonists from the Old World.

In the year 1706 there was a general exchange of prisoners and that year Martha Smith and her son John, now to manhood grown, probably came back to the old home in Berwick, since after that date their names do not appear among those remaining in Canada. Martha must have been sorrowful at the thought of leaving the friends at Saint-Francois, and especially Marguerite whom she had learned to love as a sister; but she must have been stirred by far deeper emotions at the thought of returning to the scenes of her girlhood and married life, to the old home and the old friends.

And John? He was but a young man and quickly found companionship among the friends of his parents. He married the beautiful Elizabeth of Kittery and when experience was added to his years, he was made an elder in the old Congregational church at Berwick. He became a man much esteemed, lived to an honorable age with his family about him and in the faith of his ancestors he was gathered to the fathers.

Author's Notes.

On August 31, 1963, Governor Fletcher of New York writes in a letter that the Iroquois had a prisoner named Mr. Crevier of St. Francois; that they bad torn out his finger-nails and were preparing to burn him at the stake, when Colonel Peter Schuyler, in command of the garrison at Albany bought him for fifty louis d'or and that the poor captive was then very sick in that city. "Jean Crevier," says Suite, "doubtless died at Albany from his wounds and from the suffering he underwent during his captivity among the Iroquois." The next year his eldest son signs as seigneur of Saint-Francois.

The account of Martha Smith's captivity is drawn in great part from her long baptismal entry in the church of Notre-Dame at Montreal and from a scarce pamphlet in French, Suite's "Histoire de Saint-Francois-du-Lac," the latter a critical re-statement of the facts on ancient records concerning the family of Sieur Jean Crevier, in whose household Martha passed so many years; L'Abbe Maurault's "Histoire des Abenakis," the Massachusetts archives and the York County records. The baptismal record is the copy made by C. Alice Baker, deceased, and is now in the hands of Emma L. Coleman of Boston.

The Abenaki reservation is located at Pierreville, Canada, and on land given them by Marguerite Crevier before she died. There is a small chapel and upon an interior wall a tablet to the late U. S. Senator Matthew Stanley Quay of Philadelphia, a descendant of Abenakis. He also gave $5,000 for a library for the mission.

In nearly every New England city where there are French-Canadians of any distinction one finds descendants of the Abenaki Indians through the marriage of Joseph-Louis Gill. The record of the family is a most honorable one.

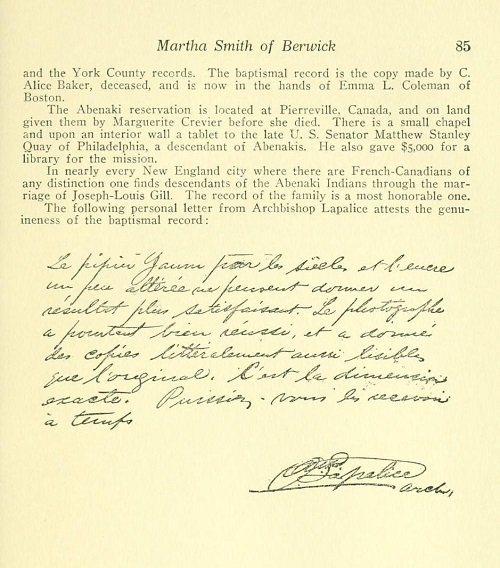

The following personal letter from Archbishop Lapalice attests the genuineness of the baptismal record:

Contributed 2024 Aug 10 by Norma Hass, extracted from 1916 The Trail of the Maine Pioneer, by Maine Federation of Women's Clubs, pages 67-85.

Copyright © 1996- The USGenWeb® Project, MEGenWeb, York County

Design by

Templates in Time

This page was last updated

10/30/2024