|

The Riot of 1930 Sherman, Texas

The

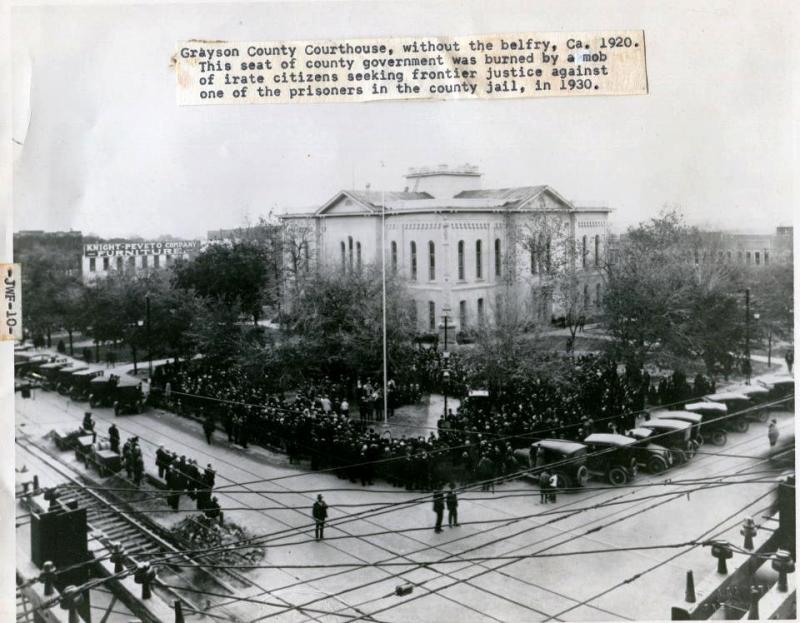

second Grayson County courthouse was burned by a mob on Friday, May 9,

1930 as the sun began to set as the ruins were still smoking, leaving

the stark bare walls of steel vaults still standing in protection of

the irreplaceable records that were housed within their confines.

George

Hughes, a colored man who was from Honey Grove. Fannin County, had been living in

Grayson County for two months and was employed on a farm about five

miles from Sherman on the Luella Road. He knocked at the

back door of a farm house in the morning of May 3 and asked for money

he was owed by the farmer. The farmer's wife told him that

he would be paid when her husband returned from Sherman that afternoon.

Only the farmer's wife and young son were on the farm with the exception of George Hughes. Around ten o'clock Hughes returned, entered the kitchen and forced the farmer's wife into the bedroom. Here he tore her clothing and attacked her. "Ordering her hands in the air, (Hughes) forced her into a bedroom where the alleged assault occurred. Part of her clothing was torn off before she was overcome. Following the assault and with a piece of telephone or electric light cord her hands were bound about her head and tied to a post of the bed and the woman left in that position. "Hughes fled the house, the account said. He went to a nearby barn to search for the woman's young boy who had run from the house during this time. After attacking the woman, George Hughes tied her hands to her neck with an electric cord and then tied the cord to the bed post. Then he tied one of her legs to the floor of the bed and went in search of the child. The boy had run from the house and was crying which caught the attention of some men walking along the road. The men went to the house to investigate. Upon seeing the men, Hughes fired one shot at them and fled toward the Choctaw bottoms. Despite being unarmed, the men followed him. The farmer's wife had managed to free herself and ran to the Taylor farm to get help. Sheriff Arthur Vaughan, upon receiving the message of a disturbance near Luella, sent his deputy, Bart Shipp, to the scene. Two men neighbors walking along the road were alerted by the boy's and the woman's screams, the statement said. Hughes saw them coming and ran into a terraced field near Choctaw Creek. Hughes fired a shot at them, but missed. On May 3, 1930 Grayson County Sheriff Arthur Vaughan was notified that there was a disturbance in the small community of Luella, about 5 miles southeast of Sherman. A request for assistance was sent but as Sheriff Vaughan sent Deputy Sheriff Bart Shipp to the scene to investigate, he was not informed of the nature of the disturbance. When Deputy Sheriff Shipp reached the scene, he was informed that a black man had assaulted a white woman; Shipp was joined by Weldon Taylor in pursuing the suspect by automobile; they cut across the fields in Shipp's car, gaining on Mr. Hughes. While in pursuit, the suspect fired twice at the officers, with shots shattering the car's windshield, riddling its back and top; however, both men in the car were uninjured. Driving the car into pistol range of the suspect, Deputy Shipp ordered the suspect to halt and put up his hands. The suspect obeyed, was disarmed, handcuffed and lodged in the Grayson County jail, where he was interviewed by Grayson County Attorney Joe P. Cox. The suspect was George Hughes and had come to Grayson County from Fannin County. At this time Hughes was formally charged with criminal assault and assault to murder and held over without bond. As the news about the alleged crime a crowd began to gather at the Grayson County Jail on West Houston Street in Sherman. The crowd demanded that Hughes be turned over to them for punishment, but Sheriff Vaughn informed them that Mr. Hughes had been taken to the Dallas jail to await his trial. Not satisfied, Judge Vaughan invited some of the crowd members into the Grayson County Jail to see for themselves that the accused was not there. The jail register for May 1930 shows that an entry was made indicating the placement of George Hughes in the Grayson County jail on May 3 by Deputy Sheriff Bart Shipp and of his release the same day to Deputy Shipp with no reason given. Apparently, based on the jail records, Hughes was returned to Grayson County in the early morning hours of May 9 to face his accusers in the court that convened that day to try him. Judge R.M. Carter called a special venire consisting of 75 Grayson County residents to appear in the 15th District Court at 10 a.m. Monday, May 9 from which a jury of 12 men was chosen. The jurors were: L.A. Hensley, Van Alstyne O.C. Dakey, Van Alstyne G.A. Mehan, Howe F.J. Scoggins, Howe D. Fennell, Denison Fred Sanderson, Gordonville Hunt Smith, Hagerman L.K. Nash, Tom Bean T.P. Roach, Sherman Ernest Orr, Sherman S.B. Boggs, Sherman J.J. Loy, Sherman A special session of the Grand Jury was convened by R.M. Carter, Judge of the 15th District Court to assemble on Monday, May 5; members of the Grand Jury were N.P. Parker, Carl R. Van DeMark, Will Taylor, Max Gibbs, F.J. Wible, J.W. Thompson, W.H. Gilley, S.A. Schott, Paul W. Bean, W.W. Collins and W.J. Hogan, who was appointed as foreman by Judge Carter. The Grand Jury returned an indictment alleging criminal assault and trial was set by County Attorney Cox for Friday, May 9. Sherman Attorney George Hines was appointed by Judge Carter to represent Hughes. The complaint was filed Monday, May 6, in a special session of the 15th state District Court. Four witnesses testified. The county attorney read the victim's statement and another from the suspect. The two accounts coincided. Hughes was charged with three counts of assault and two counts of attempted murder. The crowds outside the Court House grew. A white man who asked to remain anonymous described the scene on Friday morning, May 9, 1930. Only a one-column headline appeared in the Democrat on Sunday, May 4, 1930. On Monday, the story was expanded to two columns. Through Tuesday's, Wednesday's and Thursday's papers there was no mention of the case. On Monday, May 5, 1930, Judge R. M. Carter summoned a special session of the Grand Jury. By 11 o'clock, the Grand Jury turned in two indictments against George Hughes and the trial was set for Friday, May 9th. George Hughes' account of the attack matched the details with that of his victim. There was no question as to his guilt. An editorial in the Democrat said on that day . . . "One of the blackest tragedies ever perpetrated in Grayson county occurred at a farm house five miles south of Sherman, Saturday afternoon. A Negro is held in the Grayson County jail charged with criminal assault on the wife of a prominent farmer." The editorialist continued, "It is fortunate that no Sherman Negro is involved in the crime. The Negro is what is known as a 'floater,' and claims to have come into the county from Honey Grove." Texas Governor Dan Moody sent Ranger Captain Frank Hamer who advised Judge Carter that there would be blood shed if the trial was held in Sherman. Despite the warning, the trial was held in Sherman. Tension had been building in the area. A large crowd gathered around the courthouse on the day that the trial began. Just before noon, the mob leaders tried to enter the courthouse. Only those directly related to the case were allowed inside the courtroom. The rangers occasionally shot into the air in an attempt to control the crowd. Judge R.M. Carter called a special venire consisting of 75 Grayson County residents to appear in the 15th District Court at 10 a.m. Monday, May 9 from which a jury of 12 men was chosen. The jurors were: L.A. Hensley, Van Alstyne O.C. Dakey, Van Alstyne G.A. Mehan, Howe F.J. Scoggins, Howe D. Fennell, Denison Fred Sanderson, Gordonville Hunt Smith, Hagerman L.K. Nash, Tom Bean T.P. Roach, Sherman Ernest Orr, Sherman S.B. Boggs, Sherman J.J. Loy, Sherman The trial began at 10:00 o'clock. However, after hearing only one witness, the crowd outside the Court House became so noisy, angry and violent that the trial had to be stopped. The members of the court, law enforcement officers, including several Texas Rangers, began to discuss a change of venue to move the hearing out of Grayson County because the situation had become too dangerous. At 12:10 pm the jury had been sworn in and Cox read the indictment. G.M. Taylor, the first witness, was called. At 12:20 pm the corridor doors were forced open. Judge Carter sent the jury out of the courtroom because of the disturbance. George Hughes, the defendant, was sent to the vault of the District Clerk, which was the safest place available. In an attempt to control the mob, tear gas was used resulting in great discomfort for those inside the courtroom. After the jurors complained, Judge Carter allowed them to leave by fire ladders put up to the windows. Shortly after noon a woman threw a rock through one of the courthouse windows. Members of the crowd followed her example, breaking out window lights on all sides of the building. At approximately 2:30 pm two teenage boys threw a can of gasoline through a broken window in the southeast corner of the first floor. About 2 p.m. the decision had been made to discontinue the proceedings. The decision came too late as by this time a large can of gasoline had been emptied in the Tax Assessor's office and torched; the flames rapidly spread through the building and the exits were soon blocked by the raging fire.

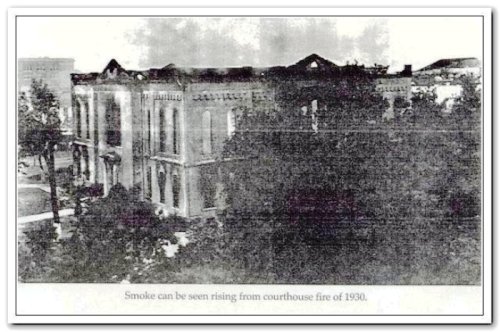

Fire department ladders were quickly set up outside the courtroom windows and the evacuation of the jurors and officers of the court was completed safely. However, the defendant chose to be locked in the vault containing the District Clerk's records rather than face the mob outside which was intent on bringing him to their version of mob justice. The fuel burst into flames which spread rapidly. Judge Carter and Prentice Gafford left the building by fire ladders also. The courthouse was soon a blazing inferno as the rioters would not permit the Sherman Fire Department to pour water on the blaze. Consequently the building was destroyed with the exception of the vaults. During a night of rioting a number of Sherman business houses operated by black people were burned as well. Many of the black citizens fled Sherman for safer places. Meanwhile, Hughes could not be removed from the vault due to the door being closed from the time of the earlier disturbance. It was feared that Hughes would die inside the vault since no one in the building was able to open the vault door. By four o'clock that afternoon, the only things that remained of the courthouse were the walls and the vault. Judge R.M. Carter, realizing the building was ablaze, ordered a change of venue "to prevent bloodshed." The judge, court officers, sheriff, deputies and Rangers found the stairway blocked by fire. Firefighters extended a ladder to the second floor and they escaped. Although accounts vary, Hughes evidently was offered the choice of staying in a sealed steel vault or climbing down the ladder to the waiting mob. He decided to stay and was locked in the room with a bucket of water. It had been impossible for the fire department to extinguish the fire because mob members slashed fire hoses being used. The mob now numbered some four or five thousand. The mob was satisfied by the burning of the courthouse and remained at the scene through the evening, continually attempting to blast a way into the records vault. After some time, a torch was used to burn away the steel wall of the vault. A solid wall of concrete was reveled. Dynamite was used to make an entrance into the vault where Hughes' body was found. It appeared that he had survived the fire but had been killed by the explosion. The crowd still called for Hughes' body which was slid down a fire ladder, hitting the ground with a revolting thud. "That was about 5 p.m.," the drug store clerk said. "The wall had fallen down and had cooled off enough. A man came up with a welding truck and carried a torch up the ladder and cut down through the lock. He walked up there and got that (black man) and said 'Hey I got him!"' Some reports of the time said Hughes was alive when he was pulled from the vault. Others say he suffocated from the intense heat of the fireproof room. The most credible account said Hughes died when shrapnel from the dynamited vault walls flew across the room and struck him in the head. The body was then dragged by a chain which was attached to an automobile to the corner of Branch and Mulberry which was the center of the Negro business district. At this point a pyre was built from contents of a Negro-owned drug store. The body was hanged and burned then turned over to a Negro undertaker. The corner of Mulberry and Branch streets is still ugly - a profusion of railroad tracks, ramshackle buildings and ragweed. Sixty-six years ago the intersection was the scene of Sherman's most horrifying and shameful episode. There the body of George Hughes was sexually mutilated, hung on a tree and burned in a bonfire. Two days earlier Hughes, a 41- year-old black man, had confessed to raping a white woman. Judge R.C. Vaughan, retired from the 15th state District Court, was 14 and in the 9th grade in Denison at the time of the events. "A friend of mine and I actually slipped off in my parents' car to come to Sherman," Vaughan said. "The Court House had pretty much burned then. We managed to get even with the east entrance on Travis Street. The steel vault's shell was apparently intact. "Someone climbed up to the vault and put goggles on and torched the vault. Then an explosion blew a hole in something. The man on the ladder got this defendant's body out and threw it down the ladder. I could see movement in a group of men to the north and west. "Then I was aware that a car was going east on Houston Street. I can't say I saw the body, but people were following the car. We followed the mob on Mulberry. They strung his body on a tree and lit a bonfire. I think I could feel heat and hear flesh sizzle. Someone hollered, "Police!" and we broke and ran. Real Estate records, District, County, Probate, Civil and Criminal records were safe in the vaults; these records dated back to 1846; election records official bond records and all financial ledgers of the County Treasurer and County Auditor were lost. County Auditor I.N. Dickson had prepared the April bills for payment during the days before the fire, together with his report of County fund balances and budget balances, placing them in wire baskets in the Auditor's office for presentation to the Commissioners Court on May 12. Realizing the problems that the county was facing, Mr. Dickson ran to the Auditor's office on the west side of the Court house away from the starting point of the fire and climbed through the window of his office, fighting smoke and heat, gathered up the wire baskets, climbed out of the building to safety, saving the documents and reports that were crucial in importance to the payment of County debts and thus furnishing some financial data that became so important in providing at least a start in setting up new County records. The Comissioners Court met on their regularly scheduled day, Monday, May 12; members of the were: O.L. Simmons, Commissioner, Precinct 1 J.R. Westbrook, Commissioner, Precinct 2 E.C. Winn, Commissioner, Precinct 3 R.L. Rich, Commissioner, Precinct 4 S. Noble, County Judge and Chairman A new Commissioners Court Minutes record, vol. 1, was opened on page 1 and the following was written:

"On Friday, May 9th, A.D., 1930, at the County Court House in the City of Sherman, Grayson County, Texas, one George HUghes, negro, and conffessed rapist, was being tried in the 15th District Court. An angry mob formed on the Court House lawna nd demanded that this negro be turned over to them. At, or about, 2:30 o'clock p.m., this mob set fire to the Court House. The City Fire Department responded promptly to the call but the mob would not permit them to put water on the blaze. The fire hose was cut in several places. Within a short time after the Court House was set on fire, the entire structure was a mass of flames. All Minutes of the Commissioners Court of Grayson County, Texas, as well as all other books and records that were kept in the Commissioners Court, or Auditor's vault, were destroyed. This vault caved in when large iron beams fell across it. The above note is made this the 17th day of May, A.D. 1930 by C.E. Thompson, Deputy County Clerk and Clerk to the Commissioners Court. Signed: C.E. Thompson"

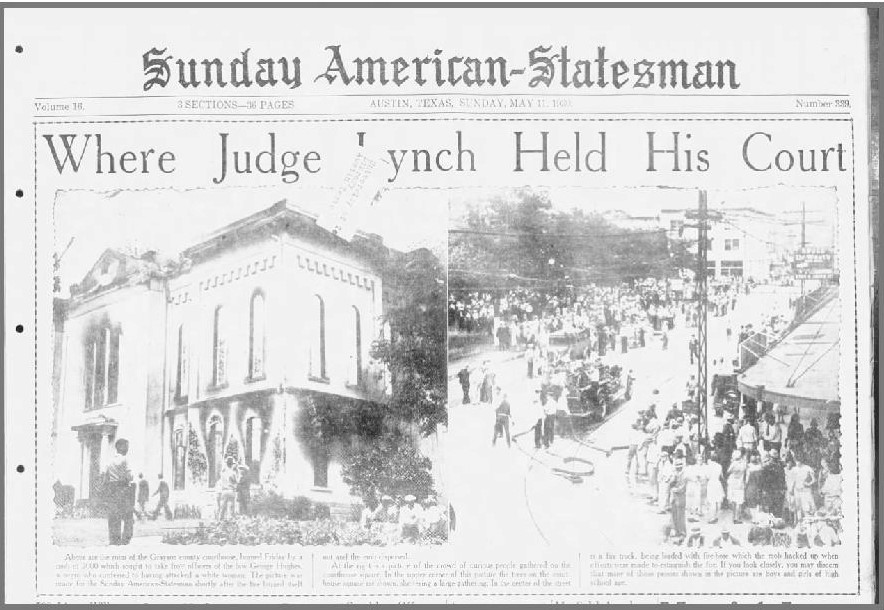

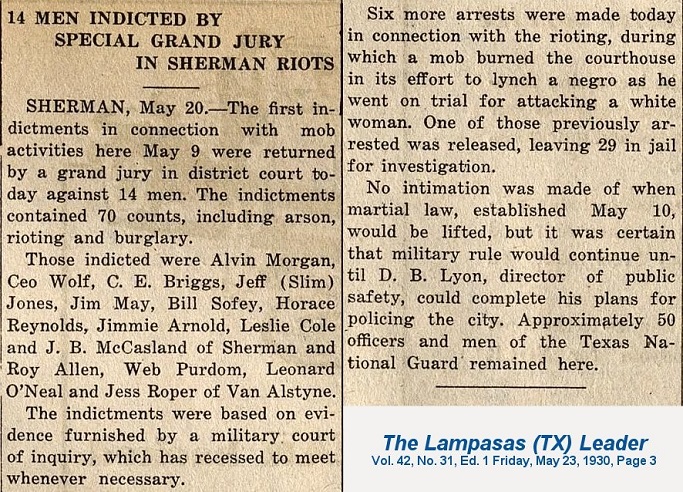

Sunday, May 11, 1930 pg. 1 WHERE JUDGE LYNCH HELD HIS COURT Above are the ruins of the Grayson county courthouse, burned Friday by a mob of 3000 which sought to take from officers of the law George Hughes, a negro who confessed to having attacked a white woman. The picture was made for the Sunday American-Statesman shortly after the fire burned itself out and the mob dispersed. At the right is a picture of the crowd of curious people gathered on the court house square. In the upper right of this picture the trees on the court house square are shown, sheltering a large gathering. In the center of the street is a fire truck being loaded with fire-hose which the mob hauled up when efforts were made to extinguish the fire. If you look closely, you my discern that many of those persons shown in the picture are boys and girls of high school age. Offers of financial help were immediately made by The Merchants and Planters National Bank of Sherman; other business institutions as well as the Grayson County Bar Association loaned or gave such needed items as office furniture, equipment and supplies. Bennett Printing Co. of Dallas, Texas had been the supplier for ledgers, ledger sheets and other books and record forms used by county officials; Mr. Bennett, President and owner, came to Sherman and offered his company's assistance in furnishing any office supplies to begin the replacement of County records; his company still had printing setups in his filed and immediately put his company to work furnishing the required items needed by the County. By May 12, Rangers Frank Hamer, Tom R. Hickman, J.B. Wheatley, J.E. McCoy, J.W. Aldrick, W.H. Kirby, R.T. Goss and M.T. Gonzaullas had left for other assignemtns. Gov. Dan Moody had placed all of Precinct 1, Grayson Co. where Sherman was located under martial law. National Guard troops under the command of Co. L.E. McGee including 377 men and 42 officers were present to enforce the martial law in order to re-establish government and law and order in Grayson County and the city of Sherman. Col. L.S. Davidson was presiding officer over a military court of inquiry set up to collect evidence which would lead to the indictment of people for their connection with the mob violence and rioting of May 9. (Weldon O. Williams. A Journey Through History: Chronological Listing of Public Officials, Grayson Co., Texas, 1846-2000) The event unleashed a great terror among the Negro population. The substantial white population was powerless to stop the mob's actions but they did what they could to assist colored people whom they knew in escaping. Many servants hidden in automobiles and driven to the city limits and placed on interurban cars headed for McKinney, Texas. An elderly Negro woman was protected by admitting her to the hospital. Many Negroes fled along creek bottoms. Several Negro establishments were burned. William Hill also lived in Sherman at the time of the tragedy."I don't know why we never built it (the business district) back up," Hill said in 1990. "I kind of think some of the people never felt like putting their money back into it. I guess they were scared that the climate was bad and they could lose it all again." Andrews was probably the most qualified to rebuild, but he had been killed two years before. His family just never seemed interested." Hill said the gap in services was filled by white practitioners. "Many went to white doctors and dentist," Hill said. "You could shop in grocery stores and clothing stores as long as you had money. There never was any discrimination in spending money." The tragedy of May 9, 1930 extended far beyond the initial crimes. Alexander Bate, while talking about the 1930 tragedy, lamented the loss of the black business district. Many of the black citizens fled Sherman for safer places. Sherman's black community, he said, was just never the same. However, he said, although blacks lost a lot to an angry mob, many white people extended their hands in genuine friendship. The enraged mob destroyed the thriving three block black business district. The fuel to fire Hughes' funeral pyre was gathered from the ruins. Sherman's black community has never regained the wherewithal to rebuild. In 1930 most black businesses here were located in the two-story, brick Andrews Building in the 200 block of East Mulberry. The building was owned by a successful black farmer from Bells. A.J. Lawrence owned a grocery store, E.M. Barrier was a shoemaker, N.S. Everett & Brother was a transfer company. The Andrews Theater was next door to Walker & Tellies and J.A. Sims, tailors. Mrs. Hollie Robinson's Restaurant was down the way. Fraternal Funeral Home was in the Andrews Building as was a dance hall. J.D. Godson had a drugstore downstairs from brother Samuel Godson's doctor's office. Blanche Crows put her dressmaking shop next to R.L. Crows' tailor shop. J.P. Hampton had his shoemaker shop in the same building as did J.E. Richardson. The Williams Hotel sat just across the street. Sherman's black population had its own Odd Fellows, Knights of Pythias and Masonic Lodge. Many black professionals made their way to Sherman. Dr. R.L. Staghound and another black dentist practiced here. A funeral home competed with Fraternal. Blacks practiced law and engineering in the town. There was also another black physician. Alexander Bate, a retired science teacher and coach, was 22 years old the night George Hughes' body was dragged through East Sherman and burned. Bate and his wife Peaches, lived only three doors down from his family home on Montgomery Street. In 1930, he witnessed the tragedy from his roof top. The following is his account, given in 1990. "Oh, yes, I saw it. They set that (Andrews) building on fire. I got up on top of my house with a bucket of water. There were big old sparks raining down from the fire. Just about every-body in the 600 block of Montgomery left. They were just scared to death. Now my mother had her leg amputated and she didn't have her wooden leg yet. We didn't have any trans-portation. My Dad said, 'Son, we'll have to stay here.' He gave me the shotgun and I took it back up on the roof. I only had five shells for it. But he had a .32-20 pistol and a whole box of shells. He walked from our house down to the Masonic Lodge and some old guys came out with 2 gallons of gas and were going to burn down the Masonic Lodge. He drew down with that .32-20 and they got out of there so fast, I believe they just about broke every spring in that old car of theirs trying to get away from my papa. Late that night, they were working on the Court House with dynamite, trying to get him (George Hughes) out of there. They drug him right down this street (Crockett). It was the most disgusting thing I have ever seen. "A lot of people kept hogs in town in those days and the black people went and hid in the hog pens for safety. The people were afraid. They went to stay with their families in other towns and with the white people they worked for. I worked for the Marks Brothers and they told me I could bring papa and mama out to stay with them, but by then things were getting better, so we stayed. The Governor of Texas placed the city under martial law until complete order was restored. Order came although the incident was still a popular topic of discussion. Some people are still sensitive about it. Names of people indicted in weeks to follow were carefully left out of the newspaper files in the public library. "Then the governor, who was one of the most popular governors ever, sent in the troops and said don't shed no blood. A militia company arrived from Dallas but was driven from the city street by the mob over whom they had no authority. Two teenagers and four troopers were wounded. The troops retreated to the old jail and set up pickets around the door and on the roof. They came and the rain came and everything cooled down." The mob required a considerable amount of cooling down. Its temper had simmered for five days, fueled by newspaper accounts of the crimes. The event of Hughes trial attracted a crowd of more than 5,000 people from all over North Texas and southern Oklahoma. Eventually two Texas National Guard units and at least three Texas Rangers were dispatched by Moody. Dallas Morning News 13 May 1930 Military Court Is Conducting Rioting Probe Findings Are to Be Presented to Grand Jury at Sherman By Walter C. Honaday, Staff Correspondent of The News Sherman, Texas, May 12 -- The long arm of martial law reached out Monday to bring in more suspects in the recent rioting and to gather much important information from witnesses as the military court of inquiry went into action in the effort to fix guilt for the mob violence of last Friday and early Saturday. Sherman citizens responded readily to the call for co-operation in rounding up the leaders in the burning of the courthouse and the other events of the reign of horror. Col. L.S. Davidson, provost marshal and presiding officer of the court, said Monday afternoon after the first day's sitting. Good progress was made and sufficient evidence gathered to give the guardsmen and rangers an opportunity to make further arrests. Ten witnesses were examined, including several prominent Sherman citizens who appeared voluntarily.

Of the 39 men eventually arrested for the riot, arson and attempted murder, 10 were from Sherman and 4 were from Van Alstyne. Fourteen were indicted, but local newspapers of the time have been robbed of information about where those indicted lived. The only editions remaining on file at the Sherman Democrat were mutilated long ago. Sherman and Grayson County are ashamed of that weekend. The Democrat published "Sherman's name has been dishonored by the people of her own county. It will take a generation to outlive the stain on her honor, if it can ever be done." Sources: An Illustrated History of Grayson County, Texas by Graham Landrum, 1960, pg92-94 "Angry Mob Rules in May 1930; Courthouse Burning Remembered." Sherman Democrat, Sunday, March 17, 1996, section 2, pg.11 Weldon O. Williams. A Journey Through History: Chronological Listing of Public Officials, Grayson Co., Texas, 1846-2000 Statement from Frank Hamer, May 13, 1930 Proclamation of Marshal Law in Sherman, May 10, 1930 George Hughes Sherman History Copyright © 2025, TXGenWeb. If you find any of Grayson County, TXGenWeb links inoperable, please send me a message. |