...

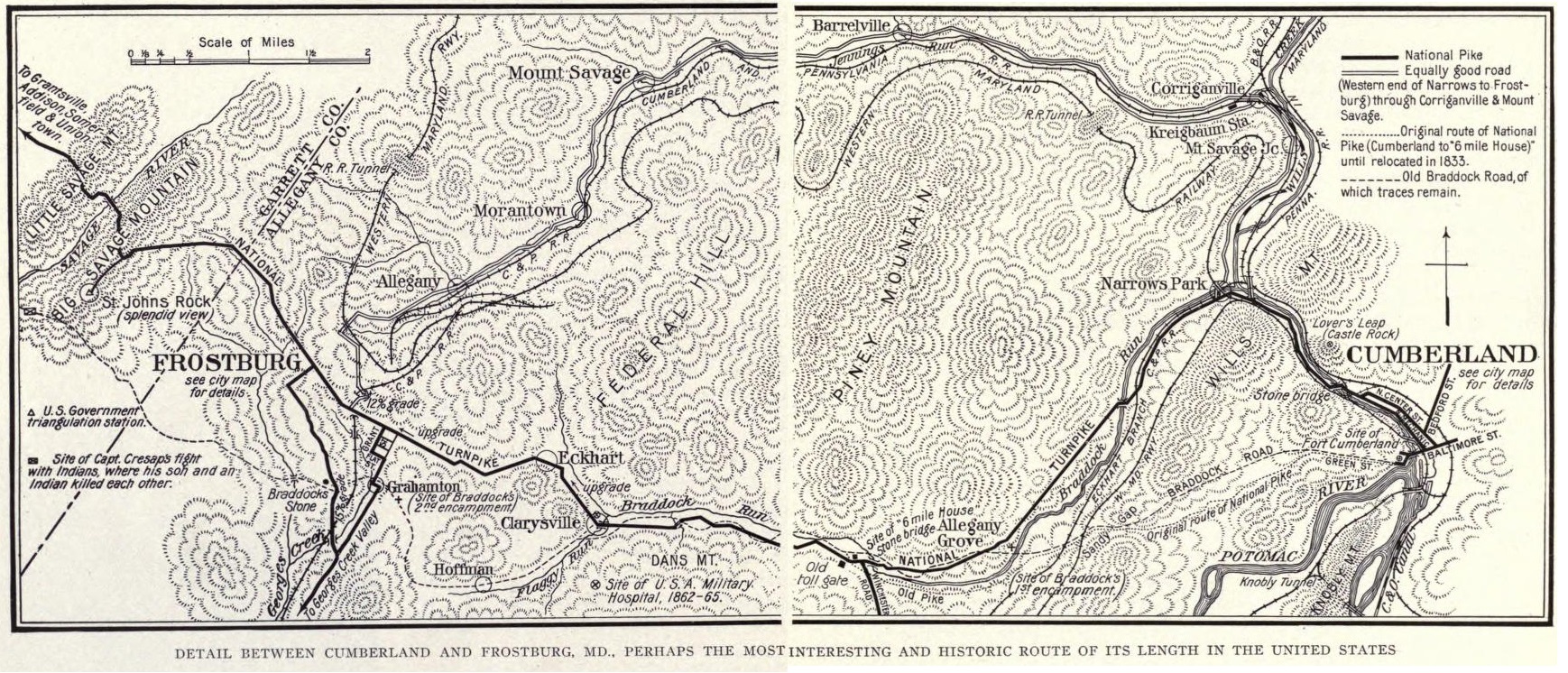

While the highway from west of Hancock to Cumberland is one of the

most winding of its length in the United States, there is absolutely no

chance to lose the way, and the most should be made of the opportunity

for viewing the scenery. As shown by the detail maps on page 29, many of

the various upgrades and downgrades are quite long and steep; but the

curves are mostly wide and the surface fair to good throughout. With the

car in good condition, and carefully driven, there is no danger, though

one should not stop on the curves to view the scenery ; and it is well

also to keep on the lookout for vehicles approaching from the opposite

direction.

Specific description of the different ranges crossed

would be difficult at best ; and the detailed maps show the roadway over

them more graphically than text could possibly do; so the following

paragraphs are purposely condensed. The next range west of Tonoloway,

and the second one beyond Hancock, is known as Sideling Hill, which

reaches an elevation of 1,633 feet just before the principal curve on

the summit. From this point several wonderful views are to be had, not

only eastward across the valley or vast ravine between the two ridges,

but also westward over an apparently endless extension of mountains,

through which Sideling Hill Creek winds its way to the now more-distant

Potomac.

Higher elevations than this will be found on some of

the ridges farther west; but nowhere else on the trip between Baltimore

and Wheeling is there an ascent of 760 feet in a mile and a half, as on

the eastern slope of Sideling Hill, or a descent of 495 feet in a single

mile, as on its western slope. The latter, which starts along a ledge

just beyond the summit, should be coasted (if at all), with the brake on

lightly, not only on account of the grade, but especially to prepare for

the very sharp left curve — almost a "horseshoe" — at the foot. While a

machine beyond control would probably be wrecked on that curve, it

presents no danger to the experienced driver who knows about it in

advance. Naturally, however, the first-time traveler will experience a

sense of relief at being on the easier grades between Sideling Hill and

the next range.

Thomas Cresap, the western Maryland pioneer and

afterward a member of the Ohio Company, is said to have paid an Indian

£25 for widening the original path over this hill, so that white men and

wagons could negotiate it. That was a considerable amount in those days,

and may give some idea of the work involved in the original clearing. In

Fry & Jefferson's map (1755) will be found the name "Side Long Hill,"

from which the present Sideling Hill undoubtedly came.

Even

after this long descent, the downgrade' continues about a mile to Bear

Creek, which is crossed by a stone bridge, followed by a sharp left

curve to the iron bridge across Sideling Hill Creek, just beyond. From

occasional points of vantage on the west side of the creek, in favorable

weather the tourist may look back across the intervening valley, and see

the summit of Sideling Hill, even tracing thereon some of the windings

of the road passed over only a few minutes ago. Such view is likely to

impress one with the courage, as well as the high engineering skill

required to project and construct a through-fare like this across so

great a natural barrier between the Atlantic seaboard and the Ohio

River.

Except for an occasional very small settlement and an infrequent

lonely schoolhouse, this is practically an uninhabited section — wild

and beautiful beyond anticipation, and with a most clear, bracing

atmosphere. The Western Maryland and Baltimore & Ohio Railroads are now

far to the south ; and the only connection of the few inhabitants with

the outside world is by means of this old road, which under the

circumstances is kept up wonderfully well. It seems quite safe to

estimate that there may be more bridges than people from the western

edge of Hancock to the eastern edge of Flintstone.

Even in the

midst of these mountains, whenever the nature of the country admits, the

road straightens out for considerable distances, affording the

experience of running along comparative levels for a half mile or mile,

yielded only when it is necessary to make an ascent or descent. Between

Sideling Hill Creek and the next ridge — Town Hill — there is a great

deal of primitive woodland, and much scrub growth; for part of the way,

also, the road is through red clay and shale. On the left, near a small

bridge and just before a left-handed road, in the midst of this wild

section, is a rough unpainted wood building, with a home-made sign,

"Meals and Lodging"; ordinarily it is not very attractive to the motor

tourist, but might be useful in case of a breakdown in that locality.

There is also a lodging house and country store at Piney Grove, a mile

or so beyond.

Now the road begins the long, winding ascent of

Town Hill which, though it reaches a height a trifle greater than

Sideling Hill, is much more easily crossed ; from the summit there are

the usual fine views, then a long winding descent, with a sharp right

curve part-way down. The valley between Town Hill and the next range —

Green Ridge — is quite narrow; at the foot the road crosses Piney Ridge

Run, a small stream, then starts almost at once up the eastern slope of

Green Ridge. This is crossed at an elevation of only about 1,200 feet;

then one descends a winding road, where careful driving is necessary for

a sharp right — and a particularly sharp left-curve. On the western

slope of this range is a wonderful apple orchard of about 50,000 trees

under scientific cultivation.

There shortly opens up — across the valley of Fifteen-Mile Creek —

one of the most entrancing views on the entire route. In front, above

and below, is a great ravine, extending as far as the eye can see;

straight across to the west are the foothills of Ragged Mountain and

Polish Mountain. Care should be taken for a sharp crossing this summit

(1,372 feet elevation), the descent is shorter and more abrupt, with a

number of turns which should be taken with care; the surface, however,

was almost perfect in the fall of 1914, and the views easily comparable

with the best of those already had. The leisurely tourist leaving

Baltimore in the morning, lunching at Hagerstown and probably intending

to run into Cumberland for the night, is likely to be traveling over

this portion of the old road in the late afternoon; if the sun is

setting bright and strong, the view of its rays coming over the

amphitheater of mountains in the western horizon is beautiful beyond

description.

Caution is particularly necessary in making a very

sharp right turn over a stone culvert spanning a small stream about

two-thirds of the way down the western slope of Polish Mountain ; then

the road is straight ahead, across Town Creek and past the little hamlet

of Gilpin toward the ancient but very interesting village of Flintstone,

which is what might be called the eastern out right and then a sharp

left curve made by the old road in its rather abrupt descent through

very wild country to Fifteen-Mile Creek; this is crossed. -on an iron

bridge, the road just beyond passing over some shorter hills onto a

surprisingly long, level stretch, past a saw-mill on the left. The

saw-mill is at least a sign of human activity so little evident on this

part of the route.

At about the end of this level stretch one

passes, on the right, what remains of an old travern (given as "Pratt"

on the U. S. Geological map, but no town), and begins the ascent of

Polish Mountain, the eastern face of which is quite even and the grade

moderate. But after post of Cumberland. A glance ahead before reaching

the town will show a deep but very narrow gap between Warrior's Mountain

on the left, and Iron Ore Ridge on the right, with Flintstone Creek

flowing peacefully and quietly through. This is known as Warriors' Gap

from the fact that the Indian path, of which there are still traces on

the tops of both ridges, here descended to the level of the present

road.

In his celebrated "Journals," already quoted, Christopher

Gist mentions Warriors' Gap and Flintstone as being "on the way from the

Potomac into Pennsylvania," which proves them to be very old names,

antedating the settlement of this region by the white men. Both are

shown on the map of Western Pennsylvania and Virginia published in 1755,

no doubt largely on the basis of Gist's notes. "Flintstone" was

undoubtedly named from the flint-stones of the Indians, though

confirmation of that point might be difficult to obtain at this late

date.

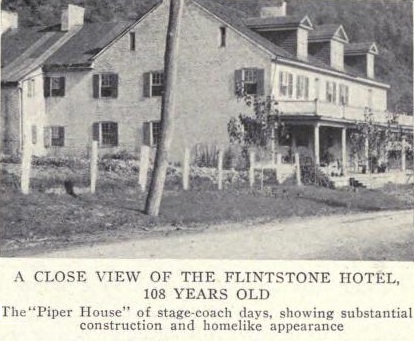

So far on this trip from Baltimore and Hagerstown, the old

taverns and road houses are not as frequent and conspicuous as they will

be found from Cumberland through Uniontown to Wheeling; probably a

larger percentage of them have been torn down or altered. But on the

right-hand side of the road, just before the bridge at Flintstone,

stands the Flintstone Hotel, known as the Piper House in stage-coach

days, still catering in a very modest way to road travel. It was

constructed by the contractor who built that section of the road.

A close view of the Flintstone Hotel, 108 years old. The "Piper

House" of stage-coach days, showing substantial construction and

homelike appearance

A close view of the Flintstone Hotel, 108 years old. The "Piper

House" of stage-coach days, showing substantial construction and

homelike appearance

Making this run in the late fall of 1914,

the writer found that it would be difficult to reach Cumberland on

account of the growing darkness; and, in the mood of taking a chance,

stopped in front of the Flintstone Hotel to ask if overnight

accommodations could be had for three. The proprietor. Dr. A. T. Twigg,

replied : "Yes, so far as we have them." Deciding to stop, the car was

put up, probably in the identical shed that sheltered many a stage-coach

and freight wagon, and we were taken into what was the bar-room of the

hotel in the palmy days, now the doctor's office, where a warm fire

quickly dispelled the chill from the last twenty miles or so over the

mountain roads. A few minutes later we were sitting down to such a good

old-fashioned supper as tradition says this tavern served a century ago;

there was no "grace" said at this first meal — an incident unthought of

then, but subsequently recalled.

It being Sunday, upon

invitation and falling in thoroughly with the custom of the place, we

all attended services at the church on the side of the road which

branches left near the bridge over the creek, guided safely there and

back by a lantern in the hand of Dr. Twigg — for neither electricity nor

gas can be found at Flintstone. Probably few of our friends would have

recognized us in that procession. It was like taking a leaf out of the

past to listen to a genuine old-fashioned sermon, and to such hymns as

were sung in rural New York State and New England forty, fifty or more

years ago. At least one of us instinctively found himself recalling the

almost forgotten words, and making a feeble attempt to join in with the

tune.

Returning to the tavern, we were shown into the

living-room of the family, and while making away with some fine apples,

listened to bits of interesting history, impossible to mention here.

Growing semi-confidential," Dr. Twigg let us know that he was the only

physician in that vicinity, had been there 27 years, and up to that time

had assisted into the world 1,762 little citizens of Flintstone and its

neighborhood — several times as many as reside there at the present

time, for the great temptation, especially to young people, is to leave

their homes in this beautiful mountain region, to be lost in the

industrial maelstrom outside. Probably by the time this article appears

in print, the number "1,762," mentioned by the good doctor, who seems to

be absolutely sure of the exact count, has been materially increased.

Being shown to our rooms by the proprietor, who had almost to be

restrained by force from carrying all of our heavy baggage upstairs,

after the custom of the old-time tavern keeper, we found the rooms

surprisingly large and spacious — at least three times the size of those

in the average modern hotel. Steam heat and running water were

conspicuously absent; but after throwing open the windows to admit an

unlimited amount of the clear, cool mountain air, we dropped into a

sound and wonderfully refreshing sleep, broken only by the call to

prepare for breakfast. At that meal, we discovered that the minister

boarded at the hotel; he was now with us, and of course, we all bowed

our heads for "grace before meat." The minister was one of those

extremely serious young men we sometimes meet ; and a member of the

party "started something" by praising the sermon of the evening before.

Gradually, the conversation broadened to touch upon the subject

of law and order in the mountain villages; and it came out that

Flintstone was a local option village, with nothing in the way of strong

drink to be had nearer than Cumberland. "Then," it was ventured,

"everything must be quiet and orderly." "It would be," replied the

minister, "except that we have no Justice-of-the-Peace nearer than

Cumberland, though if it were easier to get out a warrant, we could stop

some of what goes on." "What might that be?" was inquired. "Well,"

replied the minister, with added seriousness, "some of our people here

once in a while forget themselves, and go swearing up and down the

pike." We thought if that was all the wrong-doing at Flintstone, it must

be quite a model mountain village ; and' at the same time wondered if

some such circumstance as this might not have originated the phrase "up"

or "down the pike."

One who desires to catch something of the

spirit of the ancient highway would do well to stop at Flintstone, and

at some of the taverns on the next section of the route, taking note of

the unpretentious but very comfortable arrangements for old-time

travelers; and if possible talk with older residents, many of whom

personally remember the era of the stage-coach. In the palmy days of the

old road, many famous people stopped at the Piper House, among them

Henry Clay, one of the ablest champions of the project to build the

Cumberland-Wheeling section across the mountains. In fact, the tourist

who wishes to sleep in Henry Clay's room may do so, though the

statesman's initials once carved over the door have disappeared.

At Flintstone the old pike is about 12 air-line miles from the

Potomac River and the two railroads that closely parallel it in the

vicinity of Old Town, the spot where Thomas Cresap, the earliest

permanent settler in Western Maryland, built a home in 1742 or '43. The

little village here in the mountains owes its very existence to the

highway, even mail from points east being carried into Cumberland and

brought out by motor stage. But from now on the pike, the river and the

railroads gradually draw together, until they meet in the city of

Cumberland. Leave Flintstone nearly due west from the stone bridge at

the village center, over a fine level stretch of somewhat more than two

miles to a large stone house on the right, marking the intersection of

the old Hancock Road (or trail) before the present highway was built.

Immediately beyond the stone house begins the winding ascent of

Martin Mountain, the road rising 535 feet in a trifle over a mile; there

are several curves, though none as sharp as those on Sideling Hill, and

the surface is excellent throughout. Over to the left on the way up^ one

catches specially fine views of minor ridges and valleys, with

suggestions of very small villages in the distance. Just beyond the

summit (1,720 feet elevation), there is a comparatively level stretch,

followed by an easy descent of the western face by long stretches of

state highway. If, as is quite likely, the motorist descending any of

these ranges happens to meet a strong four-horse team hauling up a load

of lumber, coal or other heavy materials, he will better appreciate the

grades than being carried over them in a motor car.

At about the

foot of Martin Mountain our road touches the lower edge of Pleasant

Valley, passing on the right "Clover Hill Farm," a well-kept place with

a fine house and large barn. There are no more steep grades on this

section of the trip, as the pike shortly comes along a small stream

which is followed, with several crossings, to the small iron bridge over

Evitt's Creek, at what was Folck's Mill, now Wolfe Mill, as shown on the

detail may page 29. During the Civil War a skirmish took place at this

point, and one Confederate was killed. The old brick and stone mill just

north of this bridge still shows the holes made by Union cannon balls

fired from one of the hilltops nearer Cumberland ; and the large brick

dwelling, still to be seen a short distance farther on, at the junction

of the Baltimore Pike and the cross-over to the Bedford Road, was also

struck and considerably damaged.

Just beyond, there is a

"parting of the ways" for the balance of the trip into Cumberland, both

shown graphically by the detail map, page 29. In the fall of 1914, the

better route was by the first right-turn beyond the small iron bridge,

directly across by an excellent road, cut in part through a hillside, to

its end at the Bedford Road. By taking this route and making a left-turn

in front of a stone farmhouse, the tourist can follow Bedford Street,

mostly brick pavement, straight ahead across the B. & O. R. R. (grade,

dangerous) to the business center of Cumberland, at Center Street, near

the city hall and post office.

The old pike makes no turn beyond

Evitt's Creek, but is direct past the turn-off for the Bedford Road ;

though not in as good condition throughout, it is at least a mile

shorter and, of course, was the route followed by the stage-coach and

freight wagon of long ago. In the not-distant future, it will probably

be made at least as good as the Bedford Street entrance. Following the

old road, one curves around the edge of a minor mountain at the outer

edge of the city, passing a cemetery on the right, to begin at once a

rather long steady descent, from which a good view is had of industrial

Cumberland. From the same point of vantage, the tourist also realizes

why this busy little city in Western Maryland is literally the "Key of

the Mountains"; sometimes it might almost seem impossible to go in or

come out of it by any means except through the air.

But

gradually one catches a glimpse of the wide-sweeping Potomac, pursuing

its peaceful course between the frowning hills of Maryland and West

Virginia; and after a brief but closer study of the topography,

Cumberland is seen to be literally a hub of transportation by road and

rail, as well as the western terminus of the Chesapeake & Ohio Canal,

still a factor in the world's business life. It is also the usual night

stop for a one-day trip west from Baltimore or east from Wheeling, being

approximately half way from each. Hotel and garage accommodations are

fair but not elaborate; the people are generally very courteous and

accommodating to strangers. That city and its unique historic interests,

and especially the choice of roads for the next few miles west, will be

referred to at greater length in the next chapter.

At Cumberland the tourist is about at the beginning of the second half of the Baltimore-Wheeling trip; and in leaving that city for the West, enters upon that part of the Old Pike constructed entirely at the expense of the national government. But no one can afford to pass through this "Key City of the Mountains" without spending at least a few minutes looking around it and learning something of its extraordinary history. Here, at the head of navigation on the Potomac, the travel of the olden days that had come so far by water had to transfer to the land, making its site the most strategic of all between the East and the West. It is situated at the foot of the eastern slope of the Alleghanies, the front door to the famous "Narrows" and the easiest passage of these mountains between New York State and Alabama.

Nowhere else in the entire country can the influence of topography upon the course of history be so clearly traced; and the interest of the trip is much increased by some knowledge of the part this locality has played, especially in the exploration and settlement of the West. By crossing the several ridges between Hancock and Cumberland, the tourist leaves behind the scenes and memories of the war between the States, and enters one of the most important sections traveled and fought over during the French and Indian War, the last between the English and French for supremacy on this continent and, at least in some measure, the forerunner of the Revolution.

We also come into the section-half eastern, half western-traveled and studied most carefully by George Washington throughout the greater part of his life, finding not only evidences of his great faith in the future of the West, but various examples of distinct efforts on his part to develop travel and facilitate the means of transportation across the Alleghanies. In his youth, as surveyor of the lands of Lord Fairfax in the upper Shenandoah, he became personally acquainted with the region beyond the Potomac; this served him well in the subsequent overland trips to Fort Duquesne, while these experiences made him not only the efficient aide of Braddock, but the logical successor to the responsibilities of command when the first campaign against the French at the "Forks of the Ohio" ended in a rout of the English and Colonial forces.

Washington not only traveled the route from Fort Cumberland to the Youghiogheny and Monongahela Rivers, along the general line of the present National Turnpike, but always encouraged, for both commercial and political reasons, every project for connecting the eastern rivers with those of the interior by "portages," predecessors of the highways of a later date. It is a part of the charm of this trip to feel one's self literally following in the footsteps of the "Father of his Country," though his path was often beset with difficulties and dangers; farther along we shall come to the spot where he made his first and only surrender, as a result of the failure of the Virginia expedition of 1754, the year before the defeat of Braddock. It is even a tradition that in the darkest days of the Revolution, more than twenty years afterward, his thoughts were often turned toward the West, as a possible future home for himself and some of his followers in case the Colonies should fail in their struggle for independence.

Further investigation will reveal the fact that Washington suggested the survey of these "western" lands by the Federal Government, which though long under way, is not even yet complete; and had figured with surprising accuracy the saving of distance by this route from tidewater to the Monongahela and Ohio, Fort Duquesne, Presque Isle (Erie, Pa.), Fort Detroit and even to the then little known rivers of the Central West. His interest in the Potomac Co., genesis of the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal, is mentioned elsewhere in this series; in fact, he seems to have anticipated in some degree all that has since been realized in travel and transportation across this section, excepting only the modern developments in steam and electricity.

The outline map on pages 38 and 39 will assist the tourist making the usual quick trip over this route not only to understand the main points about present-day Cumberland, but also to appreciate the strategic advantage of its predecessor, the old fort after which the city was named. In connection with this local diagram, reference should be made to the topographic detail maps pages 29 and 48, showing graphically the succession of ridges, which literally shut in Cumberland from both the East and West. The fairly level spot on which the city is situated was made possible by a sharp bend of the Potomac, which from this point takes a southwesterly course, and is not seen again on this route.

On the West Virginia side, less than two miles away, Knobly Mountain reaches an elevation of 1,115 feet, with higher peaks in the background; and to the north and west, the upper and lower sections of Wills Mountain, almost equally near, rise to heights of from 1,600 to 1,800. After the long descents into the city from the summit of Martin Mountain (1,720 feet), only a few miles east, one may be surprised to learn that Cumberland is itself at an elevation of about 640. The Potomac makes that descent on its way to the sea not only the natural slope but through a series of falls, which the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal overcomes by an elaborate system of locks and dams. This strategic location made Cumberland in the early days the, most important point between the Atlantic seaboard and the Ohio River; and as long as the Potomac was used as part of the overland route to Pittsburgh, it was equally important to and through that city to Lake Erie, though the building of the Philadelphia-Pittsburgh road by Forbes' army in 1759 made a shorter way than the older one through Cumberland.

Here also the two main stems of the Baltimore & Ohio system from the West converge to make one greater line to Washington and Baltimore. Cumberland is a division point for all through business; both passenger and freight traffic are heavy, and practically all the locomotives used are the largest of their respective types. Within the limits of the "Key City of the Mountains," the tracks of this great pioneer railway diverge, as shown by the map page 10 in the opening chapter; no more is seen of the lower one until we reach Wheeling, though we do come into the line of the upper one near Washington, Pa., and follow it the last few miles to the Ohio River. The Western Maryland, a newer railroad, of which the most is seen on this trip in the vicinity of Hancock, parallels the old pike through the Narrows; but at Frostburg it takes the northern course to Connellsville, Pa., and does not again touch our route.

It is worth while before leaving Cumberland to stop a few minutes at the foot of Baltimore Street, near the iron bridge over Wills Creek, and walk along the Western Maryland R. R. tracks to a point a trifle beyond the depot. From there one may see the first dam of the Potomac, near the junction of that river with Wills Creek; the dam is quite unpretentious, but it marks the westerly point of navigation from tidewater, at the very edge of the main Alleghany ridges.

Nearby, also, is the first lock of the Chesapeake & Ohio Canal, now used as a canal feeder only, the boats--still in considerable numbers--being loaded a short distance below, principally with coal from the mines at and around Frostburg. Looking across from the vicinity of the Western Maryland depot, one can see the old part of the city, through which the original line of the pike ran from near the site of Fort Cumberland by the present Green Street to and over Wills Mountain.

Before the railroads came, overland transportation was a serious problem; and water seemed to be the best available and cheapest means. The Potomac was the first thoroughfare of exploration, travel and transportation to the West; but the fact that it could not be used beyond Cumberland added greatly to the amount of traffic over the National Road. At the very first it was proposed merely to make the river navigable; but on account of its many windings, which would make too long a route, a complete canal was found necessary. This then great work was begun in 1828 by Virginia and Maryland, and completed front Georgetown, D. C., to Cumberland, a distance of 184 miles, in 1850, at a cost of about $1 1,000,000. Though once a vital factor in the nation's life, the canal is principally interesting to the tourist of today as a picturesque link with the past. It is now "quiet along the Potomac," except for the whistles of locomotives, the echo of automobile engines, and the subdued bum of industry within the city limits of Cumberland.

Christopher Gist, probably the greatest of the early explorers through this section, George Washington on his first trip to the "Forks of the Ohio," and Braddock on the unsuccessful attempt to drive the French from Fort Duquesne, had already become familiar with the site of Cumberland, opposite which (on the Virginia side), the Ohio Company had erected a store as early as 1750, on lands purchased from Lord Fairfax. But the fort was not erected until 1754-55 when, after Braddock's defeat, which greatly weakened the military prestige of the Colonies, a stronghold was seen to be necessary, not only as a resting place for expeditions to and from the Ohio River, but to guard against the frequent bands of Indians crossing the hills and passing through the forests on sanguinary errands. That fort occupied a bluff on the west side of the city at the junction of the Potomac River and Wills Creek, where the Episcopal Church, a picturesque ivy-covered Gothic structure of brown sandstone, now stands.

It was the real outpost of the Colonies, separated from eastern Maryland by the great barriers of mountains; and almost completely isolated, having no means of communication with the outside world except by primitive roads and the unimproved Potomac River-which gives some idea of the difficulty of long-distance travel a hundred or more years ago. Being on the frontier, never well defined in those days, the ground on which it stood was for a long time claimed by both Virginia and Maryland; but in the end Virginia gave up its claim and the old fort was garrisoned by Maryland troops, though the settlements in both states, as well as those in nearby Pennsylvania, were protected by it.

While the second-and successful-attempt to take Fort Duquesne from the French (1758), was chiefly from Carlisle, through Chambersburg, Bedford and Ligonier, over much of the present Philadelphia-Pittsburgh Pike, Fort Cumberland was again the rendezvous of the Virginia and Maryland forces, which cut a road from here to Raystown (now Bedford) in order to join Forbes' main army, though against the advice of Washington, who preferred to follow the old Braddock Road, with the idea of combining with Forbes much nearer the present site of Pittsburgh. Soon after Fort Duquesne was abandoned, the French power was broken, and the English Colonies opened wide the door into the West; travel and emigration increased rapidly, and Cumberland became, more in peace than in war, an important point in transportation and trade.

The settlement was originally on the west side of Wills Creek, the principal houses being along the present Green Street, which helps to account for the first line of the old pike being laid out that way instead of through the "Narrows." In 1787, when there were only 35 families in the place, the settlers around what had been Fort Cumberland petitioned the legislature to establish a town to be named after the fort, which was done. The first post office was established in an old log cabin on North Mechanic Street in 1795; three years later Allegany County was created and Cumberland made the county seat. It was incorporated in 1815; and grew slowly but surely in population and influence.

The legislation creating the National Pike was very specific in its mention of Cumberland; and this great thoroughfare to the West came to be equally well known as the "Cumberland Road"; this is perhaps the only city in the United States today having an important through highway named for it. On the other hand, the city and section were proud of the road, western Maryland usually sending to Congress men pledged in favor of maintaining it, even after the building of the railroad lessened its relative importance. In the busy days of the pike, Cumberland was naturally the residence of many stage coach and freight wagon drivers, among them Samuel Luman, Ashael Willison, Hanson Willison and Robert Hall, substantial men in the community and honored by those who knew them. While the old drivers and innkeepers have about all passed away, quite a number of people in and about Cumberland remember them very well. Ashael Willison died only about three years ago, though the majority of those who drove on the old road, or kept taverns along it, have been gone much longer.

How great the travel over the National Pike before the building of the B. & 0. R. R. may be estimated from the fact that during the first twenty days of March, 1848, 2,586 passengers were carried through Cumberland in stage coaches. One old-time resident claims to have counted fifty-two six-horse wagons in sight on the road at one time, and to have seen at least 4,000 head of western cattle quartered at a single place. Then came the decline, which carried it to so low a valuation that both Maryland and Pennsylvania took their part of it as a gift, only after large additional sums had been spent by the government in its improvement.

Today Cumberland is the second city in Maryland, and the largest one on our route in the Allegheny Mountains, with a population of about 23,000. It is an important industrial and commercial center, within twelve or fifteen miles of vast coal measures, with inexhaustible supplies of rock and fire clay of excellent quality at its doors. Brick and steel, for which the raw materials are at hand or easily brought by rail, are produced in large quantities. Scientific road building, both by the state and Allegany County, have resulted in fine roads within twelve or fifteen miles of Cumberland, toward Bedford and east and west on the pike, as well as good shale and dirt roads on the West Virginia side of the Potomac, great improvements having been made within the past five years. The city looks prosperous and has a number of substantial buildings, especially banks.

The original ford from South Mechanic Street (a short distance below Baltimore Street) to the west side of Wills Creek passed over a spot subsequently "filled in" to make what is now Riverside Park. While of comparatively recent origin, and of no practical use to the tourist today, a glance at the photograph on page 37, and the easterly part of the local map page 39, may be of interest as helping to identify the original route of the National Road as specified by the United States Commissioners in their Report of December 30, 1806, on the basis of which Congress authorized the beginning of the work. This was "from a stone at the corner of Lot No. 1, near the confluence of Wills Creek and the north branch of the Potomac River"; or, about as closely as the spot can be identified by modern landmarks, at the northwestern corner of the park, about opposite the curve of the trolley tracks.

Actual construction began at this point in May, 1811, proceeding westward along the alignment of the present Green Street to the eastern slope of Wills Mountain, the first ten miles-over the mountain and into the present line of the road past the Six-Mile House (see detail map, page 39)-being completed in September, 1812. It was not until 1833, after the shorter but steeper way had been used for over twenty years, that the start of the National Pike out of Cumberland was re-located to use North Mechanic Street and the longer but much easier route through the "Narrows." Only the latter is known by most present-day travelers, though the former is a vital part of the old re-ad's history.

The usual route west of Cumberland is from Baltimore Street, the basic thoroughfare, out either North Mechanic Street (the actual Pike) or North Center Street, next parallel on the right; both are used extensively and shown in equal detail on the local map, page 39. Near the western edge of the city, North Center makes a short deflection into North Mechanic, the latter crossing at once the Wharf Branch of the Cumberland & Pennsylvania R. R. tracks, at grade, into the famous "Narrows," perhaps the one most interesting topographical feature between Baltimore and Wheeling. Here is found a practically level road along the floor of the gap or gorge, whose average width from the towering heights of the two sections of Wills Mountain is about a half-mile, at the top, sloping to 125 yards at the bottom, and 900 feet deep.

Wills Creek, flowing through the center, is crossed at the eastern end of the narrows by the picturesque and historic stone bridge, of which the photograph on page 36 is a close view of the general structure and solid arches, though the smaller one on this page gives a better idea of the long, sweeping approaches without grades, and the great hills on either side, as well as showing higher water in the Creek. This gorge, which will be quickly identified by anyone who has traveled through it by rail in daylight, provided the National Turnpike with a nearly level entrance into the Alleghanies, and opened the easiest way to and over the main ridges beyond. On the right are the tracks of the B. & O., the building of which did more than anything else to take travel off the old road, and on the left the Western Maryland, the newest transportation line between Cumberland and Pittsburgh.

It is a matter of passing interest that the bridges on the National Road in Maryland, including the one shown in these pictures, were more than once the subject of controversy between that state and the Federal government. When assenting to the change in location from the original line over Wills Mountain to the present one through the Narrows, Maryland made a condition that the part of the road embraced in the change should be constructed of the best materials, upon the macadam plan; that a good, substantial bridge should be built over Wills Creek at the place of crossing, and that stone bridges and culverts should be constructed wherever the same might respectively be necessary along the line of the road.

This was a wise enactment, and as a result, many of these bridges are still as strong and as substantial as the day they were built. Years later, after the road had deteriorated, and Congress had decided to let it lapse back into the control of the several states traversed, Maryland and Pennsylvania accepted their parts only with the provision that the government should put it in good condition within their boundaries. The War Department, of which Lewis Cass was then Secretary, appealed to Congress for an appropriation of $600,000 to make the necessary repairs between Cumberland and Wheeling. Congress cut this down to $300,000, which led the engineers of the War Department to plan a reduction in cost by making some understructures of stone and the superstructures of wood. But this change was refused outright by Maryland, and the government had to yield; so, in the end, the stone bridges were built, after which Maryland took over and has since controlled its portion of this road.

The Old Pike-which, of course, had the first choice for right-of-way--is now, as in the days of the stage coach and freight wagon, the principal gateway to the West, with no alternate passage for many miles above or below. As the view shows, its roadbed is about as substantial as either of the two railways alongside. Years ago the George's Creek & Cumberland R. R. was built as a short road to connect the mines of the American Coal Co., in the George's Creek district, and certain allied interests, with the main line of the Baltimore & Ohio, and the Pennsylvania R. R. in Maryland (short connecting link from Cumberland to the main line of the Pennsylvania system at Huntington and Altoona, Pa.); and being comparatively early in the field, was able to pick out and utilize part of this favorable route through the Narrows, on the opposite side of the Pike from the B. & 0. In the course of time this right-of-way became exceedingly valuable, and when the Western Maryland R. R. desired to head off from Cumberland toward Connellsville and Pittsburgh, the strategic location of the George's Creek & Cumberland led to its purchase at a substantial figure, to become almost a necessary part of the new trunk line.

On the right, almost opposite the old stone building now used as a storehouse by the Standard Oil Co., is a prominent escarpment about 1,000 feet high, known as "Lover's Leap," from which an Indian, disappointed in love, is said to have thrown himself to the bottom of the gorge. It is not recorded that this helped him to any great extent; if he had pushed the other fellow over this cliff it might have been more practical, and incidentally, more Indian. The view of the Narrows (almost a mile long) and the surrounding country from this eminence is one of the finest in Western Maryland. The great, narrow defile, or "canyon," as it would be called in the Far West, now cuts the upper and lower sections of Wills Mountain in two, and the old Pike continues through the Gap with scarcely a change in grade, past large sandstone boulders on either side, apparently threatening those who pass beneath, but in reality solid from one century to another.

At the western edge of the Narrows, the old Pike passes first under the Pennsylvania R. R. in Maryland and then under the Western Maryland R. R.; immediately beyond the latter, it makes a decided left turn-away from Wills Creek and alongside Braddock Run (southwest fork of the Creek)-following same past Narrows Park and Lavale to Allegany Grove Camp Meeting Ground, the site of Braddock's first encampment, situated in a narrow valley between the lower section of Wills Mountain (on the left) and Piney Mountain (on the right). From this point the tourist may with advantage glance back toward Cumberland, and with the aid of the map, pages 38 and 39, secure a better idea of the past and present road situation over these few miles than is possible elsewhere.

At a date not entirely clear, Col. Thomas Cresap, the first permanent settler in Western Maryland, advance agent of and member of the Ohio Co. hired a friendly and honest Delaware Indian, Nemacolin, to make a way for foot travelers and pack-horses across the mountains and through the forests from Cumberland to the first point on the Monongahela, from whence navigation, impossible beyond the Potomac, could be resumed for Pittsburgh, Wheeling and the West. The dotted line across Wills Mountain on the map, pages 38 and 39, represents the route probably traveled by Nemacolin, and not long afterward by Christopher Gist, a pathfinder and explorer for the Ohio Co., in 1751-52. In his Journals, Gist mentions a gap (probably between Dan's and Piney Mountains) "between high mountains about 6 miles out" and "directly on the way to the Monongahela"; he also speaks of the roundabout trading path, which at that time he considered an inferior way. After Gist's return from his two trips of exploration, he and Col. Cresap employed Indians to open a primitive road over Nemacolin's trail; and this might be called the actual beginning of the present National Pike.

On November 14, 1753, George Washington, then a young Virginia lieutenant, reached the present site of Cumberland with a message from Governor Dinwiddie of that colony to the French who had come down from Quebec by the St. Lawrence River and Lake Erie to build a fort at the forks of the Ohio, where Pittsburgh now stands. Washington went immediately to Gist's house and fortunately secured that veteran woodsman as companion on the perilous journey, which was undoubtedly made over Wills Mountain instead of through the Narrows; a few weeks later they returned with an unsatisfactory reply from the commander at Fort Duquesne, and the French and Indian War followed. This added new importance to the route, for at least during 1755 it was more a military highway than one of trade and peaceful expansion toward the West.

Braddock's army, in which were both Washington and Gist, started west over Wills Mountain, but so great difficulties were encountered that the general reconnoitered the locality, and in Three days opened the easier way through the Narrows of Wills Creek, by which troops and supplies were afterwards transported. It is somewhat curious that after Braddock's experience, the government engineers should in 1811 have first laid out the National Turnpike over the mountain at a low point known as Sandy Gap, instead of through the Narrows, as was done in the re-location of the first six miles in 1833. These two routes once forked a few rods west of the Six-Mile House, but traces of the older one have now nearly disappeared.

The old tavern known as the Six-Mile House ("Gwynne's" in pioneer days) was burned down several years ago, and the building erected in its stead is an unpretentious private house; its site can be identified by, the mileage, and also by the good road branching left nearly opposite (toward the village of Cresaptown, Md.) This is known locally as the "Winchester Road," running through Cresaptown to a connection with the road south from Cumberland on the east side of Knobly Mountain. It is a very old route, known as early as Braddock's expedition, and is considerably used nowadays by motorists traveling from Frostburg and vicinity through Alaska (Frankfort) to the South Branch of the Potomac, without going through Cumberland.

South Branch is very popular with campers and fishermen during the warm weather, its many cottages and bungalows being occupied by people from Western Maryland and elsewhere. The South Branch of the Potomac is a very beautiful river; many fine black bass are caught there, and a great many innocent angle worms meet a watery grave. It must also have been a popular resort with the Indians, for arrowheads and spears are still found in the surrounding fields.

Beyond the branching off of the "Winchester Road" one looks up the gorge of the Braddock Run straight ahead into the mountain, and there is a renewed consciousness of speeding toward the West. On the left, a short distance beyond, is the old toll-house, location shown on the map on page 39, the only one of its type now standing on this route in Maryland. The old posts, once a part of this toll-gate, were removed from their original places and can now be seen in the low retaining wall at the back basement entrance to the Court House in Cumberland, about 20 feet from the building. They are four-sided iron posts about nine or ten feet high; both are in a good state of preservation, rather imposing, and interesting relics of former days.

Toll House, between 6 & 7 miles west of Cumberland

and Mr. Cady, the last keeper to collect tolls

By this time the tourist will begin

to see more of these old iron mile-posts, though quite a number of the

originally complete series have disappeared. Continue on the good road with

trolley mostly along the Eckhart Branch of the Cumberland & Pennsylvania R. R.,

passing, on the left, the Cumberland & Westernport power house and trolley

barns, to the three corners at the scattered village of Clarysville. This is

easily identified by the illustration on this page of the old Clarysville Hotel,

one of the best preserved on this part of the route, and once considered a

"large and commodious" tavern.

It is said to have been built about 1810

or 1812 by Gerard Clary, who came from Baltimore County, Maryland, and married a

Miss Waddell, whose father owned a tract of land at or near Allegheny called

"Waddell's Fancy." I f it was built as early as that, it may have been

originally on the older Braddock Road, just where it turned from Braddock Run to

go up Flaggy Run toward Hoffman Hollow, through which it climbed to the top of

the ridges south of Grahamton and Frostburg. The relative location of most of

these is shown on the detail map, page 38; Flaggy Run heads at Vale Summit, a

short distance below that map, but a branch of it comes down through Hoffman.

Clary conducted this tavern during part of the old Pike days.

Here, from

the second year of the war between the states to its end, was located one of the

most important U. S. A. hospitals for convalescent soldiers, with the several

frame buildings grouped largely around, though principally in front of the

hotel, as shown in the illustration, page 46. The first building to the right of

the tavern was the dispensary the name of which can be seen on the original

photograph, though almost lost in the reproduction. To the right of the

dispensary was the guard house, a small stone building, the bottom floor of

which was used as a dead house. The building to the left of the tavern, with the

horse and buggy in front, was the residence of Dr. J. B. Lewis, Surgeon, U. S.

Volunteers, in charge of the hospital.

On the opposite side of the Pike

from the tavern a horse will be noticed, tied to the railing. The horse belonged

to Dr. M. M. Townsend, a practicing physician who had charge of several of the

wards until the close of the war. Officers' quarters, the dining room and office

were in the old tavern; the long frame buildings, about 100 feet by 18 feet,

were sick wards, each having two rows of iron cots, with an aisle down the

center. After the war all these temporary structures were torn down and sold,

the iron bedsteads being bought and used quite generally throughout that part of

the country.

Though the picture is generally true to life, the artist

erred badly in putting a wood-burning stack on an engine used in the heart of

the coal regions, and also in showing hard-coal cars on a railway hauling only

soft coal, but the old passenger coach is a faithful reproduction. It was

painted red, had two hand-brakes at one end and one at the other; it was run by

gravity from Eckhart, the next town on our route, to the Narrows, west of

Cumberland, and only coupled on to the coal train to be hauled into that city.

G. G. Townsend, son of Dr. M. M. Townsend, and now of Frostburg, traveled on

this railroad for four years while attending the Allegany Co. Academy at

Cumberland, and was often allowed to "run the car," especially near election

time, when the conductor was inclined to talk politics with the passengers.

After the coming of the trolley, the old car served some time as a caboose and

was then dispensed with.

In looking up data concerning the war-time

hospital at Clarysville, the writer discovered that the first suggestion to

locate it there was made by Mrs. Mary E. Townsend. Though in her 83rd year, Mrs.

Townsend wrote from Frostburg in January, 1915, clearly in her own handwriting,

the following account of how the hospital came to be located there:

"I remember perfectly the first time I went to Cumberland to see my

husband after he went into the hospital there. It was in Dr. George B.

Sukely's room, and he said to my husband: 'Can't you think of some place

near here where these convalescent men, who are not improving in this

dreadful heat, could be transferred?' I did not wait for my husband to

reply, but said I knew of the very place, eight and one-half miles from

Cumberland, in a delightful valley I came through this afternoon-the

finest spring water, a large wagon tavern, several houses and three

large barns not used for years. I went on to describe it as surrounded

by woods, with rocks to sit on, and the air delightfully cool.

"I remember perfectly the first time I went to Cumberland to see my

husband after he went into the hospital there. It was in Dr. George B.

Sukely's room, and he said to my husband: 'Can't you think of some place

near here where these convalescent men, who are not improving in this

dreadful heat, could be transferred?' I did not wait for my husband to

reply, but said I knew of the very place, eight and one-half miles from

Cumberland, in a delightful valley I came through this afternoon-the

finest spring water, a large wagon tavern, several houses and three

large barns not used for years. I went on to describe it as surrounded

by woods, with rocks to sit on, and the air delightfully cool.

"It took Dr. Sukely's idea at once, and he proposed going to see it,

which he did, and found it just the thing. The next day the barns were

cleaned and fresh hay, put on the floor: then the men were taken up in

their blankets and laid on the floor. Many said they had never slept so

well; it proved an ideal spot and hundreds of men were saved by the easy

transfer. The 1,100 feet greater elevation and the pure water made a

great difference.

"My husband, Dr. M. M. Townsend, had charge of

it at first, and everything possible was done for the comfort of the

men; but it was found that an army officer must be employed to take

charge of the hospital. Dr. Townsend was not willing to go into the

army, and Dr. J. B. Lewis, who brought his wife, three children and his

mother-in-law, was employed. Eight government wards were erected, the

few houses fitted up and physicians employed. Dr. Lewis' family and

myself were all interested in the convalescent men and did what we could

for their comfort; at one time there were over 2,000 in the hospital."

At Clarysville the National Pike, which follows the older Braddock

Road most of the way from Allegany Grove, leaves that route (which kept

more nearly straight west through Hoffman, as shown by the map page 38)

by turning right across a fairly long stone bridge. Immediately beyond

it begins a considerable ascent, with a left curve below the Eckhart

mines, crossing the Cumberland & Pennsylvania tracks into Eckhart, whose

most conspicuous landmarks are the mining operations of the

Consolidation Coal Co. We are now entering one of the most interesting

bituminous coal producing sections of the United States; in fact, one of

the very first mines of the now celebrated George's Creek coal was at

Eckhart.

In the earliest days, the coal was hauled by wagon to

Cumberland, where it was put onto flat-boats and keel-boats, to be sent

in time of high water down the winding Potomac to Georgetown (D. C.).

There it was unloaded and the flat-boats broken up to sell for lumber,

though some of the keel-boats were brought back and loaded again. This

was before the Chesapeake & Ohio Canal was built, and one has only to

note again the many windings of the Potomac, as shown on the map top of

page 9, to realize the difficulty of getting coal to market with such

primitive means of transportation.

At Mount Savage, on

the upper one of the two roads between Cumberland and Frostburg (see map

page 48), were rolled the first railroad rails in the United States, in

cross-section resembling an inverted U. Some of these were used on the

Eckhart R. R., and old-timers say that they could tell by the different

sound the moment the car struck them. At that time Mount Savage was a

Promising industrial center, operating two large blast furnaces and

quite large rolling mills. It now has large fire brick and enameled

brick works.

Beyond Eckhart the Pike continues on a fairly steady

ascent, along with the trolley, past the Eckhart Farm, with many fine

views, especially over to the left and back toward Cumberland, into

Union Street, the main street of Frostburg. Entering the town, there is

a comfortable stretch of brick followed by a rather steep upgrade on

rough stone pavement, to the business center at Broadway, an

intersection easily identified by the First National Bank and the

Citizens National Bank on opposite left-hand corners. Just beyond -see

map, page 48-is the Gladstone Hotel, on the right, and a little farther

along the Post Office.

Frostburg is a substantial,

prosperous-looking place, with a population of about 8,000 within the

corporate limits, and from 10,000 to 12,000 within a one-mile radius. It

is situated on top of the divide between the waters of Jennings Run on

the north and George's Creek on the south, that ridge connecting the

base of Dan Mountain on the southeast with that of Big Savage Mountain

on the northwest. Rain falling on the right, or north, side of Union or

Main Street finds its way into Jennings Run, and thence to Wills Creek

and the Potomac at Cumberland; water from the south side of Union or

Main Street runs into George's Creek, and reaches the Potomac at

Piedmont, W. Va. Frostburg has an elevation of 2,100 feet, pure mountain

spring water, magnificent mountain scenery in all directions, a fine

summer climate, and many miles of good road.

From Cumberland to

Frostburg by the National Road is only eleven miles, and about the same

by the State Aid Road, also shown on the map page 48, through

Corriganville and Mount Savage, though by the Western Maryland R. R. the

distance is fifteen miles. It is worthy of note that many of the

principal towns between Cumberland and Wheeling grew up along the old

Pike about twelve miles apart. The two leading taverns in Frostburg at

the height of popularity of the road were the "Franklin House" and

"Highland Hall," the locations of both of which are shown on the local

map page 48. The "Franklin House" site is now occupied by the First

National Bank, on the south side of Union Street and the cast side of

Broadway. "Highland Hall" stood about 'where the Roman Catholic rectory

now stands, and was one of the most popular arid noted taverns along the

road.

The once sharp competition between the regular freight and

passenger traffic lines naturally brought rival ones into existence.

Searight's History of the "Old Pike" mentions the Franklin House and

Highland Hall, but not the McCulloh House, though the latter was

conducted as a tavern much later than either of the others. This stood

on the south side of the Pike, almost facing the road leading from Union

Street to the C ' & P. depot and Mount Savage; it was a large, two-story

brick building, with a broad porch on its front and east sides, the one

on the cast overlooking the large stage and wagon yard that extended

back to the barn where the stage horses were kept. Teams were changed

here and elsewhere about every twelve miles along the route. The

remodeled building is now used as a general store, owned by Shaffer

Bros.

The vast tonnage of this region finds its way, especially to

tidewater markets, through several channels, largely at first over the

Cumberland & Pennsylvania R. R., which, with the Consolidation Coal Co.,

a subsidiary of the B. & O., passes through almost a continuous town in

the George's Creek valley from Frostburg to Lonaconing, connecting with

the parent system both at Mount Savage junction above, and at Piedmont

below. Frostburg is the highest town in the district; then, farther

south, on lower elevations, are Borden Shaft, Midland and Ocean to

Lonaconing, about at the center of the mining region and headquarters

for several of the producing companies, situated in the valley 225 feet

below the George's Creek Big Vein.

Mount Savage junction (see map

above), where the B. & 0. R. R. turns the corner for Connellsville and

Pittsburgh, is a great transfer point for coal, cast and north. Not only

does the Cumberland & Pennsylvania bring a heavy tonnage to that point

from the full length of the George's Creek valley, but it also makes

connections with the Pennsylvania system from its junction with that

railroad at Ellersie, Md., just north of Corriganville and on the Mason

and Dixon line. The George's Creek & Cumberland, running between

Cumberland and Lonaconing, without going through Frostburg, is now a

part of the Western Maryland system, and delivers its tonnage to that

road at Cumberland.

Considerable of the coal mined in this

district still goes to Cumberland and then down the Potomac by the

Chesapeake & Ohio Canal, now controlled by the B. & 0. Boats carrying

about 110 tons each make the trip from Cumberland to Georgetown, D. C.,

or Alexandria, Va., in from four to five days over the water route, in

which Washington was so much interested both before and after the

Revolution. In the very early days some of the coal from this district

was hauled south to Westernport and thence boated along the north branch

of the Potomac, but that is done no more.

In and around Frostburg

are many points of interest if the tourist has time to look them up.

From Dan Rock, on the summit of Dan Mountain (named for Daniel Cresap,

son of the pioneer, Col. Thomas Cresap), about seven miles southeast of

Frostburg, is bad one of the finest views in the Appalachians, embracing

parts of Maryland, Pennsylvania and West Virginia, and an especially

long stretch of the north branch of the Potomac. It is, however,

difficult to reach by motor, though sooner or later the county or state

will probably build a good road to that point.

One of the two

Maryland State normal schools is located at Frostburg, and also the

Miners' Hospital, built and maintained in co-operation between the

state, city and mining companies. The hospital stands on an elevation

overlooking the Jennings valley, by which the upper one of the two

routes from Cumberland enters Frostburg, and commands a magnificent

view. Both this and the State Normal School are located on the map, page

48, which also shows how the connecting route down the George's Creek

valley leaves Union Street by Grant Street, at the eastern end of

Frostburg.

Resuming the trip, leave Frostburg northwest on Union

Street, up a slight grade and over a short stretch of brick, coming

again onto the macadam of the old Pike. There is now an unexpected but

rather steep downgrade, in the course of which the car used in taking

these notes passed a four-horse team laboring slowly up with a wagon of

heavy logs, apparently as was done three-quarters of a century ago.

After crossing the small stream at the foot, one begins the ascent,

which is not ended until the summit of one of the main Allegheny ridges

is reached at Big Savage Mountain.

Midway of this ascent the view

on this page was taken; on the south side of the road and just west of

the two iron posts, where the two men are standing, is the site of the

second brick toll house west of Cumberland. The Boundary line between

Allegany and Garrett Counties as shown on the map, page 48, passes just

west of where that old toll house stood, though a more recent survey of

the boundary line between the counties passes about half a mile west of

that point. Garrett County was made from the western portion of Allegany

in 1872, and the two have since then had considerable trouble over the

dividing line, which is supposed to be from the mouth of the Savage

River at its junction with the Potomac, near Piedmont, W. Va., by a

straight line along the backbone of Big Savage Mountain to the Mason and

Dixon line, at the southern border of Somerset County, Pa.

In

ascending the long steady grade on the eastern slope of Big Savage

Mountain, a wonderful view unfolds over to the left; and it will repay

the tourist to watch for the road built by private subscription, just at

the crest leading to St. John's Rock. This is shown as a spur from the

old Pike on the map, page 38; the "rock" has an elevation of 2,930 feet,

or 50 feet above the point where the main road crosses the summit of Big

Savage Mountain. From the rock, and to a large degree also from the

Pike, one may look back and see Wills Mountain, the Narrows, Sandy Gap,

Dan's Mountain and Frostburg.

Up to the time that a road is

constructed to Dan's Rock (as mentioned in a preceding paragraph), the

view from St. John's Rock is probably the finest on this trip. W. E. G.

Hitchens, G. G. Townsend, and other public-spirited motorists of

Frostburg, have been principally instrumental in raising the money

necessary to build the road, which leads directly to the rock, around

which there is ample space for leaving or turning cars. About 800 feet

south o f the rock is a low point where the mountain was crossed by

Braddock's Road; an old wood road in fair condition leads to it, and the

distance can either be walked, or a car can be taken over it without

much difficulty.

Just beyond the

side road to St. John's rock, the Pike makes a right curve at 2,880 feet

elevation, almost 1,000 feet above Frostburg: this the actual summit of

Big Savage Mountain, which with Negro Mountain and Keysers Ridge, both

farther along, are the three highest points between Baltimore and

Wheeling. Then there is a gradual descent of the western slope to cross

a stone bridge over Savage River: and a corresponding ascent, this time

up Little Savage Mountain, which is 120 feet lower than Big Savage. One

can easily imagine that the wind blows up strong at times across these

heights; and, looking either ahead or behind, the layman is apt to

wonder that a road of so relatively easy grades could be laid out across

this sort of country.

On the right, immediately beyond Little

Savage; is the farm of Thomas Johnson, a descendent of the first state

governor of Maryland; his house is at the fifteenth mile-post west of

Cumberland or the fourth beyond Frostburg. Nearly opposite, but a trifle

father west, are Mr. Johnson's spacious barns; the larger one shown in

the view on page 51 is at the beginning of the longest straight-away so

far on the Pike west of Cumberland. This was known in stage-coach days

as the "Long Stretch," a continual succession of up and down grades, but

without any deviation from a direct line for two and a half

miles-naturally longer to the freight wagon driver of three-quarters of

a century ago than to the motorist of today. Eight tenths of a mile

beyond the west foot of the Little Savage Mountain, and 65/100 mile

beyond the Johnson house, our route crosses Fishing Run, the first

northward-flowing stream, the waters of which find their way into the

Monongahela, Ohio, the Mississippi and ultimately into the Gulf of

Mexico.

The road could easily have been built somewhat around

rather than straight across some of these ridges, at the same time

securing more uniform and lighter grades; but that would not have been

in keeping with the letter of the law which created the National

Turnpike. One traveling this "long stretch" is reminded of the earlier

part of the trip between Baltimore and Hagerstown, except, of course,

this section is much more hilly. The next few miles are over lesser

ranges and across minor streams, as shown by the map on top of page 48;

and one needs to keep a lookout for the next point of interest, best

identified by a clump of trees on the north side of the road about three

and a half miles from the western foot of Little Savage Mountain. Here

it is still possible to see where and how Braddock's Road crossed the

National Highway; near this point also the third brigade of Braddock's

army camped on June 15, 1755.

Less than a quarter mile west was

the "wagon stand" kept as early as 1830 by John Recknor, beyond which

begins the long descent -- about 260 feet in a mile -- to Two-Mile Run,

a small stream crossed by a short stone culvert. The long "hollow" on

either side of this was once commonly known as the "Shades of Death,"

from the dense forest of white pine which formerly, covered the region,

making a favorable shelter for hostile Indians and shutting out nearly

all of the sunlight even on a bright summer day. Old wagoners who drove

from Baltimore to the Ohio River or beyond dreaded this locality as the

darkest and gloomiest place along the route; and it was the scene of one

or more "hold-ups."

But the once splendid white pine forest in

this part of Garrett County were cut down, sawed up and shipped to

market long ago; so the "Shades of Death" became no more, though it is

only a few years since the last mill made into shingles what was left of

the pine. Many of the larger stumps are still in the ground, and others

were built into the stump fences so characteristic of the once

heavily-wooded country; most of these fences have begun to decay from

their exposure of a generation or more to the elements. About one mile

west the road makes a dip to the small stream known as Red Run, and

immediately thereafter ascends the eastern slope of Meadow Mountain. In

this valley is the small hamlet of Piney Grove, also named from the pine

trees once covering this entire section.

Source: The National Road by Robert Bruce, published about 1916,

pages 31-51.

There are many more maps and photos in the book.

Allegany County MDGenWeb Copyright

Design by Templates in Time

This page was last updated

12/02/2023