Almshouses once served as the primary institutions for the housing

and care of the poor and homeless which included the sick, disabled,

mentally ill as well as unwed mothers, children and the elderly.

In addition to the resident population, the almshouse offered aid to

the transient poor by providing a meal and temporary shelter.

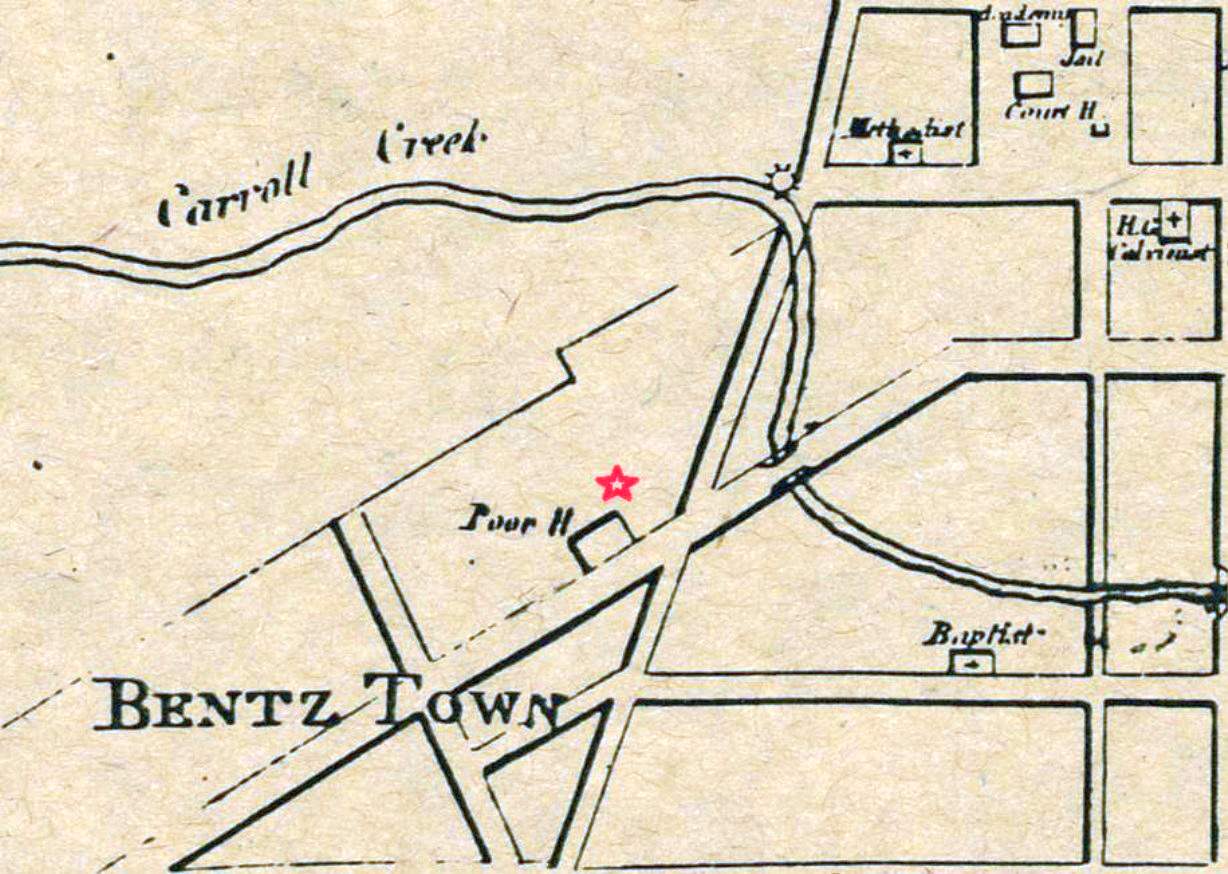

Legislation in Maryland passed in 1768 to establish the first almshouses

in Anne Arundel, Prince George's, Worcester, Frederick and Charles

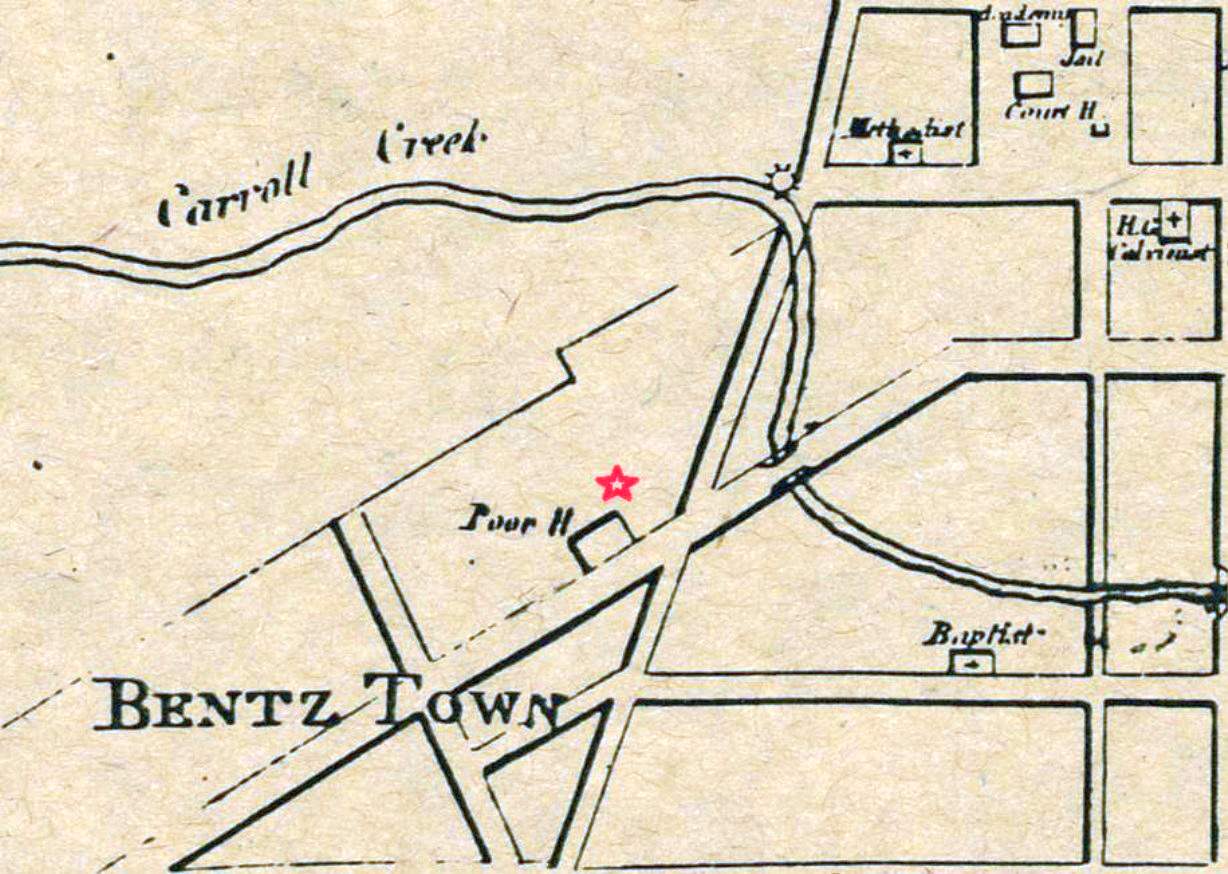

counties. The first "almshouse" in Frederick County was opened about

1770 and was located in the Bentz Town section of Frederick Town on

the north side of West Patrick Street.

Legislation in Maryland passed in 1768 to establish the first almshouses

in Anne Arundel, Prince George's, Worcester, Frederick and Charles

counties. The first "almshouse" in Frederick County was opened about

1770 and was located in the Bentz Town section of Frederick Town on

the north side of West Patrick Street.

In 1786, a fire destroyed, but a new one was soon built in the same vicinity

(today would be 253-259 West Patrick St). It had its own 'Potters Field' burial

ground, but is no longer visible, although the bodies likely remain. Not much

is known about the building, but it is noted on the 1808 Varle map, listed as

"Poor House".

As time progressed, a larger almshouse was needed and, in 1830,

a 94-acre parcel from the family of Elias and Catharine Brunner was

acquired with the stipulation it was to be used for the poor. It was

opened in 1832 with Henry Steiner as overseer and was located two miles

west of the town on the present Rosemont Avenue extension. This new

almshouse was a 3-story brick building with basement and had 36 rooms

and would now have a farm to provide food for the residents and also provide

work as the residents were expected to perform some duties in repayment

of the services they received. It would also have a new 'Potters Field' but

is now usually listed as Montevue Cemetery.

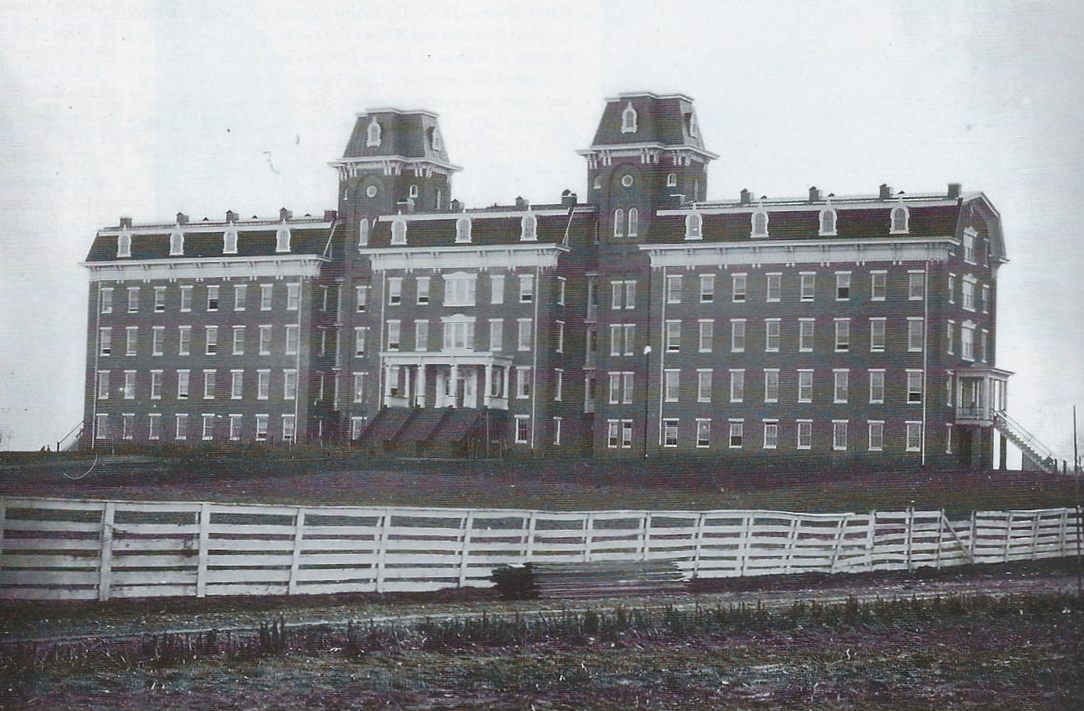

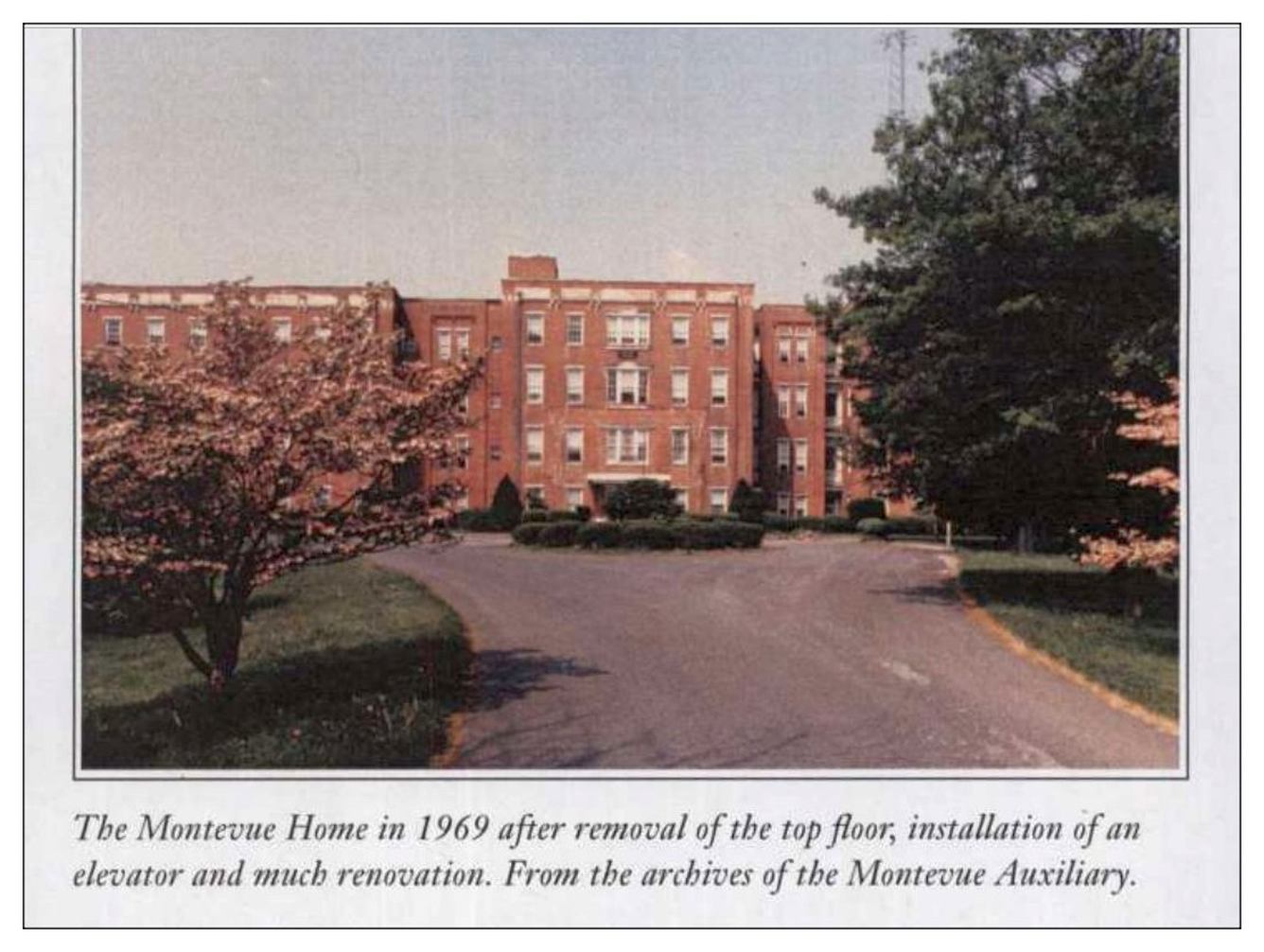

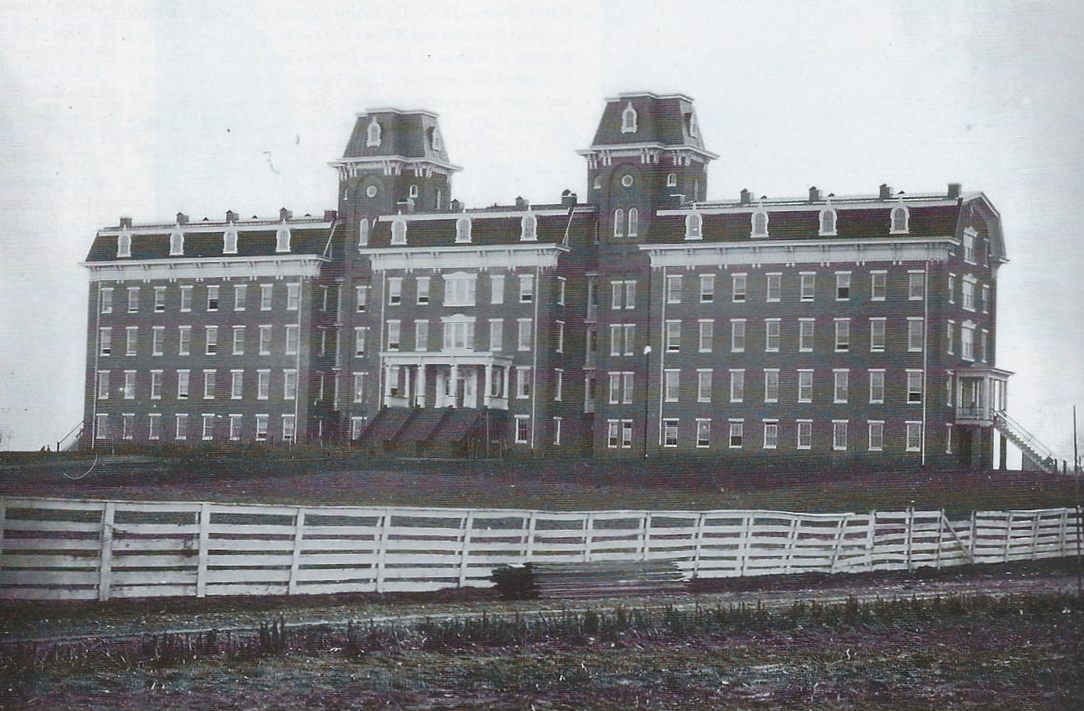

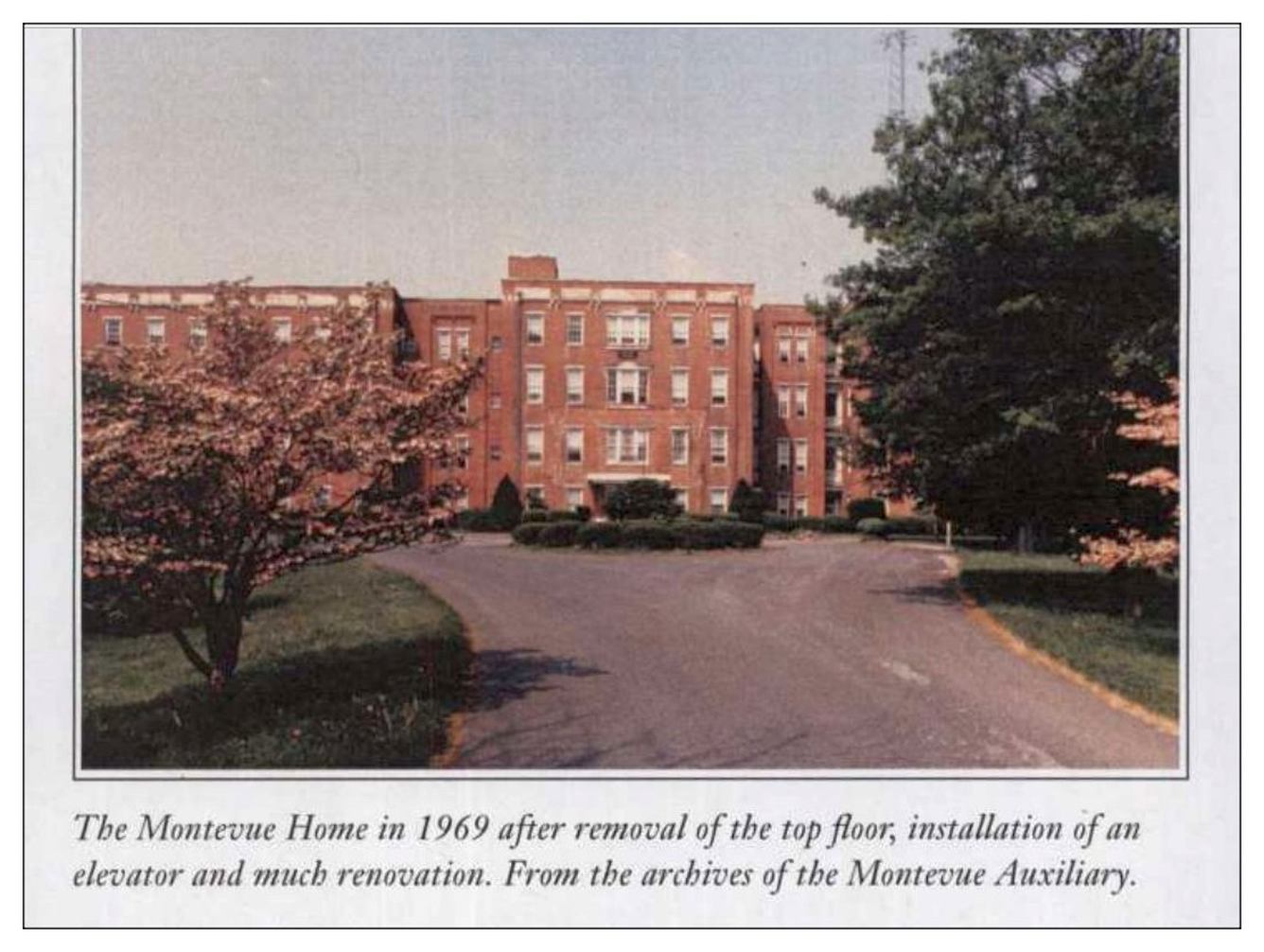

In 1870, once again, larger quarters were needed for the almshouse and

a new, 4 1/2-story brick facility over 100 rooms, an operating room on the

top floor and two residential wings, one for male and one for female

residents, separated from the centre building by towers with passages

connecting the wings. Each floor of the towers had water closets and

bathrooms for the inmates. The new building now had a dining hall

and a second kitchen and was heated by steam.

The new building was named Montevue Hospital.

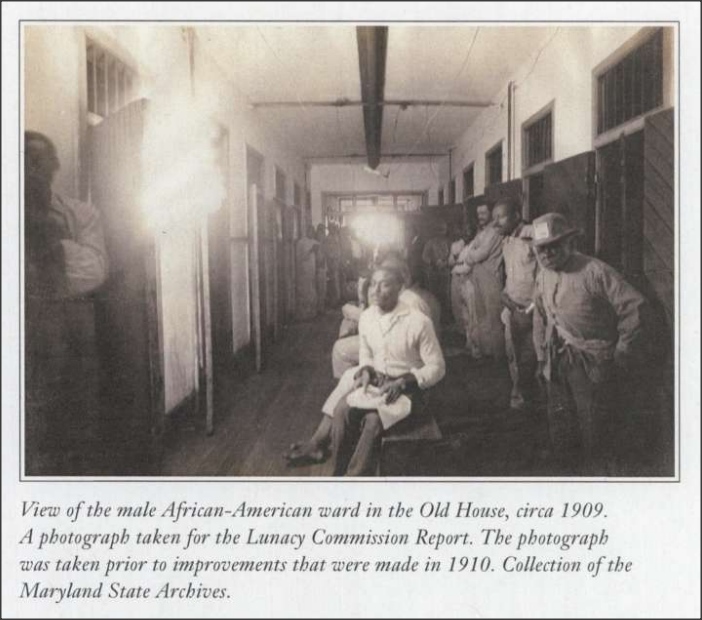

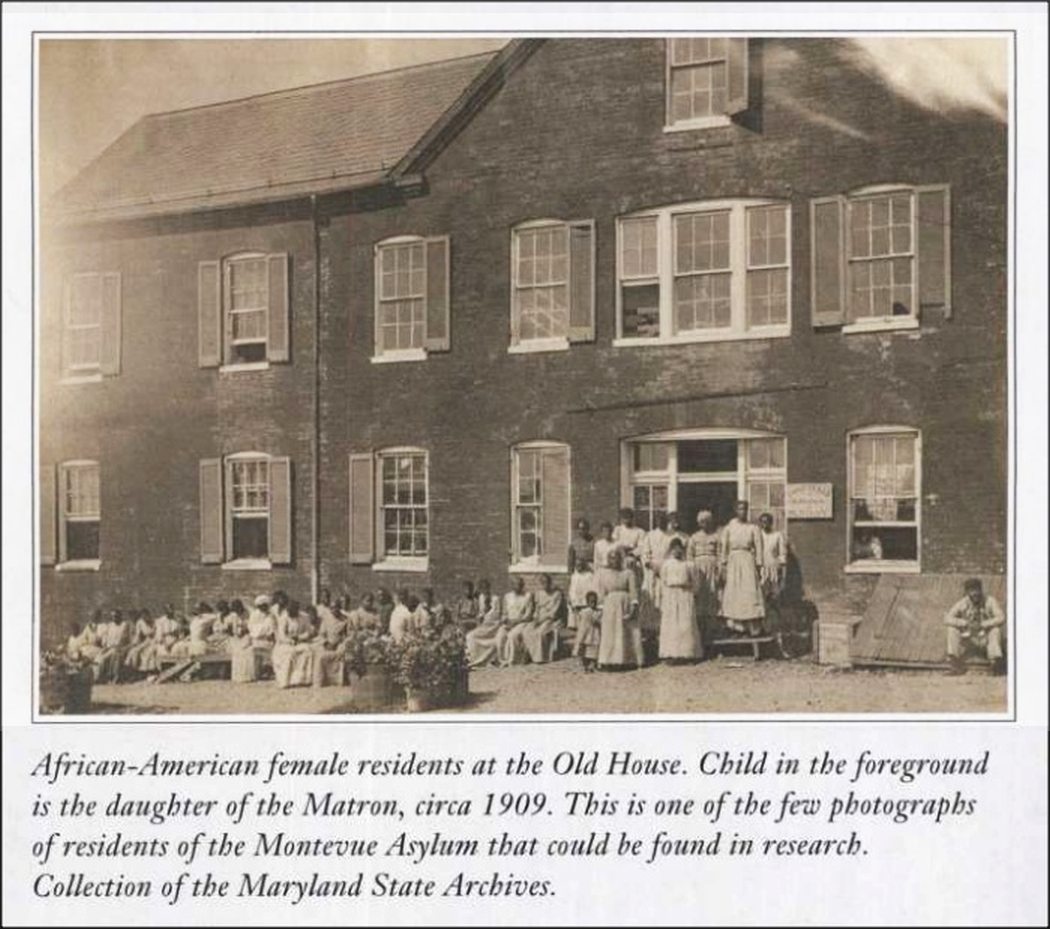

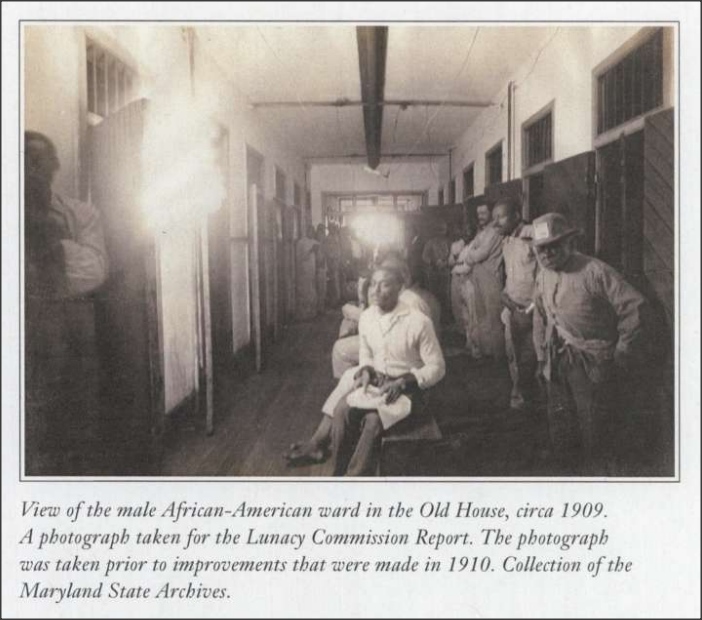

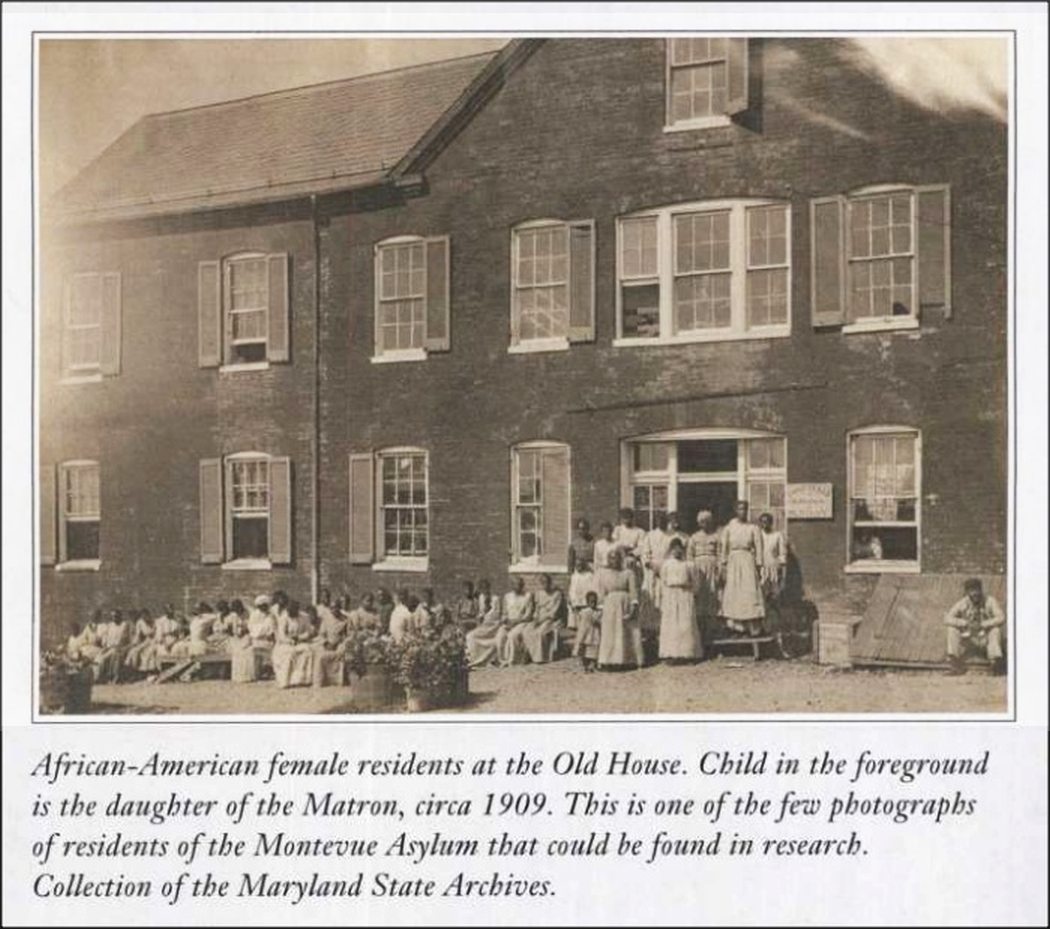

The white residents were moved to the new building, but the colored

residents remained in the 'Old House'.

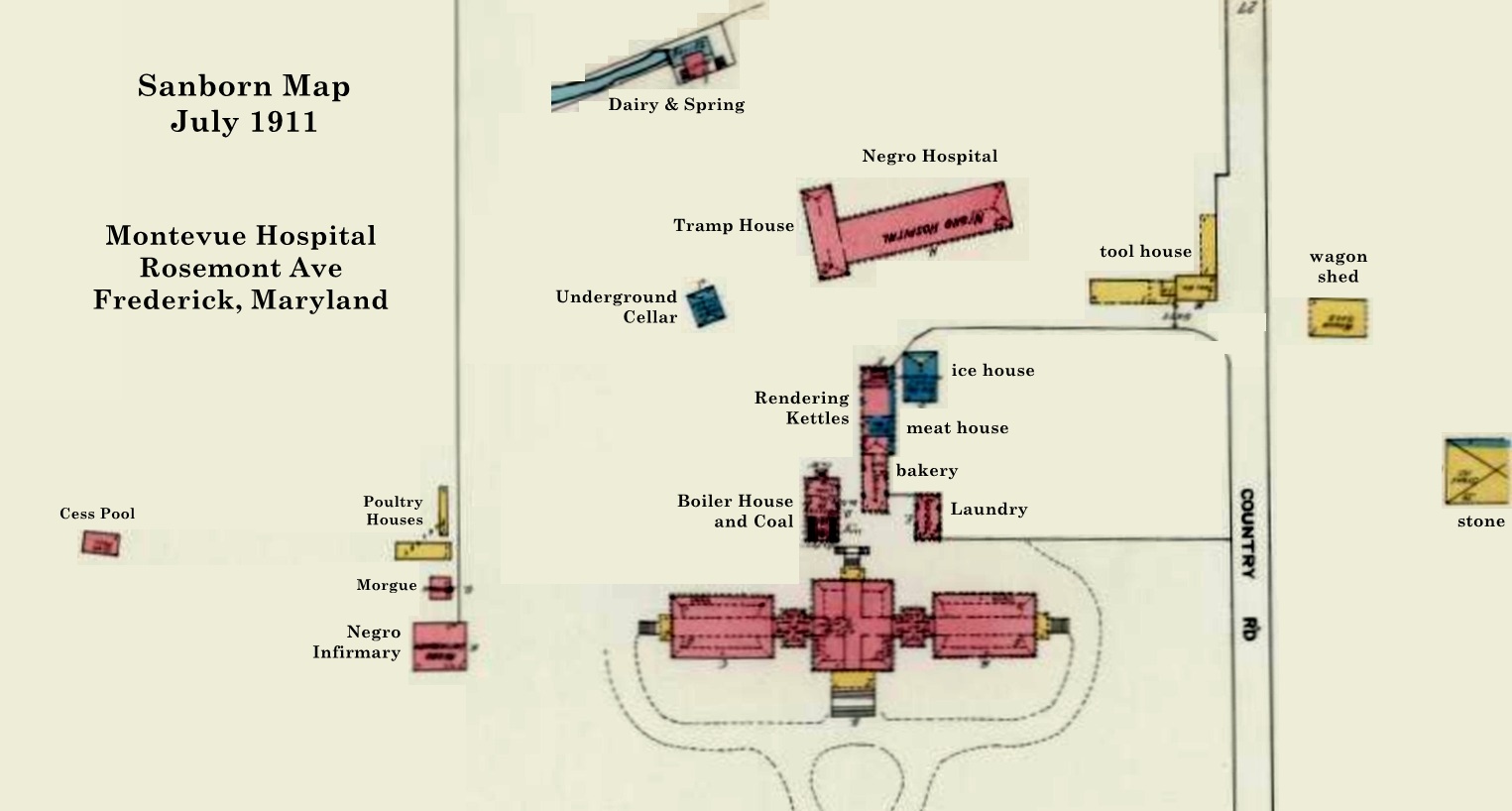

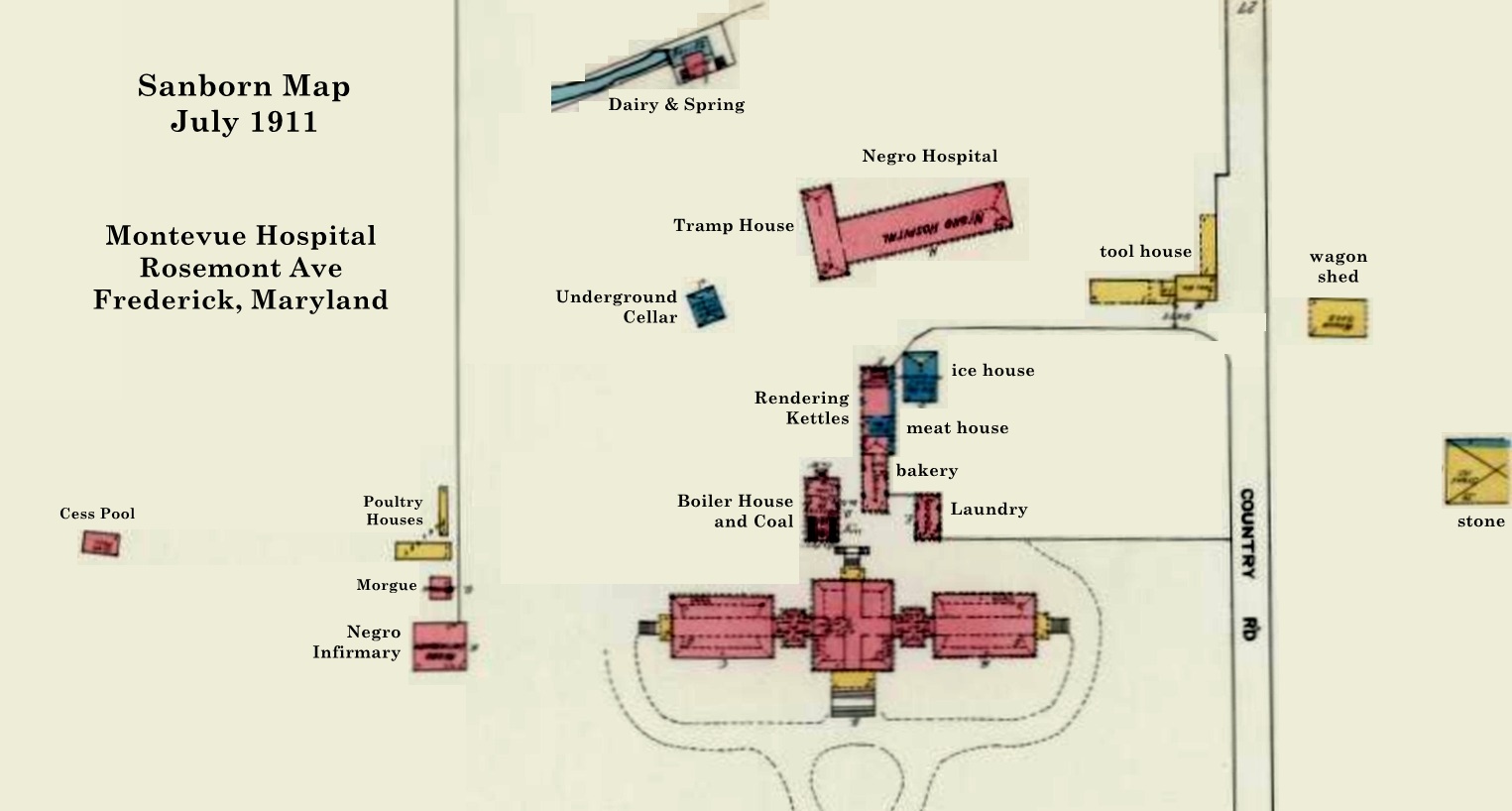

An addition was added to the 'Old House' to house transients, known as

'The Tramp House" and those men were expected to work on the farm

or the paving yard under supervision of the 'Tranp Boss'.

Montevue had the largest record of feeding and lodging tramps.

Between 1876-1877, Montevue served over 8,800 tramps.

In 1877, Montevue Hospital had the second largest resident population

among Maryland’s public almhouses and asylums and included residents

from other counties as well. Additional buildings added were a springhouse

and dairy, laundry, boiler house, barns, sheds and a morgue known as the

'Dead House'.

Pigs, chickens, cattle and dairy cows were raised which

supplied food to the hospital and the county jail.

The Montevue Hospital was known statewide for its large population

of white and African-American mentally ill residents. Providing housing

for the “insane,” was one of the reasons almshouses were deemed

necessary by both state and county governments. From colonial times

through the mid-nineteenth century, there was little if any recognizable

medical treatment for the mentally ill.

In 1877, Maryland’s governor appointed Dr. C. William Chancellor,

Secretary of the State Board of Health, to inspect all almshouses,

prisons, reformatories and public institutions and report on sanitary

conditions, treatment of inmates and the number of inmates statewide.

The Chancellor Report acknowledged the “shocking conditions” found

in most institutions. In some counties, almshouses were little more

than shacks or converted barns.

In the Chancellor report, the design of the Montevue Hospital building

was praised, especially the division of residents by gender, but the

institution was criticized for failing to separate the sane and insane

in the wards of both of the buildings, where white inmates were housed

on upper floors in cells with barred windows.

And the Old House, the home for African-American inmates, also had barred cells

and other

confining features. The report cited Montevue for housing the very sick

with the healthy inmates in both buildings and for overcrowded and dirty

quarters in the Old House. By the mid-1890’s, even a Frederick County

grand jury, which had the responsibility of reviewing the county jail and

home each year, suggested that conditions could be improved for the

African-American residents.

The new building for them was finally

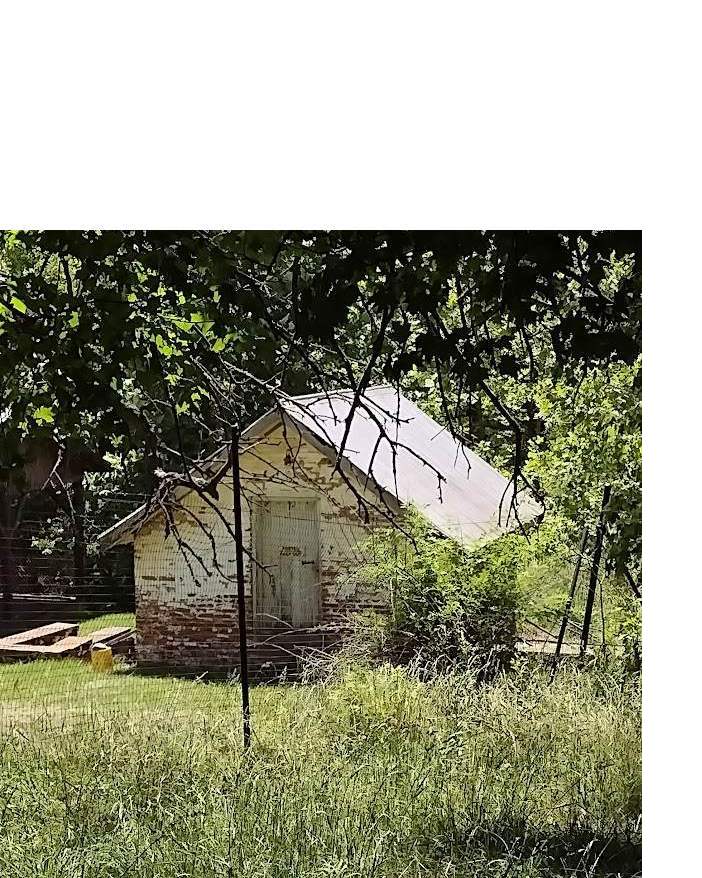

opened in 1897 (this building still survives and is used by Frederick County).

In 1886, legislation was passed prohibiting children from living in almshouses

for more than 90 days unless they were so disabled they couldn't function.

Instead, they were to be placed with "respectable families or institutions".

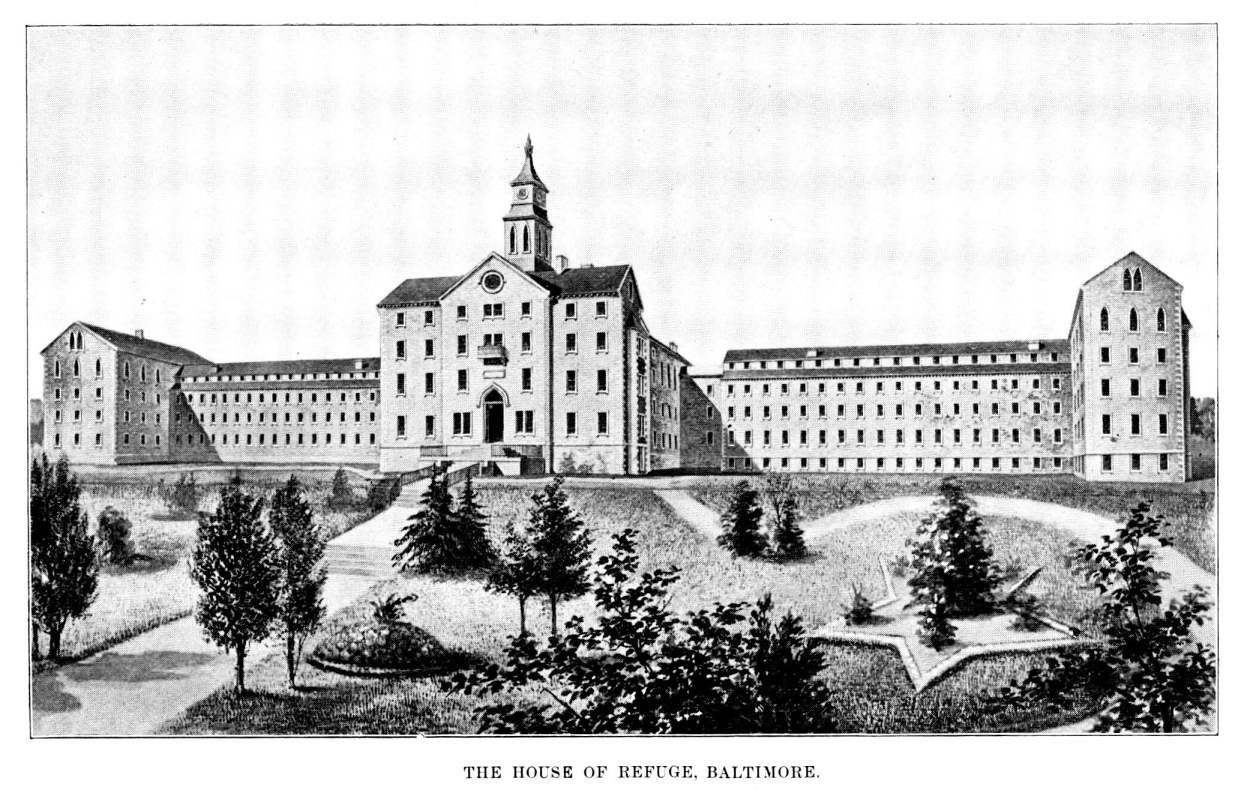

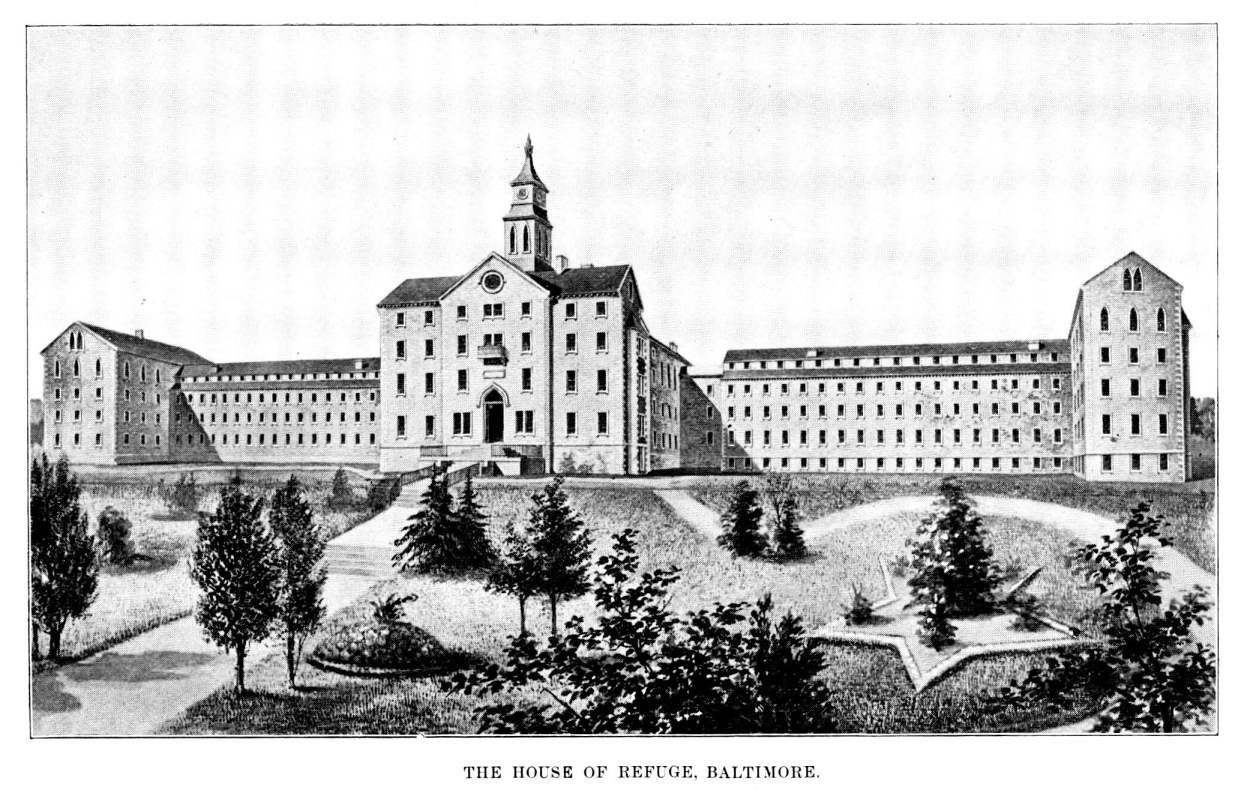

Some of the youth were sent to the House of Refuge, a youth home in western

Baltimore County on the Frederick road.

The Montevue Cemetery (Potter's Field) was located on the south back side

of the hospital. It was estimated there were about 500 burials from 1871

through 1889, but unfortunately complete burial records weren't kept.

An archtectural and geophysical remote sensing investigation, conducted

for the Frederick County Division of Public Works in 2002, estimated the

number of burials to be 1,240 from 1832 through 1956. These burials

included those of executed criminals and others unclaimed or transients.

None of the graves were ever marked.

When Robert Schell was Superintendent (from 1959) , he, along with

Raymond Creager of Thurmont and Carroll Kehne of Frederick, had a

monument made to mark the cemetery and honor those buried there.

Here's a link for a more complete history on

Montevue

Legislation in Maryland passed in 1768 to establish the first almshouses

in Anne Arundel, Prince George's, Worcester, Frederick and Charles

counties. The first "almshouse" in Frederick County was opened about

1770 and was located in the Bentz Town section of Frederick Town on

the north side of West Patrick Street.

Legislation in Maryland passed in 1768 to establish the first almshouses

in Anne Arundel, Prince George's, Worcester, Frederick and Charles

counties. The first "almshouse" in Frederick County was opened about

1770 and was located in the Bentz Town section of Frederick Town on

the north side of West Patrick Street.